Last March, when the pandemic threatened and the lockdown began, I thought of all the spare time I would have. New Yorkers love to boast about how busy they are, a dubious point of pride. Among friends, subtle competitions can simmer, everyone seeking to be Busier Than Thou. But with all of us working from home or out of work, a peculiar unease arose: instead of having no spare time, could we have too much?

I had just completed writing a book and wasn’t ready to start another. My teaching job, now online, was part-time. Acres of time unfurled before me—what I had always longed for—yet I found myself slightly alarmed at the prospect. No work deadlines, no visits with friends, no theaters or movies, no museums. Even my weekly volunteer work was canceled. There was always walking and reading, but … what else would I do?

This was obviously the moment to start projects there’d never been enough time for, and I don’t mean cleaning out closets. (One of my daughters once remarked that whenever I finished a book I started cleaning closets.) But I wanted to use the time in a more productive or, at any rate, more enjoyable way.

I have no talent for the visual arts, nor had I ever ventured to learn. Everything I knew how to do was connected to music (piano and West African drums) or to language—reading, writing, translating. All my life, I realized with creeping dismay, I had stuck to those pursuits and avoided learning anything unfamiliar, anything that did not come naturally. Even in college, I had contrived to take only the minimum of required courses in other areas. In a manner of speaking, I had never learned anything new—that is, anything that would train my mind to move along new pathways.

One thing I had always had a yen to do, though, was to make collages. Surely anyone, even without artistic talent, could cut and paste. And I had a fairly good eye: I could tell original from banal, pleasing from clumsy. Not that what I made needed to be original or even pleasing. Unlike with my writing, I was not seeking an audience. What better time?

I dug up a shopping bag full of scraps of leftover wrapping paper, which I’d been saving for such a project when I had free time. I bought some large poster boards and glue sticks, spread newspapers over the dining room table, and got to work. My first effort was meant to represent the painful experiences of immigrants at the border crossings in Texas, an awful situation that was getting worse. From old Christmas wrapping paper I cut out figures of children; from colored construction paper I made a long wavy blue strip to represent a river and a bland beige shape to represent the desert. This and more I pasted on varied shapes of colored paper. The finished product had no artistic value whatsoever and probably couldn’t be understood, but I’d loved doing it. I showed it to my family, like a child proudly bringing home a kindergarten project, and though they were kind, they were puzzled. To make my theme absolutely clear, I added words in caps: RIVER; DESERT; FENCE; BORDER GUARDS. I sprinkled the whole thing with letters that spelled CRUELTY.

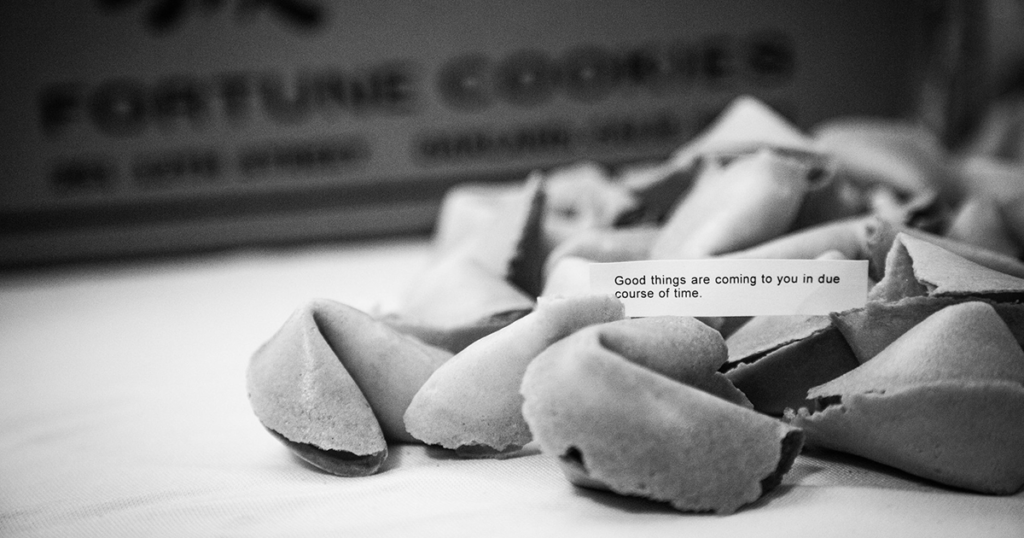

So even my “artwork” couldn’t escape words altogether. My powers of visual expression weren’t enough. Then I remembered my large collection of Chinese fortune cookie sayings, which I’d been saving for years. I loved the amusing clichés that everyone reads after dinner in a Chinese restaurant. (“You are soon going to change your present line of work.”)

I decided to assemble a large collage of my collection, with the fortunes pasted onto colorful backgrounds. To start, I typed them all into a document and chose a different typeface for each one, enlarged enough to be readable from a few feet away. I was amazed at the dozens of exotic fonts my computer offered; if I ever wrote anything again, I thought, I could use them to liven up my manuscripts.

I cut them all out and then cut out a bunch of oddly shaped backgrounds of construction paper, and painstakingly assembled the whole work. (“Any job, big or small, do it right or not at all.”) I wanted a haphazard look, which it definitely had: no familiar geometrical shapes, no discernible order, just cheerful chaos—a freedom I could never exercise in writing or music, where I knew too much. In this field I knew nothing, no tradition to aspire to, no models to emulate. No public would see or judge what I had done. I knew that great artists had made collages, but those were so remote from my efforts that I didn’t even consider them. (“Never compare yourself to the best others can do, but to the best you can do.”) I could do whatever I wanted. I was thrilled with the result. It turned out that over years of Chinese meals I had collected too many fortunes to fit on a single three-by-four foot board, so I went through the whole process again.

Now I have the two posters decorating the walls of my study, and when I look up from my desk I can take courage from “Focus on the main task at hand” or “You are offered the dream of a lifetime. Say yes!” But there was one that I disobeyed: “Depart not from the path which fate has you assigned.” At long last, I had departed from the path that fate assigned me. I tried something I had no innate aptitude for. I learned what it is to learn.