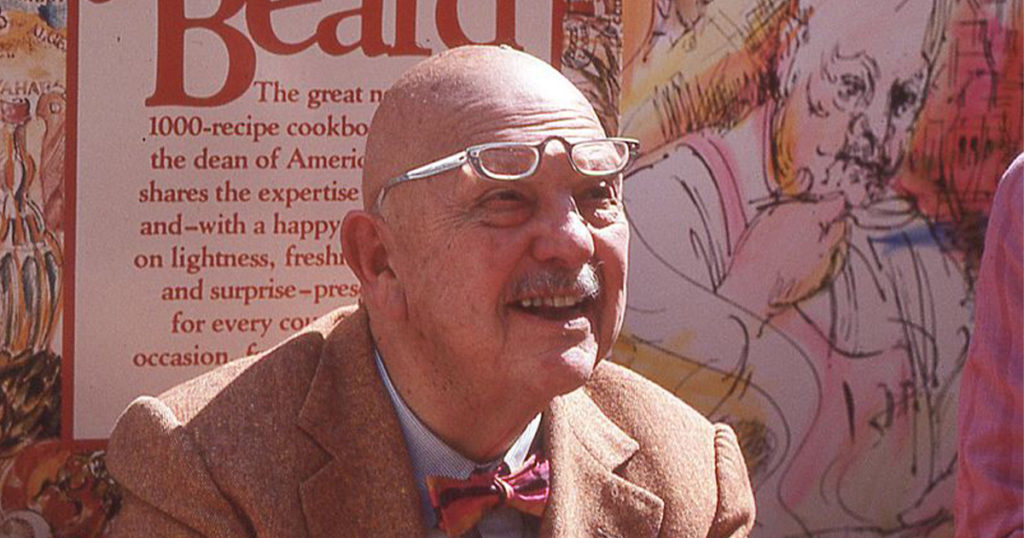

The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard by John Birdsall; Norton, 464 pp., $35

James Andrews Beard (1903–1985) was 310 pounds of blazing appetite—for money, for applause, for butter, for more butter. He wore jaunty bow ties and striped aprons. He played with his food, plunging huge hands into whipped egg whites with Rabelaisian glee. He dreamed of a life in theater, but instead invented the television cooking program and the gourmet hamburger.

He invented the noted epicure, too. Beard had a phenomenal taste memory—the culinary equivalent of perfect pitch—but no formal training, Yet by 1946, he was on NBC, impersonating to perfection the bachelor uncle who makes good food fun; a chance, he said, to cook and act. The postwar nation craved culture made painless. Readers Digest Condensed Books, light classical, paint-by-number. Art spreads in Life magazine. Itzhak Perlman and Marian Anderson on The Ed Sullivan Show. Beef stew, French peasant-style, with jolly James Beard.

Who was gay.

The price of that hidden identity powers this subtle, surefooted biography, the first in 25 years, of an American Bacchus ripe for reassessment. Birdsall reminds us that Beard “occupied a curious persona that combined decorum with total self-indulgence,” and that tension yields a splendid, disturbing portrait of a character out of Dreiser—or Twain.

Caught in flagrante with a faculty member, Beard was expelled from Reed College in his native Portland, Oregon. He failed at grand opera and theater, flopped in Hollywood (except as a Cecil B. DeMille extra), taught high-school social studies in New Jersey, then catered party food for the discreet salons that fueled Manhattan’s gay socializing. After global war made culinary isolationism stale, Beard seized the moment, hard. But lives devoted to beauty seldom end well, as The Man Who Ate Too Much proves in succulent detail.

Beard, at his best, was both pioneer and seer. He was an early advocate of farm-to-table eating. As design adviser for the Four Seasons and menu consultant at Windows on the World, he invented new vocabularies of sensual surprise. He was fortunate—very—in the army of women who ghostwrote his projects, edited his rambling prose with crisp authority, tested hundreds of recipes, and briskly de-queered him (what Birdsall terms “the cleaning and polishing of James into a commercial entity”) when homosexuality risked jail, disgrace, and career suicide.

A sanitized Beard built a multiplatform brand through ads, magazine pieces, brochures, cookbooks, lectures, and cooking demos. Waiting lists for his classes were soon years long (though, he noted, “there have been a few students for whom I would not have wept had they mistaken a flagon of hemlock for the aperitif.”) He knew his role: smile, shout “I love to eat!” and sell, sell, sell. He shilled for Birds Eye, Benson & Hedges, O’Quinn’s Charcoal Sauce, General Mills, Borden’s, Pernod. He once did a grilling cookbook for a blowtorch company. He bought a Greenwich Village townhouse, and kept a mentally ill ex-lover in an upstairs apartment for decades.

Beard could be delightful company. He could also be a monster. Exploiting the powerless bothered him not at all, and due credit was an alien concept. He swiped or self-plagiarized a shocking number of recipes. Feuds, coteries, vengeances, seductions and cruelties peppered his days. When the rules of gay life began to change (1969’s Stonewall riot occurred blocks from his home), Beard was frightened, and adrift.

This compassionate study in passing and evasion grew from the author’s essays on LGBT aspects of culinary culture, particularly America, Your Food Is So Gay (2013), a takedown of macho swagger in the professional kitchen and defense of cooking “calibrated for adult pleasure, acutely expressive of a formalized richness—exactly the type of thing James Beard taught Americans to eat … unflinchingly, unapologetically, magnificently queer.”

Birdsall, whose Twitter ID is “Pushing back on queer erasure in American food,” is an accomplished writer with long restaurant experience as line worker and as critic. He is good at avoiding pathography, terrific at interviewing the dead. What did it feel like, look like, to be there then? The result is a marvel of narrative nonfiction that achieves for 20th-century gay history what Tom Wolfe did for aviation in The Right Stuff, a subjective and objective reconstruction of a neglected American subculture hiding in plain sight.

Birdsall also restores Beard’s identity as a man of the Pacific Rim, raised by a gay mother and a Chinese cook in a town where the Yukon was still a real frontier. Like other restless, sexually complex modernist talents (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Cather), Beard craved urbanity and needed decades in exile to see that his natal terroir—Chinook salmon, Olympia oysters, razor clams, marionberries, green fields in fog—held the key to his life and career. A 1954 auto tour of the West Coast, during which he bought so many samples that the car became “a mad ark of food,” finally focused Beard’s instinct for a true American cooking. Thirty-one years later, his ashes were scattered at the Oregon beach he loved in childhood.

Beard wanted to disappear upon his death, with all traces of his secret self erased, but Julia Child and other friends preserved his West 12th Street townhouse as a foundation and education center, and instead he became a culinary saint. Though his complete daybooks for the 1950s survive at New York University, a great stroke of documentary luck, much personal material was destroyed, and nearly everyone who knew him is gone. But a novelist’s eye—the “apple-green limousine” of an early Beard patron—and a historian’s archival stamina let Birdsall reveal a milieu, and a soul.

A warrior, too. Beard, subversive and outsider, became a general in the fight against bad fancy food, the kind that Beard Award winner Calvin Trillin dubbed La Maison de la Casa, Continental Cuisine, whose menu “will sound European but taste as if the continent they had in mind was Australia.” Respect for American provender flourished well before Beard monetized it: from 1940 on, Richard Hougen made Boone Tavern in Berea, Kentucky, a regional showcase. And when Beard was a newbie pushing salami canapes, food editor Ann Batchelder of the Ladies Home Journal—a lesbian and feminist, with a blacklisted lover—had championed fresh, simple, local, delicious, for a generation.

An army of citizen-eaters eventually heard them all, and started chopping. “The best and most interesting food in America was inseparable from the landscapes that produced it,” Birdsall’s Beard realizes, with the force of revelation. “It was all right there, in country diners and small-town grocers’ shops; in roadside dinner houses and bakeries. All you needed to do was look.”

John Birdsall was a guest on our podcast, Smarty Pants, on October 2. Listen to the episode here.