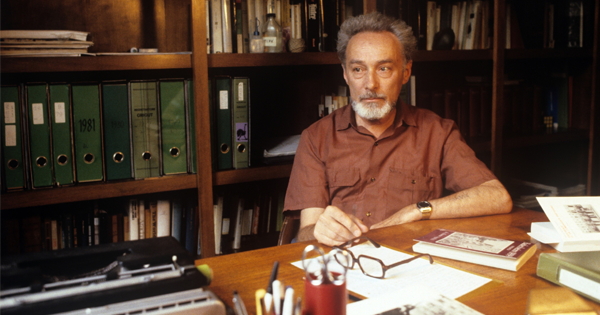

A Lifetime Spent Bearing Witness

The literary giant who rose from the ashes of a people

The Complete Works of Primo Levi by Primo Levi; edited by Ann Goldstein; Liveright, 3,008 pp., $100

The issuance in English translation of The Complete Works of Primo Levi, arranged in the order that Levi wrote them, is a major and most welcome cultural event. It will astonish most of Levi’s English-speaking readers by revealing the richness and extent of his oeuvre. The translations from the Italian are new, with one exception: Stuart Woolf revised his beautiful rendition of Levi’s first book and masterpiece, If This Is a Man, an account of Levi’s time as a prisoner at Auschwitz, to reflect changes the author made subsequent to the book’s initial publication in 1947. Its companion volume, The Truce (Italian, 1963; English, 1965) is a picaresque and often harrowing account of Levi’s seven-month voyage back home to Turin following the liberation of Auschwitz. The journey took Levi, after an extended stay in a transit camp run by the Soviet army, through Poland, Ukraine, Slovakia, Austria, and southern Germany. Also here are The Periodic Table (Italian, 1975; English, 1984), his widely praised autobiographical essays, heartbreaking and tongue in cheek, each of which is thematically connected to an element known to inorganic chemistry, and The Drowned and the Saved (Italian, 1986; English, 1988), a majestic summing up of Levi’s concentration camp experience and meditation on its meaning. These works are accompanied by a dizzying variety of other writings: essays and short stories; a full-length novel called If Not Now, When? (Italian, 1982; English, 1985), about a band of Jewish partisans, a popular success but, in my opinion, of scant literary merit; and most surprising, a collection of Levi’s poems, fluidly translated by Jonathan Galassi.

Levi was born in 1919 in Turin, the principal city of Piedmont, into a well-off family of Jews originally from Spain and Portugal who settled in the region in the 16th century. The family was assimilated, like others of its kind, and Levi himself was an agnostic. But Auschwitz taught him what being a Jew meant and turned him into an outright atheist. The racial laws excluding Jews from public schools and universities, military service, government careers, and other forms of employment came into effect in Italy in 1938. Because Levi was already studying chemistry at the University of Turin, he was allowed to continue there and, in 1941, obtained his doctorate with honors. Finding work as a chemist was difficult for a Jew, but Levi did so twice, first near Turin, then in Milan. In late 1942, he joined the anti-Fascist underground and was with a small group of partisans in the Valle d’Aosta, in the Italian Alps, when on December 13, 1943, they were betrayed and arrested by the Italian military. Many of these events are described in The Periodic Table.

[adblock-right-01]

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, when arrested Levi identified himself as a Jew and was sent to a concentration camp operated by the Italian military near Modena, in Fossoli, subsequently taken over by the Germans. From there, Levi and hundreds of other Jewish prisoners were loaded on cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz, where a selection took place upon arrival. Only 95 men and 29 women entered the camp. All the others—men, women, and children—were gassed and cremated. If This Is a Man tells the story of Levi’s time at Buna-Monowitz, an Auschwitz subcamp, owned and operated by German industrial giant I.G. Farben, where inmates were compelled to work in the production of synthetic rubber, among other materials. Levi survived the brutal treatment, hunger, and extreme cold of the Polish winters due to a combination of factors: his imprisonment after the Germans, faced with manpower needs, decided “to lengthen the average lifespan of the prisoners destined for elimination … and temporarily suspended killings at the whim of individuals”; his knowledge of German, which enabled him to understand orders and escape most beatings; a strong constitution; the near-miraculous help of an Italian civilian worker, who for six months gave him bread and the remains of his own soup rations; his having been chosen in November 1944 to work as a chemist in the Buna laboratory; and paradoxically, a severe case of scarlet fever he contracted in January 1945. He was in the camp infirmary when the order came to evacuate, after which Auschwitz prisoners embarked on what for most of them turned out to be a death march toward the West, away from the advancing Soviet troops. Too sick to walk, Levi remained in the infirmary. He and the other sick prisoners expected to be executed by the Germans before they departed, but, presumably forgotten by the last fleeing SS contingent, most of them were still alive when Soviet soldiers liberated the camp.

Once Levi published If This Is a Man (begun on scraps of paper in the ice-cold laboratory in Buna), he launched a prolific career as a writer. All the while, he remained a working chemist, until he retired in 1975 and devoted himself to writing full-time. Success came slowly. The small publishing house that issued If This Is a Man printed only 2,500 copies, of which, notwithstanding favorable reviews, just 1,500 sold, principally in Turin. In 1958, the book was reissued in Italian by Einaudi, a large house that like many others had rejected it 10 years earlier but which thereafter became Levi’s regular publisher. This time the book took off, and not only in Italy—Stuart Woolf’s English translation appeared the following year, and in 1961, of special importance to Levi, came a German translation.

In 1947, Levi married Lucia Morpurgo, of a Turin Jewish family much like his. They had two children and continued to live in the apartment where Levi was born. His last years, if one can put aside literary output and adulation, were grim. He underwent an operation for cancer of the prostate. His nonagenarian mother, who lived with him in the same apartment, was paralyzed after a stroke. Caring for her became a heavy burden on Levi and his wife, and Levi began taking medications to relieve his depression. On April 11, 1987, he died of a fall down the stairwell outside his fourth-floor apartment. There was no suicide note, and the question of whether he fell intentionally or by accident has long been the subject of debate among his friends and biographers. Lucia remained a widow for more than 20 years.

“We have reached the bottom. It’s not possible to sink lower than this.” Levi came to this realization upon his arrival in Auschwitz, after the prisoners had their clothes taken away and were shorn and tattooed. They had even lost their names: they became the numbers inscribed on their forearms. The induction process led to his other fundamental insight: the Germans’ design to dehumanize the prisoners. The purpose was not only to break their will and capacity to resist but also to facilitate a regime that killed other human beings, either slowly, by starvation, exposure, and hard labor, or quickly, by sending to the gas chamber prisoners judged unable to work (the old and the sick, most women, and all children). Or, as Levi put it elsewhere, “before dying, the victim had to be degraded to alleviate the killer’s sense of guilt.” The corollary was the victims’ nightmare: miraculously they return home and relate to a loved one what happened to them. But they are not believed or even listened to, such was the enormity and thus the unbelievability of what had occurred in the camps, in the ghettos, behind the lines of the Eastern Front. Hence the survivors’ absolute obligation to bear witness, to describe the indescribable, and to make themselves believed. Levi discharged this duty triumphantly in works of unequaled intellectual rigor, compassion, and modesty.