A Jane Austen Kind of Guy

I get it that women find my affinity for their writer intrusive, but her world has much to offer men, too

I was sitting there at MLA, the annual convention of the Modern Language Association, interviewing for an academic job. This was about 10 years ago. The conversation had been going on for a while (it was a big committee) when finally the dean in charge, by way of drawing things to a close, posed a question that she must have been dying to ask for a long time. Glancing down once more at my CV—I had written a dissertation on The Novel of Community from Austen to Modernism, published a book titled Jane Austen and the Romantic Poets, and was planning a study called “Friendship: A Cultural History from Jane Austen to Jennifer Aniston”—she looked up and said, “So what’s with you and Jane Austen?”

Meaning, of course, “You’re a guy. What’s with you and Jane Austen?” Or to be more precise, “We figured you must be gay, but since it turns out you’re not” (I had mentioned my wife), “what’s with you and Jane Austen?”

It’s a question that would never have been asked of a woman, needless to say, but I suspect it wouldn’t even have been asked of me had I specialized in any other female author. “What’s with you and George Eliot?” “What’s with you and Virginia Woolf?”: somehow those questions don’t possess the same resonance, the same inevitability. But the strangeness, the effrontery, of a heterosexual man who reads Jane Austen is so obvious, so much a commonplace, that the dean could take it for granted as the unstated premise of her question. She knew that I would acknowledge the circumstance as something that I might be called upon to defend.

And I did, because I had, more than once. Years before, in the depths of graduate school, I had fallen into conversation with a high school teacher while traversing the Columbia campus. It was the Sunday morning after a heavy snowfall; we were the only ones trudging across the deserted plaza. (I think she was there for some kind of workshop.) The conversation had been perking along until she asked me whom I studied. “Jane Austen,” I said. “But you’re a man!” she exclaimed, with a look of injured bewilderment. It was like I had done something to her. “But you’re a man!”—as if that was all that needed to be said.

A couple of years later, I found myself home for a family meal: always a fraught situation, especially with three adult children—or two adult children and one, me, by far the youngest, still trying to establish his adulthood. At one point my scientist father, attempting to relate to my interests but a few years behind the curve, referred to James Joyce (I have no idea how this even came up) as my “literary hero.”

“No he’s not!” I burst out, regressing instantly about a dozen years.

“Yeah, so who is?” my big brother said.

“Jane Austen!” I replied, with juvenile defiance.

“Get out!” he shot back. Like, there I was again, just being my usual difficult self. He didn’t know much about books, but he knew enough to know that my answer was ridiculous.

So that interview was not the first time I had had to defend my love of Jane Austen. Nor would it be the last, especially, some five years later, after I published A Jane Austen Education, a memoir of my encounter with the author during those very years in graduate school, and of the way she helped me to become an adult. Every time I explained what the book was about—at a party, or to the friend of a friend—there was always a little pause as they tried to work it out, tried to do the math. Men, in particular, would get this look in their eyes, as if to say, “What’s wrong with you, dude?” And whenever I did a reading or went on the radio, I always felt a subtext, a question hanging over the proceedings.

Sometimes the text was not even “sub.” One host, on a local public radio program, patrolled the gender lines relentlessly throughout our conversation. “I know there are many Jane Austen fans listening, probably women,” she said right off the bat. “I’m curious about the men who may be listening, who may be thinking, ‘Eh, this guy’s a weenie. I don’t care what he says.’ ” So already she was furnishing a script, a gendered script, for listeners to follow.

Which they did. The very first caller criticized the book, which I’m pretty sure she hadn’t read, for not discussing the fact that women in Jane Austen’s day were dependent on men for financial security and therefore occupied a subordinate social position. You’re right, I said, they were and they did, but there are also lots of other things to talk about in Austen’s work, most of which apply to men and women equally—like love, and friendship, and growing up, and keeping your eyes open—and those are the things I discuss in my book. But that clearly didn’t cut much ice with her.

In all this, I think, we can distinguish two impulses. One is a desire to exclude men from the sphere of Austen’s readers—or at least to mark them as resident aliens rather than natural-born citizens and thus to claim Austen as the exclusive property of a female readership.

The other impulse rejects the idea that men—that real men—would want to enter Austen’s world to begin with. We still have trouble with gender, no matter what advances we have made. We still think in terms of “acting gay,” which often, to a first approximation, means acting female: dressing colorfully, or being into musical theater—or loving Jane Austen. Those are all fine, if you actually are gay. But they’re not fine if you aren’t. Straight men are still supposed to act the way they’ve always been expected to (just as straight women are). So for a straight man to express a devotion to Jane Austen’s novels is to fall short of the gender performance that society expects of him. This will almost invariably arouse anxiety in other people, who will feel entitled, like the dean or the radio host, to police the violation.

But why Jane Austen, of all female authors? Why is she the one we so identify not with femaleness but with femininity? The answer goes, I believe, to both the way her novels are constructed and the way they’ve been received. That is, to the nature of Austen’s world in both senses: the world of her characters and the world of her readers, the world she made in her work and the world, the community, we’ve made around it.

Compare Jane Austen’s novels with those of Eliot or Woolf or Charlotte or Emily Brontë and you find that hers are centered, far more than the others’, on feminized spaces. Which means, to start with, on domestic ones. Such environments are not necessarily feminine—think of Wuthering Heights—but in Austen, they almost invariably are: the space that the heroine rules in Emma, the one from which Mr. Bennet withdraws in Pride and Prejudice, and so forth. The activities that happen there—tea, conversation, musical performance, needlework—are female ones, as well.

But Austen’s feminine spaces are also those created between women. Marriage, the establishment of a relationship between a man and a woman, is always her endpoint, but what her stories mainly move through are female relationships: between sisters like the Dashwoods in Sense and Sensibility, the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice, or the Elliots in Persuasion; between friends like Catherine and Isabella or Catherine and Eleanor in Northanger Abbey; between young women and older ones like the heroine and Mrs. Weston in Emma or Anne and Lady Russell in Persuasion. That’s where most of the conversations happen, where the feelings are worked out. Men may be the topic, but it’s women who do the talking.

Austen’s novels have also been received, especially in recent years, as feminine in a more stereotypical sense: as romance novels in the contemporary meaning of the term, chick lit in its purest form. The movies do this, and so does the fan fiction. But her stories aren’t primarily about romance. Love comes only at the end—her heroines must grow up first—and when it does, it doesn’t look like Cupid’s arrow. Love, for Austen, is a slow outgrowth of friendship. It’s something you have to prepare yourself for, not something that magically happens to you.

But the movies—the major way that people are exposed to Austen’s work today, and certainly the leading factor in creating her contemporary image—never stand for that. She is always Brontëized, always turned into the exponent of grand and unquenchable passion. The music swells, the handsome actors and beautiful actresses—always so much better-looking than the characters are in the books—lock lips with hungry urgency. So what’s scrubbed from her stories is not only everything else they’re about, but Austen’s own violations of gender performance. Jane Austen, as anyone who has read the novels (and still more, the letters) knows, was not a good girl. She was cool, sharp, sometimes bawdy, sometimes cruel. Her novels can be gloomy, even sour. In her own life, she chose art over marriage. Yet all this has been airbrushed from the picture.

Still, the desire to exclude men from the world of Austen’s readers is not entirely an artifact of what she has become at the hands of popular culture. It originates not only in the novels’ focus on feminine spaces and relationships, but also in the way that female desire circulates in and through them. And here we’ll see how Austen’s worlds—her characters’ and her readers’—have a tendency to mirror each other, and also how they have a way of blurring together.

We can start by noting that although her novels are centrally concerned with female desire—the desire for a “single man in possession of a good fortune”—that desire is largely suppressed. Or at least, its sexual component is: one reason, I think, the emphasis often falls precisely on that good fortune, on “his beautiful grounds at Pemberley,” as Elizabeth Bennet so cheekily puts it, rather than his beautiful person. That suppression is part of what people mean when they say, not quite correctly, there is no sex in Jane Austen. It certainly is a highly sublimated world. There’s a kind of chaste modesty about the way Catherine expresses her attraction for Henry in Northanger Abbey, or Elinor for Edward in Sense and Sensibility. Jane Bennet gets in trouble for exactly this reason. Fanny, in Mansfield Park, conceals any trace of her desire, and Emma doesn’t even know she has it. Think of the embarrassment of Harriet Smith’s pathetically naked needs in Emma, or the scandal of Henry Crawford’s intention to arouse those of Fanny. The young women who refuse to adhere to the code are Austen’s bad girls—Marianne Dashwood, Lydia Bennet, Mary Crawford—and they get punished for it. Austen’s world puts young women in the paradoxical, the impossible situation of being asked to think of marriage all the time, of sex never.

This isn’t just a matter of the age that Austen lived in—though I didn’t understand as much until I started spending time with other Austen authors. At the Printers Row Lit Fest in Chicago, the year after A Jane Austen Education came out, I was one of six; at the Decatur Book Festival in Georgia a couple of months later, I was one of 16. Almost all, needless to say, were women.

We had two panels at Printers Row. The first, which it won’t surprise you to discover I was not invited to join, was titled “Jane Austen’s Men: What Makes Them Sexy.” I’m obviously way too innocent, but that was the first time it occurred to me that a large part of the experience of reading Jane Austen, for women or at least for many women, is defined by exactly that question.

I should explain in my defense that I am old enough, just barely, to have grown up in a world, like Austen’s (and certainly this was also because I was raised in a religious community), where women didn’t have desires. Or so, at least, the story went. “Men get married to have sex; women endure sex for the sake of marriage”: that’s the kind of thing you heard. The notion is absurd, of course, and I did figure out just how absurd before I was very old, but there must’ve been enough residual naïveté for me to have missed what’s going on when it comes to Austen. Or perhaps I simply hadn’t thought enough about what’s going on for female readers, at least not until that day in Chicago.

What occurred to me, as I listened to the panel, was that Austen’s world does function as an arena for the unbridled expression of female desire, but that desire is the reader’s. The impulses that her heroines must conceal or repress, out in the intensely public spaces of her novels, her readers are encouraged to indulge in the privacy, as it were, of their bedrooms. And that indulgence is all the greater precisely because it is denied to the heroines. More demonstrative characters would get between the reader and the hero, would take up all the emotional space. Readerly imagination, as is often said, is incited by what is omitted. Austen’s readers, indeed, can be said to desire her heroes, at least some of the time, even more than do her heroines, because they often get there first. They have no ambivalence about Mr. Darcy, no ignorance about their feelings for Mr. Knightley, no indifference to Colonel Brandon. They are only waiting, as it were, for the heroines to catch up.

People sometimes ask me what I think of all the adaptations and spinoffs—the movies, the zombies, and so forth—and what I think Jane Austen would have thought. I say that my feelings are mixed (it depends which ones we’re talking about), and that Austen’s probably would’ve been as well, but I recognize that such responses are entirely appropriate. We don’t do this kind of thing with Dickens or Mark Twain, though they’re equally beloved. We don’t do it with Conrad or Joyce, though they’re equally great. There is something in Austen that inspires us, that encourages us, to make our imaginative lives, our fantasy lives, continuous with hers, to dream, with her, her dreams. It is no coincidence that her own writing began in an intensely imaginative, deliriously playful engagement with the novels she was reading—those parodies and knockoffs that she wrote when she was young, and of which the greatest example is Northanger Abbey itself. Austen wrote back to her favorite books, so it makes perfect sense that she constructed her own so as to invite us to do the same: to put ourselves in her place and therefore, as any author must, in the place of her characters—as the writers of the fan fiction do when they seek to imagine the minds of Elizabeth Bennet or Anne Elliot and as so many of her readers do when they think about what makes her men so sexy.

So what does make her men so sexy? What does it take to become a hero in Austen’s world? There is nothing sexier in Jane Austen, said one of the authors on the panel, than Mr. Darcy reading a book, because he’s doing exactly what the reader is. A second person said that the sexiest activity Austen’s heroes engage in is writing—another instance of the hero’s being desired because he is acting as the reader might. Others cited the heroes’ amiability, their integrity, their willingness to put aside class differences for the sake of love, their reluctance to speak and willingness to listen, their sense of humor (in the case of Henry Tilney), and their willingness to admit when they’re wrong.

All these are moral or mental qualities, not physical ones. Is that because the novel isn’t a visual medium, because we cannot see the heroes? But what of the Brontë men (Brontësaurases?), of Heathcliff and Rochester, as virile as they come? Most of Austen’s heroes are feminized or emasculated: Edward Ferrars, in Sense and Sensibility, who is weak; Colonel Brandon, in the same novel, who is aging and ailing; Edmund Bertram, in Mansfield Park, who is a dependent younger son; Henry Tilney, in Northanger Abbey, whom one panelist referred to as a metrosexual. So many of the qualities the panel cited are about a hero’s “willingness” to accommodate himself to the heroine, to assume the shape of her desire. To be a man in Austen’s world is to discover that the tables have been turned on you, that you’ve become the object of desire, not its agent.

To much of this, of course, there is one large exception. Or should I say, one “fine, tall” exception. There are seven Austen heroes, counting the two in Sense and Sensibility, but a good half of the panel discussion, and of the audience’s questions afterward, were devoted to just one. And you know who. Just as Pride and Prejudice is the book of books for Austen lovers—my impression is that the lion’s share of the fan fiction consists of variations on and sequels to that single novel—so is Mr. Darcy the hero of heroes.

Why? Surely because he’s not the least bit feminized. He’s tall, he’s good-looking, he’s arrogant, he’s commanding. Just as Austen’s heroines are so often not the most beautiful young women in their novels (Elizabeth Bennet is set against her sister Jane, Fanny Price against Mary Crawford, Anne Elliot against the Musgrove sisters), so are her heroes often juxtaposed to more stereotypically masculine figures—Willoughby, Captain Tilney, Henry Crawford. The heroes also usually aren’t the richest young men in their novels, either: they aren’t Robert Ferrars or Mr. Rushworth or William Walter Elliot. But not in Pride and Prejudice. Pride and Prejudice is everybody’s favorite—even, I’d venture to say, of those who admire some of the later novels more—because Austen gives us everything we want. It is “light, and bright, and sparkling,” as she crowed in a letter: the funniest, the wittiest, the best lines, the most perfect plot, the most lovable heroine, the most beautiful estate. And a hero who is not only all the things I said before, but the wealthiest and most well-born man in sight. In Pride and Prejudice, the wish fulfillment is complete.

But something more is going on, as well. Mr. Darcy’s deepest appeal, it seems—to put it crudely—is that he’s an asshole: an asshole whom the heroine reforms. He is the masculine principle tamed. What does it mean to say that he’s an asshole? “Tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me”: Darcy wounds the heroine’s sexual pride. He pronounces her unworthy of desire. And Elizabeth’s triumph comes—and with it, the reader’s—when he is made to recant and repent: “One of the handsomest women of my acquaintance.” The allure of Mr. Darcy—his reading and writing and even the glorious Pemberley notwithstanding—is essentially a sexual one.

I feel bad for the other heroes. To speak of Austen’s world—the totality of the novels plus the imaginative sphere that her readers have constructed on top of them—is to recognize that the borders between the novels are porous. It’s all one big extended family. We compare the heroes with one another because in some sense they all occupy the same space. Edmund isn’t just competing with Henry Crawford; he’s competing with Mr. Darcy, too: not for Fanny’s affections, but for ours. Among the heroines, Elizabeth and Fanny and Emma each have their partisans, but who among the heroes can stand up to Mr. Darcy? His figure dominates the whole of Austen’s world.

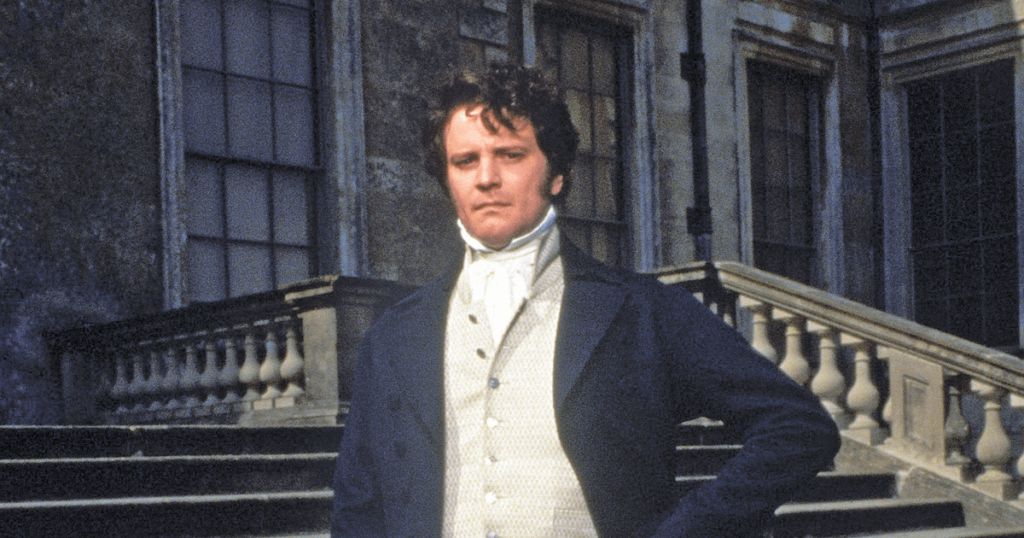

As if the deck weren’t stacked enough, Mr. Darcy now has something else to recommend him. He isn’t merely Mr. Darcy anymore. He’s now that hybrid creature whom I’ve come to think of as Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy. I have yet to meet a woman who is not in love with Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy. Not Colin Firth, not Mr. Darcy, Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy. My Orthodox sister, who never talks about sex, never shows any interest in celebrities, and hardly ever watches television, starts to look uncomfortable when someone mentions Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy. I taught a course some years ago in the literature of friendship. Fifteen women and three men. There were a few movies on the syllabus, so I’d arrange for screenings after hours. The day I showed When Harry Met Sally …, nobody showed up. When, the following day, I asked my students why, they told me that they all had DVD collections of their own.

“Really?” I said. “And they all include When Harry Met Sally …?”

“Yeah,” they said.

“Okay,” I said, “so what else do they all include?”

Pretty much every single woman looked at me like I was dense and said, “The Colin Firth Pride and Prejudice.”

It was Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy who ignited the Jane Austen frenzy of recent decades. She was popular before, but not like that. One of the authors at Decatur told me that she had been inspired to write fan fiction by the Colin Firth Pride and Prejudice, and she knew the same was true of many others. Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy—Colin Firth plunging into the water in his skivvies to cool his inflamed passion—allowed the desire for Mr. Darcy to assume a more explicitly sexual form. How sexy was Mr. Darcy before Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy? How sexy was Colin Firth? Character and actor now seem to constitute each other, in the popular mind, and Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy appears to have become a denizen of Austen’s world in his own right.

And isn’t it interesting that it’s the “Colin Firth” Pride and Prejudice? Whenever I’m talking with someone about the Colin Firth Pride and Prejudice and I mention Jennifer Ehle, they invariably say, “Who’s Jennifer Ehle?” And I say, “she’s the star of the ‘Colin Firth’ Pride and Prejudice.” Is there another movie that’s identified with an actor other than the lead? None that I can think of—except the Laurence Olivier Pride and Prejudice. What does the erasure of Jennifer Ehle or Greer Garson signify if not, once again, the desire of the implied reader or viewer—the implied female reader or viewer—to experience an unmediated relationship with Mr. Darcy: or in plainer language, to have him all to herself?

So if the world of Austen fandom is one of female heterosexual desire—if that, beneath the other interests that her fiction offers, is the principal point of communion—then it’s perfectly coherent that the presence of a man in that world, especially a straight man, would be felt as an intrusion, or at best, a pleasant curiosity. Loving Jane Austen appears to have become a female bonding ritual. I do not say that with derogatory intent. I’ve found it touching to discover that the love of Austen is often passed from generation to generation. People bring their daughters to the readings and the book groups and the fan conventions. When I ask, while signing someone’s copy, how long she has been an Austen fan, the reply is often something like, “Since I was 16. My mother gave me Pride and Prejudice”; or, “Not till after college; a friend turned me on to her.” The presence of a man in such a context is only going to generate unwanted static. No one wants a guy there any more than they do at a bachelorette party.

This is, as it happens—another way that Austen’s worlds mirror each other—something like the situation of the men within the novels. It isn’t that they aren’t welcome, but they also come as alien outsiders into those feminine spaces. Lone wolves, as it were, roving out beyond the borders of the domestic, off in the dark somewhere, doing their mysterious business with horses and guns, reappearing with maddening irregularity. Free agents of unguessable intent, they always seem to pop up when you least expect them, and to be absent when you most want to have them around. Indeed, it has been suggested to me more than once that this is a central part of their fascination for the female reader.

It is not surprising, given all this, not only that a man who sought to enter Austen’s world would tend to find his masculinity questioned, but also that very few men would want to do so. Which is exactly the position that I found myself in at the age of 26, when the story in my book begins. I didn’t know anything about Jane Austen, except that she was the last person I would ever want to read. Feminine, trivial, nothing but romantic fairy tales: I had absorbed all the stereotypes, and I wanted manlier stuff. What I came to learn over the next six years, during my Jane Austen education, was not only how to be a better person, but how to be a better man.

As for the dean’s question, that day at MLA, this is what I replied. “I don’t know,” I said, “sometimes I just feel like everything I know about life I learned by reading Jane Austen.” Which means her novels enabled me to become a hero, too—if only, as David Copperfield would say, the hero of my own life.