As American classical music came of age in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, composers were confronted with the fundamental question of what their music ought to sound like. To those artists schooled in the German Romantic tradition, for whom the symphonies of Schumann and Brahms were models to be imitated, American music was nothing more, nothing less, than a continuation of a European lineage that stretched back to Bach. Other composers were more consciously interested in creating a recognizably American music. But what exactly constituted an American sound? When Antonín Dvořák spent a few years in New York City and Iowa in the 1890s, he implored American composers to forge a national music based on black American and American Indian melodies, to do in this country what Edvard Grieg, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Dvořák himself were doing in theirs, that is, to invigorate their art with the richness of folk and indigenous material.

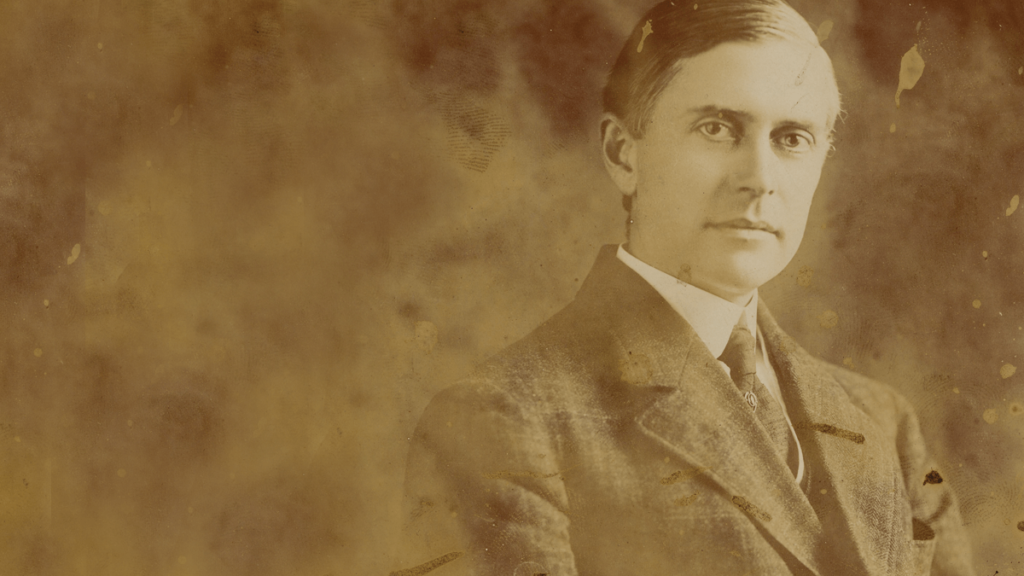

Among the first composers to take this exhortation to heart was Arthur George Farwell (1872–1952), a man very much forgotten today and yet, for a period of about 25 years, an important and influential figure in American music. He was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and studied engineering at MIT, but his desire to pursue a life in music led him to study composition in Europe. Farwell’s early artistic endeavors lacked a certain focus, but all that changed after his seminal encounter with the work of Alice C. Fletcher. An ethnologist and anthropologist affiliated with the Peabody Museum at Harvard, Fletcher was primarily interested in the Omaha Indians. She and the prominent Native American ethnologist Francis LaFlesche (whose father was the Omaha chief Iron Eye) worked closely together, recording the songs of the Omaha with a cylinder phonograph. These recordings formed the basis of Fletcher’s study Indian Story and Song from North America, which appeared in 1899.

Farwell found the book somewhat uninspiring at first. Specifically, he was convinced that the songs’ harmonies—which were not of Omaha creation but were supplied by one John Comfort Fillmore, author of a book called The Harmonic Structure of Indian Music—to be problematic. When Farwell returned to the songs sometime later, however, it occurred to him to strip away the harmonies and sing the unadorned melodic lines aloud. Now, an entire world of feeling and sensation opened up before him. He felt an affinity for the music that extended beyond the aesthetic into the realm of the spirit. Having recently immersed himself in the mythological foundations of Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle, Farwell now saw similar potential in these Omaha songs. American Indian music in general, he realized, could form the basis of an American classical music. Yet no publishers were willing to put out such music. So in 1901, Farwell founded the Wa-Wan Press (named for a ceremony of the Omaha people) in Newton Centre, Massachusetts. Farwell would go on to become the most notable exponent of the so-called Indianist school, whose composers were active during the first two decades of the 20th century. His stewardship of the Wa-Wan Press, dedicated to the publication of all contemporary American music, Native and otherwise, was every bit as significant an achievement.

Through this fledgling enterprise, Farwell published his first major work in 1901: the American Indian Melodies, 10 piano pieces drawn almost completely from source material in Fletcher’s book. Over the years, Farwell would reimagine the pieces in different guises, scoring three for baritone and piano in 1908. One of these, The Old Man’s Love Song, which evokes both the sunrise and the soft autumnal glow of a tribal elder’s final years, he set again in 1937, this time for eight-part mixed chorus. In the hauntingly beautiful version for baritone and piano, the singer declaims his lines boldly, as if in defiance of the passage of time, yet he also delivers more pensive phrases, which sound like nostalgic sighs, or rays of dying sunlight. Conjuring up sensations of wistfulness and loss, The Old Man’s Love Song is steeped in a languid atmosphere enhanced by the chromatic harmonic writing in the piano part, which is reminiscent at times of Wagner. I find this stylistic tension to be telling, given Farwell’s feelings about the pervasiveness of Germanic influences on American composers at the time. Since “our national musical education, both public and private, is almost wholly German,” he wrote,

we inevitably, and yet unwittingly, see everything through German glasses. … Therefore the first correction we must bring to our musical vision is to cease to see everything through German spectacles, however wonderful, however sublime those spectacles may be in themselves!

On the evidence of his early work, Farwell may have wished to cast off his German models, but he could not yet forget the alluring harmonies of Parsifal and Tristan.

The Omaha melody of The Old Man’s Love Song stayed with him, so much so that he used it again in a 1902 piano piece called “Dawn.” Here Farwell also incorporated a melody of the Otoe people, a hymn-like utterance that gains in intensity and sonorous power, in stark contrast to the flowing material that precedes it—which seems to have emerged from the Romantic realm of 19th-century piano playing. Another keyboard piece of the period, The Domain of Hurakan, shows just how much Farwell was still indebted to the Romantic modes of the 19th century, its genial, Joplinesque opening giving way to a tumultuous central section developed in the manner of Chopin.

Farwell’s music would lose many of these Romantic characteristics after his first journey to the West, undertaken in the autumn of 1903. He explored pueblos and Indian reservations, gazing in wonder at the sublime beauty of the desert—to Farwell, a love of Native American cultures was inseparable from a veneration of the land. Indeed, his first sight of the Grand Canyon put him in a rapturous state: “I sat there watching the lights and shadows play and change over the strange distances and depths of this wonderworld,” he later recalled, “and heard the unwritten symphonies of the ages past and the ages to come.” (Half a century later, the Sonoran Desert would similarly inspire Elliott Carter, who came away from a year’s sojourn in Arizona with one of his first masterpieces, the String Quartet No. 1.)

In 1904, Farwell traveled to Southern California, where he lived for a time with the anthropologist Charles Lummis. During this period, Farwell transcribed hundreds of Native American songs, primarily of the Cahuilla people, and composed some of his most popular pieces. One of these, the Navajo War Dance No. 2, was originally written for piano and later scored for mixed chorus. It’s a study in complex, spiky rhythms played out against a steady ostinato (or constantly repeating) pattern—playful, despite the warlike subtext, it builds to a frenzied finish. Another work, Pawnee Horses, also exists in two versions: as an exquisite piano miniature filled with luminous chords, the rhythmic figures conveying the gentle gallop of the eponymous beasts, and a choral arrangement that is somehow more jubilant, more exultant, certainly more frenetic. Farwell’s trajectory as an Indianist composer would culminate in his 1923 string quartet, The Hako, inspired by a ceremony of the Pawnee tribe, an ambitious work that incorporates Native American motifs into the context of large-scale sonata form. After this, Farwell’s interests largely led him into markedly different terrain, both thematically and stylistically. His suite The Gods of the Mountain, for example, orchestrated in 1928, is especially pleasurable—magical and incandescent throughout. Still later, he dabbled in thornier harmonic modes.

A few weeks ago, I had a chance to hear several of Farwell’s Indianist pieces on a program at the National Cathedral, part of the PostClassical Ensemble’s illuminating two-night festival devoted to Indianist and Native American music. The pianist Emanuele Arciuli played the original versions of Pawnee Horses and the Navajo War Dance No. 2 and was joined by the baritone William Sharp, who sang the Three Indian Songs. The cathedral’s chamber choral ensemble, Cathedra, also performed a capella arrangements of Pawnee Horses, The Old Man’s Love Song, and the Navajo War Dance No. 2. These were all committed, persuasive, and passionate readings and made a case for Farwell as an American composer of considerable interest. Yet judging by the highly dismissive review of the performance by Anne Midgette in The Washington Post and the comments flooding in soon after—the main objection being the presence of so many white men on a program of Native American–themed music—Farwell remains a figure of some controversy. In other quarters, criticism of the composer often has little to do with musical technique, and everything to do with who Farwell was—a white man deemed guilty of cultural appropriation.

To be sure, we can look back at Farwell’s interactions with Native American cultures, and find him lacking in certain areas. The musicologist Beth E. Levy, who discusses Farwell extensively in her book Frontier Figures: American Music and the Mythology of the American West, writes that the composer’s attitudes toward Native Americans “never completely slough[ed] off their skin of exoticism.” Moreover, she writes, his championing of Native music was predicated on the acceptance of the white man’s dominion over indigenous peoples as well as the tragic consequences of westward expansion. “When one race conquers, absorbs, or annihilates another,” Farwell wrote in 1903, “the spirit, the animus of the destroyed race invariably persists, in the end, in all its aspects,—its arts, customs, traditions, temper,—in the life of the conquering race.” That animus may have given vitality to Farwell’s art, but who would dispute the notion that such art, by definition, was born out of patterns of subjugation and conquest? Or that the work of preserving Native American cultures (performed by Fletcher, LaFlesche, and others) would have been entirely unnecessary had they not been rendered nearly extinct in the first place?

Yet it cannot be denied that Farwell’s reverence for Native American music was genuine. Unlike other Indianist composers (Edward MacDowell comes to mind), who, as Levy writes, “overrode the Indians’ own creative agency by altering borrowed melodies or disregarding original contexts,” Farwell exhibited “ethnological scruples.” He by and large respected the primary elements of the music he adapted, preserving the key, meter, and ornamental flourishes of the original. The ethnomusicologist Tara Browner, while leveling valid criticisms against the Indianist composers, has also noted that as an advocate for Native American music, Farwell both researched the cultural context of the melodies he used and carefully identified their tribal origins. The background information provided in Fletcher’s Indian Story and Song from North America often appeared in the form of a detailed introduction to his pieces.

It’s a tricky thing—trying to come to terms with Farwell in our time. His perceived flaws provide detractors with enough justification to reject him out of hand. To them, it doesn’t matter what his music sounds like, or what part it played in the evolution of classical music in the United States. To them, Farwell is simply a white man who made a living at the expense of marginalized peoples. This, I believe, not only misrepresents the composer and his intentions, but it also uses the politics of our current moment to form loose judgments about a very distant time. We could easily continue an argument that raged in various forms for much of the 20th century, about the universality of art and its power to transcend politics. But I would also like to assert that Farwell, despite his keenest ethnographic instincts, was not an ethnographer. His principal aim was not to document Native music, and certainly not to compose it. Rather, he was writing classical music—an anti-modernist classical music, rooted in diatonic harmony and sonata form, that he felt best represented America.

Listen to The Old Man’s Love Song, or Inketunga’s Thunder Song, or any number of Farwell’s piano pieces. Seek out his post-Indianist pieces, too, the late Piano Quintet, for example, and especially The Gods of the Mountain. Reject this music, if you wish, for aesthetic reasons. But to cancel him on extra-musical grounds is, at best, to willfully ignore a pertinent chapter in American musical history and, at worst, to give in to the basest kind of anti-democratic impulse. Whether or not Farwell had the right to use the melodies that made up a portion of his work is a valid question, but it by no means should be the only one.

Listen to William Parker and William Huckaby perform The Old Man’s Love Song by Arthur Farwell:

And listen to Karl Krueger conduct the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in Farwell’s Gods of the Mountain suite:

Listen to pianist Cecile Licad perform Pawnee Horses: