A Forgotten Turner Classic

Who was George Eyser, the one-legged German-American gymnast who astounded at the Olympic Games?

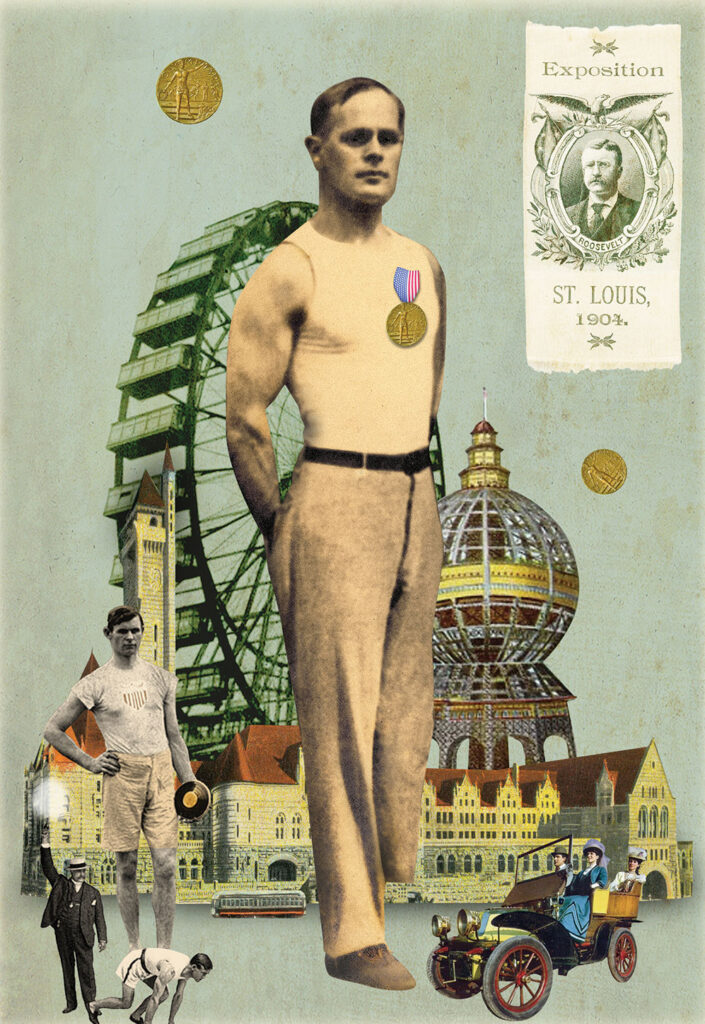

On August 16, 1918, a bookkeeper in Denver named George Eyser wrote a will. He was not married and had no children. And so it was to his only sibling, his sister Ottilie, with whom he lived in a two-story brick house at 420 Downing Street, that he bequeathed his property and possessions: money, the proceeds from an insurance policy, a gold watch and chain, a scrapbook that chronicled the nearly three decades he spent as an amateur gymnast, and his crowning glory—the six Olympic medals he won on a single October day in 1904.

One hundred and twenty years later, as we near this summer’s Paris Olympic Games, no athlete has won as many medals on a single day as Eyser did. The three golds, two silvers, and one bronze he received at the St. Louis games remain just two shy of the record for individual medals at an entire Olympiad (a record shared by swimmer Michael Phelps and gymnast Aleksandr Dityatin). And yet, it is not Eyser’s medals that most distinguish him. It is rather, as a category on Jeopardy! once put it, his “anatomical oddity”: George Eyser had a wooden leg.

That a one-legged athlete would so much as reach the Olympics is, of course, remarkable. That Eyser also won—and won and won and won and won and won—enshrined him in Olympic lore. Still, it is above all Eyser’s missing limb, not Eyser himself, that is recalled today. For all but nothing is known of the man—of his family, his disability, the 48 years he lived until his death in 1919, just months after he wrote his will. Eyser, wrote Alexis Madrigal in The Atlantic, “vanished from the history books.” Even his cause of death has, until now, remained a mystery. As one Olympics blogger asked back in 2010: “George Eyser, what happened to you?”

Way back in 1870, at a hospital in the German port city of Kiel, a doctor pondered a similar question as he wrote a report about George’s father titled “Medical examination of the state of mind of the businessman Georg Eyser.” Georg was a new patient. Thirty, Lutheran, and middle class, he had been admitted three weeks before, leaving his pregnant wife and daughter in the town of Husum, some 50 miles away on the North Sea. For two years, Georg had been decompensating, feeling at first “irascible and careless,” he told his doctor, and then distrustful, anxious, and violent. He had left his job as a merchant and declared that “he ought to die,” and then that relatives wished to kill him.

The hospital noted that one of Georg’s uncles had died “mentally ill.” And when Georg did not improve, he transferred to a mental asylum in the town of Schleswig. He was a patient there when, on August 31, 1870, his wife gave birth to a boy: Georg Ludwig Friedrich Julius Eyser.

Young Georg and his older sister, Ottilie, were soon orphaned: their father died at the Schleswig asylum in 1873, their mother five years later. Georg was 14, a foster child in the city of Lübeck, when he and his sister boarded the SS Rugia for the United States. They were off to live with a paternal uncle (John, formerly Johannes) and an aunt (John’s sister, also named Ottilie) in Denver, which had a significant German community that was home to German newspapers, churches, and schools. After moving twice, the four Eysers settled into a two-story brick house they rented in a rural neighborhood just outside the city.

John had been an educator, the principal of a German boys’ school in St. Louis, and then a teacher of astronomy. Nearing 60, he was now retired, and he paid his sister $20 a month to keep house and look after him. Ottilie already sewed, managed boarders, and raised chickens—and she would soon patent a “smoke-consuming furnace.” But she now also had to mind her brother’s clothing, medicine, food, beer, and tobacco, and raise her niece and nephew, too. In 1887, at the age of 17, George (his name now Anglicized) finished school and took a job stripping tobacco for a cigarmaker. He also joined a local gymnastics club.

The club was part of the Turner movement, founded in Germany in 1811 by an educator named Friedrich Jahn. Wanting to mold men of fine mind and body, Jahn set out to combine German culture and liberal politics with gymnastics, and he invented many of its apparatus, including the rings, pommel horse, and parallel bars. He also coined a motto for the Turners: frisch, fromm, fröhlich, frei—“fresh, pious, cheerful, free.”

Jahn’s movement flourished; by midcentury, there were hundreds of thousands of Turners. But following the defeat of the German revolutions of 1848–49, many of them emigrated to the United States, where they set up Turnvereinen, or gymnastics clubs. (Turner means “gymnast” in German. A Verein is a society or an association.) At heart, the Turnvereinen were social centers—tools of acculturation and reminders of home—its members speaking in German of the old country and bygone ideals.

Among those German transplants was George’s great-uncle Charles Eyser, who had come to the United States in 1847 at the age of 24. The youngest of eight children, he was successful in his new home, working in mining, prospecting, and contracting. He established Turnvereinen in both Iowa and Colorado, and in 1865, he was among the founding members of the Denver Turnverein.

Decades later, his great-nephew George would enroll in beginners’ classes at that club, one of many kids, instructor Jacob Schmitt recalled, with “puny limbs, round shoulders and flat chests.” Added Schmitt: “Step by step, the little ones are sent upward.”

George was 19 when, in 1889, his great-uncle Charles died of suicide by morphine. One year later, tragedy again seized the Eyser family, when John began to exhibit the same madness that had overtaken two of his uncles and his late brother Georg. Paranoid and disturbed, he developed, the press reported, “a mania for spending money,” and a medical report noted that he “was often violent” to his sister. After finding him at home one day with a bottle of poison, Ottilie took her brother to county court. On September 2, 1890, a jury declared John Eyser, age 63, “insane,” and a judge sent him to an asylum, the Jacksonville State Hospital in Illinois.

That summer, the Denver Turnverein had moved into a new home on Arapahoe Street downtown, a brown sandstone building complete with dining room, library, lodge, ballroom, bowling alley, and gym, the last equipped with electric lights and filled with every apparatus, from trapeze to pommel horse. Here the Turners trained. And in late September, 100 miles to the south in the city of Pueblo, Eyser participated for the first time in a Turner festival, one of 30 gymnasts competing in eight events—a run, a rope climb, jumps, exercises on various bars and horses. The top 10 finishers received a laurel wreath or a diploma, and Eyser finished ninth. His was a successful debut. He was an athlete on the rise. He was also a handsome young man of 20, of medium height with hooded eyes, a square chin, and brown hair high off his forehead. He spent the weekend with his fellow Turners at a banquet, a parade, and a ball.

The next year, in 1891, Eyser lost a portion of his left leg.

In 2008 and 2012, respectively, two South African amputees, the swimmer Natalie du Toit and the runner Oscar Pistorius, competed in the Olympics. Journalists looked in the historical record for other amputee Olympians and made passing mention of Eyser. I wanted to know more about him. I love sports and am disabled: back in 1990, when I was 19 years old, a bus accident broke my neck and left me hemiplegic. But Madrigal’s article in The Atlantic was right: books on gymnastics, the Turners, and the Olympics—including an account of the 1904 games published just one year later—made no mention of Eyser beyond his Olympic performance.

I thus began to search far afield for traces of Eyser, looking—in America and Germany—in censuses and city directories, auction and burial records, patient and probate files, newspaper archives and logbooks. Slowly, Eyser began to reveal himself. And yet, as for how he lost his leg, I found only vague references to “an injury” (1895, the Kansas City Daily Journal ) or “an accident” (1908, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ). (The assertion, in recent decades, that Eyser was disabled in a train accident is baseless.)

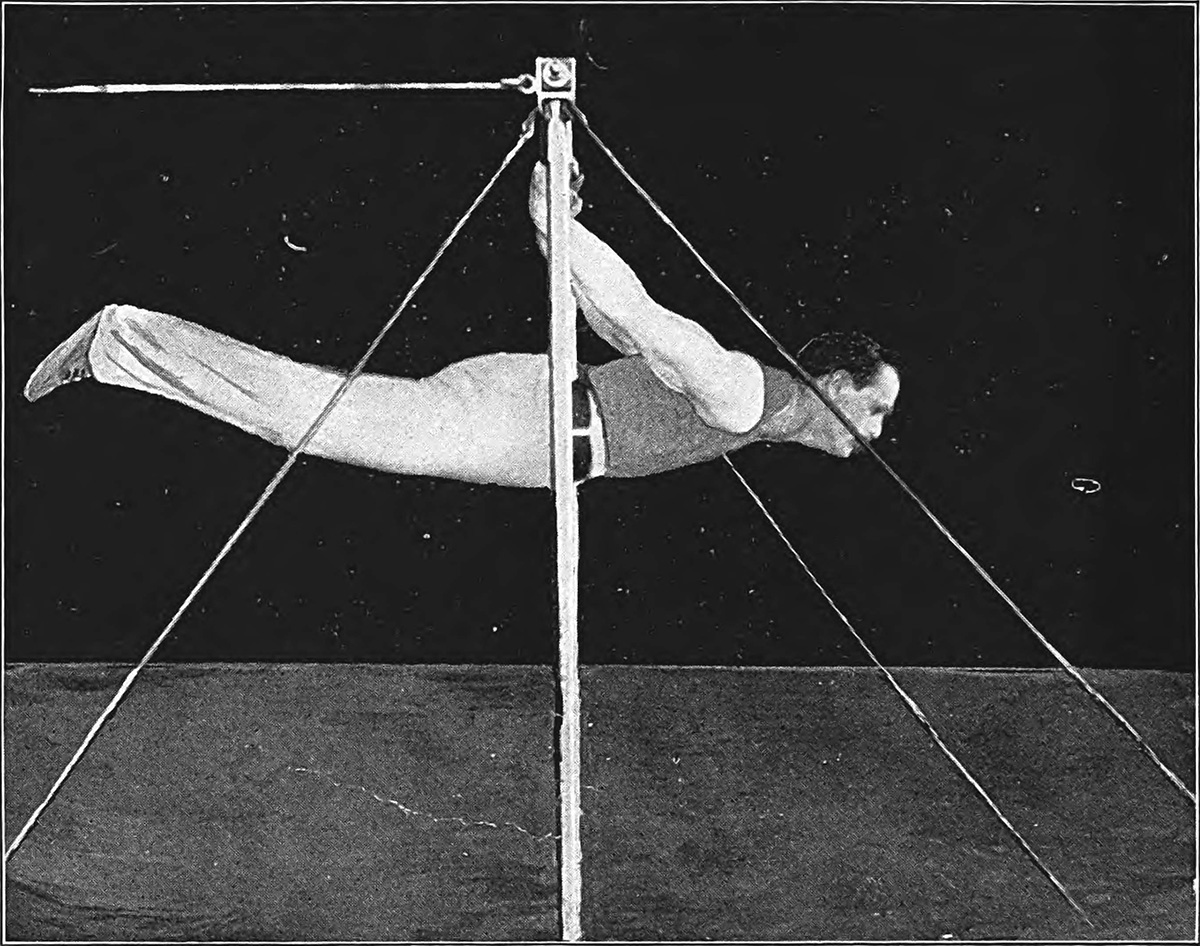

George Eyser on the horizontal bar (Western Athletics, July 1895)

I did learn when Eyser lost his leg. I had contacted a Denver man named Robert Graeber, whose grandfather Albert Graeber had competed alongside Eyser. Robert had inherited a trunk filled with paper records of his grandfather’s star career. And last year, Robert opened it for me, finding—inside an 1895 issue of Western Athletics magazine—a photo of Eyser performing a back lever on the parallel bars, his arms grabbing the bar behind his back, his prone body parallel to the ground. “Mr. Eyser,” read the photo caption, “was confined to a sick room for many months from 1891 to 1893, walking on crutches when able to be about, and finally having his left foot amputated just above the ankle.”

A subsequent surgery, I learned, amputated the leg below the knee. Eyser needed a prosthetic limb.

The U.S. Civil War had left some 60,000 young men without limbs, an epidemic of amputations that triggered, as reported in an enormous 1896 treatise on artificial limbs, “a prosthetic revolution.” The new prosthetics—jointed wood with rubber hands and feet—approximated the shape and feel of natural limbs as never before. The legs were known as “cork legs.” Eyser got one.

It is possible that Eyser was injured at work; in 1891, he was in the employ of a man named Peter Snow who was a plumber and gas fitter. It is also possible that Eyser was injured at home. In May of that year, his uncle John returned to his family after the asylum in Illinois determined that he was no longer dangerous. But perhaps he was. After John died the following February, his sister sued his estate, seeking payment for the care she had provided him. A friend of the family, a Mrs. E. Dunbar Wright, testified in the case that “he looked wild” and that she had been terrified of John Eyser until his death.

In September 1893, after two long years of rehabilitation from his injury, Eyser returned to his Turnverein and to gymnastics. There were, already, several one-legged gymnasts right there in Colorado. But they were theater acts, men with stage names like “Mr. Dare” and “Frank Melrose” and later “The Great Zenos.” And if Eyser never tried to conceal his disability—often practicing on the horse or horizontal bar without his prosthetic—neither did he wish to make use of it. He hoped to compete in spite of his disability and trained continually for a year until he had become, as that caption in Western Athletics magazine put it, “a splendid illustration of what the Turner system of physical training can do for one under adverse circumstances.” Eyser, added the magazine, “has not only a thoroughly developed muscular system, but performs many acts upon horizontal and parallel bars that would puzzle Turners possessing all members and muscles in perfect condition.”

In August 1894, 11 months after rejoining his Turnverein—and days after becoming a U.S. citizen—Eyser returned to competition at a Turnfest in Wyoming. He won and was crowned with a laurel wreath, the Cheyenne press reported, “by a number of handsome young ladies.”

Eyser was days shy of 24. He still lived with his aunt and sister. But the Turnverein was his home. There were Turner dances and picnics. There were committees, Eyser helping to raise funds toward a Christmas tree and serving refreshments at a Shrove Tuesday ball. And, of course, after work at the cigarmaker, there was the gym, Eyser training with teammates he then competed alongside at festivals across the country.

As the years passed, Eyser represented various Turnvereinen in Denver. At every stop, he won. The gymnast was a star. An Omaha paper would soon call him “one of the most remarkable athletes of his time.” And yet, for all his accomplishments, no publication profiled him. His German past and troubled family and even the basic facts of his life remained unknown; one Iowa newspaper misidentified his late father, and another in Missouri misidentified which leg he had lost.

The press alluded regularly to Eyser’s disability. He was “the crippled turner,” “the little man with the wooden foot,” “the one-legged Denver crack.” Still, newspapers focused far more on his gymnastic achievements. When, in 1895, he won an event at a national Turner meet in Kansas City, the Kansas City Daily Journal reported that Eyser

went up that big rope with long swings of his arms that never slackened or shortened until he swung his right arm over the bar and calmly drew himself up for a short rest forty-six feet above the ground. He was given a cheer that was enough to turn any man’s head, for a time, but he was impassive as a stone and came down with perfect composure and then bowed his acknowledgements to his friends.

The article noted that his routine on the horizontal bar “won equal applause.”

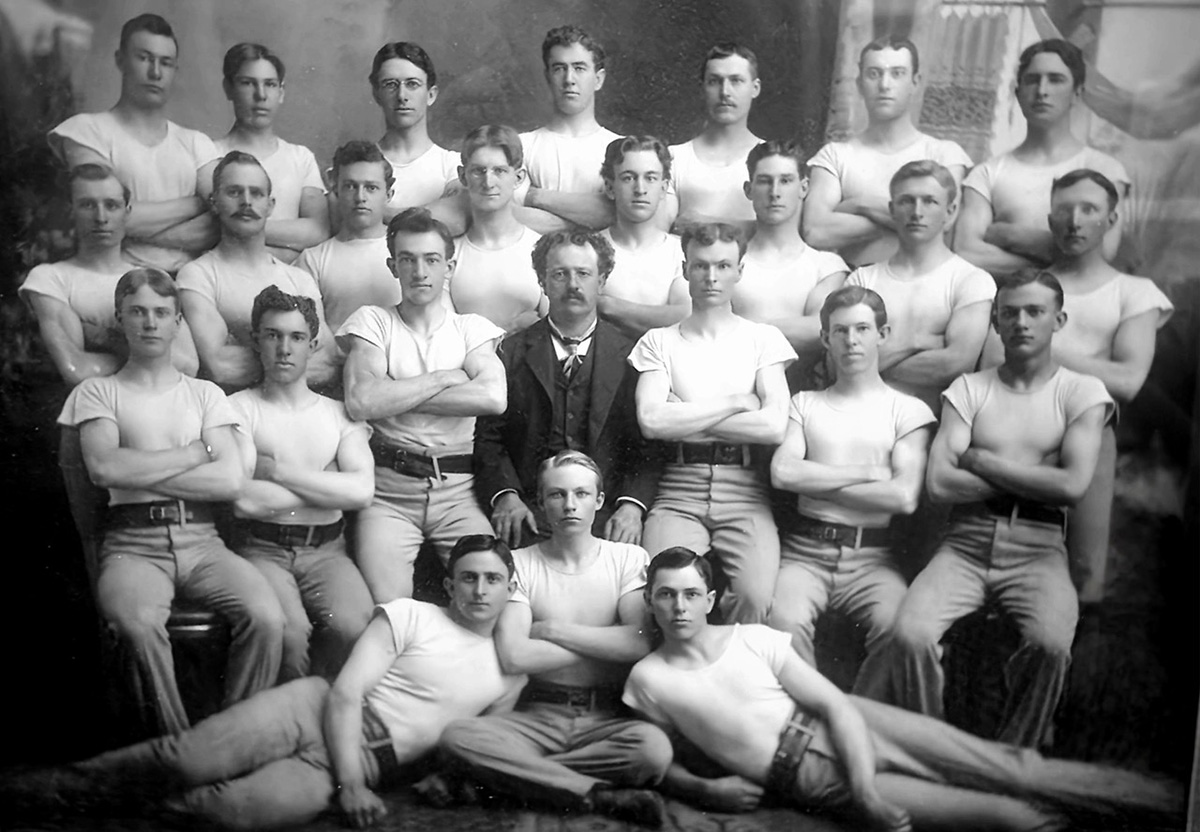

George Eyser (third row, second from left, with mustache) with his East Denver Turner teammates, 1900 (Denver Turnverein)

It was Eyser’s muscled arms that won him those events. But his legs supported him, too. He was competitive in the horse vault (which required gymnasts to run and leap over the apparatus but did not yet offer the aid of a springboard) as well as in jumping. Indeed, in June 1900, at a national Turnfest in Philadelphia, Eyser covered a full 36 feet in the hop, step, and jump. The exercise required competitors to “first land upon the same foot with which he shall have taken off,” then on the reverse foot, and then on both. If Eyser’s result was seven feet short of the victor’s, it was also, as a German paper in Baltimore, Der Deutsche Correspondent, reported, “astonishing.”

Days before that meet, Eyser and his East Denver Turner teammates had posed with their coach, Jacob Schmitt, for a team photo that would run in newspapers. The men, their white tees tucked into belted pants, stood unsmiling and with arms folded, the better to flex their biceps. All were clean shaven save Schmitt and Eyser, who wore mustaches.

Eyser had lived more than half his life in Denver. He had arrived there as a boy of 14 and was still there at 30, living with the two Ottilies. The city had been good to him. He had found community in the Turnverein, stardom in gymnastics, and steady work; in 1900, never mind his prosthetic, Eyser was a driver for a laundry and then a bookkeeper at a meatpacking company. He had money, too, having inherited almost $1,200 from the estate of his late uncle John.

Still, there was little keeping Eyser in Denver. He had no home of his own, no wife, no child. And in June 1901, he decided to move to Dayton, Ohio, where he set up a life much like the one he had left, working as a bookkeeper and joining a Turnverein, the Dayton Turngemeinde. Two years later, he moved to St. Louis, taking a bookkeeping job at a limestone quarry and teaming up with the local Turners.

The club he joined was the Concordia Turnverein. Eyser knew that in just another few months, he and his new teammates would be able to compete right there in St. Louis in what The New York Times would soon call “the greatest athletic meeting of modern times”—the 1904 Olympics.

The modern rebirth of the ancient Olympic games had taken place in Athens in 1896. A second Olympiad had followed in Paris in 1900. Chicago was to host the third in 1904, but the games were moved to St. Louis to coincide with the World’s Fair. Since the fair would last seven months, the Olympic games were stretched from July through November, with gymnastics slated for both July and October. It was thus difficult for some foreigners to participate. Indeed, although a dozen countries would be represented in St. Louis, 523 of the 630 athletes set to compete in the 1904 Olympics were from the United States. Years later, some critics would cite that figure to disparage the competition. But the previous Olympics were much the same: in Athens, for example, 230 of the 311 athletes were Greek. Still, the gymnastics competition that summer of 1904 promised to be stiff, with Germany—the other gymnastics powerhouse besides the United States—sending seven gymnasts to St. Louis to take on 112 American gymnasts, Eyser among them.

Eyser had been a gymnast for 14 years, a star the previous 10. But he was unknown to St. Louis. And when, on the first of July, competition began with exercises on the horizontal and parallel bars and the horse, the gymnast, according to The St. Louis Republic, “attracted much attention from the fact that he [had] only one leg.” The Westliche Post added that there was “general regret when he stepped up to the apparatus.”

Eyser did not react. He simply performed. The Mississippi Blätter ran a photograph of him on the high bar in mid-kip, his hips flexed, legs extended, as he prepared to cast to a handstand. And there, at World’s Fair Stadium—a newly constructed concrete oval and grandstand that was, The New York Times gushed, “as nearly as possible a counterpart of the ancient stadium at Olympia”—the gymnast won the crowd over. As the Westliche Post reported, the regret generated by his cork leg “immediately turned into loud enthusiasm … which was expressed in never-ending applause.”

And yet, Eyser had no chance of winning this first Olympics competition; it required the gymnasts to compete in various track and field events. The next day, against a field of 117 others, Eyser finished 76th in the shot put and dead last in both the long jump and 100-yard dash, running the race in 15.4 seconds. That a one-legged man had finished the race only 4.8 seconds behind the winner (a Turner from Indianapolis) was remarkable. But Eyser had nonetheless dropped far from medal contention. He would have to wait until late October for that second Olympics competition—one that would not involve any track and field components—and he trained for it at his Turnverein, a dozen or so blocks from his apartment on Ohio Avenue.

As summer turned to fall, the Olympics were generating great excitement, “a vigorous spectacle suited to an energetic and confident nation,” writes the sports historian George Matthews. World’s Fair Park, on the grounds of Washington University, hosted everything from archery and roque (an American variant of croquet) to weightlifting and tug of war. And on Friday, October 28, crowds filed into its concrete grandstand to watch Eyser and his fellow local Turners take on the best.

Eyser was slated to compete in five events and paid a $1 entrance fee for each. Four of the events primarily involved the upper body: the rope climb, parallel bars, horizontal bar, and pommel horse. The fifth, the horse vault, required legwork, the gymnast needing to hurtle himself over the horse and land squarely on two feet. In addition, Eyser would be up for a sixth medal based on a combined score of all events save the rope climb.

It was a lovely fall day, the temperature rising to 64 degrees. And at one p.m., Eyser stood in his belted pants and shirt, ready at the age of 34 to seize the great moment of his career.

The competition called for the gymnasts to perform on each apparatus three times. The parallel bars were first, and Eyser pulled himself up onto them under the watch of three judges who would score his routine (from zero to five) for difficulty, form, and “beauty.” Eyser won gold, edging out Anton Heida, a star Czech-born Turner from Philadelphia, by a single point, 44–43.

Next was the horse vault. Two years prior, Heida had been the national vault champion. For Eyser, it was the most difficult apparatus; hurtling aside, he had to land three times. This he did in a manner, the judges ruled, equal to Heida. The men tied, each winning gold.

Heida then bested Eyser in the two events that followed—the pommel horse and horizontal bar. Still, Eyser was brilliant, winning a silver in the former and a bronze in the latter. Last was the rope climb. The gymnasts started their 25-foot climb with the shot of a pistol. Eyser was first to the top, striking the bell that marked the end of his climb after seven seconds flat. It had been a brilliant performance: five medals in five events. And Eyser’s combined scores in the first four events won him silver in the combined “all-round” competition. Heida may have won gold, but everyone in attendance knew that Eyser had done what he had done on a wooden leg. The Westliche Post referred to the competition as “the ‘Eyser’ festival.”

History would not celebrate the 1904 Olympic Games. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the International Olympic Committee, was livid that they had been moved from Chicago to St. Louis, and he would later write in a 1931 memoir that “the St. Louis Games were completely lacking in attraction.” But in truth, despite some notable problems (among them a marathon marred by poor officiating, cheating, and a lack of drinking water), the 1904 games—the first to award gold, silver, and bronze medals to the top three finishers—were a triumph. Organized by the Amateur Athletic Union, the games drew crowds, press, and public support. They introduced new Olympic events (including boxing and the decathlon), set world records, and saw barriers broken—George Poage and Joseph Stadler, for example, becoming the first African Americans to compete (and medal) in the Olympics. They also featured a one-legged gymnast who won six medals.

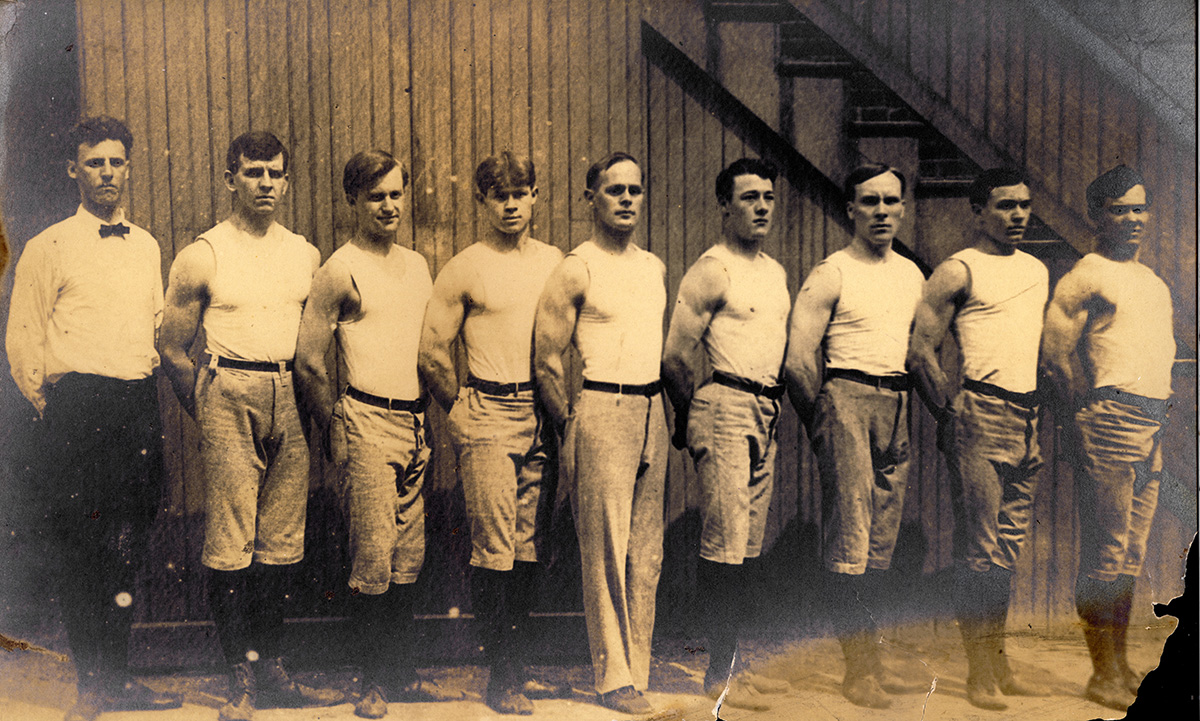

Eyser’s historic day did not change his life. He continued bookkeeping at the quarry and training at the Turnverein. But he was now the unquestioned star of his Concordia team—its representative on a St. Louis gymnastics committee and at the center of nearly every team portrait. So Eyser was in a photograph taken in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1908, his left pantleg visibly empty below the knee.

The men had traveled to Germany along with some 1,000 American Turners for a gargantuan international meet, sailing in late June from Baltimore on the German ocean liner SS Main. Twenty-four years had passed since Eyser had left Germany, 13 since Germany had accused him of not showing for military service and of leaving the country without the required permit. But Eyser was welcomed back. Indeed, as he and his teammates trained in Wiesbaden and partook in marches and drills and massive exhibitions—including one that featured 14,000 men in 35 columns doing calisthenics—it was the American Turners in particular who received, in the words of the American Physical Education Review, “the cream of the people’s enthusiasm”—cheers and flowers hurled at them from windows and sidewalks.

The competition was no less grand. Held over four days in July, it drew roughly 100,000 daily visitors, among them Prince Oscar, son of Emperor Wilhelm II. Fans filled tented pavilions and grandstands, looking out at 50 parallel bars, 44 horses, and 16 horizontal bars, all simultaneously in use. Here, amid thousands of gymnasts, Eyser and his Concordia teammates stood out: during one contest with a field of 2,298 entrants, they performed “nearly perfect” routines, according to the American Physical Education Review, and captured six of the 20 victories by American gymnasts.

George Eyser (center) with the Concordia Turnverein Gymnastic Team at the International Turnfest in Frankfurt, Germany, June 1908 (Missouri History Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

For all that, the festival was about much more than competition. It was, as the American Physical Education Review put it, “an extension course in physical, vocal, social and ethical training.” Away from the gym, the Turners came together in song and dance and discussion, and shared meals and attended lectures about competition and work. The festival was thus true to the vision of Friedrich Jahn, founder of the Turner movement, and Eyser and his teammates posed with an American flag in front of a bust of Jahn, a photograph preserving them in suit and bowtie. After an extended tour of Germany, the Turners returned home.

Back in St. Louis, Eyser grew restless. He switched jobs at the quarry from bookkeeper to cashier, and he moved, renting a room in a single-family brick house in Tower Grove South, a pleasant neighborhood beside a large park. Eyser continued to perform, traveling to Cincinnati for a big Turnfest in 1909. The local press reported that he still possessed, months shy of 40, “the same agility as other Turners.” But he had all but stopped competing in June 1914, when, at the age of 43, he participated at a local meet with his Concordia teammates.

Weeks later, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand triggered the start of World War I, and anti-German feeling spread across the United States. Eyser left St. Louis the next summer to be with his sister and aunt in Denver, where he found work as a bookkeeper. The large German community that he now rejoined was desperate to make clear its loyalty to the United States; a 1916 editorial in the German-language Denver Colorado Herold declared itself “Für Amerika Zunächst”—“For America first.” No less desperate, a large number of Denver Turners left their Turnverein. The club was soon broke, and in August 1916, its grand home was repossessed. When Eyser subsequently began to coach, he did so not at a Turnverein but at a YMCA. And when, in late 1916, he wished to compete, he entered not a Turner meet but the Amateur Athletic Union gymnastic championship of Southern California. Forty-six years old, he won it.

Eyser remained in California a few months into early 1917, living in the Oviatt Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. Still, three newspaper ads he placed looking for bookkeeping work went for naught. And Denver soon beckoned him home when, in mid-March, his Aunt Ottilie died. Eyser moved back in with his sister.

The next month, the United States declared war on Germany. Anti–German-American sentiment was aflame, and in Denver, German salespeople were boycotted, German books were burned, and a school superintendent with suspected German sympathies was tarred and feathered. Weeks after his nation declared war, Eyser performed for a final time, at an exhibition at his YMCA, lifting himself up onto parallel and horizontal bars.

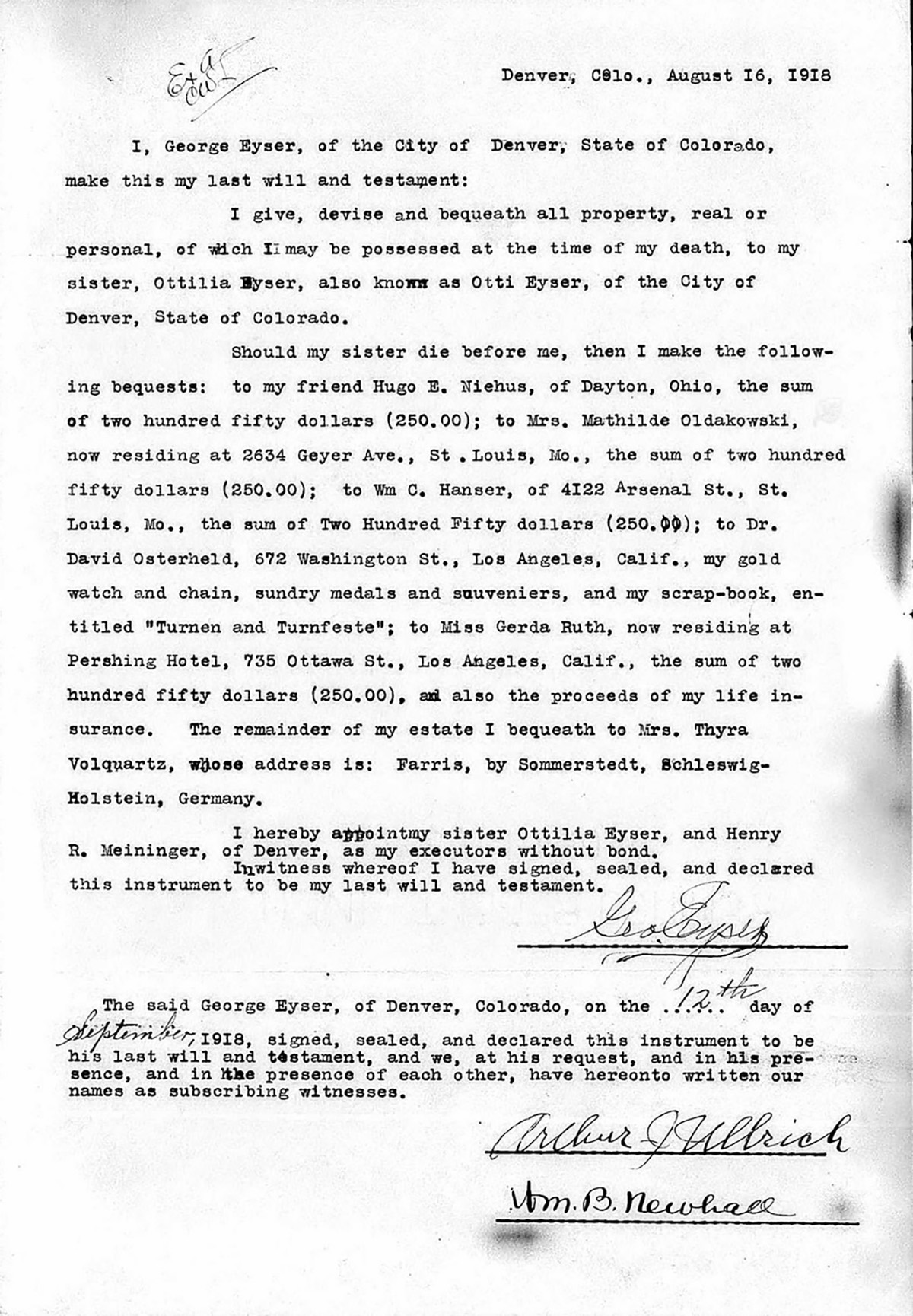

George Eyser’s will, signed just months before he died (County Court of the City & County of Denver via Ancestry)

The following summer, Eyser wrote a will, bequeathing all he owned—an estate valued at $2,001—to his sister and housemate, Ottilie. The will, a single typed page, stipulated that if Ottilie predeceased him, his possessions would instead go to six friends who lived in the various places he had previously called home: Los Angeles, Dayton, St. Louis, Germany. On September 12, 1918, in the presence of two witnesses, Eyser signed his will. He was 48 years old.

The calendar turned to 1919. There was a feeling of revival in the air, the war having finally ended in November. But at 11 p.m. on March 6, 1919, inside a small brick house in south-central Denver, George Eyser raised a pistol to his left breast and pulled the trigger. He died 10 minutes later.

The next day, The Denver Post carried news of the suicide—six sentences on the bottom of page 11. The notice made no mention of Eyser’s having been a gymnast. It relayed only his age (which it got wrong), his address, profession, and cause of death, as well as the names of the coroner and undertaker. It further asserted that Eyser had been sick. “Eyser was in poor health,” it read, “and this is thought responsible for his action.”

If Eyser had indeed been sick, he had become so only recently—for his will had accounted for the possibility that his (healthy) sister might predecease him. It is thus logical to wonder whether the mental illness that had so long seized his family had finally come for him. Indeed, though Eyser was known for a physical disability, mental illness had more profoundly shaped his life.

Four days after his suicide, at a cemetery on the South Platte River some four miles downstream of Denver, Eyser was cremated. The urn containing his ashes was taken to Hofmann Mortuary in central Denver for a private ceremony at two in the afternoon.

Eyser had bought burial plots for both his aunt and his sister in Block 21 of Fairmount Cemetery in east Denver, and in 1946, the cremated remains of his sister Ottilie would be interred there. But there is no record that Eyser’s ashes were too. After his urn was taken to the Fairmount Cemetery office on March 12, the record goes blank. There is no indication that his sister, or anyone else, picked it up. In such cases, the mortuary generally retained possession of the deceased’s remains. Today, Hofmann Mortuary is defunct, its records lost. It is not known whether Eyser’s remains were buried and, if so, where.

Also unknown are the whereabouts of Eyser’s scrapbook and most of his Olympic medals. His gold for the rope climb and his bronze for the horizontal bars did turn up in recent years at auction, and I traced their provenance back some 40 years to a long-shuttered thrift shop in Covina, California. How the medals got there can be surmised: the shop was a little more than 30 miles from Long Beach, where Eyser’s sister lived during the last 15 years of her life.

Eyser died 105 years ago. Those who knew him have died as well, and none of the descendants of the friends he named in his will have even heard of him. Nor have Eyser’s only living relatives—distant cousins in Denmark. In the absence of information, people see what they wish to in Eyser: one sportswriter told The Wall Street Journal that the success of a one-legged gymnast was proof that the 1904 Olympic Games were “best forgotten.” But the opposite is true: 120 years ago, a man named George Ludwig Friedrich Julius Eyser did something remarkable, and that is best remembered.