In August 2017, my husband, Josh, and I traveled to South Carolina to see a total solar eclipse for the first time. Filled with wonder and awe at the ghostly halo of our sun’s corona, we became eclipse chasers. In 2019, we witnessed this astronomical event in Chile’s Elqui Valley. And this year, on April 8, when a total solar eclipse crossed North America from Mexico to Canada, I was in the path of totality once more, this time in Texas. Alas, it will be 20 years until I’ll have the chance to witness a total eclipse again, at least in the contiguous United States. (Planning for Spain 2026 is underway.)

When I try to explain what it is like to watch a total solar eclipse, I often refer to Annie Dillard’s famous line: “Seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane.” Most people who have seen an eclipse have encountered a partial. Totality is something on another order. During a total eclipse, when the moon crosses in front of the sun, the two bodies appear to be the same size. That’s because the moon is both 400 times closer to us than the sun and 400 times smaller. As the moon ever so precisely blocks the sun’s visible light from our view, everything goes dark and cool here on Earth. But that isn’t the most amazing part. In a total solar eclipse, you can see the sun’s corona—its outer atmosphere—which normally isn’t visible because the sun’s surface is so much brighter. As soon as the moon blocks the sun, the bright white corona pops into view. In a partial eclipse, the sun is never completely blocked, and you never see the corona. Even in an annular eclipse—when the moon is farther away at the time of the crossing—too much sun comes through for the corona to be visible.

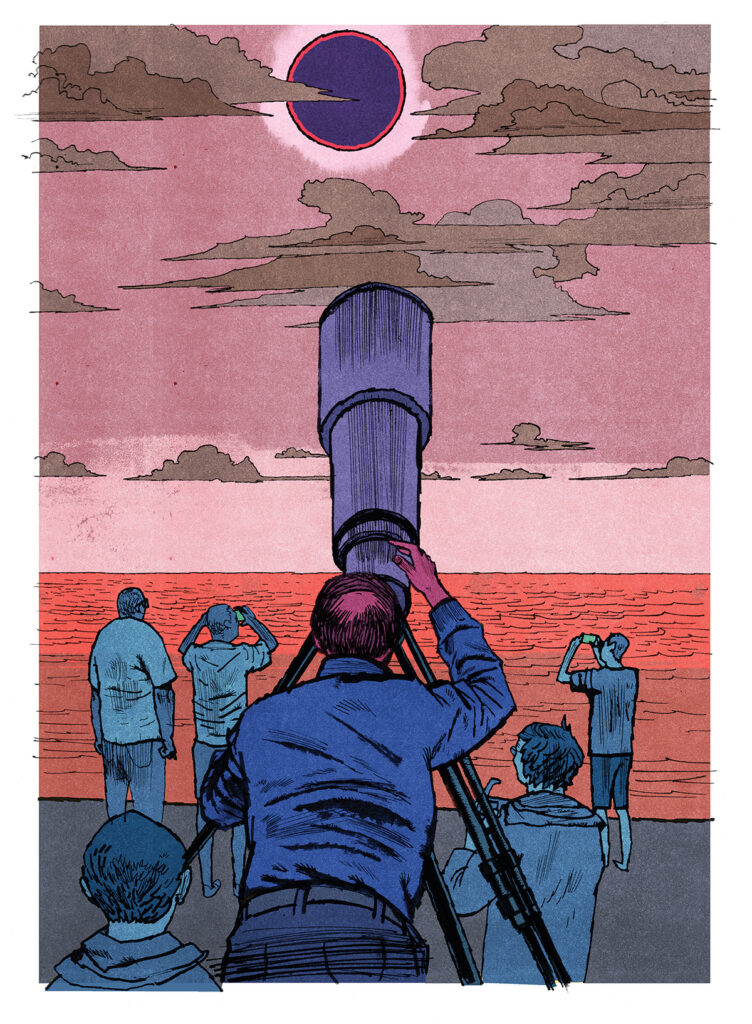

Josh is a NASA engineer, and both of us are space nerds. Back when we were dating, I bought him a Dobsonian telescope—a large-aperture reflector—which we often took with us on stargazing weekend getaways. (Friends of ours who wanted to join us had to drive to the destination separately; the telescope took up the whole back seat of my car.) We knew that we wanted to see the August 2017 eclipse, the first in a century to pass across the United States from coast to coast, leaving the country by way of Charleston. When I got a job doing public outreach for NASA, our journey became a work trip. I was given the task of broadcasting the astronomical event from the rooftop of Fort Moultrie, located in Charleston Harbor. We would be bringing the eclipse to the world using our own telescope and homemade sun filter (without which the sun’s intense light, focused into the small opening of an eyepiece, would fry the viewer’s retina).

On a hot August day, we packed our telescope into a rented minivan and drove from our home in Virginia to South Carolina. Our hotel, about 10 miles outside Charleston, was packed with members of the media and amateur enthusiasts. We saw cameras everywhere: under coffee tables, in elevators, in the hands of white-haired men in unbuttoned Hawaiian shirts. Cities located along the path of totality—from Salem, Oregon, to Jackson, Wyoming, to Nashville, Tennessee—had been preparing for massive crowds, and in South Carolina alone, an estimated 1.6 million people had come to witness totality.

The morning of the eclipse, we woke up early, met the three other members of my team in the hotel lobby, loaded our equipment into vans, and drove south. The roads were eerily quiet, a state of affairs very much at odds with the large flashing signs warning motorists about expected heavy traffic. The forecast for Charleston, it turned out, had called for mostly cloudy skies with a chance of scattered thunderstorms—hardly the optimal conditions for seeing an eclipse. And so, many people had headed farther inland, where the weather was supposed to be better. Now, as we drove toward Fort Moultrie, Josh hardly spoke: he would have surely joined that inland exodus had he not agreed to talk about the eclipse on our live broadcast.

We arrived at the fort (which is part of the Fort Sumter National Monument and is administered by the National Park Service) and made our way up to the rooftop. At eight in the morning, the air was oppressive and wet, and we used paper towels to dry the sweat from under our shirts. Because I was supposed to be on camera, I’d decided to wear makeup, which was now smearing in the heat. A group of students from the College of Charleston boarded a Coast Guard boat to travel a few miles offshore, where they would launch a weather balloon into the stratosphere. Some of my colleagues went along to film them. Meanwhile, other students from the college joined us on the rooftop; they would watch the eclipse and record data transmitted by the balloon. All of us began to worry, however, that there would be nothing to see. The sky was one big continuous cloud, with flashes of lightning in the distance, and a Park Service official warned us that the rooftop would be evacuated if the lightning came any closer. When we started our show, we noted the conditions, feigning excitement about how people in other locations along the eclipse’s path would be treated to a magnificent view.

Wearing a cowboy hat, his NASA polo shirt tucked into his jeans, Josh pointed our Dobsonian reflector at the clouds. Without a clear view of the sun, however, we weren’t able to frame the telescope to test the feed and ensure that the exposure was correct—on the off chance that we would see the eclipse. We rolled through our broadcast program in a formulaic manner. Interview the ground crew. Interview a Park Service representative. Pretend to be excited—even though all we could think about was how we might miss the event. The partial eclipse had started, but we hardly knew it. No need to don any protective glasses (necessary for a partial but not a total eclipse): there was barely any sun to block. During a brief break in our program, I headed to one of the rooftop overlooks. I looked out over the water, then down at my notecards, preparing for the next segment, rereading the script I had studied a thousand times. That’s when I heard people shouting on the other side of the roof. The clouds were parting, and the moon was slowly crossing in front of the sun.

We were three minutes away from going live again, and now that the sun was out, we had a chance of actually capturing the eclipse. The clouds were still intermittent, so Josh was finding it hard to frame up the telescope on the sun. He scanned across the sky, pointing it where the sun was supposed to be, but the camera’s viewfinder was still just black.

“It’s not going to work,” he said.

“It has to work,” I said frantically. “It’s our only option.” We knew that without the telescope, we’d having nothing to show during totality. We’d be back on the air in less than a minute, and we wanted a view of the corona.

I opened the aperture, lowered the shutter speed, and raised the light sensitivity. Josh moved the telescope around, trying to point it directly at the sun. And suddenly, there it was. The sun was almost gone, and a black circle was closing in on it. The color changed so quickly that we almost didn’t notice until dusk hung all around us, tinted with a shade of yellow. Everyone’s faces looked like a dream, gray with a golden hue, as if all of us were characters in a very old movie.

“Oh my word!” the boy next to us shouted. He was a junior ranger I had interviewed earlier.

We all shouted to no one and everyone all at once: “Yes! Wow!” It was as if we had all lost control of our voices, experiencing and expressing emotions we would not normally share with strangers.

“The corona! Totality!” we chanted, though our stream was not picking up our voices; it was only transmitting the telescope’s feed.

“There they are—Baily’s Beads!” Josh shouted with the enthusiasm of a child. He was referring to the last flash of sunlight right on the edge, illuminating the crevasses and textures of the moon’s mountains and valleys. And then, the sun was gone. The corona came out with aplomb: the final event, right on time, a gorgeous white web emanating from a black velvet moon, jellyfish tentacles flowing outward—tentacles that had been there all along yet were hidden from us until now. We cheered as if we were part of a large crowd at a rock concert, say, or a football game. As we stood on the roof of that fort, dripping with sweat, our perception of the sun changed completely when that white lion’s mane burst forth from the huge ball of hydrogen and helium we’d always known, extending into the corona and then out and out, touching everything in our solar system. The perfect circle, typically the only visible part of the sun, was not visible during the eclipse.

One minute and 36 seconds after it began, the total eclipse was over. The sun came back out, and the eclipse was a partial, meaning that we had to don safety glasses to view it. And there we were, on a rooftop with people we would never see again, but whose voices would make us cry when we’d later watch the video, over and over again, trying to relive the experience. We had witnessed the opening of a portal to the sacred, an experience that we will never forget, one shared with total strangers. We had all been indoctrinated into the cult of the corona.