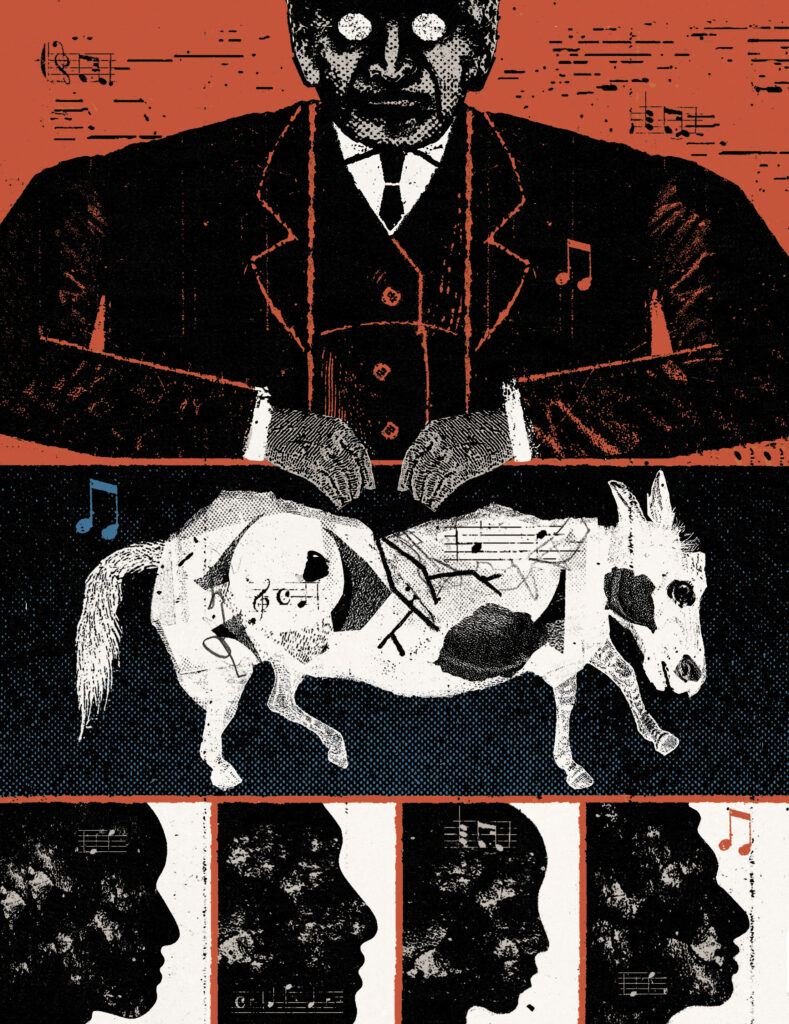

Several years ago, the musician Mike Mattison fixated on the story of how Charlie Idaho killed the Mercy Man. Mattison found it in The Land Where the Blues Began, a celebrated memoir and cultural history by the folklorist Alan Lomax. According to one of Lomax’s sources, Charlie Idaho was a powerful Mississippi levee contractor who once murdered an SPCA humane officer who’d come to inspect Idaho’s mules for abuse or overwork. “He walked Charlie Idaho’s line from end to end. Ain’t been able yet to find a mule with his shoulder well,” said Ed Lewis, a veteran levee camp laborer. “And Mr. Charlie killed the Mercy Man.”

Everything about the story spoke to Mattison, who has a degree in English and American literature from Harvard and now makes his living as a singer-songwriter, most notably for the Tedeschi Trucks Band. He was taken by the name Charlie Idaho, which struck him as both appropriately outsize and bizarrely out of place for a southern levee boss. He was even more fascinated by “the Mercy Man”—the idea that mercy could be embodied in a person, who could then be murdered. “And just realizing there wasn’t a ballad about it,” Mattison told me, “I just couldn’t believe that nobody else had bit on that.”

The result of these musings was “Charlie Idaho,” an eerily beautiful track from Mattison’s 2020 solo album Afterglow. Mattison sings with bitter resignation from the point of view of an eyewitness—“someone who was there, and who continues to be there”:

Every mule’s working when the levee breaks.

If the police don’t get you, it’s the cold and the snakes.

Charlie gonna fix it, whatsoever it takes,

And what are you gonna do?Charlie Idaho shot the Mercy Man,

Shot the Mercy Man,

Shot the Mercy Man.

Charlie Idaho shot the Mercy Man.

At least the poor boy died.

But Mattison, it turns out, isn’t the first musician to sing about the murder, and Idaho wasn’t the first “Mr. Charlie” to be accused of committing it. Lomax encountered at least three versions of the story during his decades of fieldwork, each one fingering a different levee boss for the crime. There’s a hazy, half-legendary quality to all of the accounts, but I’m increasingly convinced that they refer to a single historical event. And although I can’t prove it, I strongly suspect that Mattison’s “Charlie Idaho” is only the most recent contribution to a once-vital but almost completely undocumented lyric tradition.

To the eye, the Mississippi River levee is not all that striking—a modest, grassy slope rising 30 or 40 feet above the floodplain. But its subtlety belies its size. The levee system stretches from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, all the way to New Orleans. And because the earthen embankments follow, on both sides, the meandering course of the river and many of its tributaries, they collectively extend nearly 4,000 miles. It’s a truly massive human achievement, rivaling the Great Wall of China and the Pyramids of Giza.

And like those peers, the levee was built largely by a desperate underclass. Prior to the Civil War, a combination of enslaved men, convicts, and immigrant laborers worked along the river. After Emancipation, and the creation of the Mississippi Levee Board in 1879, Black men with few employment options entered what was effectively a peonage system when they joined a levee camp. Bosses forced them to work 16-hour days, housed them in flimsy tents surrounded by piles of trash and feces, and fed them stews of stale beans, greens, stalks, and roots. They withheld pay, drove men into debt by charging extortionate prices at the commissary and dealing them stopgap loans at 25 percent interest, and beat them with impunity. A worker could leave at his own risk, but he had no legal recourse; contractors and their henchmen were the law of the levee. “It is no exaggeration,” wrote the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins in 1933, “to state that the conditions under which Negroes work in the federally-financed Mississippi levee construction camps approximate virtual slavery.”

From that misery came a bittersweet music—specifically the slow-moaned, hypnotic work songs known as levee camp hollers. Men pushing wheelbarrows or driving mule teams filled the air with what Lomax called the “wondrous recitativelike vocalizing through which black labor voiced the tragic horror of their condition.” These hollers, along with the more rhythmic work songs of section and chain gangs, prefigured the Delta blues.

In 1938, Lomax recorded several original songs by Sampson Pittman, a blues guitarist and former levee worker from Arkansas who had recently moved up to Michigan. In “I’ve Been Down in the Circle Before,” Pittman recalled the dispositions of various contractors he’d known, including “Bullyin’ George Miller,” Charley Lowrance, and Forrest Jones. Lomax speculated that Pittman, “safe in his Detroit apartment, a long way from retribution and with the whiskey flowing,” felt free to name names:

There’s Mister Forrest Jones,

Ain’t so long and tall,

Killed the Mercy Man

And he like to kill us all.

Driving across Mississippi a few years later, Lomax picked up a one-legged Irish hitchhiker named “Black Hat” McCoy. A levee worker since the 1880s, McCoy was full of stories about how lawless the camps were. He told of how the commissaries used to sell cocaine, and how he’d lost his leg because a fellow worker had shot him “and the company doctor was drunker than usual that day.” Eventually he got around to the tale of “Charley Silas—the big contractor who made a million and, when he went broke, walked off in the river.” Silas, he said, was infamous for shooting “the Mercy Man, which was the humane officer out of Memphis. This fellow came out to Silas’s camp and protested against him working mules with sore necks and shoulders. … An argument came up over this and Silas shot the Mercy Man dead. It cost him fifty thousand dollars to get out of the mess.”

It wasn’t until 1959 that Lomax heard Ed Lewis, then an inmate at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, attribute the killing of the Mercy Man to Charlie Idaho. Lewis was careful to disclaim any firsthand knowledge of the event: “That happened way back in the twenties, when I was quite a baby,” he said. “Nothing I know, just something I hear.”

All three of those alleged killers were real levee contractors and bosses, and it’s not difficult to imagine any one of them shooting a man for inconveniencing him. Forrest Jones—grandnephew of the Confederate general and KKK cofounder Nathan Bedford Forrest—was notoriously cruel to his workers. Government investigations in the 1920s and ’30s identified his camps as dangerously unsanitary and criminally exploitative. Pittman wasn’t the only camp veteran to recall Jones in song. In a levee camp holler recorded by Lomax in 1942, Charley Berry (the brother-in-law of Muddy Waters) sang of “old Bullyin’ Forrest Jones.” Berry told Lomax he had decided not to work for Jones after seeing him viciously beat a Black employee with a root: “I don’t remember what kind of root it was, but I’ll tell you this: he wore hell out that n—— head with it.”

“Charlie Idaho” (a very southern mishearing of his real surname, Aderholdt) regarded the beating of Black workers as just another part of his job. When Lomax found and interviewed him in 1942, Aderholdt congratulated himself on having “never crippled a n——” in 46 years on the levee. “I’d go after them with a club or a whip,” he said, “never with my bare hands—a man would have been a fool to do that—and when I was through with them, they was better workers.”

Both Jones and Aderholdt appeared in the newspapers from time to time, usually in business- or society-page items, occasionally for some small legal trouble, but never for murder. And though the killing of Black men could, and did, go unreported in the papers and uninvestigated by the police, the killing of a prominent white man—an animal welfare officer, for example—would have created a stir.

Which is exactly what happened on June 28, 1909, when levee boss Charles Siler (not Silas) shot the Mercy Man at a camp outside Memphis. This story resurfaced last summer when I ran a newspaper archive search on the terms “humane officer” and “mercy man.” According to the Commercial Appeal, George F. Guernsey had paid a visit to Siler’s camp and found half a dozen mules too “sore” for labor. When a worker informed Siler that “the ‘mercy man,’ as the humane officer was known to the negroes, had corralled a bunch of his mules,” Siler confronted Guernsey and cussed him out. A witness testified that Guernsey was preparing to arrest Siler—which, as a special officer, he was authorized to do—when Siler shot him three times from behind.

It was Lomax’s one-legged hitchhiker, in other words, who had remembered the story correctly, only swapping out a couple of letters from the killer’s name. There’s no way of knowing whether Siler really spent $50,000 “to get out of the mess,” but McCoy was right that he dodged a conviction despite the apparently damning evidence against him. Siler pleaded self-defense, arguing that Guernsey had reached for his pocket as though for a gun, and 10 of the 12 jurors were persuaded; one of them was a shirttail relative of the Mercy Man. The judge declared a mistrial, the county’s attorney general vowed to re-prosecute, and Siler went back to work on the levee. In 1912, Engineering and Contracting magazine called him a man “who know[s] how to handle a negro and a mule as well as the average man knows how to handle his knife and fork.” Two years later, a single sentence in the Commercial Appeal noted that the murder indictment against “C. W. Siler, who killed a humane officer,” had been dismissed.

One fact that emerged incidentally from Siler’s trial testimony was that he had once killed a Black man, too. He didn’t say anything more about the circumstances, and the prosecutors didn’t ask, presumably because it wasn’t an extraordinary thing for a levee boss to admit—even while on trial for another murder.

Siler had almost certainly worked men to death, but he wouldn’t have considered those actions to be killings. That was just being a boss. “Main thing about it,” Big Bill Broonzy told Lomax, “is that some of those people down there didn’t think a Negro ever get tired! They’d work him—work him till he couldn’t work, see!” Another of Lomax’s informants described seeing levee men die from exhaustion and be buried on the spot by the next load of dirt. A phrase that folklorists heard again and again was, “Kill a n——, hire another. Kill a mule, buy another.” Mules were expensive, but Black men were expendable.

The sheer inhumanity of that calculus is another reason Mike Mattison finds the name “Mercy Man” so compelling. It appears to have been a Black coinage, and Mattison hears strains of what he calls “blues laughter” in it—the grimmest sort of gallows humor. “There are many things you could call this person, but they’re calling him a Mercy Man, and he’s coming to check out the mules,” Mattison told me. “Nobody’s coming to check out the men. I have to believe that the levee workers were well aware of this irony, this high irony. You could see somebody saying it with great disdain.”

Over time, the term seems to have acquired a second meaning. Several of Lomax’s sources told him that “the Mercy Man” referred to any powerful white man who was a friend to Black people and would intercede on their behalf. In “I’ve Been Down in the Circle Before,” Pittman seems to use the phrase in exactly this sense, singing,

Now Mister Charley Lowrance

Is the Mercy Man,

The best contractor, partner,

That’s up and down the line.

To a person acquainted with both definitions, then, the murder of the Mercy Man would be the epitome of levee boss cruelty—and the ultimate occasion for blues laughter: At last, here’s a white man who takes as much interest in the welfare of Black people as the rest of society takes in the welfare of mules. Our very own Mercy Man. And they’ve killed him. “That’s a very blues-minded view of the world,” Mattison said. “Like the blues itself, it’s funny-not-funny.”

It’s not surprising that as the details of the murder receded in memory, the story attached itself to different men. The most notorious levee contractors and foremen were easy enough to conflate. Socially and professionally, they were a cabal; newspaper searches for Charles Siler, Forrest Jones, Charles Aderholdt, Charles Lowrance, George Miller, and their ilk show them working for one another’s companies, marrying one another’s cousins, and carrying one another’s caskets. It didn’t hurt that an uncanny number of them were named Charles. In Black story and song since antebellum times, “Mr. Charlie” had been a generic name for a white “bossman.” “All the way from the Brazos bottoms of Texas to the tidewater country of Virginia,” Lomax writes, “I had heard black muleskinners chant their complaint against Mister Charley, but the score of singers all disagreed about his identity.” Who killed the Mercy Man? If levee bosses were just a bunch of interchangeable Mr. Charlies, then they all did.

The reason I suspect that the story of the killing circulated widely in lyric is the way Ed Lewis tells it to Lomax. On the recorded interview, Lewis has just finished singing a levee camp holler, and Lomax asks whom he was working for when he first heard it. “Charlie Idaho! Money man!” Lewis responds, and then rattles off a couplet: “Charlie Idaho give a part, and Mr. Blair give a drag. / Wasn’t no end to them dollars them two mens had.” Moments later, Lomax asks about the identity of the Mercy Man, and Lewis again answers with a rhythmic patter: “Aw, Mr. Charlie killed the Mercy Man! He walked Charlie Idaho’s line from end to end. Ain’t been able yet to find a mule with his shoulder well. And Mr. Charlie killed the Mercy Man.”

Lewis clearly prefers to parry each of Lomax’s questions with a familiar verse, if one comes to mind. His rhyme about the boss who gave “a drag”—incomplete payment of wages owed—was common on the levee. Likewise, “Ain’t been able yet to find a mule with his shoulder well” is a fragment of a floating verse: “Look all over the whole corral, / Couldn’t find a mule with his shoulder well.” Lomax writes that he heard those lines in every southern state, and they turn up on blues records by Texas Alexander and Mance Lipscomb. Mattison even includes a version of the mule shoulder couplet in “Charlie Idaho.”

Lewis’s answers to Lomax are a virtual anthology of migratory verses from levee camp hollers, and his near-rhyme about Mr. Charlie killing the Mercy Man is one of them. He delivers it so readily and so rhythmically that whoever transcribed the interview for the 2014 boxed set of Lomax’s Parchman Farm: Photographs and Field Recordings used internal quotation marks and included a slash to denote a line break.

Hollering such verses would have offered a rare release to levee workers. Withholding wages, overworking mules until their shoulders had harness sores, even killing the Mercy Man: these were quintessential levee boss behaviors, and if Black men were powerless to do anything about such cruelty, they could, at the very least, bear witness. It’s a tragic loss that so few hollers were recorded or preserved; as the scholar John Cowley has pointed out, they represent one of the oldest American protest song traditions.

So whatever became of Charles Siler? As it happens, that’s yet another question that Black Hat McCoy had already answered. On the morning of Saturday, April 14, 1934, just north of the Harahan Bridge in Memphis, Siler rose from the bank on which he’d been sitting and walked into the Mississippi. He entered the swift current, the Commercial Appeal reported, “as calmly as if he were entering a wading pool.” His body was recovered the following Tuesday, seven miles south of the city.

As delayed justice goes, it’s almost too poetic: Mr. Charlie seeking mercy from his lifelong nemesis, the river. It’s tempting to hope that Siler’s conscience was haunted in his final years, but his life up to that point suggests that his misery had a more prosaic source. He had always treated men (and mules) as means to an end, treated lives as measurable only by their monetary value. And by 1934, there wasn’t much money left in levee building. He was 74, long unemployed, and living alone in a Memphis hotel. Black Hat McCoy may have said all that needed saying about the interior life of Charles Siler: he “made a million and, when he went broke, walked off in the river.”

George F. Guernsey, the Mercy Man, was nearly 60 and a grandfather at the time of his death. He seems to have been genuinely brave and admirable. One article said he belonged to the Grand Army of the Republic, meaning he’d served the Union while still in his early teens. Three years before his killing, he had helped the Memphis police chief disarm a man who was firing a pistol on a busy street. Even after Siler had put three bullets in him, Guernsey seemed more concerned with his responsibilities than his own health. “I wanted to leave the mules and drive fast to the city with the wounded man,” said a trial witness, “but Guernsey insisted that the mules be driven on in, as he wanted to prove that he was right in taking the animals.”

Last summer, I went looking for Guernsey’s descendants and was surprised to find a cluster of them living in northeastern Kansas, not far from my home in Lawrence. They were fascinated to learn that people were still talking—and, occasionally, singing—about their ancestor’s death. Brock Guernsey, a great-grandson of George, told me that the family had only recently discovered the true story of the killing, when a genealogist aunt of his turned up some articles. Prior to that, he said, their dinner table retellings of it had drifted pretty far from the facts. In one version, Guernsey’s attempt to seize the mules had become an attempt to steal someone’s horses. That, in turn, had evolved into a family joke about being “descended from horse thieves.” The humane officer who died in the line of duty had done some time as the black sheep of the family. It’s a perfect coda to his story, if blues laughter is to your taste—a poetic injustice. Even in memory, there’s no mercy for the Mercy Man.