In 1971, my parents purchased an 1890 white clapboard schoolhouse in Canton, New York, for $1,000. Abandoned and sitting alone on an acre of land, the building was falling apart. They set to work making it habitable, welcoming my sister in 1972, when the floors were still dirt, and bringing me home there from the hospital in Potsdam in March 1975. Two years later, we moved away, but if Gaston Bachelard is right that our first enclosures disproportionately inform the architecture of our psyches and our capacity to dream, then my own mind was formed in the shape of that house.

Is that why Robert Adams’s photograph Catholic Church, Winter, Ramah, Colorado, 1965 seems strangely familiar to me? The picture is centered, sturdy, black-and-white. Our schoolhouse was less symmetrical than Adams’s church, but it shared a blunt simplicity: white horizontal boards stretching up to a peaked roof capped with a belfry in one structure, a steeple crowned by a cross in the other. One was a discarded, secular building in upstate New York, the other a functional religious sanctuary in a small Colorado town (the population of Ramah was 130 as of 2020). The same and different, the buildings say something about American society, rural poverty, children, and the universal need to seek shelter of one kind or another.

Both buildings stood in deserted but not desolate landscapes. Both had the company of some large trees. In the snapshot I have of my first house, piles of half-chopped wood stack against the front door while a block of dirty snow squats in the yard under a window, along with a garbage can, a shovel, and what might be a tire. In Adams’s picture, you can discern the edges of metal tanks and a play structure in the background. In both photos, electrical lines cut into the picture from beyond, tenuous links to power or to the wider world. At the church in Ramah, a tiny lantern by the door seems insufficient for the task of casting light or dispelling darkness. At the schoolhouse in Canton, a lone bulb dangles over the peaked doorway, reminding me of the lightbulbs in Philip Guston’s late paintings: cartoonish and desperate. In both photographs, bleak tree limbs bereft of buds or leaves intensify winter’s cold light.

Catholic church, Winter, Ramah, Colorado, 1965

The light makes all the difference. Adams also photographed the church from this same perspective in the summer, when it appears oddly larger, its mass pushing outward, framed by leafy trees and billowing clouds. But here, the wintry light becomes its own subject, and an almost terrifying clarity makes me think about religion and the supposed demarcation between the saved and the damned. One side of the structure glistens in pure white, while the other side is bathed in a shadow that darkens as it stretches out along the ground and up into a grove of trees in the background. The picture presents a startling either/or: either the subdued window to the left or the illuminated one to the right; either the dark side of roof with its slightly askew exhaust pipe or the pristine slope of roof opposite. A tree, some grass, the metal tanks, the playground, and the power lines all align with the side of the church in the sun, as if life itself gathers in one quadrant.

Adams was born in 1937 in Orange, New Jersey, and he has spent much of the past 50 years making photographs of the prairies, forests, and beaches of the American West—depicting loss and degradation in these formerly pristine landscapes as well as capturing people midstride, mid-embrace, or lost in thought. Adams has also written extensively about photography, stressing its spiritual dimensions and its ability to instill what he calls “affection for life.” I am less religiously minded than Adams, but I was raised going to Sunday school, and I appreciate—even if I don’t believe—the clarity of religious doctrine in a world that so often feels ambiguous and ill-defined. It would be simpler to live in a black-and-white world where the doors one should open are bathed in sunlight. But it’s never that easy. One thing I love about Adams’s picture of the Catholic church in Ramah is that the illuminated side of the door has no handle.

Longer looking reveals a world of mixed messages. Shadows interrupt form, casting bent and irregular shapes. The church is elevated on a concrete foundation. Why? Was it built in a floodplain? Was it raised to be closer to heaven? Was it depicting the etymology of Ramah from the Hebrew word for a height or high place ? How would someone with a cane or in a wheelchair navigate the steps? Could a wedding party assemble to throw rice? Could a funeral procession haul a coffin up or down? The structure resists entry or exit, accentuating the sense that either you’re in or you’re out.

The River’s Edge, 2015

Then there is the cross, a perfectly even gray against the midtone sky. It seems large for the building, as if someone miscalculated the dimensions or just got carried away. I like the clunky feel of it and the way the top recedes almost into thin air. Unabashedly astride the roof (but tipping ever so slightly to the right), it gives the whole building a sweet, goofy sense of importance.

The picture, like so many of Adams’s photographs now on display in a retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is quiet but tense. Something is happening, only not where we can see it. We know from the date in the title that the picture was taken at a significant historical moment. Among other things, 1965 saw the Voting Rights Act signed into law, the escalation of the war in Vietnam, and the assassination of Malcolm X. But the photograph remains neutral. Here and elsewhere, Adams achieves what Simone Weil said she aspired to—namely, “to see a landscape such as it is when I am not there.” What was happening in Ramah in 1965? Perhaps people were gathered and singing inside—a tempting counterpoint to the stoic, silent feeling of the photograph. Maybe it was a weekday, and the church remained quiet and locked. Maybe it was abandoned, and no one went there any longer to pray (that seems unlikely). I remember arriving late to church as a child, when the doors were already closed, and it wasn’t clear whether one should enter or leave. I would stand outside and listen. I keep looking at Adams’s picture and expecting to hear something.

Unlike my childhood schoolhouse, with its littered yard and confused light, the church testifies to a symbolic order. Order is one of Adams’s recurrent obsessions. Even in the most desolate landscapes, Adams believes that photographs retrieve what he calls “a mystery at the end of every terror—the survival of Form.” The order of light and shadows, the order of geometry, the brute forms of humanity against the intricate and organic chaos of nature. A riot of branches on the dark, left side of the photograph reads like inky scribbling against the flat sky. Countering the simplicity of the building and the organization of Catholicism, those branches seem to murmur, Things are complicated.

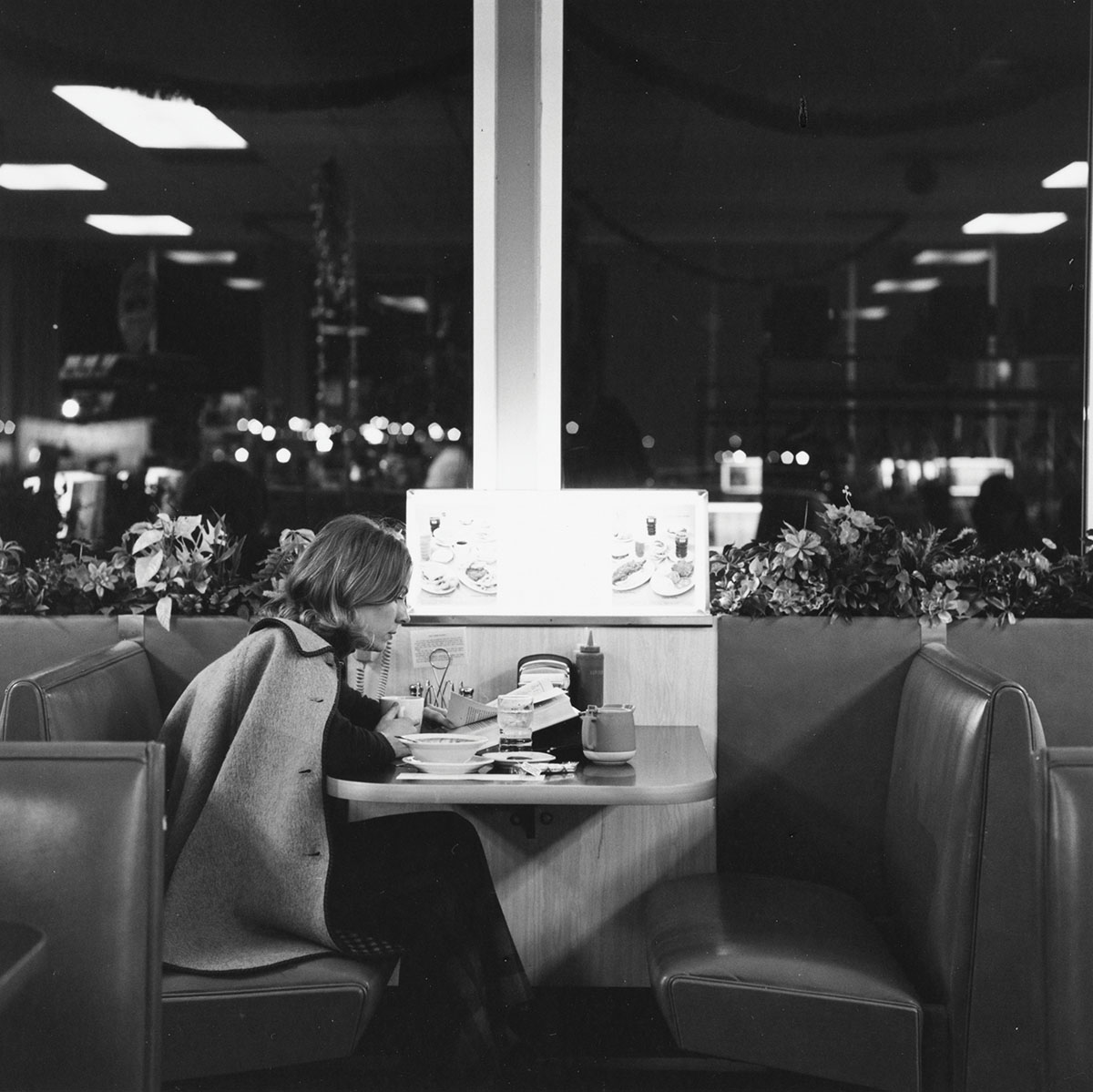

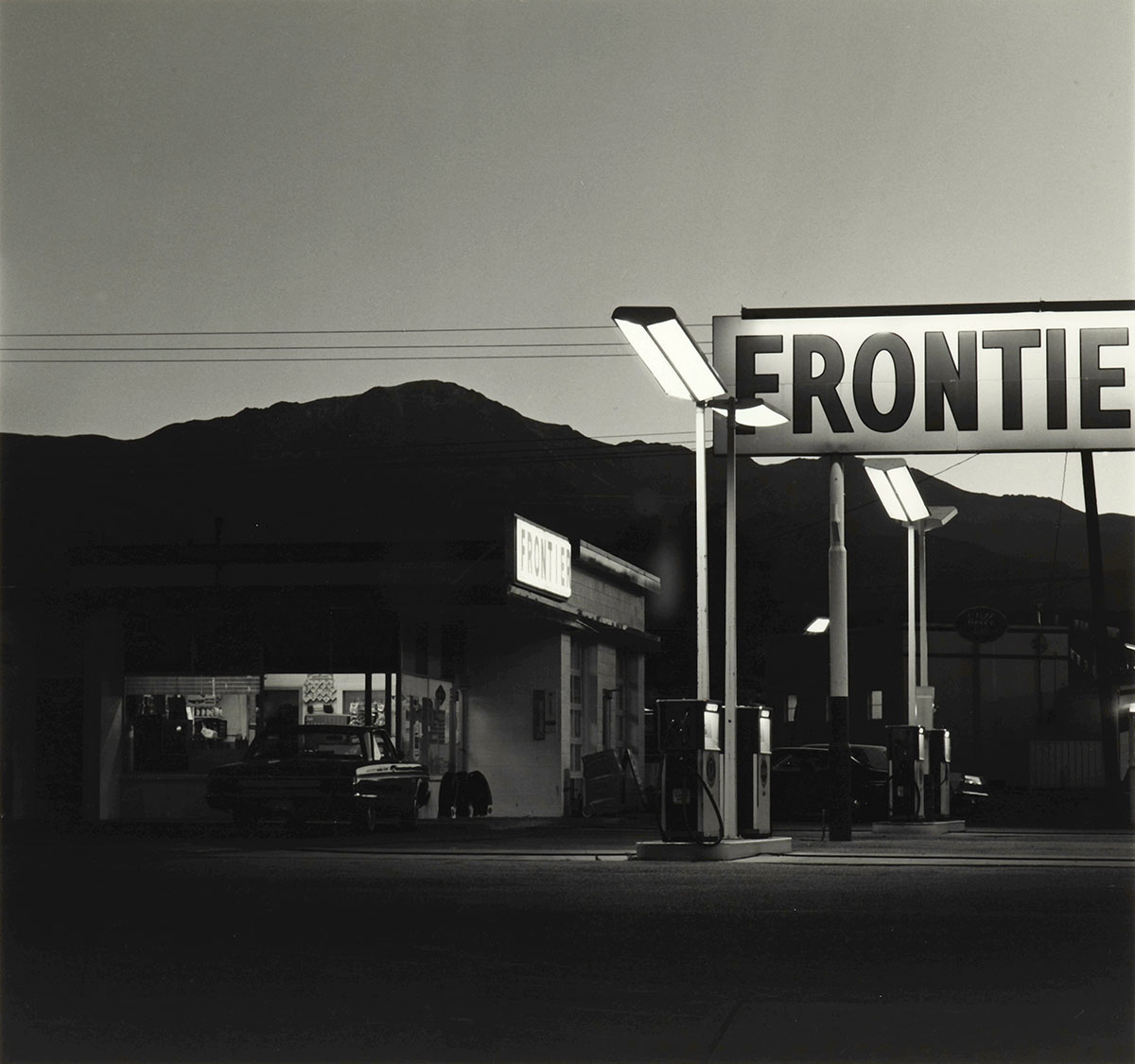

Longmont, Colorado, 1973

There is something poignant about the human drive to create order, in part because it feels like a losing game. You build and sweep and clean only to have to do it all over again. W. G. Sebald described the scene in Germany after the Allied bombings in 1943, both the destruction and the surreal efforts to go on: “The population decided—out of sheer panic at first—to carry on as if nothing had happened.” He described one young woman who was methodically cleaning the windows of a building that had remained unscathed, alone amid a “desert of ruins.” It is mad—but human—to order things in the face of catastrophic disorder. As I write, in the spring of 2022, we are seeing pictures from Ukraine of people moving through the debris of their lives. In the early days of the war, a Ukrainian woman who had just witnessed the bombing of a building told a New York Times reporter, “It is very painful to watch a building come down. It is not only a building; it is our life.”

I think Adams liked the precarious, almost stage-set feel of the clapboard prairie buildings he photographed in the 1960s—at a time when he was in the first blush of his love affair with photography, more attuned to the hopefulness of architecture than to the despair of environmental degradation. The little church in Ramah represents a form of life. It is trying so hard to stand steadily there in its place, even as its pipe, its spindly banisters, its cross, and the peeling paint around the central windows show vulnerability to weather, to age, to time. Adams captures that melancholy sense of a fragile, fallible faith. The building epitomizes the tensions in being human: the effort of standing, the risk of collapse. It radiates a quiet dignity that seems slightly absurd, given its surroundings. But that absurdity feels as close to being human as anything else. It is remarkable that the picture retains its sincerity 57 years later. Faith remains a mystery.

There are rarely people in Adams’s work from the 1960s. But we are disclosed in our debris, whether we like it or not. Perhaps that is why, in looking at these photographs, I was shuttled back to my past and to the material reality of where I was born. These sites are inscribed in us, and when they are in ruins, we feel ruined too. Adams makes us care about places we have never been, in part by stirring memories of the places that cared for us. Across the country, a child I will never know was swinging behind the clapboard church in Ramah while I was crawling on the plywood floor in Canton, both of us caught in the shadows and the light, both of us made of the same stuff.

Can you remember the child’s game of intertwining your fingers to make a church, raising your pointers for a steeple, and opening the doors (your thumbs) to “see all the people”? Adams reminds us that we don’t always need to open the doors. People are there in their structures, in the churches, cars, signs, houses, strip malls, and even in the junk and scattered stumps they have left behind. Presence in absence can be haunting, but hopeful. It can help us to feel that we are not alone, even when things are falling apart and there is no one in sight. In his book Art Can Help, Adams, thinking about towns no one visits anymore, quotes the following fragment from the poet William Stafford: “space, and the hurt of space after the others are gone.” Nothing lasts forever. Thank goodness Adams made pictures so that we can recall vanishing places and gather in the hurt of space, waiting for someone to ring a bell.