Affirmative Inaction

Opposition to affirmative action has drastically reduced minority enrollment at public universities; private institutions have the power and the responsibility to reverse the trend

In his 1965 commencement address at Howard University, President Lyndon Johnson declared, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.” The affirmative-action approach President Johnson proposed in that speech was to be a moral and policy response to the losses, both material and psychological, suffered by African Americans during and after the time of slavery: “We seek not just freedom but opportunity—not just legal equity but human ability—not just equality as a right and a theory, but equality as a fact and as a result.” Johnson’s speech was followed in 1965 by executive orders aiming “to correct the effects of past and present discrimination.” Universities and colleges across the land soon adopted affirmative-action policies. More than 45 years have passed since that June afternoon on the Howard campus. What is the fate of Johnson’s triumphant vision in the world we now occupy?

If you listen to Roger Clegg, who heads up the Center for Equal Opportunity, a conservative think tank devoted to “colorblind public policy,” the answer is that the practice of affirmative action in higher education has put the country on the path to grievous error. Clegg believes, as he said in a 2007 speech to the Heritage Foundation, that the policy “passes over better qualified students, and sets a disturbing legal, political, and moral precedent in allowing racial discrimination; … it stigmatizes the so-called beneficiaries … fosters a victim mindset, removes the incentive for academic excellence, and encourages separatism; it compromises the academic mission of the university and lowers the overall academic quality of the student body.” He contends, as do his many allies, that anything diluting academic excellence hurts teachers and students alike because colleges and universities exist primarily to protect and exalt the life of the mind.

A very different response to Johnson’s speech came, 38 years after its delivery, from within the chambers of the United States Supreme Court. In 2003, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, having just voted on two cases involving the admissions policies of the University of Michigan, predicted that affirmative action would soon end because it would no longer be needed:

Finally, race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time. The Court takes the Law School at its word that it would like nothing better than to find a race-neutral admissions formula and will terminate its use of racial preferences as soon as practicable. The Court expects that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.

We stand, as a country, somewhere amid President Johnson’s vision, Roger Clegg’s hostility, and Justice O’Connor’s expectation. Anyone interested in higher education should want to contemplate, on behalf of colleges and universities, students and faculty, alumni and paying parents, the fate of affirmative action. How should it now play out on campus after campus? Will it continue until the year 2028? If not, why not? If so, should it then end? If not, for how long should it be sustained?

To begin to answer these questions, it is important to acknowledge the educational milieu in which affirmative action has been practiced. Two fundamental ambitions have long characterized the culture of our colleges and universities: they have sought to be meritocracies, and they have sought to be egalitarian communities. The first goal gives primacy to intellectual accomplishment, the second to community rapport. Students are prompted by the first to demonstrate their full mental powers, by the second to be citizens of what Plato’s Republic as well as John Henry Newman’s ideal university were to be: a model commonwealth. In his book The Idea of a University, Newman said, “I cannot but think that statesmanship … is learned, not by books, but in certain centres of education.” The one is not the other. “Being as smart as you can be” is only hazily connected to “learning from each other in a mutually beneficial way.” The tension between the two is never resolvable; that tension is where arguments about affirmative action find their campus home.

Those people who champion affirmative action assert that much of what education offers is social, participatory, and communal. Enrolling students of many different ethnic backgrounds and of unequal educational achievement, they say, only helps the institution and, again, its students. They believe that the educational process is itself corrupt if it does not bring together the full spectrum—the diversity—of American young people. Using the helping hand, they argue, means creating a better education for everyone and fulfilling a civic obligation to enroll a given number of students for the purpose of creating a stronger and more democratic society.

The history of affirmative action includes the graduation of thousands of young men and women who otherwise would not have passed within the gates of a college or university. Many of those graduates have gone on to professional careers where their success has helped to reinvigorate the American dream. They have become physicians, diplomats, lawyers, Army officers, stockbrokers, journalists, high government officials, scientists, and business leaders. Why, advocates of affirmative action now ask, should their number not be augmented?

But before all else, it’s worth asking whether affirmative action is really needed. For all their differences, both critics and advocates acknowledge that some classes of students, particularly African-American and Hispanic, cannot gain admission to many colleges and universities solely on the basis of their academic preparation. They need preferential treatment to enter the model commonwealth. The College Board last measured mean Scholastic Aptitude Scores by Ethnicity in 2008; the results are sobering:

Group Critical Reading Mathematics Writing Asian 513 581 516 Black 430 426 424 Mexican American 454 463 447 White 528 537 518 All 502 515 494

In critical reading, African-American students scored, on average, 83 points below Asian-American students, who in turn scored less well, by 15 points, than white students. But in mathematics, Asian-American students trumped both whites and African Americans, by 44 points and 155 points respectively. In writing, whites did just about as well as Asian Americans (two points higher) and considerably better than African Americans (94 points higher). And in every category, Mexican Americans did less well than whites and Asian Americans but better than African Americans. With such dissimilar scores facing them over the years (the year 2008 being little different from the previous five years), admissions officers at colleges or universities have introduced handicapping measures in order to admit applicants with weaker scores. Those measures have hardly been trivial.

One important set of studies, by Thomas Espenshade of Princeton University and his colleagues, examined the records of more than 100,000 applicants to three highly selective private universities. They found that being an African-American candidate was worth, on average, an additional 230 SAT points on the 1600-point scale and that being Hispanic was worth an additional 185 points, but that being an Asian-American candidate warranted the loss, on average, of 50 SAT points.

What happens if the handicapping is taken away? The same authors found that the outcome would be dramatic, with acceptance rates falling for African-American applicants from 31 percent to 13 percent and for Hispanic applicants by as much as one-half to two-thirds; Asian-American applicants would occupy four out of five of the seats created by fewer African-American and Hispanic acceptances. The Asian-American acceptance rate would rise by one-third from nearly 18 percent to more than 23 percent. Most astonishingly, it turns out that—contrary to the assumptions of those who contend that affirmative action puts white students at a severe disadvantage—white applicants would benefit very little from the removal of racial and ethnic preferences; their acceptance rate would increase by less than one percentage point.

Given the probable results of eliminating affirmative action—a student body consisting almost wholly of whites and Asian Americans—no chief administrator of a respectable college or university would happily oversee the erosion of the presence of black or Hispanic students. That is why no such institution has volunteered to be first to proclaim that it will formally jettison affirmative action. In order to protect what they see as the positive results of the practice and also to protect themselves against litigation by a white plaintiff arguing that his or her chance of admission has been jeopardized, colleges and universities have increasingly relied on admissions standards that depend less on SAT scores and more on intangible and personal attributes: having leadership skills, having the strength to overcome social and economic circumstances, or being the first in the family to seek higher education. With such careful consideration, the candidates can then be admitted (or rejected) one by one.

But careful consideration of this sort is expensive. It requires many people to read, with sensitivity, thousands upon thousands of files, and to make judgments requiring a delicate understanding of the abilities and character, the social background and the hidden promise, of the young people represented by those files.

The two celebrated cases emerging from the University of Michigan, about which Justice O’Connor made her memorable remark, illustrate the situation faced by a leading public institution practicing affirmative action. The Supreme Court employed “strict scrutiny” in reaching its decisions. And, as the Court saw, when the university itself employed careful scrutiny in its admissions procedures, it was entitled to an important victory.

One case addressed the admissions policies of Michigan’s law school (Grutter v. Bollinger et al.); the other addressed undergraduate admissions in its college (Gratz et al. v. Bollinger et al.). The former found for the university, declaring, “The narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body is not prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause.” The latter decision found against the university, noting that its “current policy, which automatically distributes 20 points, or one-fifth of the points needed to guarantee admission, to every single ‘underrepresented minority’ applicant solely because of race, is not narrowly tailored to achieve educational diversity.”

For the Court, narrow tailoring was the factor on which its decisions turned. The Court asked the university if candidates for admission had been considered one by one (“holistically,” in the parlance of admissions officers) or if each had been given a unique profile based on factors both quantitative and qualitative. The law school responded with a record of showing it had considered candidates one by one; the undergraduate college hadn’t done so. The college automatically gave considerable weight to race, doubtlessly because of the number of candidates it annually faced, more than 25,000. Only by gross mechanistic methods could it pluck out those to be admitted from such a profusion of applicants. The applicant pool faced by the law school was much smaller and therefore greater care could be devoted to each dossier.

[adblock-left-01]

The distinction between the two cases is sharp, and the lesson deriving from it is crucial. First, the Court located a compelling constitutional interest in student diversity; race and ethnicity could be taken into account in admissions (provided that narrow tailoring is practiced) even when the government did not find specific discrimination. Moreover, the Court acknowledged that the composition of student bodies presents unusual, vital, and sensitive considerations. While it said that the big 20-point automatic advantage was no longer there for the taking, it also declared that colleges and universities could, if they wished, adhere to procedures both labor intensive and expensive, but neither mechanistic nor entirely quantitative, to arrive at the goal of genuine racial diversity.

Upon hearing these two decisions, the University of Michigan could declare a real, if partial, victory. But its satisfaction was short-lived. In the immediate aftermath of the Court action, the citizens of the state reared back and passed, by a decisive margin, the “Michigan Civil Rights Initiative,” amending the state constitution to prohibit state agencies and institutions from operating affirmative-action programs granting preferences based on race, color, ethnicity, national origin, or gender. The amendment, having decisively passed with 58 percent of the vote, became law in December 2006.

Similar action had been taken a decade earlier in California. Citizens there voted Proposition 209 into law in November 1996, with 54 percent of the vote. It banned every form of discrimination on the basis of race, sex, or ethnicity at any public entity in California. Within little less than a decade, black enrollment in the freshman class at UCLA had dropped from 211 to 96 and at UC Berkeley from 258 to 140. In the state of Washington, Initiative 200, which passed in 1998, ordered public agencies to cease giving preferential treatment on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin. It effectively ended affirmative action by state and local governments in hiring, contracting, and school admissions. This law was approved by 58 percent of the voters. Elsewhere and earlier (Hopwood v. Texas, March 1996), a federal circuit court had curtailed affirmative-action programs at public colleges and universities in three other states (Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi). In Florida, Governor Jeb Bush simply issued an executive order banning affirmative action. In the California and Michigan cases, Ward Connerly, once a regent of the University of California system, led campaigns barring the use of racial preferences. Before the elections of November 2008, with the ambition of introducing legislation banning affirmative action across the country, he took aim at Nebraska and Colorado. In the former, a proposal to ban affirmative action passed handily; in the latter, a similar proposal failed by a very small margin. And in November of 2010, Arizona voters approved Proposition 107; it bans consideration of race, ethnicity, or gender by any unit of state government, including the state’s public colleges and universities.

Referendums are one thing; public opinion is another. When it comes to what Americans feel about the practice, polls reveal that positive attitudes toward affirmative action in college admissions, while always in flux, are usually in jeopardy. Back in 2003, Gallup revealed that 69 percent of those asked thought that merit alone should be weighed in college admissions. Three years earlier, an Associated Press poll indicated that 53 percent of those polled thought affirmative action should be continued in admissions, with 35 percent saying it should be abolished. The same year, a Time/CNN poll showed 54 percent disapproval of affirmative action and 39 percent approval. A CBS News Poll in January 2006 revealed that 12 percent of those responding believed that affirmative action should be ended immediately; 33 percent said it should be phased out; and 36 percent believed it should be continued. The latest poll (from Quinnipiac University) reported in 2009 that affirmative action is opposed by 61 to 33 percent of those responding (with black voters supporting it by 69 to 26 percent and Hispanics by 51 to 46 percent). Such shifting attitudes provide nothing but chilly comfort to champions of affirmative action.

On a variety of fronts, then, the practice now faces more resistance in this nation than ever before. Should another affirmative action case be granted certiorari by the United States Supreme Court, there is every reason to think that it will meet determined resistance by all the conservative justices.

In the face of that resistance, colleges and universities themselves are silently backing away, bit by bit, from affirmative action. Data from more than 1,300 four-year colleges and universities in the United States show that the use of race and ethnicity in admissions declined sharply after the mid-1990s, especially at public institutions. The proportion of public four-year colleges considering minority status in admissions has fallen from more than 60 percent to about 35 percent. Among private institutions, the drop during the same years has been notable but less dramatic, from 57 percent to 45 percent. The major decline came after 1995, when the campaign against affirmative action intensified, and schools, particularly public ones, thrown on the defensive, retreated. They were reacting not only to actual litigation but also to its threat. While colleges and universities that are considered elite are more likely to have practiced affirmative action and to have been more protective of it, even they have retreated. Few innovative or vigorous forms of affirmative action are now in play in the face of courts and federal agencies exercising strict scrutiny when examining admissions procedures and in the face of an increasingly suspicious citizenry.

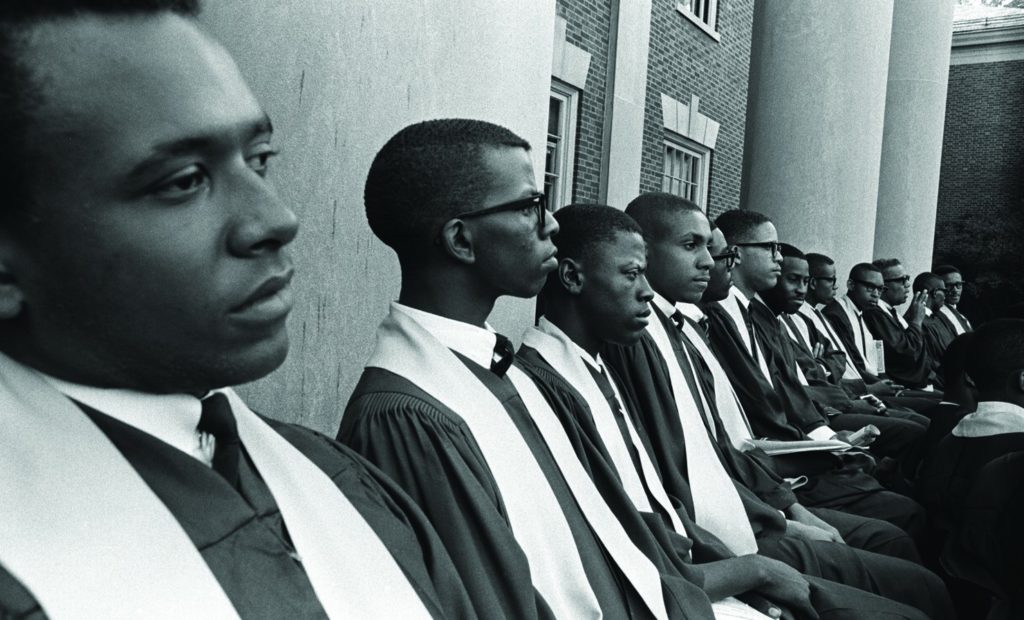

President Johnson at the 1965 commencement at Howard University (LBJ Library Photo by Yoichi Okamoto)

Another reality is redefining, and probably weakening, the meaning of affirmative action. Although few schools publicize the fact, one of the central historic principles giving rise to affirmative action is being undermined. President Johnson’s speech assumed that affirmative action would help the descendants of former slaves (he made no mention of Hispanics). That assumption from yesteryear is out of sync with today’s realities. Affirmative action more and more functions to open the campus not only to the descendants of former slaves but to black students with different cultural and political heritages. Once championed, as in Johnson’s speech, as a means of reparation or restitution, affirmative action now turns out to be helping hundreds and hundreds of young people who have suffered the wounds of old-fashioned American racism little or not at all. More than a quarter of the black students enrolled at selective American colleges and universities are immigrants or the children of immigrants. African-American students born in the United States thus turn out to be more underrepresented (given their presence in the U.S. population) at selective colleges than one might imagine. At some of the most exclusive institutions (Columbia, Princeton, Yale, and the University of Pennsylvania), no less than two-fifths of those admitted as “black” are of immigrant origin. Such facts, as they come into view, blunt the force of arguments favoring affirmative action. Diversity and restitution are better reasons than diversity alone, but restitution seems less and less in play.

Diversity itself, moreover, seems weaker and weaker as an argument for affirmative action when many campuses now appear, at least to the public at large, more diverse than ever before. The increasing presence on campus of students from myriad ethnic groups (Indian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Korean, Iranian, and many others) and the consequent reduction of “white” students (witness student populations at the University of California at Berkeley, UCLA, Stanford, USC, Columbia, and other schools) undercut the notion that American higher education is still unfairly monochromatic.

Yet another reason lies behind the decline, in practice, of affirmative action: it is expensive—in more ways than one. A large proportion of students benefiting from affirmative action benefit from financial aid. As administrators, facing breathtaking drops in endowment and thus endowment income, constantly scrutinize budgets to find ways to strip out costs, they look hungrily at the sizable amount of money that could come from tuition income (an asset) that is lost in financial aid (a liability). They remain aware of the institutional commitment to the social good of affirmative action and of the model commonwealth; but as officials responsible for the fiscal health of the schools where they work, they know the cost of supporting such a social good. The tension between doing what is right for society in the largest sense and keeping the school solvent bedevils such administrators. Nonetheless, as the tension is resolved, affirmative action is further compromised.

Facing this kind of opposition—legal, public opinion, and fiscal—what, then, is the likely future of affirmative action? We return to Justice O’Connor’s remark about 2028. She was, I think, wrong if she was making a prediction. (And, indeed, she has backed off the remark.) Affirmative action will still be needed to fortify the model commonwealth, and it will still be needed given the continuing gap in tested academic preparation between black and Hispanic students and others. Thomas Espenshade, the Princeton professor who has studied admissions numbers, predicts that, given the slow rate of convergence in test outcomes between black and white students, “it is likely to take another century to reach parity.” And for all that time, affirmative action will likely meet with opposition in the courts and in public opinion almost everywhere it is practiced. But the differences between public and private institutions suggest a solution to the legal and ethical challenge presented by affirmative action.

Public institutions, post-Michigan, will continue to confront vigilant and skeptical adversaries determined to discover if the admissions procedures at such places are flouting the law by allowing affirmative-action policies to fly below the radar. When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented in Gratz et al. v. Bollinger et al., she commented that there was one thing worse than racially divisive admission policies, and that was “achieving similar numbers through winks, nods and disguises.” No public institution can now afford the slightest risk of contriving artificial and bad-faith circumventions of the law.

But private institutions are different, very different. Their relative insulation from courts (because they do not take much public money) and referendums allows them to protect affirmative action more steadfastly than public institutions can. One person at the center of the Supreme Court’s decisions in 2003, Lee C. Bollinger, who was president of the University of Michigan from 1996 to 2002 and is now president of Columbia, a private university, told The Chronicle Review in 2007, “I am glad that independent institutions retain the autonomy to support diversity efforts that make our graduates more competitive candidates for employers and graduate schools, as well as better informed citizens in our democracy and the world.” And former Justice O’Connor herself, perhaps imagining the years from now until 2028, observed in 2007 the irony that private colleges, not covered by state bans on preferences, may—by virtue of that autonomy—end up being more diverse in their enrollments than public colleges.

But oddly enough, private colleges and universities may turn out to be relatively less attractive targets than public institutions for some potential litigants. That is because anti-affirmative-action organizations, such as the Center for Equal Opportunity (led by Linda Chavez and Roger Clegg) or its companion-in-arms, the Center for Individual Rights (led by Terence J. Pell), which might be expected to bring suits pleading reverse discrimination against selective public and private institutions in equal measure, strongly favor individual rights and generally dislike intrusions on what they deem as institutions not established by the government. Jonathan Alger, senior vice president and general counsel at Rutgers University, follows these issues closely and has observed that public institutions, as taxpayer-supported entities, are often seen by such organizations as more attractive targets for litigation involving the application of federal anti-discrimination law.

Hence, if they are prepared to spend the money to admit students “holistically,” one by one, and if they are comfortable with some admitted students whose board scores and grades are noncompetitive but whose individual promise is compelling, private schools can hold on to some level of affirmative action. Like public institutions, however, they cannot afford to disregard budgetary reality: affirmative action never comes free.

But why should private institutions and their leaders continue to carry the banner of affirmative action? The answer resides in the cultural and historical environment in which many of those schools were founded and in the separation from the world around them that they chose upon that founding. Many of them (Quaker, Roman Catholic, Methodist, and Presbyterian) grew out of deep religious or spiritual conviction; others were quickened by imperatives arising from the dreams of ambitious founders, such as Leland Stanford, John D. Rockefeller, and Ezra Cornell. Several of them—the Ivy League schools, Stanford, Duke, Rice, Chicago—are now among the most prestigious (and wealthiest) academies in the nation. Self-directed, they owe much of their success to the individual aspirations they have championed and cultivated. For schools with such histories, the appeal of marching to a drummer not put into position by the state will always prove attractive. To them, I believe, we must look not only to preserve the civic value of affirmative action, but to redeem it in the eyes of the nation.

But they are and will continue to be playing against the odds. While they can be comforted by their origins—secular or religious, but always independent—they will have to live with the fact that the public at large has an ever-declining interest in the central buttress for affirmative action: the model commonwealth. But for those living on campuses where different moral concerns resound, the formation and protection of that commonwealth has been an abiding goal, decade after decade. In response to those moral concerns, the private institutions must act, explicitly and publicly; their policies of recruitment and admission should be intentional, painstaking, and undertaken proudly.

[adblock-right-01]

Just how determined and tenacious will they have to be? Courageously so, for all of the reasons I have given. Moreover, they must be especially attentive to one particular chapter of American history—a distressing one—as it has unfolded in this country. That chapter, about African-American males, reveals just how difficult the future of affirmative action will be. The dwindling population of African-American males on college campuses over the last four decades marks the most stunning failure in sustaining the model commonwealth. It also illuminates how limited universities and colleges are in what they can do, even if unconstrained by courts and public opinion.

While the proportion of black students on American college and university campuses, both public and private, rose from 9 percent in 1976 to 13 percent in 2004 (with blacks continuing to represent about 12 percent of the national population), the proportion who were men was the same in 2002—4.3 percent—as it was in 1976. Thirty years ago, 43 percent of undergraduate degrees conferred on African Americans were won by males, but by 2002/2003 that percentage had dropped to 33 percent. Black women, however, continued an ascendancy uninterrupted for years. According to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, black men represented 7.9 percent of the 18- to 24-year-olds in the U.S. population in 2000, but they constituted just 2.8 percent of undergraduate enrollments in 50 of the best public universities in the nation in 2004. In each of the 30 flagship universities, fewer than 500 black male undergraduates were enrolled that year.

Even after being enrolled, less than half of all black male students who start college at a four-year institution graduate in six years or less, a rate more than 20 percentage points lower than the white graduation rate. That is not good news: it is the lowest college completion rate among all racial groups for both sexes. Perhaps most striking about these discouraging figures is that many black male students at some of the best institutions would likely not be enrolled at all if they were not athletes. The same Joint Center study reveals that more than one out of every five black men at 21 flagship public institutions was a student athlete in 2004. At 42 of these universities, more than one out of every three football players was black. At 38 of those schools, 50 percent or more of the basketball team was made up of black men. A dispiriting way of putting this is to say that, without their presence on many campuses to field teams in basketball and football, black males would barely exist in the model commonwealth. One goal of affirmative action, then, a campus fully representative of the diversity of the nation, can be achieved only when black males are present as students in proportion to their presence in the nation as a whole, and not just as athletes who also happen to be students.

If African-American males are underrepresented in colleges or universities, they are overrepresented in federal, state, and county prisons, jails, and juvenile detention facilities. About one in three black men will go to prison in his lifetime, compared to one in 17 white males. One in three black men between the ages of 20 and 29 already lives under some form of correctional supervision or control. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that some 186,000 black males between the ages of 18 and 24 were behind bars in federal and state prisons and local jails in 2005.

No amount of affirmative action, at either private or public colleges and universities, will free these men from jail. Nor will affirmative action be able to reach into the homes, neighborhoods, and schools to rectify the distressing situations—poverty, drugs, families customarily without either husband or father—that once served such men, and will now serve others, so badly. Nothing that colleges and universities can do will be enough to rewrite the history of racial inequality that has, for decade after decade, poisoned this nation’s history. Black men in prison are a function of that poisonous history, and affirmative action is a societal antidote to this and other existing effects of racism. We must not forget that history. History matters.

Private universities and colleges now stand at the center of this national drama. The burden upon them is great, and so is the weight of energetically sustaining the ideal of a model commonwealth. Nothing less than the essential civic and moral meaning of these schools is at stake. They must, because they can, act in ways that public institutions of higher learning now seem precluded from doing. The way forward since 1964 has been difficult; the way forward from 2010 will be even harder. But this difficulty can be eased just as so many American problems have been eased in the past: with a combination of individual desire and private money. This approach can make the process of admission thorough, detailed, and vigilant in recognizing promise in the lives of the next generation of American young people.