A Life’s Work Gone to Seed

The lost cultivations of an often overlooked colonial scientist

American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic by Victoria Johnson; Liveright, 480 pp., $29.95

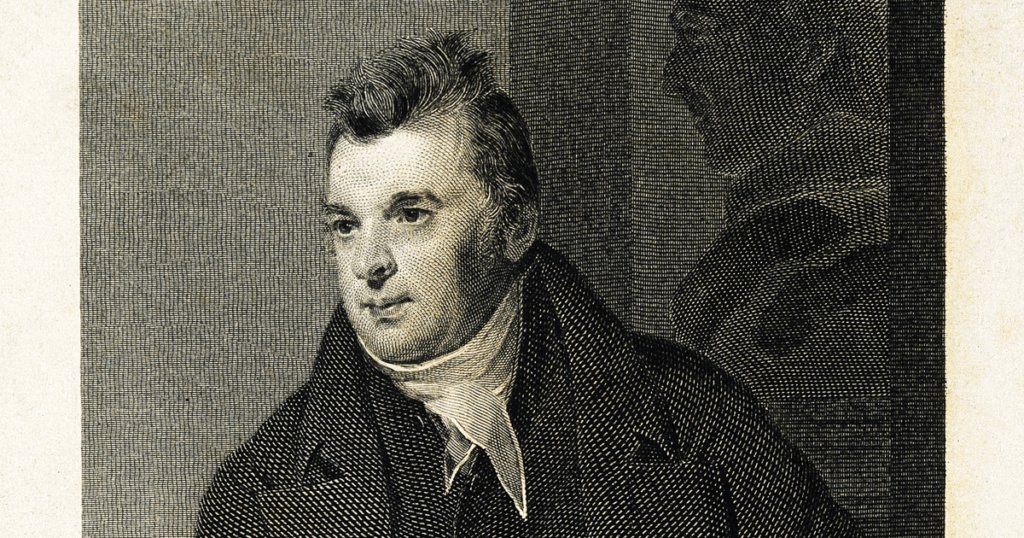

Sometime around 1820, the U.S. Mint struck a medal designed by Moritz Fürst in honor of Dr. David Hosack, who is the subject of Victoria Johnson’s American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic. On the obverse of the medal, Hosack is shown in profile. He’s a solid man, with a substantial curve of flesh joining his plump chin to his neck. He has pendulous earlobes and a curious coiffure that licks flamelike toward the top of the coin, perhaps as a sign of his energy, his industriousness, his irrepressible desire to set others afire with his plans and projects. Looking at that face, you can see why one contemporary wrote that Hosack was “manly and dignified … affable and engaging.” You can also see why the botanist John Torrey found him “overbearing.”

Perhaps it takes an overbearing man to accomplish as much as Hosack did in his lifetime (1769–1835). He was as good a doctor, scientifically speaking, as it was possible to be in that era. He was—again, according to a contemporary—“one of the greatest botanists of the age.” He was also an arch-instigator, a founder of organizations and associations, like the New-York Historical Society. He worked for years to create a 20-acre private botanical garden—Elgin Garden—but was unable, in the end, to turn it into a lasting, public institution. And yet David Hosack will always, and perhaps mainly, be remembered as the doctor who was present when Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton, the doctor who was with Hamilton when he died.

American Eden is Victoria Johnson’s effort “to bring David Hosack into living relief.” It’s a difficult task. Hosack was no Humboldt. He was a man of the classroom, the laboratory, the committee, the library, the club, the garden. He wasn’t an adventurous traveler or a botanical explorer—he was the man to whom explorers sent seeds and plants. Hosack’s life was extremely full—he married three times, had many children, taught many fine doctors and botanists, knew absolutely everyone, wrote a great deal—and yet the story of his life, apart from a few exceptional incidents, isn’t especially compelling, as stories go.

Johnson’s research is impeccable, and American Eden is clearly a labor of love. But I wish the book had been what I think it really wanted to be: an intellectual history with an ensemble cast, organized thematically, largely free of chronology, instead of a time-driven narrative of one man’s life and his connection with the lives of others. The prevailing wisdom seems to be that readers don’t want to hear about ideas; they’d rather hear a good story about people who occasionally have ideas. Writers are often told, for instance, that the best way to write about science is to write instead about the lives of scientists. The result is a structural cliché based on a false assumption. That’s what causes the tension you can detect in American Eden—the effort to personalize the period and the place, to vivify the narrative through the thoughts and especially the feelings of Hosack, as if the reader wouldn’t otherwise care. Johnson does this partly by vivifying her own writing in ways that are sometimes melodramatic and sometimes just silly.

Here’s what I mean. One of the gardeners at Elgin Garden was John Eddy, Hosack’s nephew, who happened to be deaf. It’s an emotive opportunity not to be missed. “He could not hear,” Johnson tells us, “the waves beating against the Paulus Hook ferryboat, the whisk of dry grass around his ankles as he crossed a field, or the snap of a branch between his hands.” In fact—of course!—the list of sounds that John Eddy couldn’t hear is limitless. Of another of Hosack’s contemporaries, Johnson writes, he “had the look about him of a man who could not reach for a quill pen without a fluttering of soft white cuffs.” This is a sentence from a romance novel. Aaron Burr’s daughter vanishes at sea, and here too the heartstrings must be plucked. “Now [Burr] would never pull a chair close to hers and laugh with her about the fascinating, maddening people he had met in Europe. He would never dazzle her with stories of the palaces, the landscapes, and the gardens he had seen. He would never get to take her little hand in his again, or that of his only grandchild.” How is the reader served by this? When Johnson says that “the farmland” Hosack turned into Elgin Garden “now lies dormant beneath the limestone and steel of Rockefeller Center,” I want to assure her that the soil that made it farmland in the first place was blasted and trucked away during construction in the early 1930s, if not long before.

When Johnson writes well—plainly and without trying to entice the reader—she writes very well. But American Eden practically swims with chronology, and the result is verb tenses darting about like unschooled fishes. She’s so busy trying to propel—and follow—the narrative that she’s unable to give her central themes the sustained attention they deserve. One such theme is the fate of science in a hard-headed commercial nation at a time when science was still being defined. Another theme is the fate of philanthropic institutions. Why do they succeed and how do they fail, especially in an immature society? And what about the relationship between medicinal botany and medical practice in the early 19th century? These are excellent subjects.

Hosack was both a joiner and a founder, a man who reveled in turning good ideas into well-governed associations of well-intentioned men. He believed strongly in the value of publicly funded science. He spent a fortune creating a botanical garden dedicated to the practical uses of plants—a garden that was purchased, after much delay and political maneuvering, by the State of New York and then essentially abandoned. Perhaps Hosack’s Elgin Garden was the wrong model for such an institution. Or perhaps it was simply the wrong time. After all, the New York Botanical Garden wasn’t founded until 1891, 56 years after Hosack’s death. His garden may have faded away—its plants scattered, its buildings demolished—but it advanced the idea, in a raw, young country, that public institutions committed to scientific understanding are a fundamental mark of civilization.