A Portrait of the Scholar

The life of Ireland’s towering literary figure became a work of art in its own right

Ellmann’s Joyce: The Biography of a Masterpiece and Its Maker by Zachary Leader; Belknap Press, 464 pp., $35

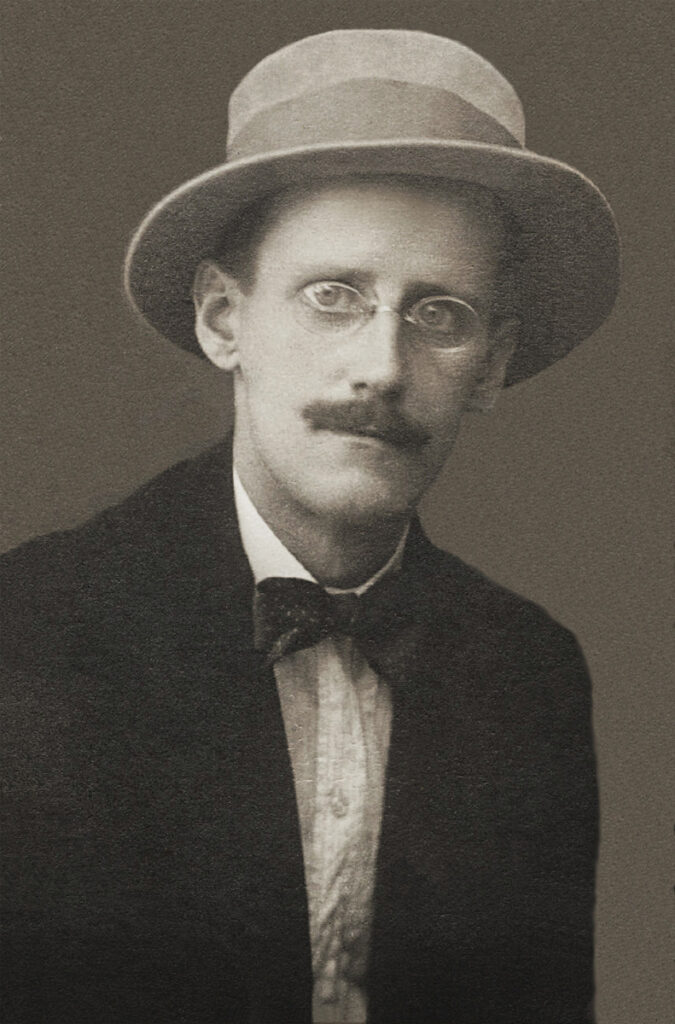

Does biography illuminate the work of an artist? James Joyce slyly poked at this age-old question in his 1922 novel Ulysses. In one of the book’s many meandering scenes, Stephen Dedalus and a group of literary associates banter at the National Library of Ireland. Stephen spins out his theory that various characters in Hamlet stand in for Shakespeare himself. Yet Joyce gives the episode’s best line to another character who regards interest in writers and their lives as an unseemly distraction: “Peeping and prying into greenroom gossip of the day, the poet’s drinking, the poet’s debts. We have King Lear: and it is immortal.”

Ulysses is immortal as well: brilliant, infuriating, hilarious, unfathomable—an unrivaled colossus of modern literature. Who could write such a novel? An English professor at Northwestern University named Richard Ellmann undertook to find out and in 1959 published James Joyce, which one critic hailed as “the greatest literary biography of the twentieth century.” But who was Ellmann? And what is the story behind James Joyce, the rare biography that, like Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson or Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, breaks free of its subject and attains the status of literature?

Only a master biographer could hope to answer such questions. Zachary Leader fits the bill, and Ellmann’s Joyce takes readers on a dazzling intellectual tour. The book is not Leader’s greatest accomplishment: his two-volume life of Saul Bellow and his celebrated biography of Kingsley Amis take up more weight on the metaphorical shelf. Nevertheless, Ellmann’s Joyce is a singular achievement worthy of notice, both in its exploration of character and as a defense of the biographer’s art.

Ellmann first considered writing about Joyce while working on his doctoral thesis after wartime service in Europe. While visiting Ireland, he asked William Butler Yeats’s widow whether Joyce had really insulted her husband when they first met by telling him, “You are too old.” Joyce at the time was 20, and the great poet nearly twice his age. Both men had denied the remark, but Mrs. Yeats showed Ellmann an unpublished essay in which her husband had committed it to print. “As all mild men must [be], I was delighted by this arrogance,” Ellmann would recall. The encounter reveals his knack for getting people to talk, as well as the thrill of discovering a primary source.

Blessed by Northwestern to undertake the Joyce book, Ellmann set off in 1953 to chase leads through Dublin, Paris, Trieste, and Zurich. Joyce had died a dozen years earlier, but Ellmann spoke with everyone he could find who had known the writer. One observer of Ellmann at work said he made it his practice with interviewees “never to contradict, scarcely ever to interrupt. He let them talk; he showed himself grateful for what they told him; now and then with a quiet question he would elicit some particular point of information, and in leaving would express his thanks again. He left them smiling and thinking, what a nice young man!”

Yet Ellmann’s obliging manner concealed ambition, competitiveness, and occasional sharp dealing. He eyed rival Joyce scholars and angled to secure exclusive access to papers and documents. A talented flatterer, he cultivated sources with ingratiating notes and gifts. On one occasion, he charmed an old friend of Joyce’s out of his prickly reticence by publishing a favorable review of the man’s book. Ellmann’s diplomacy paid off most spectacularly with the discovery of more than 100 letters between Joyce and his brother Stanislaus. Yet another widow was involved; the letters lay gathering dust in a cellar. “I had tumbled into King Tut’s tomb,” Ellmann later wrote.

Biographers often make the mistake of saying too much rather than too little. Yet Leader, who has written an admirably brisk book, might have elaborated on why these particular letters were such a bonanza. As James Joyce reveals, James and Stanislaus had an edgy relationship full of codependency, resentment, and blunt talk. Ellmann quotes a 1924 letter from Stanislaus, written when Ulysses had become a sensation. Instead of adding to the hosannas, Stanislaus lamented the obscure turn in his brother’s prose, noting that it seemed “written with the deliberate intention of pulling the reader’s leg” and asking pointedly, “Why are you still intelligible and sincere in verse?” Then again, perhaps one of the pleasures of Ellmann’s Joyce is sending readers back to James Joyce to discover such passages for themselves.

If so, fair game. James Joyce overflows with riches, including, Leader wryly notes, vigorous writing at the ends of chapters: “sites of drama and suspense.” Not long after receiving his brother’s letter, an ailing Joyce pressed on with his final book, Finnegans Wake, earning this stirring peroration from Ellmann:

So, in spite of pain and sporadic blindness, Joyce moved irresistibly ahead with the grandest of all his conceptions. No ophthalmologists could seriously impede him. Through blear eyes he guessed at what he had written on paper, and with obstinate passion filled the margins and the space between lines with fresh thoughts. His genius was a trap from which he did not desire to extricate himself.

Such flourishes excited general readers but put off certain academic critics. As Leader explains, James Joyce has its share of detractors—for its narrative structure, glancing engagement with Irish politics, conflation of Joyce and Stephen Dedalus, and what one scholar called its “rather mediocre” stabs at literary criticism. Yet the book proved a sensation on its release, earning broad publicity for Oxford University Press and winning the National Book Award.

Ellmann’s Joyce is not limited to the story of a single volume. Leader’s Ellmann is a man in full: a midwesterner, a Jew, a teacher, and a loyal son whose loving father wrote him long, almost comically interfering letters. Most haunting is Leader’s sensitive exploration of the sacrifices Ellmann’s wife, the scholar Mary Ellmann, made for her husband’s career. “I cannot bear it. I feel myself being destroyed,” she wrote in one devastating note about domestic tedium. On the eve of the family’s move to England in 1969—she did not want to go—Mary suffered an aneurysm that left her in a wheelchair. In presenting Ellmann’s story, Leader does not scold or editorialize; instead he recounts a life in prose that is authoritative, compelling, and true.

James Joyce demystified a towering artist for many an intimidated reader. Joyce, we learn, loved his family, scorned Ireland, fought censorship, lived in poverty, feared cuckoldry, suffered poor health, and sang beautifully. Though his novels and stories stand on their own, his biography is by no means irrelevant. It shows how life becomes art. Nothing in the world could be more interesting. Leader transposes that same fascinating process onto Ellmann: scholar, literary detective, and writer. Between Joyce’s books, Ellmann’s biography of Joyce, and now Leader’s work on Ellmann, readers have a unique nesting doll of literary treasures. The only question is, what to read first?