In the Mushroom

True foraging isn’t the domain of the weekend warrior; it’s serious, serious business

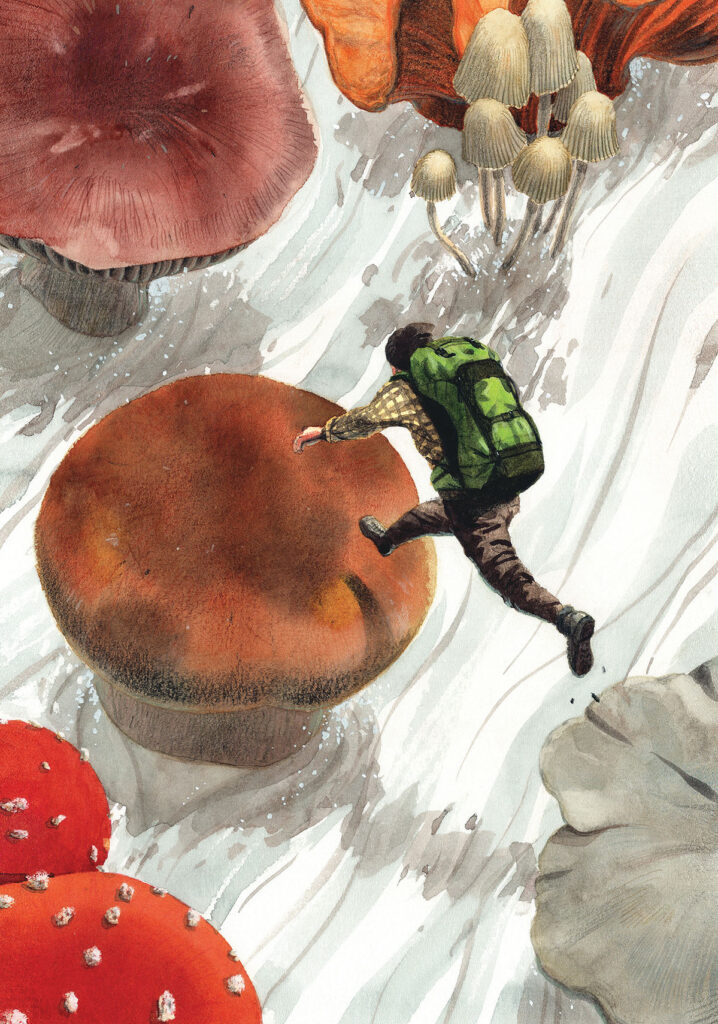

To forage is to look for things that aren’t lost. Birding, mushrooming, hunting agates in the wet sand at ebb tide or arrowheads in the sagebrush along the edge of a dry playa—everything I’ve spent time seeking has been right where it belonged, indifferent to whether it was found. If I failed to see birds when I could hear them or gather mushrooms when I could smell them, I considered it a failure to live in the right relation to my senses. The most apt phrase I know for the necessary state of attunement comes from psychoanalysis. The analyst, in Freud’s idealized therapeutic environment, cultivates “evenly hovering attention”—hard to cultivate, harder to maintain, no matter how early one starts.

I was introduced to foraging early, not long after I could walk. My great-aunt Jara would take me by the hand, and as we ambled, she pointed at each mushroom we came across, mixing nicknames and Latin names: Russula, cep, amanita, slippery jack. My mother’s family came to the United States as refugees from what was then Czechoslovakia. As in so much of Eastern Europe, mushrooming is cultural, the people mycophilic. From one family trip to the beach, I remember stumbling on a big “king” bolete, Boletus edulis, just feet from the driveway. There was something unnerving about it, every day fuller, rounder (yes, they can be phallic). I lay in my little trundle bed and wondered at its swelling. When my parents separated, we stopped visiting the beach as a family, and for perhaps 25 years I didn’t think of mushrooms except on holidays, when I saw my great-aunt, a shy person who had given me a gift I never thanked her for. But then, on a hike with a friend at Oregon’s Fort Stevens State Park, I felt my way back into the pleasures of this kind of attention, mist beading on the smooth caps of boletes, Russulas, and slippery jacks and pooling in the shallow, wrinkled cups of the lobster mushrooms, named for the red color of the cooked crustacean. I had discovered again something I could do for pleasure and distraction, and distraction was what I was always seeking.

For as long as I’ve lived a conscious life, no matter where I am, even in my own bed, I have been nagged by the feeling that I don’t belong, as if I have no right to be anywhere. A trespasser in my own life, living from one period of absorption to the next. Most of these distractions have been idle, for pleasure; the failures to find what I sought were not losses. Mushrooming, however, I did for money. Was it the fall of 2007? Or 2008? It was a painful period, the details hazy. Since 2000, my father had been ill with his second cancer, and though it was a cancer he could, according to the oncologist, “live with and not die from,” my old man felt so much self-pity, flirting with Oregon’s assisted suicide law, that he was nearly impossible to help and impossible to pity. And around the same time, I had given up painting, the thing I loved doing most: gave away the finished works and took the unfinished ones to the dump, cleaned the studio, folded the easels, boxed up the paints and brushes. I didn’t like who I was when I painted, but it still throbs like a phantom limb, that life I gave up. I was on the verge of losing the few friends I had. Most of my old friends had partners and children, while I had neither, and had kept the wild habits from our bachelor days. Now I was the guy eating dinner alone at the bar, eavesdropping. Having never thought I’d see 30, I spent whatever money I had. That autumn, again without a job but still in possession of a car, I remembered the mushrooms, and headed out of Portland on Highway 26.

I’d been at it more than a week, almost a hundred hours of driving, stopping, bushwhacking, driving again, when late one frustrating day, already miles farther from the city than I had hoped to go, I braked hard to take a sharp right and rolled on rough pavement along the Necanicum River with the windows down. The sweet smell of rotting porcini is penetrating and unforgettable. Is it, as the connoisseurs say, the smell of fine old Bordeaux or Burgundy? Old wine might deserve the epithet “mushroomy,” but deliquescing porcini have a fresh, piquant stink. I pulled onto the shoulder, the smell overpowering, and got out. Where pavement met gravel, I found it: a rotten Boletus edulis, fat, soft stem within an inch of the macadam, and another perhaps three feet away, both stuck with the leaves blown off nearby trees that were giving up, their growing season over.

Two days later, I left home before dawn, drove straight to this spot, and scouted by headlamp but found little. Paths worn in the duff. That little patch of ground next to the fast-flowing river had been walked many times over the years. Yet among the roots of tall, scaly-barked western hemlocks were four to five pounds of fresh chanterelles, and another couple of pounds with dry brown edges. Though I found no fresh ones, those rotting porcini were the great prize, promising riches. Back on the highway, I hadn’t gone far when I passed a graveled shoulder wide enough to park two cars. Across the highway, the flattish ground was littered with old trunks and shaded by tall hemlocks. It looked like old logging slash that nature had reclaimed. Yet I couldn’t be sure it wasn’t a so-called beauty corridor—a euphemism for a strip of unlogged timber, to preserve the impression of unspoiled forest for the tourists, with the land beyond clearcut—or whether this might be a grove of mature trees home to fruiting mycelia. I turned around, drove back, turned around again, and parked.

Despite knowing better, I like to imagine that mushrooms flower like trees (I recognize this is plant-centric thinking). Although mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of a dense tangle of mycelia, they are composed, miraculously, of just one kind of cell. As biologist Merlin Sheldrake observes in Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds,

Imagine bunches of grapes growing out of the ground in their place. Then imagine the vine that produced them, twisting and branching below the surface of the soil. Grapes and woody grapevines are made of different types of cell. Cut up a mushroom and you’ll see that it is made of the same type of cell as mycelium: hyphae.

In the woods, to harvest these earthy, earthed fruits, I picture a tree growing underground, the fruit emerging over days or weeks, the season over in a couple of months. A good “tree” will fruit regularly throughout the season. Find an “orchard,” and you’ll have more mushrooms than you know what to do with. And an orchard was what I needed.

Pennybun to the British, Steinpilz to the Germans, porcino to the Italians, and cèpe to the French—whatever one calls Boletus edulis, the king of the boletes prefers certain trees. I found my orchard in a stand of mature, second-growth western hemlock. Porcini associate with other conifers, too, and with birch and aspen. But mushrooms surprise; cep is cunning. A few years later, after the hemlocks hosting my orchard had been clearcut, I accepted a gift from a forager who was retiring. He’d just had a child, and his wife wanted him near. He wanted his perfect spot to go to a good home, like a beloved pet. And it was pretty miraculous; some days I pulled more than 100 pounds of porcini from that place. Yet I would never have looked there had I not been tipped off because the terrain was all wrong.

I always give away the first big day’s take, biblical first fruits, but will not tell even my own mother where I pick what I share with her. We joke that I’d have to kill her if I told her. But for some, this is no joke. Mushroomers stay out of one another’s way, out of both suspicion and respect. Though I know of their existence, and have driven by them, I would never sell to the mushroom camps where wholesalers set up in wait. Over the years, when I’ve sighted other foragers, I might raise a hand in greeting. But only if they have spotted me; and I would never, ever approach them. Once, two guys hurried up to me in a parking lot and stopped me abruptly, too close, asking all sorts of questions. I had just closed the trunk of my car on maybe a hundred pounds of porcini and lobster mushrooms. The men were tactless amateurs, clearly lacking respect for the mushrooms, and for me. I uhmed and ahed and admired the tips of my muddy boots.

Weekend warriors make a day of it, bring the dog, take photos and videos. I never mushroomed on weekends. I tried to professionalize, knowing full well that foraging is a business of feast or famine, at the edge of legitimacy. Every mushroomer remembers epic years when you couldn’t walk in the woods without kicking chanterelles, matsutakes, porcini—all the choice edibles. One year, chanterelles were so abundant in the Cascades, a guy parked a battered pickup on Hawthorne

Boulevard just west of the movie theater, the truck bed loaded with five-gallon buckets overflowing with chanterelles, and sold full buckets for $10. That year the bottom fell out of the gourmet mushroom market. By contrast, good product early in every season commands a high price. In the fall of 2022, a gourmet grocery in Portland was advertising “local” chanterelles for $99 per pound. My mother asked around, learned chanterelles weren’t fruiting yet, went back to the store, and confronted an employee, who admitted that the “local” chanterelles were from China.

For years I’d worked in restaurants, from mom-and-pop Italian joints with candle stubs in wax-crusted fiaschi to fine-dining places where every front-of-house employee had a daily quota of starched linen to fold in elegant isosceles. I’d been a bartender, manager, waiter, sommelier; catered big weddings under tents that cost more than my year’s wages just to erect; and worked small private parties with $20,000 of fine wine on the table, the meals prepared by chefs who went on to work at the White House. But even when I served in a now-defunct Michelin two-star in a hotel just off Chicago’s Magnificent Mile, somehow the foragers in their wet wool coats, types straight out of central casting, got in the door and up the service elevator to the kitchen, with mushrooms, ramps, and heirloom vegetables.

If there are product standards, they likely vary state by state. In my experience, porcini are designated #1s or #2s. The most prized are small, under six ounces, though occasionally you land a big #1—but mushroomers tell as many fish stories as anglers and are not to be trusted. The fruit of #1s must be dense, with flesh of cap and stem white, and if the cap has begun to detach from the stem, the cap’s underside must be white, too. In the field, for me the test of a #1 is whether, as I trim it, the blade squeaks as it passes through the firm flesh. #2 is a far wider category, a catch-all designation: the flesh softer and starting to color; the cap thicker, nibbled by slugs, deer, squirrels, and often pricked with tiny pores where flies have laid their eggs. Sometimes the difference between #1s and #2s is a downpour or a dry spell. Drenched in a heavy rain, porcini get spongy; in dry weather, the tubular basidia on the underside of the cap begin to yellow. Mushrooms start to age as soon as they come out of the ground. After a day in the backpack and the car trunk and a night in the fridge, some #1s don’t look as good as they did when, elated, I held them up to the sun as if they were gems I could admire with a loupe.

Unlike truffles or ginseng, porcini sell by the pound (at least that’s how I wholesaled them). But what one chef considers #1s and is willing to pay $12 to $15 a pound for, another will soft-sell: “Nah, those aren’t fresh enough, those #2s, I’ll give you $8 a pound for ’em.” I was fortunate, connected. I had steady customers, and by the end of the season, at least two places would take whatever I brought them, and paid well because my product was very clean. For a season, I was a trusted source, which is why I refunded the cost of a whole delivery when a batch of #2s turned out to be riddled with fly larvae, probably because the restaurant let the mushrooms sit for too long in the walk-in. Whatever the case, the chef was pissed; I had ruined her menu. Another time, I was passing by a different restaurant when the chef, a friend of mine, saw me and came out to ask me to break some bad news to a few of his regulars. They’d taken a guidebook into the woods, brought back a box of mushrooms they’d found, and asked my friend to cook them. He’d wisely demurred. They had several varieties. A few were edible, two types would have made them sick, and one might well have killed them. It’s not like birdwatching. You can’t learn to mushroom from a book, not unless you have excellent health insurance, or are willing to play chicken with your future.

How to look takes practice. As the saying goes, one learns to get one’s eyes on, to notice telltale disturbances in the duff, the shine of a sticky cap stuck with freshly fallen leaves, the unmistakable silhouette at the edge of a clearing or a clearcut. Seeing a bolete, I uncover the cap and reach down: the shape, size, texture, and firmness of the stem confirm whether this is cep or another, less desirable variety of that large family (about 300 are found in North America). A common saying: “Amanita is friends with cep.” I mean the fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, famous for its “blood-red cap with pyramidal, white patches.” Gary Lincoff, author of The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms, explains: “This mushroom is called the Fly Agaric because it has been used, mixed in milk, to stupefy houseflies. The Fly Agarics of North America cause delirium, raving and profuse sweating. Unlike its Siberian relative, this induces no visions.” I’m sure there are psychonauts whose experiments with hallucinogens contradict Lincoff. In fact, I once met one at a party and didn’t believe a word he said. But in the woods, coming upon a cluster of amanita, I get down on my belly to look under seedlings, wade into nearby thickets, anything to clap eyes on amanita’s edible friends.

That stretch of land across Route 26 proved fruitful, but it was too close to the highway. Mushroomers had worked it, were working it regularly. Scattered about were the white poker chip–size bits sliced off the stems of fresh porcini. Some folks just twist or snap the porcini off at the ground, leaving an off-white stump, unseemly and surreal, like a yeti’s molar. I prefer to reach in along the stem and pop it off at the base, where it is often the pale yellow of a hard-boiled egg yolk. Superstitious, and eager to leave no trace, I push my trimmings back into the hole I uncorked the mushroom from, and brush duff over the spot.

Working my way along the shoulder that first day, taking a few #2s as I went, I took stock of where I was. The ground rose to meet the long sweeping curve of a logging road. I followed the gravel back to the gate with the sign warning against trespassing. And on this sign, fine print explained that one can acquire a permit to forage there. At the outset of my quest, I’d visited offices of the Weyerhaeuser logging company—I think it was in Seaside—to apply for this mythical permit. The woman I spoke to couldn’t believe I was there asking. I took her incredulity as an indication that no one actually heeded the company’s legalese, no one came all this way to ask. No one but me. In tens of thousands of acres, did I really think I’d get caught? Only once that fall did I come upon company employees, surprised two of them at the bottom of a steep, short rise. Dressed in work clothes and hi-viz safety vests, one asked, anxious: “Do you have a gun?” “No,” I replied. Instantly they lost interest, went back to doing what they were doing, surveying I think, maybe laying out a road for next year’s cuts. The rest of the time I worked over that ridge, I saw just two other people: a log truck driver I spoke with for a while—he was lonely, and I lent an ear—and another mushroomer I found myself following. Walking up the hill, he trimmed porcini with a bowie knife as he went. Porcini that would have been mine had I arrived five minutes earlier. I tailed him for the better part of an hour, never letting on that I was behind him. It was the end of the season, he might have been picking the last of them, and I was jealous: those porcini were mine! But I had slept in, arrived late, and lost out.

There for the first time, however, not knowing who might be about, I skirted the curving gravel shoulder of the road, staying out of sight, before deciding, finally, to risk it. The climb was steep, and the farther I ventured in, the less likely the ground was to have been picked over. I wanted ground untouched by other mushroomers, and that’s what I found where the road leveled out, maybe a mile from the highway and up what felt like a thousand feet. The view was fine. To the west I could just make out a few buildings in the blur of waterlogged sea-light. To the east, the taller peaks of the eroded coast range, and through the trees a strip of Route 26. Not out of earshot of the farting exhaust brakes of trucks making the steep descent east of where I’d parked, I would not get lost, as I had been once on Mount Adams, even if I worked into the night.

At the top of the ridge, my logging road—I was already thinking of it as mine—turned sharply west, along a steep road cut. A wonderful feeling, to locate what I had been looking for, and to be catching my breath after hiking without pause. The smell was strong, and there, right at the highest point of the road, the cap like a flag on the tall stem, was the unmistakable silhouette of a porcino. (The singular, porcino, is rarely used in English, and never in the mushroom trade—elsewhere I use the plural, whether I’m speaking of one mushroom or many.) Where the road cut ended, old parallel tracks picked up, with chanterelles spaced along the ruts like landing lights on a runway.

Memory has perfected this welcoming wood, assembled and organized the incidental, collapsed the impressions of several days into a single, stable composite. Another condition distinguishing me from the weekend warriors: I was going into the woods to make not memories but money. Which is why, after I decided I had better use my mushrooming skills if I didn’t want to risk eviction, I applied for that permit. I would feel better if I had some kind of permission, confirmation, certification, some proof that I was not wasting another stretch of a life mostly wasted.

Mushrooming is a lonely job, but I never minded working alone, and it offered a priceless commodity: sound sleep. Coming home exhausted from the woods after dark, hanging on the steering wheel for the straight 15-mile stretch after the cutoff for Banks, I witnessed, in time lapse, the development of my hometown of Portland. Inbound, I drove east past empty fields waiting for their warehouses, low-rise corporate buildings with wraparound reflective windows, cheap townhouses, parking lots, sports bars, big-box stores, and the new Krispy Kreme where the sugar-high staff gave me free doughnuts whenever I stopped. Eyes on the road now, the traffic knotting up, headlights-to-brakelights, at the 217 interchange, St. Vincent hospital on the left. Home, I cleaned mushrooms for a few hours, went to bed, slept hard, like a thing dropped, and woke with a start, late. With my product, I made the rounds of the restaurants, often staying for an early dinner at the last place I made a sale. To bed early in order to rise before dawn and light out for the woods, seeing the city dwindle in the high beams.

That day in the forest, I didn’t immediately answer the call of those inviting chanterelle landing lights, but climbed along the edge of the slope to take down that porcini flag. It was old, not a keeper. But they were growing here. I had only to get my eyes on, look. A warm day in mid-October, the sun shining where I walked, crouched, and pushed aside leaves and twigs, finding small, fat, firm #1s, not yet open, and big #2s, the thick caps with irregular curves like floppy slouch hats, the undersides butter-yellow, a few fly larvae inching across the slimy brown tops. Some of these were #2s, still worth taking, just brush off the larvae; some were #3s, which I might have taken if I didn’t have to lug them so far down the mountain to the car. Even sticky, wormy porcini are good for drying. For much of that fall, no matter how much I scrubbed, the tips of my fingers were stained brown from handling so many mushrooms.

I worked my way along the edge of the road cut, back down to the track that led into my woods. I found a spot close to but out of sight of the road, not in full sun but not out of it, and sat, back against an old log, to eat lunch. Always the same lunch, which was just more of the same breakfast I ate while driving out from Portland at four a.m.—eggs scrambled with onions and cheese in a flour tortilla, maybe a dollop of salsa if I had any, the whole thing wrapped in foil; a couple of party-size bags of Kettle chips, one usually open inside my coat; bars of dark chocolate; the occasional apple.

My big mountaineering backpack was about half full. Another productive hour and I’d have to haul my load down to the car. There was coffee in the car. I was drowsy. The thought of coffee made me wonder whether I shouldn’t do the lazy thing and descend now, just for the pleasure of drinking it. I knew my search for an orchard was over. I had my living, and I’d be coming back here for the rest of the season. (And I did: those slopes produced 25 to 40 pounds of chanterelles and 15 to 30 pounds of porcini, Monday, Wednesday, Friday, for almost seven weeks.)

Instead of descending, I dozed. Had a breeze in the canopy of the hemlocks woken me? I’d slept soundly, for how long I don’t know, but not long. I’ve never worn a watch and didn’t have a cellphone. No one knew where I was, and that’s how I liked it. I guessed it was almost 11 o’clock. I figured, talking quietly to myself, hoping the mushrooms might overhear: I’m alone here, I can leave my backpack behind the log, and look around. I went back to the edge of the gravel. There was one patch to survey before I’d follow those inviting tracks into the trees.

Here I came upon a depression, maybe 15 feet across and three to four feet deep at the deepest point, steeper on one side than the other and evenly coated with pine needles. Needles had been collecting in this hollow for years. Everywhere I put my hand or foot was pillow soft, and right at the lowest point, the telltale bulge in the duff: a mushroom there, a porcini. I’d seen big ones before, caps more than a foot in diameter and inches thick, stem as thick as the thick part of my calf. But this was something else. I brushed away the damp loam. The ground was moist—maybe water collected here. Maybe this baby, huge and pale, was saturated. I couldn’t believe the extent of it, the mass; or the color of the cap, which appeared to envelop the stem: gray, almost the lavender of a fresh #1, as if it had grown enormous without maturing.

I slipped my hand under the moist lip of the cap and reached in and down until I felt the stem. I could not encompass it with one hand. I crouched over it with my knees spread wide, and slipped a hand under either side of the cap and reached down, down. I was at the depth of my elbows and was still not sure I had reached the stem’s widest point. In an impossible position, I extracted my slimed arms and moved to one side, to reach underneath it and lift it like a box.

I knelt, reached past my elbows, groped until I had some purchase, and began to lift. Heavy, wet, slimy, in that hollow, out of the wind and the sun, alone, suddenly I was birthing what had not yet been born. I knew I had in my arms something earthly, the fruiting body of a complex organism “without a body plan,” as Merlin Sheldrake puts it; and I also had hold of some chthonic part of myself that had been subsisting somewhere, utterly apart from who I thought I was. This part of me that might have remained untouched had I not found myself on my knees with a roughly 13-pound mushroom in my arms. It had the heft and density of a well-fed housecat. I had slipped into my mushroom, a place of exquisite vulnerability.

I knelt there for some time. The sky clouded over as it often does in the early afternoon west of the Oregon coast range. I knelt there pulling, lifting, and feeling with a terrible certainty a resistance I can only describe as intentional, mindful. I was unwinding something tangled, umbilical. I began to cry, but silently, biting my lips. I did not wish to wake whatever it was; instinctively I knew that noise would disturb this life not yet fully alive to itself. It had not been waiting for this moment, nor had I been waiting for it. It was not lost, and I had not found it. I had rescued neither it nor me. I was neither recovering something dormant nor recalling something long forgotten. Whatever existed as a coincidence of our encounter had never existed before. I stopped, held whatever it was, moist and sticky and cool against my aching forearms. A moment cradled in a spongy parenthesis, holding myself holding something that lived for as long as I held it, while slowly coming to realize that it would not survive in the air, on the surface. If I brought it to the surface, it would perish. Like the creatures surviving at abyssal depths in the sea, it would lose its creaturely integrity. If I wanted it to live, I could never see its full extent.

Once, in Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, I observed a sad exhibit of beluga whales. It seemed a particular kind of human wastefulness to set this huge tank of saltwater next to floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking a great freshwater lake. The beautiful whales swam rippling around and around their tank, coming to the surface near a shelf where I assumed they were fed fish. Belugas are social. Surfacing, they appeared not so much content as undismayed—prepared, perhaps, to be surprised. The half of what I’d raised above the duff had the shine of whale skin in water. The belugas meant no harm, and whatever it was that I held then didn’t, either. While I’m unprepared to call it good, it was not malevolent. It was, is all.

The memory of this experience is absolutely distinct from the actual experience; nothing like this had ever happened to me, and nothing has since. It’s just that now, years later, the time has come for me to word whatever happened then and there. I wonder: Have I ever been as close to another life as I was then, alone on my knees in the woods, that October day in the early aughts not quite half gone?

Did I lower it more slowly than I had raised it? I don’t know what took more time and care: the effort to lift it against faint but unmistakable resistance, or to lower it inches, to set it back where I found it, nestled in its resting place; the hollow where it had its being, which is not the same as saying it had a home there. Neither of us was at home in the sense of a stable place one might return to, or be welcomed. What took place then took place only in that moment when, of each other, we made something protean, centaurish. The time came to let go.

I walked to my backpack, tore up a paper bag, wiped the slime from my hands and arms. I must have wiped my eyes with my sleeve before I crunched a handful of potato chips, and then I went into those woods to work. I had mushrooms to pick. About an hour later, backpack full, I went down to the car, unloaded my fragrant treasure in the trunk, gulped the cold coffee, and legged it back up the road. I stopped at another flat spot I’d passed and found a copse of porcini, a mix of #1s and #2s. For a moment, I let myself believe that they had been waiting for me. On a nearby slope too steep to go down but that could be worked from the bottom up, scrambling, I gathered pounds of chanterelles. I went on: absorbed, elated, in each place lost until I relocated the gravel road.