I gave no thought to a dining room. To the extent that I had a dining room at all, it functioned mainly as an office: my typewriter, during daytime hours, was placed on a table that my first husband saved from curbside trash pickup at his uncle’s house (I believe on our one visit) and that I ended up keeping after the divorce. It consists of one very long board of some sort of fairly thick wood and is quite heavy, though one wonky leg does make it slightly wobble. I see it now once a year, as it resides with friends in Florida. I always appreciated that it did double duty as a daytime desk and evening dining table, though it was so narrow that guests sitting opposite each other were practically nose-to-nose. A centerpiece would have been a problem, had I ever thought to have one.

Let’s just say I never particularly cared about reading House Beautiful or Southern Living (a gift from my grandmother, who was ever hopeful). But a guest room: once I had my own house, it was imperative to have a guest room. When I rented an apartment, there’d been a pull-out sofa—what else could I do?—but when I moved, I made sure the house had three bedrooms, with one immediately set aside for guests. Where else were visitors going to sleep, back in those days when the vast fields of the republic rolled on under the night? Who had money for a hotel? Who didn’t want to hang out with their friends as much as possible? Back then, even local dinner guests didn’t think to race home after a party so that they could compare notes with their significant other about how weird their friends had become, how materialistic (“What exactly are segregated funds? Did you understand a word of that?”), and how they couldn’t bear to listen to one more anecdote about the grandchild who’d been named for—who could believe it?—a musical instrument. (“Oboe? Oboe?”) Back then, no one felt the need to escape. Instead, they spent the night.

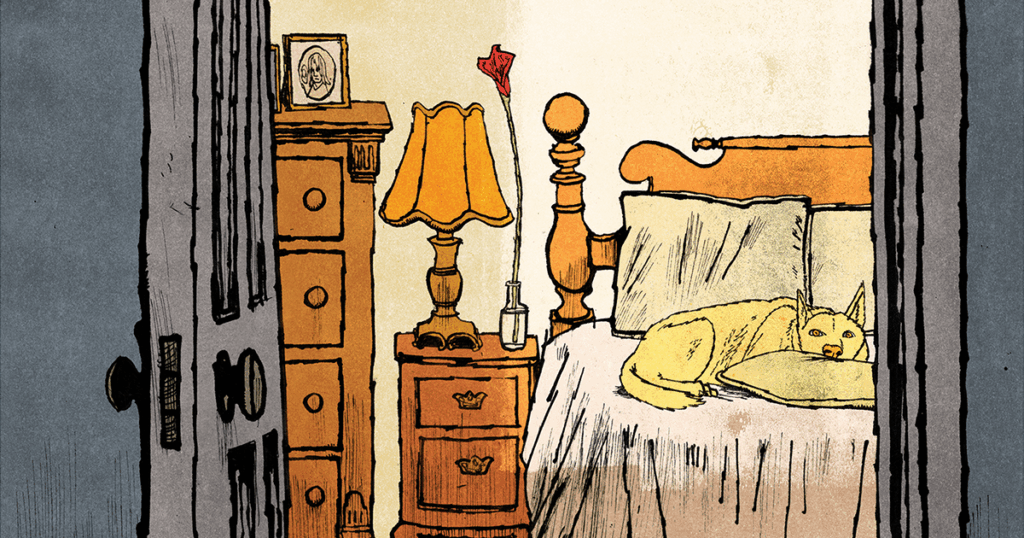

I realize that the whole concept of a room set aside for visitors can be viewed as ridiculous. Also, that it requires your beloved (second) husband of 37 years to climb up the ladder you otherwise vehemently insist he avoid, to hang the bargain chandelier ($50—no one wants such things anymore; most antiques stores are out of business), with its dangling dust-catching crystals that he tries to swat out of the way like gnats. Forget putting the fixture in the dining room: put it in the guest bedroom, along with the comforter that puts to shame the enormous white ensemble that Diana Ross wore to this year’s Met Gala, the most beautiful Turkish rug (before they began to weave in things like cars and helicopters), the handmade Michael Swanson chair, the Victorian dresser, the photographs leaning just so on the mantel. Best of all, the guest-room window looks down on an iron statue of a howling wolf set atop massive cinderblocks. The wolf’s delivery charge was equal to its purchase price, and its arrival resulted in (1) shutting up the plant nursery guy, who thought the craterlike area of our so-called lawn could best be used (this was his epiphany; he was so excited about it) for a firepit; and (2) one of the wolf’s delivery men saying, “Lady, that Buddha boy we delivered down at the corner was way lighter than this sucker.”

But let me better explain my feelings about the guest room in general. Sure, it’s a welcoming place for visitors—how nice, clearly related to Virginia Woolf’s well-known concept of a room of one’s own, even if my personal desire is not to live in such a room, but merely to peer into it from time to time. Also, if the room just sits there, it’s one area of the house that isn’t a mess. I don’t race to find a mattress, say, if someone shows up unexpectedly. I have raced to find pieces of missing furniture and other assorted objects. My husband is a painter and simply imports, from other rooms, convenient seating or props for the models who pose for him in his studio. Once, amusingly, I spent a year coming to terms with the fact that I must, indeed, have opened and enjoyed the bottle of Perrier-Jouët champagne that had been in the refrigerator door—I hoped I’d drunk it with others—and though I never found the bottle, I did see it again much later when visiting the Metropolitan Life building in St. Louis, where my husband had preserved it, like one of Keats’s figures on the Grecian Urn, in the mural he painted in the inner lobby.

I confess: I’m not a neat person. I aspire to be better at cleaning and banishing clutter, but I fail. I do not fail in the guest bedroom. Everything has been put there to suggest the absence of everything else that might have been included: for lighting, there’s only a modest finial screwed atop the bedside lampshade, below which is a bud vase so tiny, it can barely hold a single thin-stemmed blossom—none of those sparkling, battery-operated faux branches that get turned on in lieu of an overhead light. At least to me, the untouched guest room is lovely, with fine pillows and, I hope, inspiringly uncoordinated sheets with a thread count equal to the number of grains in a container of Morton salt. And the linens collected over the years (shout-out to you, Yves Delorme, via the downtown mall in Charlottesville, Virginia) and delicately laundered. So is the room also my life unlived? It is certainly my life unslept. My dream of someone else’s experience of a dream. It’s meant to be someone else’s haven, someone I don’t aspire to be, but rather a temporary sanctuary that I pretend my guests will happily inhabit, looking down on that iron wolf before lowering the blinds and going to sleep.

It’s true: We’re lucky to have the extra room. To have a house. Friends who want to visit. All of that. Sometimes when it’s newly empty, I loiter outside the doorway, feeling the presence of the person who’s just left, or—far less sentimental—I purse my lips, knowing what laundering awaits me. One morning, after a friend and her dog had left, the dog having moved a decorative satin pillow to the center of the bed, the better to nestle with, I stood in the doorway and saw the dog. There he was, looking up at me, unmistakable guilt in his eyes. That dog knew what I was going to say. Except that I said nothing. I kept quiet. And in those few seconds before I continued on my way, the dog, whose name I could reveal, though I wouldn’t want his “person” (as we now say) to know, simply lowered his head once again, either to return, or to pretend to return, to the comfort of sleep.