A New Heaven and a New Earth

During the Spanish Civil War, an alternative vision of society briefly flourished in Barcelona

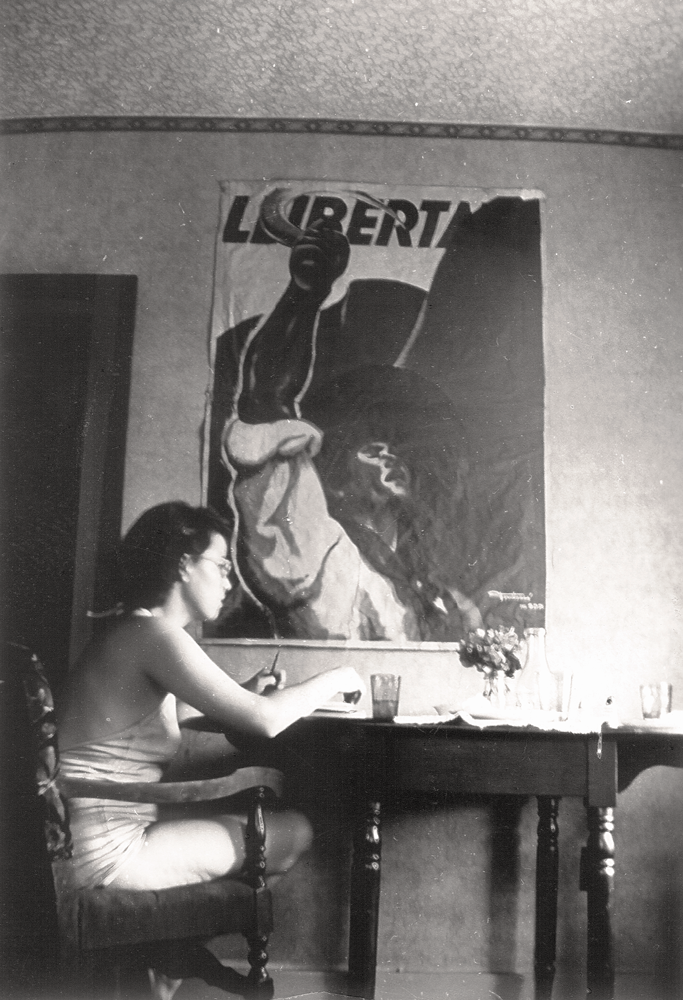

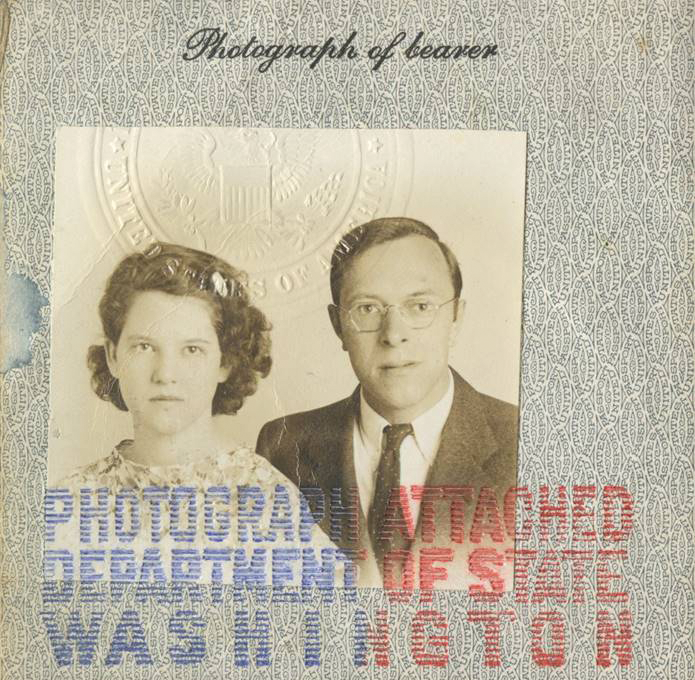

In the summer of 1936, a young American couple headed to Europe for a most unusual honeymoon. Like so many others in those years, Lois and Charles Orr were convinced that the Great Depression had proved capitalism a failure. Five feet six inches tall, Lois had light brown hair and spoke with a Kentucky drawl. A sophomore at her hometown University of Louisville, she had married Charles, a decade older and an economics instructor, earlier in the year. The newlyweds set off to witness the various forces that seemed destined to shape their world. Early in their wedding journey came a visit to Nazi Germany, and they planned to travel onward to India for a firsthand look at British colonialism. But then came riveting news from Spain.

A large group of army officers, calling themselves Nationalists, had staged a military coup against the elected government of the Spanish Republic, igniting the Spanish Civil War. In a matter of weeks, backed by arms, aviators, and supplies from Hitler and Mussolini, they had taken over more than a third of the country. But what most fascinated independent-minded progressives like the Orrs was the parts of Spain where the coup failed. In those regions, the military conspirators were turned back by ill-trained, barely organized militias.

These ragged volunteer forces were formed by trade unions or left-wing political parties and often managed to equip themselves only by breaking into armories, gun shops, or, in one case, a prison ship where they seized the warders’ rifles. Thus armed, people began seizing power for themselves. Workers took over factories. Waiters took over restaurants. Barcelona’s trolley drivers took over the transport system. The most tantalizing reports came from that city. The great Liceu opera house—one of Europe’s largest—was turned into a people’s theater; political murals several stories high covered the outsides of buildings; pawnshops were forced to give objects back to their poorer customers. Mansions confiscated from the wealthy now housed the homeless; and the restaurant of the Hotel Ritz, with its elaborate chandeliers, white linen, and monogrammed china, had been turned into a people’s cafeteria for the poor.

The Orrs and other radicals were thrilled. Wasn’t this what they had long dreamed of? Except for the short-lived Paris Commune, little like it had ever happened in Western Europe. And these events were particularly attractive to democratic leftists dismayed by the emerging police state in the Soviet Union, for here was a revolution not imposed by a single-party dictatorship, but being made from the bottom up.

At the center of the upheaval were anarchists, adherents of a creed that thrived in Spain as nowhere else in the world, particularly in Barcelona and surrounding Catalonia, in the country’s northeast. Spanish anarchists believed in comunismo libertario, libertarian or stateless communism. The police, courts, money, taxes, political parties, the Catholic Church, and private property would all be done away with. Communities and workplaces would be run directly by the people in them.

For Charles and Lois, hearing fragments of news was not enough. They suspended the rest of their honeymoon plans and began hitchhiking through France toward Barcelona, the epicenter of what people like them were calling the Spanish Revolution. It was Lois, the more adventurous of the two, who insisted they make the journey. She was 19 years old.

On September 15, 1936, a rainy morning two months after the start of the Nationalist uprising, the couple walked across the border and into the most revolutionary corner of Spain. “We found ourselves,” wrote Lois, “surrounded by a crowd of dark, unshaven militiamen in wrinkled blue coveralls, with red and black neck scarves. … Each anarchist had a heavy black rifle on his shoulder and a pistol at his belt. … ‘Why have you come to Spain?. … How do we know you aren’t Nazi spies?’ ”

The militiamen were alarmed by the German stamps in the Orrs’ joint passport. A letter attesting to Charles’s membership in the Socialist Party of Kentucky was no help. They were hustled into a car and driven away for questioning. “Most of the young comrades of the Frontier Control Committee came along with us for the ride,” Lois remembered. “Jammed together, rifles sticking out the windows, we tore off at top speed. The narrow road wound back and forth around hairpin turns, like the all-too-familiar roads in Harlan County, Kentucky. In the valleys far below us were wrecked cars. … Not an encouraging sight.” Finally, a local anarchist English teacher examined Lois’s diary and assured her comrades that the pair were not Nazi agents.

The Orrs were thrilled when they boarded a bus for the next stage of the journey. “I held out my pesetas,” Charles wrote, “to pay the fare. … The driver ostentatiously refused my filthy money. This bus, he proudly announced, was operated ‘in the service of the people.’ ” Continuing by train, they were delighted to find that first and second class had been abolished; only the hard benches of third class remained.

When at last they reached Barcelona, a big banner at the railway station read, welcome foreign comrades. Anarchist flags—red and black divided by a diagonal line—hung from balconies and from ropes strung across streets. The sides of street-cleaning trucks sported quotations from the 19th-century anarchist writer Mikhail Bakunin. A sidewalk barrel organ played “The Internationale.”

The couple was awed by a city that seemed to be transforming itself. More than a quarter of Spain’s population was illiterate, but political posters in bold designs could be understood by all, evening adult literacy classes were free, and the number of children in Barcelona’s schools would more than triple during the first year of revolution. On the Ramblas, a boulevard lined with plane trees—“the only street in the world which I wish would never end,” said the playwright Federico García Lorca—hats had largely disappeared. “Pirates, buccaneers, princes, señoritos [young gentlemen], priests—these are the hatted folks of history,” an anarchist newspaper proudly proclaimed. “What has the free worker to do with this outworn symbol of bourgeois arrogance? … No hats, comrades, on the Ramblas and the future will be yours.”

Anarchists hated the Catholic Church passionately, bidding farewell to each other with salud rather than adiós, which is short for “I entrust you to God.” Nonetheless, they mirrored Christianity in their vision of a judgment day when priests, capitalists, and bureaucrats would be struck down, and of a heavenly future, when cooperation and love would reign in place of greed and exploitation. They referred to this coming moment as the “anarchist millennium.”

“Barcelona’s Ramblas was dazzling,” Lois remembered. “Red, yellow, green and pink handbills and manifestos floated about our feet. Bright lights on … cafés, restaurants, hotels and theaters lit up red or red and black banners saying Confiscated, Collectivized … or Union of Public Performances.” By late 1936, throughout the Republican-controlled portion of Spain, more than a million urban laborers and some 750,000 peasants were employed in enterprises or farms newly managed by their workers. In towns and cities, these involved some 2,000 entities, including everything from power plants to flower shops. Nowhere had the old order been overturned more thoroughly than in Catalonia, where workers had taken over more than 70 percent of all factories and businesses. Workers’ collectives “opened clinics and hospitals in lush private villas,” remembered Charles. “Every automobile in the street was decorated with the initials and colors of one or another workers’ organization. There were no more private cars.”

Everything delighted the American newcomers, from the bullfight held to raise funds for the militias—the matadors entered the ring offering the left-wing clenched-fist salute—to a collectivized restaurant they dined in. One of the two brothers who owned it had fled, a waiter told them; the other, whom the waiter pointed out, had remained behind and, because he knew bookkeeping, had been elected cashier. Lois, for all her fiery radicalism, had a keen eye for unexpected detail: “The Anarchist trade unions have adopted Popeye as their own pet mascot. … Everywhere they sell pins, scarves and statues of Popeye waving an anarchist flag of black and red.”

In some ways, Spain was more confusing than they anticipated. Having returned from visiting the headquarters of the United Socialist Party of Catalonia, where he had expected to be welcomed, Charles wrote, “I was received by a lady who spoke English. … I tried to impress upon her that I was not only a socialist, but a revolutionary who had come to offer my services. … ‘There is no revolution’ she answered sharply. ‘This is a people’s war against fascism.’ … I then realized I had been sent to communists.”

Charles had stumbled upon a major political fault line. Catalonia and other pockets of the country were indeed in the midst of a social revolution without parallel. But it was one opposed by much of the Spanish Republic’s political spectrum, from the Moscow-oriented Communists to the middle-class liberal parties. The mainstream parties were no enthusiasts of revolution to begin with, whereas the Communists were leery of one spontaneously erupting from below and not orchestrated by the Party, Soviet-style. Both groups were desperate to buy arms from Britain, France, and the United States. They were convinced—not unreasonably—that these nations would never sell weapons to a Spanish Republic that appeared too radical.

Most anarchists, however, believed that without a revolution they would lose the war, which was going badly. The fascist-tinged Nationalists, now under the leadership of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, had continued to gain ground since the fighting had erupted in July. “We carry a new world in our hearts,” declared the charismatic anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti, a former railwayman and machinist. Unless there was a new world to fight for, sympathizers like the Orrs believed, the people would not rally to defeat Franco.

“If only,” Lois wrote wistfully, “they would make their revolution in some other language.” What Spanish the couple understood—Charles had lived in Mexico for a few months—was of little help, for in Barcelona they were surrounded by speakers of Catalan, “a language,” as Lois described it, “of hissed sibilants and clipped final x’s and t’s.” The Orrs’ Spanish remained rudimentary, and their lack of Catalan meant that the people they talked to were mainly other foreigners. “Those all-night sessions at the Café Ramblas,” Lois wrote, “were my first initiation into the political realities of Europe’s concentration camp universe.”

By eight weeks after their arrival, they had both found work. Lois began writing press releases in English for the Catalan regional government; the 10 pesetas a day she received (worth about $25 today) was “the first money I ever earned in my life,” she exulted in a letter home. Charles produced English-language shortwave radio broadcasts and edited a newspaper, The Spanish Revolution, for the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, or POUM. This small group was as left-wing as its name and shared with the anarchists the belief that only thoroughgoing social revolution would inspire workers to defeat the Nationalists. Lois also sometimes went on the radio for the POUM’s daily English broadcast, but the transmitter was so weak that she never knew whether anyone abroad could hear.

The couple first lived in a confiscated hotel where, as workers for the revolution, their meals were free. “Every day,” Lois wrote, “a truck brought huge rounds of bread to the manager’s office, to be stacked next to 100 kilo bags of potatoes.” Miraculously, it seemed, in a cashless barter system, peasants supplied the city with truckloads of vegetables, rabbits, and chickens in return for goods from Barcelona’s factories. Breakfasts, Charles reported, “came from an inexhaustible supply of large sardine tins. Our noon-day meals were enhanced by floods of really excellent bottled wine. These supplies, it was said, had been ‘liberated’ from the cellars of the rich.”

Along with other foreign supporters, the Orrs were, some five months after arriving in Barcelona, given quarters in a luxurious apartment in the hills above the city, confiscated from the consul of Nazi Germany. The consul’s papers, Charles reported, were being put to good use in the bathroom. “You should see our 10 room magnificent appt! … We have hot water, electricity & all. No one collects! I don’t know how long it can last.”

Parades and rallies took place almost daily. At the headquarters of the anarchist trade union federation—a building seized from the chamber of commerce—Lois found unionists using stock certificates for scratch paper. “We were living the revolution instead of our own personal lives, an incredible expansion of consciousness. … Everything was new and different, anything was possible, a new heaven and a new earth were being formed.”

Lois imagined the new heaven and earth in all she saw. “I completely lost myself in the life of the revolution, leaning on the railing of the tall balcony-window … and watching the black-clad women below drawing water from the plaza fountain for their cooking. … It was the regular tertulia of the neighborhood. The tertulia is a conversation group which meets for years in the same café, village square, or here, barrio plaza to sift out the meaning of the events of the day, of the decade, the generation or even life itself.”

Perhaps. On the other hand, these neighbors could well have been talking—in the language Lois knew barely a word of—not of the meaning of life itself, but of the price of bread. Or, for that matter, of their resentment over the endless political rhetoric on all sides, for not everyone in Barcelona shared her excitement. Thousands of workers tried to shirk service in the militias. A surge in union membership may have been due less to the dawning of a new millennium than to the fact, as one scholar points out, that “life in revolutionary Barcelona was quite difficult without a union card.” You often needed one to obtain housing, welfare payments, medical care, or food.

“I’m having the time of my life here,” Lois wrote to her family. “For any good revolutionary … Spain is the most valuable place in the world to be.” Such confidence was easy to have in Barcelona in the autumn of 1936. Just walking to work each morning, she could see churches that had been converted into cooperative workshops, cultural centers, refugee shelters, or public dining halls. Changes in the countryside were even greater. Rural Spain was a land of big estates, but in territory held by the Republic, previously landless peasants had taken over more than 40 percent of the arable acreage, more than half of which they now cultivated communally. In hundreds of these collectives, people made bonfires of property deeds—and of paper money.

[adblock-right-01]

Replacing money, some collectives issued coupons that symbolized the value of a given number of hours worked, with families that had more children receiving more coupons. (The system often came to grief when the coupons were not honored in the next village.) Some collectives grew more food than the estates they replaced. In Aragon, the equal to Catalonia in revolutionary fervor and with a higher percentage of collectivized farmland, food production increased by 20 percent.

Even names given to newborns reflected anarchist beliefs: one activist christened his daughter Libertaria. The movement’s hatred of bureaucracy extended to marriage. In a coastal village south of Barcelona, a French anarchist writer, Gaston Leval, came upon this scene:

Four couples have been united since the beginning of the revolution. Accompanied by their families and their friends, they appeared before the secretary of the committee. Their first and last names, their ages and their desire to unite were recorded in a register. Custom was respected and the festivity was assured. At the same time, in order to respect libertarian principles, the secretary pulled out the page on which all these details were inscribed, tore it into tiny pieces while the couples were descending the stairway, and, when they were passing under the balcony, threw the pieces at them like confetti. Everyone was happy.

However much Lois romanticized what they saw, she and Charles were indeed living in a city that had turned the normal social order on its head. No one knew how long this extraordinary political moment would last, but while it endured, it drew sympathizers from all over Europe. One of those political pilgrims, who ate in the same communal dining room as the Orrs and worked in the same building as Charles, was a 23-year-old political exile named Willy Brandt, who went on to become chancellor of West Germany. Someone who would later win even more renown was about to arrive.

Although Charles Orr had seen more of the world than his wife, neither of them seems to have been much aware of a crucial part of the history they were living through.

The anarchist tradition was curiously contradictory. The movement’s prophets held out an inspiring, gentle vision of the millennium, and some of its thinkers embodied this spirit in their own lives. The Russian theorist Pyotr Kropotkin, for instance, was beloved by nearly everyone he met, from workers and peasants to curious business leaders and philanthropists. (It helped that he was a superb raconteur in five languages, played the piano, and had been born a prince.) At the same time, he and almost every other anarchist leader of note was in love with the idea of “the propaganda of the deed”—the great, shocking action that would cause people to rise in revolt and bring closer that day when parasitic bureaucracies such as armies, corporations, political parties, and governments would all vanish. What was the deed? Much of the time it was assassination.

Between 1894 and 1914, anarchists assassinated no less than six heads of governments, including President William McKinley of the United States and two prime ministers of Spain. In the 1920s, Spanish anarchists, reacting to the killings of union leaders by police, assassinated yet another prime minister, an archbishop, and many other officials, and tried unsuccessfully to kill the king.

Now, with Spain locked in a bitter civil war, this idealization of killing had reached an apocalyptic scale. “We must burn much, MUCH, in order to purify everything,” declared an anarchist newspaper. Not only the anarchists and POUM members, to whom the Orrs felt politically close, but also the Communists, whom they hated, had been responsible for much bloodshed throughout Republican Spain. The worst of these killings happened before the Orrs arrived, but Charles noticed a few clues to continued violence: “There were two Italian comrades, tall and handsome, attached to the POUM. They came around our offices from time to time, but had no obvious jobs. They carried pistols in their belts. My colleagues told me that they were the POUM’s trigger men … hinting that they knew more than they cared to tell.”

Scholars today estimate that more than 49,000 civilians were killed in Republican territory during the war, including nearly 7,000 members of the clergy. There were many more political murders in Nationalist-controlled Spain: some 150,000 during the war, and at least 20,000 more executions afterward. By the end of 1936, the Republican government, for its part, had brought such deaths almost entirely to a halt, but the killings had helped doom its hope of buying arms from the Western democracies. The only major nation willing to provide desperately needed weapons, pilots, tank drivers, and military advisers was the Soviet Union. But in return it demanded high positions for Soviet and Spanish Communists in the Republic’s army and security forces—as the Orrs would soon see.

One morning in December 1936, a lanky Englishman with a pronounced stammer appeared in Charles Orr’s office, eager to volunteer for the fight against Franco. His name, he said, was Eric Blair. This meant nothing to Charles and Lois—they had not heard of the several little-noticed books the rangy newcomer had published under a pen name, George Orwell. But he was eager to fight. A week later, he left for the front with a POUM militia unit and some six weeks after that, his wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy Blair, arrived from England and began working as Charles’s secretary. She became one of the couple’s best friends in Barcelona.

By early 1937, the city began to change. As she walked to work each day, Lois Orr noticed that some men were again starting to wear neckties, while many collectivized shops and businesses were being quietly returned to their prewar owners. “It is terrible to realize that the things that the workers took over for themselves, after years of oppression and misery,” she wrote to her sister, “are slowly being given back.”

She blamed the changes on the hostility of the Republic’s government and its Soviet advisers toward Catalonia’s social revolution. In this she was not wrong, but it was far from the only reason the anarchist dream was running onto shoals. It is hard to picture how a deep abhorrence for any kind of government and for the use of money could be combined with life in an industrialized society. You can imagine bartering eggs for bread, but what if the goods involved are aircraft parts and x-ray machines?

Other complications emerged, too. The Orrs were not the only people who hadn’t been paying their electric bill. Nor was the local electric utility the only enterprise—worker controlled or not—that had trouble collecting money owed to it. After the first flush of revolutionary enthusiasm, the old ideal of “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs,” however splendid in theory, proved difficult to enforce, especially when many workers decided their needs were for more time off.

The anarchist dream faced a still deeper problem. Changing who owns a factory is one thing, but changing attitudes that have come down through the centuries is quite another. “A people as a whole … cannot abandon their inherited ways,” Charles observed, even though “thousands turned out to celebrate any occasion and to shout themselves hoarse to the most revolutionary slogans.” He recounted one such occasion: “a mass meeting to ‘free the women.’ It was held in an auditorium and was attended by a thousand workers—all men of course—because who had ever heard of bringing women to a meeting on a Thursday evening?”

[adblock-left-01]

The Orrs had time for an occasional day off. They both enjoyed Eileen Blair’s warmth and good humor, and one Sunday they went for a picnic in the country with her and an Italian friend. “At the office,” wrote Charles, “Eileen just could not resist talking about Eric—her hero husband, whom she obviously loved and admired. It was my privilege to hear about him day after day. Not that I paid much attention. He was still just an unknown would-be writer who, like others, had come to Spain to fight against fascism.”

As this little group of foreigners was getting to know one another, political tensions in the city were rising. This was a matter, as Orwell put it, of “the antagonism between those who wished the revolution to go forward and those who wished to check or prevent it—ultimately, between Anarchists and Communists.” To believers like the Orrs, the Spain that promised an anarchist millennium was receding from sight.

Meanwhile, tension increased on another score. The Republic was urgently trying to build a national army under strong central command to replace the half-trained hodgepodge of militia units loyal to different political parties and trade unions. For all its allure, the kind of egalitarian, exuberant defiance of authority that made the infant Spanish Revolution so attractive to its admirers had never been one of the building blocks of a strong army. With the revolution-minded anarchists and the POUM on one side and the increasingly powerful Communists and their mainstream allies on the other, conflict within the Republic mounted through early 1937.

“I felt,” wrote Lois, “as if I were living in a powder-keg.”

The anarchist stronghold of Barcelona was where the Spanish Republic’s internal civil war reached its breaking point. The final trigger was a series of telephone calls.

The red-and-black anarchist flag had flown for months over the city’s telephone exchange, a triumphant symbol of revolutionary power because the building had been seized from the American-owned International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation. On May 2, 1937, a Republican cabinet minister tried to telephone an official of the Catalan regional government, only to be told by the anarchist operator that there was no such government—the anarchist dream—only a “defense committee.” When the Republic’s president called the president of Catalonia the same day, an anarchist operator broke into their call and insisted that they stop talking. Officials were furious, and Catalonia’s security minister ordered the police to take over the exchange building. The anarchist guards were armed, and firing began.

“The shots frightened clouds of birds into the grey overcast sky,” Lois remembered, “and sped word through the city: IT had finally begun.” This was the decisive showdown over just who would control Spain’s second-largest city and indeed the whole northeastern part of the country.

Lois was sick at home that day. The moment the fighting began, however, she was out of bed. “10 minutes after she heard about it, she was out with me helping build barricades,” Charles wrote proudly to his mother. In less than a week, the Barcelona street fighting, a war within a war, took several hundred lives. “I am an expert now,” Charles reported. “[W]orked on 5 or 6 wounded and 1 killed in my principle [sic] station. My neck was grazed. But it would be worth dying for. … We are quite o.k.—a little hungry. The fighting is evidently finished—but no one has won.”

He was wrong about that. The Republic’s government had won, establishing its rule over the city and region. Anarchist leaders ordered an end to armed resistance. Militant to the end, Lois had nothing but contempt for what she regarded as a surrender. After months with few customers, Barcelona’s hat shops suddenly found business booming. By June, the Orrs noted another sign that the old ways of life were returning. They found their electricity and hot water turned off. “I’m writing you by candle light,” Charles told his mother, “because the Electric Co. tried to make us pay for the German Consul’s bill. We offered to pay our part since Feb. 15 even, but they wouldn’t bargain. So—no more hot baths.”

The Spanish Republic’s internal security apparatus was now dominated by Soviet advisers. They had no love for Spain’s anarchist movement, but the far smaller POUM was a particular object of Stalin’s wrath because it had broken off from the world communist movement and one of its leaders had for a time been close to Stalin’s archenemy, Leon Trotsky. Indeed, the POUM’s newspaper had been virtually alone in Republican Spain in attacking the mass arrests and show trials now under way in the Soviet Union. This was heresy, and POUM supporters in Spain, like the Orrs, feared that they might feel the consequences.

At 8 A.M. on June 17, 1937, four men in uniform, one of them a Russian, and four plainclothesmen from the Republic’s military intelligence service arrived at the Orrs’ front door and “showed us,” Lois later wrote, “a floor plan of our apartment and a list of everyone who had lived or even visited there.” They arrested the couple and seized all their letters, journals, and other possessions. More than half a century later, when some Soviet intelligence files on the Spanish Civil War years were at last opened, it was clear that the Orrs had been under close surveillance, enough so that agents knew Lois was more militant than Charles. “Her fanatical approach to various political issues,” reads her file, “was particularly striking during her work in Barcelona.”

The police station to which the couple was taken was so crowded that some prisoners were left sitting in stairwells. Charles recognized both Spanish POUM leaders and anti-Stalinists of various stripes from other countries who had been part of their circle. A hundred prisoners were crowded into a cellblock with only 35 cots and were fed two bowls of soup and two pieces of bread a day. Bedbugs crawled the walls.

Shortly thereafter, Charles, Lois, and some 30 other foreigners were marched at midnight through narrow streets illuminated only by the flashlights of their guards to what had once been a local right-winger’s home. The servants’ quarters had been converted into cells. “Stalin’s terror was at its height,” Lois wrote. “Some loyal [S]talinist had drawn on the wall of our room a beautiful map of the Soviet Union, lovingly detailed with mineral deposits, industrial centers, mountain ranges and tundras. The men told us their quarters had a big picture of Stalin on the wall. These carefully executed wall drawings brought me much too close to the horror of the Moscow Trials, where you cravenly protest your love and faithfulness to those who falsely accuse and then murder you. Would I come to that?”

Lois tried to keep her spirits up by taking language lessons from a German cellmate and learning dress design from a prisoner from Poland. “They called me ‘the baby’ because my life story was so short, and mothered me kindly. … We sang every day. French, German and even American songs from our room joined the far-off songs from the other cells.” It did not help her morale to notice in a Communist newspaper—all they were allowed to read—that the POUM was accused of being part of a Nationalist spy ring.

“Such unbelievable lies,” Lois fumed, “and about me.”

The several dozen POUM officials, anarchists, and other non-Communist leftists who died in the prisons run by the Republic’s intelligence service were largely Spaniards. Many foreign sympathizers of the POUM and the anarchists were soon released. This is what happened to Lois and Charles, who after nine days in custody found themselves abruptly let out onto a Barcelona street at four o’clock one morning. A few days later, they were on board a ship for Marseille. Their 10 months in Spain were over, as was the experiment in social transformation they had come to join. As they went below decks to eat their first meal in the ship’s dining room, Lois felt she was “at a wake.”

The couple lived in Paris briefly, then returned to the United States. Their differences in temperament already had been visible in their responses to revolutionary Spain, and after having a child, they divorced. Charles had a long career as an international labor economist; Lois worked for a time as a union organizer, remarried, had two more children, and finally became a Quaker and an activist in the Waldorf Schools movement. Her nine and a half months as a newlywed in Barcelona remained a highlight of her life. Over the course of more than 35 years, she wrote many drafts of a book about her experience in Spain, which never found a publisher. A selection of her correspondence from that era did not appear until long after her death at age 68, and then only in a small printing in Britain.

After mid-1937, the remaining vestiges of worker control were largely suppressed. Although the Spanish Civil War continued to intensify, finally ending in 1939 with Nationalist victory and the beginning of Franco’s 36-year dictatorship, the Spanish Revolution had been brought to an end. Was the enthusiasm for it of someone like Lois Orr justified?

It is easy to see why this political moment had such enormous appeal. Idealists had long dreamed of a world where wealth would be shared, workers would own factories and peasants land, while democracy, in yet-to-be-defined ways, would be far more direct. For some months, much of this had actually happened, above all in Barcelona, surrounding Catalonia, and nearby Aragon. Imagine a sweeping revolution in the United States centered on Chicago, including all of Illinois and Indiana. The huge changes were deeply tarnished, of course, by thousands of killings. But it is still hard to find an example, before or since, where so many ideas normally considered utopian were put into practice on such a large scale.

The world the anarchists imagined would have been hard enough to sustain in peacetime, much less in the midst of a backs-to-the-wall war against an army supported by the Nazis. Nonetheless, doomed though the Spanish Revolution may have been, for a matter of months a stunningly different kind of society grew and flourished. And in our world of growing economic inequality, the Spain of 1936–1937 offers an intriguing example of a path not taken.

Someone outside the country trying to learn about this while it was happening, however, would have had a tough time. Even though the Spanish Revolution took place amid one of the largest concentrations of foreign correspondents on earth, they seldom wrote about it. Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, and the glamorous array of other well-known writers and journalists who reported from Spain during the war flocked to cover the major battles. But if you search the American and British press during these years, for every thousand articles about ground gained and lost on the battlefield or about the bombing of Madrid, you are lucky if you can find one that even mentions the way Spaniards briefly wrote a new chapter in Europe’s centuries-old battle between classes. Not one of the nearly 1,000 correspondents who reported from Spain bothered to spend a few days in a Spanish factory or business or estate taken over by its workers, to examine just how the utopian dream was faring in practice.

“It didn’t seem possible,” Lois Orr said of the correspondents, “that they were describing the same Spain I was in, the one located on the Iberian Peninsula.” Has history ever seen a case where such a huge array of talented journalists ignored such a big story right in front of them? The most extensive record by any American of this revolutionary moment remains in the letters and unpublished writing of a 19-year-old who had gone to Europe for her honeymoon.