A Song for Molly

In which I tell how I fell hard for a dog, why I have problems with women, and what I know about Ludwig Wittgenstein

The world is everything that is the case. —Ludwig Wittgenstein

Why can’t a dog simulate pain? Is he too honest? Could one teach a dog to simulate pain? Perhaps it is possible to teach him to howl on particular occasions as if he were in pain, even when he is not. But the surroundings which are necessary for this behavior to be real simulation are missing.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein

Chapter 1

This morning I walked to a nearby coffee shop run by an Asian couple who speak a language I don’t recognize. It has a large picture window, where perched on a stool I observe the passersby. An elegant woman stops on the sidewalk outside. At her feet is a small brown dog. I cannot help but wonder about their relationship. How do they communicate?

The first time I traveled to India, an Indian friend told me that each day I would see something I didn’t understand. The same is true for women. They are always doing things I don’t understand, and I’ve found there’s no use asking them to explain themselves. It would be like trying to explain the color orange to someone who is colorblind.

The woman sits down on a bench in front of the coffee shop and dissolves in tears. A curious verb in this context—dissolve. If tears could melt, this poor woman would have melted. Seeing women cry breaks my heart. My mother cried once. My father had told her that we had to change cities because of his job. We would be leaving the house into which she had poured her love—the garden and the living room with its custom sofa too big to move. I was 10 and stood outside the door listening to her cry. I would like to comfort this woman, just as I would like to have comforted my mother. But there are rules.

While I am reflecting on this, the door to the coffee shop opens and a student walks in, followed by the dog trailing its leash. A sign on the door insists that people not bring pets inside. One might argue that the dog was not brought in but entered of its own accord. In any event, the solution seems simple: I will take the dog by its leash and return it to its owner. Then I will finish my pecan roll on the bench and perhaps even offer some comfort to the woman. But she has disappeared. Has she gone looking for the dog?

I sit down on the bench, with the dog at my feet. After 20 minutes, and no sign of the woman, I look at the tag on the dog’s collar. Her name is Molly, and there is a phone number to call if you find her. I dial it only to find that the number has been disconnected. Molly, it now seems clear, has been abandoned. Growing up, I never had a dog. When we lived in the big house with the garden, my mother said that my baby sister was too small to have a dog around. Later, when we moved into a building, she said our apartment was too small. But finally, it seems, I will have a dog. I can’t just leave her here, so I decide to take her home. On the way, we pass a pet shop called Paws, a name I find nauseating. Why not Claws? We go inside to find something for Molly to eat. I have no idea what kind of dog she is, to say nothing of her age. She’s too sedentary to be a puppy. The man in the store suggests dry bits. The ingredient list is mindboggling, including chicken meal and brewer’s rice, and additives like alpha-tocopherol acetate and inositol, sounding like something a doctor might prescribe. I buy a large bag of it for Molly, as well as a water bowl, a rubber bone for her to play with, and a few treats in case she would like a snack. At my apartment building, the doorman asks if I have bought a dog. I explain that I am only taking care of one for a few days. Molly does not show much curiosity about my apartment. She finds a comfortable spot on the rug and falls asleep.

I have no idea what time Molly is accustomed to eating. The man in the store said twice a day is about right. I assume she has had breakfast, so I decide to wait until evening. In the meantime, there is a dog park nearby that I always avoid, but maybe Molly will like it. When we get there, though, she shows no interest and just lies down and goes to sleep. After a while, I call her name, and she gets up and walks home with me. Later, when I put some bits in her bowl, she takes a few perfunctory bites and goes to sleep again. I guess she has had a hard day.

A week passes, during which Molly and I establish a daily routine that revolves around going for walks. But she still prefers sleep to playing with other dogs and doesn’t eat much. I try feeding her different things, but she keeps getting thinner. Sometimes she comes over to where I am working and looks up at me as if to tell me something. I wish that I knew what. Maybe she is not feeling well. Some friends of mine know a veterinarian, so I make an appointment. Dr. Snyder puts Molly on a table where he can look her over. Then he takes some blood. Molly does not protest. I wonder if she has done this before. Dr. Snyder says he will call in a few days.

I hardly ever cry, not even when my mother died. But when Dr. Snyder calls, I cry. I dissolve in tears. Molly is not going to live very long. I will keep her with me until I have to let her go. I now understand why the woman outside the coffee shop was crying. She knew.

Chapter 2

I have a flypaper memory for jokes. I even remember some from when I was a kid. What has four wheels and flies? A garbage truck. Or there’s the one where I’d call a neighbor and say I was from the electric company. “Is your streetlight on?” “Yes.” “Well, don’t forget to turn it off before you go to bed.” That kind of thing. Now I sometimes think of a topic at random and try to find a joke that goes with it. Fish. A man steals a fish from a fishmonger and hides it in his coat, but the tail is sticking out. The fishmonger says, “Next time steal a shorter fish or buy a longer coat.” Sometimes I make up jokes. What does an Indian say to a mermaid? “How?” Some things are beyond jokes. Like Molly’s death. She got so sick that I had to take her to the vet to be put down. That’s the phrase they use—“Put down.” Do they put people down, too?

I saw a psychiatrist for a while. I had just broken up with a woman who said I should have my head examined. Dr. Levman’s office was in his house, which had two sets of stairs—one leading up to his office, the other down to the exit—so patients would never meet. He asked why I was there. I said I wasn’t sure. He asked who I talked to about my problems. I said I talked to friends. He suggested that talking to him would probably not be less useful than talking to them. I asked if he was a Freudian, to which he said only that Freud was a “very quotable fellow.” I felt we would get on. At our sessions, we always sat facing each other. He generally kept his eyes closed and looked like a very observant, deceptively sleepy cat—whiskers and all. When I came for a visit, he always asked what I had been thinking and feeling. I could never think of anything to say at first, but by the end I would be in tears. I was grateful for the separate staircase. Dr. Levman died some years ago; otherwise I would talk to him about Molly.

Once we discussed marriage. Put more accurately, he wanted to know why I was not married. I told him that when I thought of marriage, I pictured a large cage in which I was trapped but got fed three times a day.

“That doesn’t leave much room for sex,” he said. “If you want a Jewish girl to stop having sex, just marry her,” I responded. “What is your idea of the ideal woman?” “We have great sex until midnight and then she turns into a pizza.” “Do you really mean that?” “Not really, I don’t much like pizza.”

The woman who had dumped me cited what had become a familiar complaint— my lack of commitment. She once said to me, “You are the only man I ever loved and you won’t marry me.” At the time she said this, she was legally separated from her first husband. “Didn’t you love him?” I asked. She wanted a child, she said. There were times when we walked by stores for baby things and she would insist that we stop and look in the window. She said I should give up my apartment and move in with her. I was never going to give up my apartment. It was my escape hatch. I explained this to Dr. Levman, who asked why I needed an escape hatch. “To keep from drowning,” I said. I guess she was right to dump me. She got married two more times but never had a child. I wonder if Molly ever had puppies.

I told Dr. Levman a psychiatrist joke. He pretended he had not heard it before. A man goes to see a psychiatrist and says, “Doctor, I feel inferior.” The psychiatrist responds, “Your problem is that you are inferior.” I don’t feel inferior, but I don’t feel superior, either. I am of average height and a little overweight, and my hair is turning gray. But I do have a very good memory. I remember things that people—especially women—said to me years and years ago. I can play them in my head like a CD.

Here is a thought. Imagine that Isaac Newton comes back to life and starts to wander around New York City. What would surprise him most? There is the obvious—the cars, the lights, and that sort of thing. But I think he would have the most difficulty understanding all the people talking into small black rectangles. In his day there would have been the odd nut talking into thin air, but this? It has eroded our sense of privacy. People talk on their cell phones about almost anything, and it seems to have slopped over into general discourse.

The other morning in the coffee shop, two women were sitting right next to me and talking loudly to each other about menopause. They described their periods and their hot flashes. They must have known that I was listening. I could not help but listen. I was tempted to join the conversation. None of the women I have known liked their bodies. I wonder if any women do. I like their bodies, but that does not count. I once said to a woman, “It seems very hard to be a woman.” “Not if you are good at it,” she answered, “and I am.” It is a lot easier to be a dog.

Chapter 3

My friend Anne recently told me, “I do not know what a barge pole is, but I wouldn’t touch you with one. You are the Typhoid Mary of relationships. Only you would find a female dog who would die on you in two weeks and break your heart.”

I explained that I did not find Molly, she found me. “That’s what you said about that model who used to call you at two in the morning and ask if Germany was the country that had an East and West Germany.” “She had an interest in geography,” I said. “What ever happened to her?” “The last time I heard from her, it was a letter from a mental hospital that began,

‘I no longer hear voices.’ ” “What did you see in her?” Anne asked. “She had a body like a Greek statue.” “You men, it is amazing you can get anything done. You keep stumbling over your libidos.”

To change the subject I told her a story I’d heard about General de Gaulle. An admirer once gave him a turtle. De Gaulle asked how long it would live. About 150 years, the admirer told him. “Just when you learn to love them, they die,” de Gaulle said. I wonder how old Molly was when she died.

I used to go to a Pilates studio on Eighth Avenue run by Joseph Pilates himself. It had a strict dress code that required ballet slippers and plain T-shirts. (One day, I wore one that read, “Good girls go to heaven. Bad girls go everywhere.” I was told to change it.) Pilates was short but built like a fireplug. He had a German accent and a glass eye, which he would fix on you and say, “Vee train your mind.” The changing room was primitive. Men and women were separated by a barrier of loosely joined lockers through which the men could catch a glimpse of the women in various stages of undress. I suppose they might also have caught glimpses of us. I imagined looking through one of the gaps and seeing an eye peering back at me from the other side. It never happened. But you could listen to the women’s conversations, a never-ending source of amazement that might go something like this:

Woman 1: That is a lovely ring.

Woman 2: My fiancé gave it to me.

Woman 1: How long have you been engaged?

Woman 2: About three years. He is becoming a dentist.

Woman 1: Are you living together?

Woman 2: No. He is living with his mother.

You could write a whole novel about this doomed couple. The men on the other side of the partition merely grunted at one another. I asked Anne about this. “Women know what matters,” she explained.

Chapter 4

Have you noticed this change in discourse? If you thank a clerk in a grocery store, often the response is, “No problem.” Why should it be a problem? I imagine leaving an orgy and the hostess saying, “Thank you for coming,” to which I respond, “No problem. May I come again?” The 1960s, at least in New York, was a kind of orgy. I refer to this period as the PPPA era—post-Pill, pre-AIDS. Most diseases you could pick up were curable. Some of the women I slept with never even told me their names. I have a vivid memory of November 9, 1965. I had been invited to a party and had gone into my bathroom to use the electric razor. The light over the basin did not go on, even after I changed the bulb. The whole city was dark. The phone still worked, so I called my friend to ask if the party was still on. “Absolutely,” he said. I walked several blocks to his place and found it candlelit and full of people. I began talking to a girl, and when it was time to leave she came with me. No one wanted to be alone. It was a warm fall night with a full moon. We held hands for reassurance. When we got to my building, we had to walk up 18 flights of stairs. People were coming up and down with flashlights. I told her that they reminded me of Diogenes, who had wandered ancient Greece with a lantern searching for an honest man. We spent the night together, and the next morning I walked her down the stairs and never saw her again.

Diogenes was a “cynic”—derived from the Greek word kynikos, meaning doglike. Dogs are “shameless” and go about in a state of nature. So did Diogenes. Dogs can distinguish between friends and enemies instinctively. I am quite sure that Molly thought of me as a friend. Maybe I should have let her die in my arms, but she was so sick. And Wittgenstein—what was he on about? Teach a dog to howl even when it is not in pain? Why?

Wittgenstein and Hitler were born in Austria, just six days apart, in 1889. Both attended the Realschule, or technical high school, in Linz at the same time but were in different classes—Hitler had been held back a year; Wittgenstein had been moved up by one. Had they met, they would have disliked each other intensely. Hitler spoke German with a Bavarian accent, while Wittgenstein spoke an especially pure form of High German with a stutter. What a pair they would have made! Wittgenstein was baptized a Catholic but because of his family history was considered a Jew under the Nazi race laws imposed by his old schoolmate. (He paid to have his family reclassified as “Aryan.”) If only he had taken Hitler home with him to one of the Wittgenstein mansions—his family was one of the richest in Europe—might history have changed? “Adolf, I would like you to mmeet my ffather KKarl and my ssister MMMargaret …” Suppose Hitler had married Margaret, once painted by Gustav Klimt. The lives that might have been spared. As it is, Hitler was kicked out of the Realschule for bad grades. Wittgenstein was a decent student except for spelling. He simply could not spell.

Hitler played the piano, and Wittgenstein took up the clarinet in his 30s. If only Hitler had been invited to the Wittgensteins’, he could have met composer Gustav Mahler or conductor Bruno Walter, both of whom frequently gave concerts there. He might have gotten to know Wittgenstein’s brother Paul, a concert pianist. Having lost his right arm in World War I, he commissioned Maurice Ravel to write his Piano Concerto for the Left Hand. Talk about making do with adversity. Wittgenstein and Hitler fought on the same side in that war, during which Wittgenstein was captured and sent to an Italian prison camp. Three of his brothers committed suicide. I have not been able to learn if the family kept dogs.

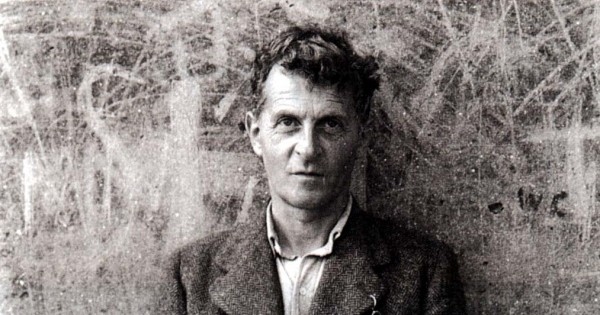

Anne showed up to the coffee shop one morning wearing an eggshell-blue, long- sleeved T-shirt emblazoned with a photograph of Wittgenstein. He was staring out at me with those coal-black raven eyes. I asked her why she was wearing it.

She said, “I know you have a thing about Wittgenstein, and besides, he was quite good looking.”

“His sexuality was a bit mixed up,” I said. “He was both AC and DC. He once traveled to Iceland with a Cambridge undergraduate in mathematics. He bought clothes for the young man and paid for his first-class ticket. In 1913, when his father died, Wittgenstein became one of the richest men in Europe. Later, he proposed to a Swiss woman on the condition they never have children. She left town.”

Nineteen-eighteen was quite a year for Wittgenstein. He had completed his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, the book that made his reputation. He had worked on it while a prisoner of war in Italy. Meanwhile, his uncle died, his brother Kurt committed suicide, and the young man with whom he’d gone to Iceland was killed in a plane crash. Wittgenstein dedicated the Tractatus to him, gave his money away to his siblings, and became an elementary school teacher. Before the war, he had gotten to know Bertrand Russell at Cambridge, and in 1922, when the Tractatus was finally translated into English—the original German appears on opposing pages—Russell wrote the introduction. The book is a series of numbered propositions. For example, Proposition 5.6 reads, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

This is not exactly something out of which you can build a code of conduct. It sounds more like a teenage statement of possession. Anne asks me if she should try to read it. “You would have to have a high tolerance for statements like “not (not vanilla and not chocolate) means the same thing as vanilla or chocolate.” “Why?” she asks. I am not sure what she is referring to, but whatever it is, I do not have a good answer for her.

Chapter 5

At first, Wittgenstein used an assumed name when applying for teaching jobs. Had potential employers known he was a Wittgenstein, their suspicions would have been raised. Perhaps they’d have thought he was crazy or some kind of pervert. He must have had a good deal of time on his hands because he read The Brothers Karamazov several times. I wonder if he was able to keep the names straight. The novel’s hero, Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov, appears in the book as Alyosha, Alyoshka, Alyoshenka, Alyoshecka, Alexeichik, Lyosha, and Lyoshenka. It sounds like the declension of an irregular Latin verb—fero, ferre, tuli, latus. Maybe he identified with one of the characters—possibly Alyosha, who was also having problems with his brothers. Wittgenstein was certainly not into murdering his father for an inheritance, seeing as he gave his away as soon as he could.

Wittgenstein raised the question of whether a dog could be trained to be insincere. Could it be taught to cry out in pain even when it wasn’t feeling any? One would somehow have to get across to the dog the reason for doing this, maybe with a treat or a pat on the head. I think of this when I pass the pet store where I bought food for Molly. Behind its big picture window there are always two or three puppies cavorting on what looks like a bed of confetti. I suppose they pass their nights in a kennel inside the shop. They must have an odd view of the cosmos. Why, they might wonder, do we spend so much time in this window? They have no idea that, should someone buy them, their lives would take a quantum leap. With enough luck, a nice family might even take them to the beach. If one could make the puppies aware of this, might they try to behave in ways more appealing to buyers? Might one of them come to the window and extend a paw? As it is, they simply romp around. I think Molly was sincere. What you saw was what you got. At the end she could not give much, though she tried.

Chapter 6

Anne is trying to read the Tractatus. She is having a difficult time understanding it and seems annoyed with me, as if it were my fault. I ask if she has read Wittgenstein’s preface, in which he suggests that only people who have had similar thoughts will understand the book.

“What a stupid idea,” she says. “If I had had similar thoughts, what would I need him for?”

“Isn’t that what friends are for?” I asked. “With a friend like Wittgenstein …”

To cheer her up, I mention some things in the Tractatus that seem flat-out wrong. Take what Wittgenstein says about hieroglyphics: “In order to understand the essence of the proposition, consider hieroglyphic writing, which pictures the facts it describes.”

The problem is that this is not what hieroglyphic writing does. Take the example of ducks. The symbol that looks like a duck but has a vertical line stands for a duck; the one without a vertical line stands for a syllable.

The Egyptians, in other words, had a syllabic alphabet. If you think about it, it had to be so. How else would you be able to refer to an individual without drawing his picture?

“Why did Wittgenstein get into this, especially if he did not know what he was talking about?” Anne asks.

“He had a pictorial view of propositions,” I reply. “Take Proposition 4.06, which reads, ‘Propositions can be true or false only by being pictures of reality.’ ” “But what about his propositions about language? They were in the language he was trying to picture.” I had to admit that this was a logical cleft stick. In his introduction to the English translation of the Tractatus, Russell suggested that Wittgenstein’s propositions needed to be couched in a metalanguage. Even so, wouldn’t propositions about this metalanguage have to be expressed in an even higher metalanguage? You quickly get stuck in an infinite regress. Wittgenstein understood this and, at the end of the Tractatus, expressed doubt about the whole enterprise, writing that people who truly understand him realize that his propositions are senseless. That last one, 6.34, reads, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” “That is just like a man,” Anne notes. “He writes a whole book about something that he says he cannot write about. No woman would do such a stupid thing.”

Chapter 7

Wittgenstein once asked a friend why people used to believe the sun revolved around the earth. “Because it looked that way,” said the friend. Wittgenstein then asked, “How would it have looked if it had been the other way around?” Wittgenstein was deeply concerned with a curious aspect of language: you can form a sentence in which every word has a meaning, but the sentence itself might still be meaningless. Not only is the whole less than the sum of its parts, the whole is zero. He gave as an example, “Socrates was identical.” He felt that much of academic philosophy consisted of arguments over propositions like this—and as it happened, a group of scientist-philosophers in Vienna agreed with him. It had begun before World War I as a collection of friends who met in Viennese coffeehouses to discuss how to rid modern science of metaphysics. Their discussions were aided by Linzer Torte and Kaffe mit Schlag. The group disbanded when the war broke out, only to be reconstituted later under more formal circumstances at the University of Vienna. It became known as the Wiener Kreis, or the Vienna Circle, and its members undertook to write a short scientific encyclopedia. When the Tractatus was published, they decided they had to understand it and went over it line by line. At the time, Wittgenstein was living in Vienna, where he had been working as an architect and a gardener. They invited him to join the circle. He attended some meetings, where he sat quietly reading poetry, occasionally emitting some seerlike utterance. But soon he stopped going. Science was never Wittgenstein’s strong suit. The references to it in the Tractatus have to do with Newton and Darwin. He apparently had no interest in Einstein.

In 1929, Wittgenstein returned to England to teach at Cambridge. English economist John Maynard Keynes met him at the station and later wrote to his wife, “Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5:15 train.” But there was a problem. Wittgenstein had no academic degree, so he was told to submit the Tractatus as a Ph.D. thesis. As he turned it in to his examiners, Bertrand Russell and moral philosopher G. E. Moore, he told them they’d never understand it. In his report, Moore wrote, “I myself consider that this is a work of genius, but even if I am completely mistaken, and it is nothing of the sort, it is well above the standard required for the Ph.D. degree.” In 1939, when Moore retired from Cambridge, Wittgenstein succeeded him as a professor of philosophy. He gave what he called lectures, but they were more like disjointed utterances. One of the students noted that “his face was lean and brown, his profile was aquiline and strikingly beautiful, his head was covered with a curly mass of brown hair, but I observed the respectful attention that everyone in the room paid to him.”

Wittgenstein took up residence at Trinity College, where he happened to live in the same building as a friend of mine. Because of food rationing, residents prepared their own dinners, and my friend remembers the smell of fish wafting from Wittgenstein’s apartment. Day after day, they passed each other on the stairwell and said nothing. Then one day Wittgenstein invited my friend over for coffee. My friend sat down in the only chair—a sort of deck chair—while Wittgenstein stood by in silence. My friend had read the Tractatus when he was a teenager and decided he should say something. He asked Wittgenstein if he had changed his mind about anything he had written in the Tractatus, to which Wittgenstein replied, “Tell me, which newspaper do you represent?” The conversation ended.

Chapter 8

The Tractatus has brought Anne and me closer. We struggle over propositions like “That which expresses itself in language, we cannot express by language.” I wonder if the proposition “That which does not express itself in language, we can express by language” could be equally valid. We need guidance. Sometimes Anne tells me that I should get another dog. Maybe I will, but it is too soon. I am still grieving for Molly. But last night I had a dream about Wittgenstein. He had gone to see Dr. Levman.

“Why are you here?” asks Dr. Levman.

“What do you mean by ‘why’?” replies Wittgenstein.

“You do not seem very friendly,” says Dr. Levman. “Remember what you wrote: ‘A friendly mouth, friendly eyes, the wagging of a dog’s tail are primary symbols of friendliness; they are parts of the phenomenon that are called friendliness.’ You do not seem to have friendly eyes.”

Wittgenstein is surprised by this. He is not used to dialogue with students. He is also annoyed by a reference to dogs. “You need a dog,” Dr. Levman says. Before Wittgenstein can respond, I wake up. I have decided to go with Anne to the pet store and look at dogs.