A Life in Letters

A decades-long correspondence with the Italian writer Arturo Vivante covered it all: hardship, love, and the endurance of art

In the late 1950s, Arturo Vivante, an Italian doctor living in Rome, began publishing short stories in The New Yorker. I was a young writer at the time, studying with Andrew Lytle at the University of Florida. Vivante’s stories, written in English, seemed so alive and true. They created in me an energy that sent me back to my dorm room to write late into the night.

By the time I finished a year of graduate school, I had sold a story to Mademoiselle, and in 1962, I took up residence with my husband, Joe, and new baby daughter at Stanford, where I had been selected to be a Wallace Stegner Fiction Fellow. The first two stories I wrote in Stegner’s workshop were brazenly lifted from real life. “A Daughter of My Own” depicted the time when my mother came to “help out” with our baby and ended up intruding almost violently into the life of our family. “We Know That Your Hearts Are Heavy” was about the funeral of my father’s brother, where, when the coffin was brought into the synagogue, I heard for the first time my father sobbing, almost choking, with grief. To my astonishment, I sold both stories, the first to Redbook, the second to The New Yorker. What luck!

I knew I had revealed too many secrets, but I took courage from what Vivante dared to do. His story “The Wide Sleeping Bag,” published in The New Yorker in 1958, begins:

Sometimes I wish things so intensely they happen. But the circumstances through which they come about, the ways chosen to let me have what I want, are invariably quite different from those I had in mind. It’s as if Fate cared only about the end, not the means …

The narrator takes a summer job with the Forest Service, working with a man who goes around the woods of the Canadian North with his wife, looking for the budworms that destroy the trees.

I was eighteen, given to wild dreams, very apt to fall in love at first sight. …

My boss’s wife was pretty. … Sometimes she washed her hair in the lake, and then for a long time she combed it in the sun. … Sometimes at night I used to hear them laughing together. The laughing would fade into whispers, the whispers fade into silence. …

I thought I loved her. I thought I loved her far more than he did.

During a budworm expedition, the woman falls seriously ill. Her husband must take a boat across the lake to find a doctor, leaving the young man in charge. During the night, the boss’s wife is stricken with a terrible chill. She thinks she is going to die and invites the young man into her sleeping bag. Intending only to keep her warm, he removes his shoes and slips in beside her.

“Hug me tight,” she said. …

“Tighter.”

I hugged her as tight as I could. For a while she continued shivering; then she stopped. … I sensed that the heat of my body had done something to her. …

“Ah, I feel better now,” she said.

“I am glad, I am glad.”

“You are very warm.”

“Yes,” I said.

I was sure that Vivante himself had experienced something similar, creeping into that wide sleeping bag and later bravely and with inspiration turning reality into art.

After leaving Stanford, we settled in Southern California, where Joe took a job as a professor of history, and I stayed home caring for our baby, having a second and then a third daughter, all within five years. My little girls played at my feet as I wrote on my typewriter in our living room.

Around the time my first book of stories appeared, I discovered a new collection of Vivante’s: The French Girls of Killini. I bought it and noticed it was dedicated to Vivante’s editor at The New Yorker, Rachel MacKenzie, who had been my editor there, too.

I wrote him a letter in care of his publisher:

Dear Mr. Vivante—

It seems [from your stories] as though simple things cheer you, and though I hope you are not in need of cheering now that your book is being opened all over the country, I want to say it is a lovely book, and a lovely soul shines through to light every page.

I write in a spirit of both emotional and professional admiration … and, as a number of people felt obliged to apologize when they wrote me about my own collection of stories [Stop Here, My Friend ], “I am not given to writing fan letters.”

But I am not moved by too much modern fiction, either, and I had to make some outward response.

Best,

Merrill Joan Gerber

His reply came a month later from his family villa in Siena:

Dear Merrill Joan Gerber,

I received your letter today. It is a rare and beautiful letter. Thank you more than I can say. One responsive reader makes writing a book worthwhile. On such consonance of feelings my mind thrives.

I am so glad you told me about your work. I am eager to read your stories, and I am ordering your collection of them. Thank you again.

All my very best wishes,

Arturo Vivante

Two months later, I received another letter, not from Italy but from America, where he had moved in 1958. Selling stories, one after the other, to The New Yorker, he was earning more as a writer than as a doctor. In 1957, he had met a young American woman, Nancy Bradish, who had come into his practice with a minor ailment, and married her a year later. They were now living with their children in Wellfleet, Massachusetts.

Dear Merrill Joan Gerber,

I have now received and read “Stop Here, My Friend.” I was greatly impressed by the power of your writing. I don’t know how I missed the two [stories] that appeared in The New Yorker. I especially liked “The Cost Depends on What You Reckon It In.” What a fine story! The word story seems hardly enough for it, too little for it—it is life unfolding. It is so genuine and so forceful and you are so spirited—in each one of your stories. I was struck also by your picture on the book jacket. It has an Athena-like quality.

All my very, very best wishes to you,

Yours cordially,

Arturo Vivante

Immediately, I went to examine my picture on the book jacket. There was my regular face, which I was so used to seeing—in what way did it have an “Athena-like quality”? I began to see myself in a different light. I felt a rush of such gratitude! Heartfelt praise from Arturo Vivante. I had somehow stepped into the best moment of my life.

However, Fate had a hand in changing my situation: at age 55, my father became ill with leukemia, and within three months he was dead. I continued to relive his all-consuming suffering, moment by moment. My mother was stricken and nearly helpless in her grief, and I found myself unable to write. Any diversion felt somehow like a betrayal of his anguish. For a year I struggled, unable to play with my children, or even take any pictures of them.

Later, I would encounter Vivante’s story “The Bell,” which dealt with a son coming to terms with his father’s illness—“a slow and endless decline till the son begins wishing the end would arrive”:

“What is death like, I wonder,” he asked his father one such time. …

“It is a dim gray ward in which your senses fade little by little.”

And his son thought, This is the true picture. And, He’s perfectly right not to want to die. He has seen death, knows it from close by, has seen its gorge. … And the son thought of the orange eye of a cat gone opaque and dull. … From that time on, he didn’t increase the dosage [of the sleeping drops], not even by one drop, and though before he had wished—hoped—for his father’s death, he didn’t now.

My father had also seen death up close. Mustard gas was a desperate, experimental treatment then for leukemia. On the day he died, he said to my mother, my sister, and me: “There are going to be a lot of people in this room tomorrow night. There are going to be a lot of chairs in here. Listen! Do you hear the knocking at the secret door? If you’ll be quiet for a minute, you’ll hear it.”

None of us heard the knocking.

Eventually, I found the energy to begin writing a book about my father’s death. I wrote it in a frenzy of anguish and relief. By pouring into An Antique Man all I could remember about my father’s illness, I was secure in knowing I had honored his agonies and ours. Once the experience was safely between the covers of a book, I began to breathe freely again. I could hold my children and laugh with them. I could embrace my husband.

On June 23, 1967, Arturo scrawled this note to me in pencil from New York City:

Dear Merrill,

We are just about to sail for Italy, hence this hurried note. I did want to tell you, though, that I saw Rachel [MacKenzie at The New Yorker] yesterday. She is well, and spoke of you and of your book with admiration. She said it was very moving; that she wept throughout, and that she had also shown it to [William] Shawn. She means to write to you.

I did hear from Rachel MacKenzie—she told me that they had tried to find an excerpt from my manuscript that would stand alone in the magazine, but alas, they had not found a section that would work for them.

[adblock-right-01]

Within a couple of weeks, she wrote to me again. Her boss, William Shawn, could not get the book out of his mind, and would I please send the manuscript back to them. I did so at once, and lived in a state of almost unbearable tension, waiting for a reply. When the second rejection came, it was far worse than the first—they had concluded that a section of at least 100 pages was needed to stand alone, and that was too long for the magazine.

Vivante’s stories continued to be a guide for me as, in his fiction, he worked his way through painful, and sometimes joyful, life experiences. “The Binoculars” is about a man whose mother has died before he can fulfill a promise to her.

“How I’d like to go to the Abruzzi to buy dishes!” his mother often said. … “Just you and I in your little car—with room for only the dishes in the back. … Shall we go? Shall we go?” … But they hadn’t got around to going.

Then she had fallen ill. …

It was four months now since she had died.

Some years before her death, the son in the story had stopped in an Abruzzi mountain village where he found a little ceramics shop that sold dishes—“each cup, vase, plate, and saucer had a painting—a landscape with trees, a brook, a little house, and mountains in the background.” He had brought several dishes home to his mother. She had adored them, and begged to go with him so they could buy more. “Now it was too late to take her. Still, he felt he should make the trip—felt it almost as a duty.”

He travels to another remote village. He has with him a pair of binoculars that he uses on the trip to admire the mountains, the details of the little houses high in the hills, the colors of the wash hanging out to dry. When he stops at a ceramics shop, he buys nearly everything in sight, soup plates, cups, saucers, a vase … When he gets back to his car with his bounty of dishes, he discovers that his binoculars are gone. Some villagers tell him that an “odd” boy had no doubt taken them, a boy who had stolen before. The police are called, the binoculars are recovered, the boy is taken to the town hall. All seems to have gone wrong with this trip. The story concludes:

A few days later, at the table, waiting for food to be passed round, he stared into his empty plate. … What he saw was not the open sky, the little silver cloud … the flowers but a barred window.

“Aren’t these plates lovely!” a guest said to him. …

“Yes,” he said. “Yes. Lovely.”

He thought, The binoculars stolen, the boy in jail, and this woman here instead of my mother—they are all in keeping with each other.

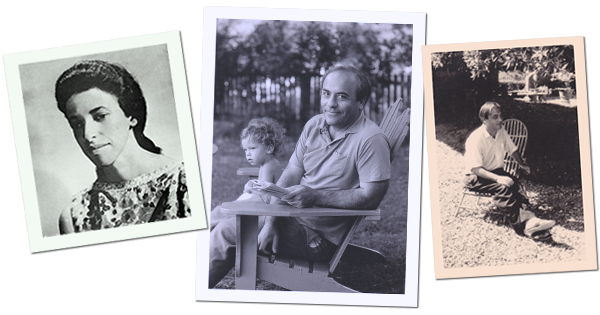

Vivante, pictured here with his son Benjamin in 1968, noted the “Athena-like quality” of Gerber’s dust-jacket photo. (left: Val Cheney; center: Bernard Gotfryd; right, at Solaia, Siena, c. 1950)

In 1970, my husband and I took a trip to Italy. I had written to Arturo that we were coming, and he had sent me his phone number, saying I must be certain to call him. I dialed Siena from our hotel room in Florence. A woman answered the phone, saying, “Pronto! ” She called Arturo’s name. There was a long pause, and then a tired, almost exhausted voice answered, saying, “Yes?” I told him who I was and asked if we might stop in to visit him at his home for a little while. “Yes, of course, yes, come, please, do.”

I asked what might be a good time, and he said, “We have lunch at 1:30, please come, it won’t be any trouble. Let me give you directions to the villa.” He instructed me in a distracted, wavery voice as I took it all down on hotel stationery.

“I’m looking forward to meeting you,” I said. “I can’t tell you how much!”

“Yes, I’m looking forward as well.” There was a pause, and then he said, “Who did you say it was? I didn’t quite get your name.”

“Oh my God,” I said to Joe after I’d hung up. “He doesn’t even know who I am!”

Villa Solaia was a pale yellow house at the top of a long hill. I was struck by the silence around us, not a bird calling, not a breeze stirring, just intense yellow heat, and silence. Joe and I crunched on pebbles as we approached the front door. Arturo was waiting inside the dim doorway, much heavier and older than his book jacket had pictured him. “Hello, welcome to the villa,” he said, and shook my hand and then Joe’s. Did he now know who I was? I thought I might say how peaceful it must be to live in the country, how conducive to work, how inspiring, but Arturo was shuffling his way down the dim hallway, murmuring, “Something to drink.” He returned with two glasses of wine. I took a sip, but it was bitter, and I set the glass down on a wooden table. There was the tinny sound of a cowbell, and Arturo said, “That will be lunch.”

We followed him through a dim, oddly cool hallway to a room where a huge dining table was set with many white plates. So this was the famous villa I had read about in his stories, the one where Americans and other tourists in Tuscany came to stay. Their patronage helped to support the upkeep of the big house and all its servants. Arturo’s wife came toward us introducing herself—a pretty woman with long brown hair laced with gray, and wearing a plain loose dress and beach slippers. “Please, you sit here, next to Arturo,” she said, and pulled out a chair for me at the table. She led my husband to the other side of the table, where she offered him a seat next to her. Around her were her three children, two little girls, and a curly-haired younger boy. Others came to the table, various travelers talking about pasta machines and luggage allowances and leather goods in Siena.

A man looking much like Arturo, who must have been his brother, was sitting farther down the table, smoking a pipe, appearing indifferent to the activity around us. I finally said to Arturo, “Your writing has meant a great deal to me,” but I saw at once he did not want to hear this, so I said quickly, “Do you often have guests here?”

“Very often,” he said. “Nearly always.”

“Does it interfere with your work, having so many people around all the time?”

“Sometimes they give me an idea.” Then he added, “They used to.”

[adblock-left-01]

An elderly servant woman came in wheeling a wagon holding an enormous steaming bowl of pasta and served each of the diners. Arturo passed a full bowl to me and began eating, so I ate silently beside him. After a time, I ventured another question: “Do you have a favorite among your stories?”

“I am tired of my own work. I am tired of thinking about what I did. I’m not doing anything now.”

“Do you know which story is my favorite?” I persisted. “The one in which the man goes to the Abruzzi to buy dishes for his mother, and then his binoculars are stolen.”

Suddenly, Arturo leaned back in his chair and stretched his arm behind him to open a cupboard against the wall. He pointed to the lower shelf, and there I saw the piles of hand-painted dishes that he must have bought for his mother.

I nearly gasped. “Oh!” I said. “I’ve always felt your stories ring with true life.”

“As do yours,” he said, and briefly put his hand over mine on the table. “As do yours.” And with relief I knew he knew who was sitting beside him.

After lunch, he walked my husband and me to the door. I said, “We are planning to reach Rome tonight, so we must leave now. But thank you so much for having us here to visit you. I will be looking for more of your stories.”

“At the moment,” he said, looking past me toward the hills, “there is nothing much to watch for.”

Inspiration must have returned, because I count 25 stories of Vivante’s from 1970 to 1981 that I clipped and saved from New Yorker magazines. During those years, when he was living mainly in Massachusetts and teaching at different colleges, we exchanged many letters and sent each other books we’d written.

In 1993, I asked if he might write a reference letter for me to the Guggenheim selection committee. “I am hardly the right person to ask,” he responded, “since of all the many writers I’ve recommended for it not one has received it—I’m just not influential enough, and little known. Also, in my old age, I’ve become very forgetful and weary.”

I replied:

Don’t worry about writing a Guggenheim reference letter. I have applied more than a dozen times and my turn-down letter always arrives on my birthday. … It is devastating at times to be a writer. Here is a letter of rejection I just got from an editor about my 800 page, three generation, family novel, The Victory Gardens of Brooklyn. … ‘Page by page this is far superior to most of the coming-to-America novels that I’ve published. The story has a leisurely observant quality that’s at odds with the requirements of the genre: Bottom line—it’s good but needs a great schlocky melodramatic plot!’ There are days I feel that being a writer is no more than begging and being bludgeoned.

His reply:

Your feelings are familiar. I can certainly identify with them. … To be a great success, such as Picasso was, you need to be a mirror of the times, which may not be all that desirable, the times being what they are. And then success isn’t the utmost of values; it could be viewed as an enviable state, and the wish to be successful as a wish to be envied. It also has to do with ambition, pride, power, and little to do with what really matters: inspiration, insight, wisdom. At best, it is satisfaction of recognition and testimony of one’s value, but not as sweet as honey, more like beet root. And the best seller lists are so appalling. Your writing is so live and tuneful!

Arturo and I continued to write frequently, and sometimes he sent me postcards filled with his tiny, wavering handwriting. When he was 82, and we had corresponded with each other for 40 years, I confessed to him that I had written a story about our visit to Villa Solaia and had sent it, in the 1970s, to Rachel MacKenzie. She told me they “couldn’t touch it,” since so many writers had visited Villa Solaia and had written stories about it over the years. Arturo begged to see my story. I found a yellowed, tattered carbon copy, which I sent to him. On August 8, 2005, he wrote:

Thank you so much for sending your story, “The Villa.” It is so very accurate in every detail, and you capture the atmosphere of the house admirably. I often regret having agreed to its sale. Your story, however, led me to think that the villa flourished in the 1950’s and 1960’s, and that, even if we had kept it, it would have been hard put to flourish again, like people, perhaps. Some of the lines brought a smile, or rather a laugh, to my face, eg, “both brothers wore a certain detached, patient air about them—not sad, not depressed so much as resigned and willing to endure.” The lines show your skill in characterization that I have admired again and again, I recognize most people, and especially myself in the story!

After Arturo’s wife, Nancy, died in 2002, his sense of gloom increased. That he had sold more than 70 stories to The New Yorker over his lifetime, an incredible achievement, seemed not to sustain him. He felt himself to be “little known and uninfluential.”

“I am not terribly well,” he wrote, “have a hard time walking any distance and drive almost everywhere, and often I find it hard to write even a letter.”

Yet in 2004, the University of Notre Dame Press published a book of his short stories, Solitude. He sent me a copy, and being so familiar with many of the stories, I thought I should review it. My review appeared in the Los Angeles Times on July 24, 2005. “Unlike Chekhov,” I wrote,

who called medicine his lawful wife and literature his mistress, Arturo Vivante gave up medicine entirely when, as a young doctor in Rome, he began to sell his stories to The New Yorker and decided writing was his true calling. Both professions require attention to the dimensions of suffering and pain, although Vivante seems to have been drawn more to the pain of the psyche than to the pain of the body.

I noted that Vivante “muses on the essential loneliness of our human existence and our yearning for connection.” And I wrote about how love “is a primary force in these stories, although not necessarily the love of a man and his wife.”

Arturo responded to my review:

What a delight to receive your letter with your splendid review of Solitude. … [Y]our review is the best I’ve ever had and it came at a time when I couldn’t have needed more encouraging to start writing again. … I think readers will be drawn to buy the book since the review is very inviting and the quotations very apt.

His energy seemed to rise. Within weeks, he told me that he had revised a novel he had written 10 years before. Then, some weeks later:

Merrill, here is my novel Truelove Knot. Thank you for being willing to read it. If it is a burden or you don’t have time, send it back, I enclose an envelope. When I wrote the novel I thought it was my best work but now I just don’t know. They often say that writers aren’t the best judges of their work. I certainly value your opinion and would be extremely interested to hear what you think of it.

I made some suggestions for changes, which he incorporated into the text. Shortly thereafter he wrote:

Notre Dame Press sent me the contract and I signed it on the theory that an egg today is better than a chicken tomorrow. ‘Meglio un uovo oggi che una gallina domani.’

Despite his rise in spirits, he found himself growing weaker:

It would be lovely to meet you and your husband when you visit your daughter in Washington this winter, but oh dear I am getting so old and a long trip worries me. I have terrible dreams of getting lost in strange cities. I should go to Italy one last time to look after my little apartment in Bomarzo which I bought after my family sold Villa Solaia in Siena. My children seem to have little time or inclination to go there for any length of time but they don’t want to sell it. I bought a computer, hearing aids, and I use a cane for any distance outdoors.

After getting the computer, Arturo seemed triumphant in his ability to use email, and his letters came to me with a new look and a new speed. Then another piece of good news came his way. The Academy of Arts and Letters in New York was to give him the Katherine Anne Porter Prize, with an award of $20,000. “You are the only writer I am corresponding with now,” he wrote. “Inspiration, I expect, will visit you unannounced and you will soon be writing a new story.”

And then:

At the awards ceremony in New York I was approached by an agent, but the University of Notre Dame Press had already accepted the novel. … [T]he ceremony went well though the trip was rather tiring as was my recent journey to Italy. It was pleasant to walk around the old streets of Rome and to be at my village in Bomarzo where I spent most of my time. The atmosphere was very festive with a concert right in my little piazza which I viewed from my balcony. At one point a young man stood up and played a clarinet solo very melodiously.

In August 2006, there was another surprise:

I sent Solitude to a girl I wrote about long ago in The New Yorker, May 1982, who is my daughter. Her mother came to Villa Solaia in 1967 with her husband. … He was away for two weeks. I went for a walk in the woods with his wife and a year later she called me to come and see her in Florence. I went and she told me that I was the father of a little girl. I saw her and held her in my arms. … When the girl was ten, her mother died of a heart attack and her father died, too. … For years I didn’t have the heart to reach her. But I finally sent her my book with a note saying I was a friend of her mother. She immediately phoned me. She is a brunette and suspected that her father wasn’t her father. A week ago she flew here and we had a very happy reunion.

Arturo told me he felt ill and weak, that everything he was doing now was a move to “concluding”—his last visit to Bomarzo, meeting his daughter again, and then her meeting his children at his home in Wellfleet—“a jolly time we had, eleven around the table.” And his letters came less often.

I wrote to him about having an abnormal EKG and being rushed to a hospital to have an angiogram. “No one could find either vein or artery,” I wrote, “and other doctors had to be called in—by the end of it my leg was deeply mashed up. Though they didn’t find blocked arteries they did find a thickened heart muscle, so we are in deep waters here, you and I.”

His reply, the last letter he sent me, on December 23, 2007, moved me almost to tears:

Dear Merrill, your description of the tests and exams that you endured strikes a sensitive and familiar note. Your dear heart! Your limbs that should not know needles and electrodes but rather kisses and caresses.

Yet I also had to smile, knowing that Arturo had charmed women all his life. I recalled the wife’s words in the story “Company”: “you and all your girlfriends …”

In that same letter, he also told me he had been diagnosed with cancer:

There are no particular treatments for me except symptomatic ones. I am not particularly calm but the pain is very slight and temporary and is taken care of by the analgesics.

Thank you for your second email about [my mention in] The New Yorker. Vanity is present even when one is ill and I appreciate your telling me about it. I had not seen it, though. [My daughter] Lydia will get one for me tomorrow.

Love, Arturo

Arturo died on April 1, 2008. His daughters and son dispersed his ashes to the ocean that he loved, on the night of a full moon in Wellfleet.

Two days after I finished writing this essay, I stopped at a little thrift shop in my town. A man had come in to donate a pile of dishes, which he left on the counter. The dishes were delicately painted with sprays of tulips, roses, and poppies all rising from a starburst of lacy green leaves. I turned one over. It was signed with the artist’s name and the town in Italy in which it was painted. In a state of astonishment, I bought all the dishes for one dollar each and took them home, where I put them with a sense of reverence in my dining room cabinet.