A Visit to Epidaurus

When a play ends with a dismemberment, the effect on the audience can be transformative

Last summer, I flew to Greece to see a production of The Bacchae at the Epidaurus Festival, two hours south of Athens, in the Peloponnese. I wanted to see what Euripides, the last of the three great playwrights of ancient Greece, could teach me about theater. Which might seem like a lofty ambition. But I also just wanted to get away.

Of the 92 plays that Euripides wrote, The Bacchae is one of 19 to have survived. He composed it just before his death in 406 BC. It is one of the few Greek tragedies in which Dionysus, the god of theater, is a character. It is also one of the few that ends with sparagmos, the Greek word for the dismembering of a body onstage.

The Bacchae takes place in Thebes, far from the home of the eponymous Bacchantes, the group of Asian women who follow Dionysus’s cult, drinking and participating in orgies. Among them is Agave, the mother of Pentheus—the Theban king who is at once disgusted by and fascinated with Dionysus and his Bacchantes. Pentheus imprisons Dionysus. But the god escapes and burns down (or appears to burn down) Pentheus’s palace.

After that, the play changes tone. Pentheus pleads with Dionysus to let him spy on the Bacchantes. Eventually the god agrees, dressing the king in women’s clothes so the Bacchantes won’t recognize him. But they do, and in a frenzy, they rip him limb from limb.

Sparagmos is a transformation. For ancient audiences, this act of sacrificial violence was meant to elicit catharsis. It was appropriate, then, that I was going to see this play. Like the Greek theatergoer of the fifth century BC, I wanted to be transformed.

When I went to Greece, my father had had Parkinson’s for many years. I’m a little vague on the exact date of diagnosis. But what I am certain of is that Parkinson’s is a horrible disease, robbing human beings of body and voice. It is managed by increasing doses of L-Dopa and carbidopa, which elevate dopamine. One side effect of the drugs is dyskinesia, a Greek word that means difficulty in moving. Your limbs twitch. Your tremors increase. In an effort to control certain aspects of your body, you end up losing control of others. Another side effect is hostility. But that’s less of a surprise. People tend to get hostile when they’re dying. Why shouldn’t they? A third symptom is hallucination, although I’m not sure whether that’s caused by the drugs or the disease. In any case, my father had nightmares and lost inhibition, and he said things he never would have said before.

Parkinson’s transforms your body and your mind. You become something other than the person formerly known as yourself: an actor playing a new role. You could say that your body becomes a form of theater—theater that you didn’t choose to participate in.

In the first years after the diagnosis, it made me angry that my father, who had been a doctor, forwent therapies such as deep brain surgery that other Parkinson’s patients I knew said were helpful. But then, I had to admit that this choice was in character. He had always exhibited what, in my meaner moments, I thought of as a special brand of resignation. Or maybe it wasn’t resignation at all. This was the person who made my brother and me pick up trash along the same road where he foraged for wild grape leaves to make his homemade dolmas. He would try to fix the world and inculcate that ideal in his children, but after his diagnosis, he knew he had only so much time. Why was it surprising that he didn’t want to spend the time he had left in the OR?

Later, I begin to wonder if it was stoicism that made him reject therapies. At any rate, I stopped being angry about his acceptance of the course of the disease. I saw that he was right in not wasting energy fighting something he couldn’t defeat.

Over the years, his body fell apart. At least once, my mother called to say that my father had fallen and was lying on the floor and that they were waiting for the paramedics to take him to the ER. He lost his voice. “Speak louder,” my mother would yell when she put him on the phone. He could manage a word or two at normal volume and then would trail off. According to my mother, he could still understand what we said.

My father died some months after I returned from Greece. He was in New Jersey. I was in Chicago, some 800 miles away. There was nothing cathartic about his passing, no violence to break the numbness. His death was, for me, disembodied.

Epidaurus, which dates from the fourth century BC, is in a sanctuary devoted to the god of medicine. The theater seats 14,000. In ancient times, seeing plays there was thought to be therapeutic for the sick. Today, a winding path leads uphill from the parking lot, past cypress and pine trees, outdoor concessions, and gift stores. You enter the theater through the parados—the side door, made of huge white limestone slabs tucked into a hillside.

I have always loved The Bacchae’s mix of savagery and modern gender-bending elements. Savagery drives the plot. In his program note to this production, the director, Thanos Papakonstantinou asks, “Is violence the only language we understand?” Pentheus’s dismembered body, he writes, gives audiences the opportunity to think about whether anything can really be put back together again once violence has riven it. Reading

Papakonstantinou’s note, I imagine my father’s memorial service to come. I think about how I will have to pick up fragments of his life that I would rather forget—a remembering after the dismembering. Things he said and did, removed from context. Could such fragments conjure up a person?

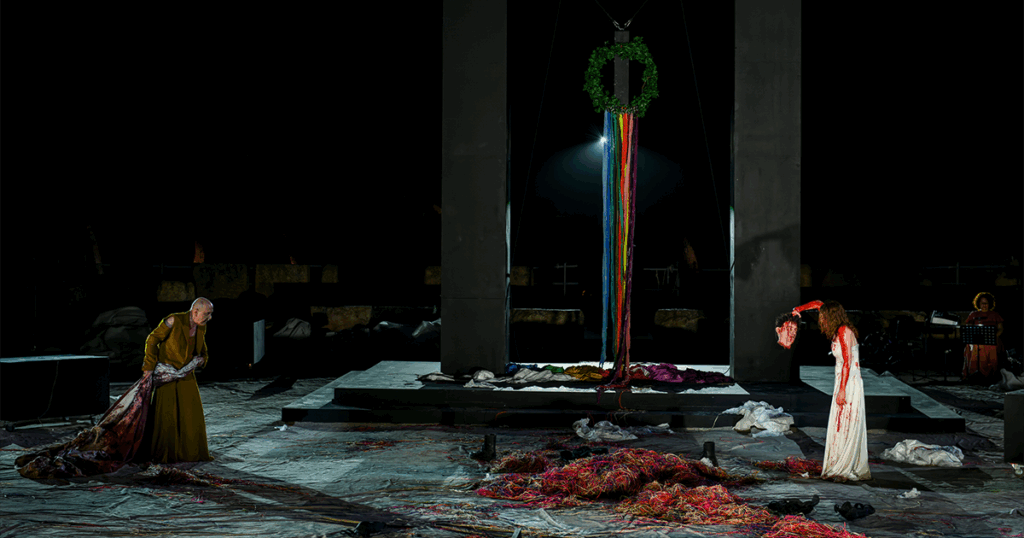

The play starts, jolting me to the present, to the hot, dry summer air and the spectacle unfolding onstage. The bearded, bare-chested Dionysus speaks the first line: “I am here.” This Dionysus clowns around. He claps, and the lights snap on and off, illuminating the trees around the theater. He dips his hands into a large box that holds cans of red and blue paint. Before long, paint of all colors drips from his face and body. At first, all of this is funny, but soon, it becomes less so. The Bacchantes run onto the stage, singing and dancing, shrouded from head to toe in sheer, luridly tinted veils. When they whirl them off, they’re wearing tiny bikinis spattered with paint that looks like blood. They kick around sacks stuffed with rags that are meant to represent pieces of human bodies.

The Bacchae captures the dual nature of theater, which simultaneously asks you to see actor and character, truth and fiction. Pentheus and Dionysus are king and god, but they are also two actors playing roles, espousing different sets of ideas, serving as mouthpieces for their ancestors. Dionysus takes on the part of director, casting Pentheus as a Bacchante, outfitting him in a wig and a dress so that the real Bacchantes won’t recognize him. He makes Pentheus fly to a treetop, ostensibly so that the young Theban king can watch their orgy undetected, but Dionysus is really orchestrating his revenge for having been imprisoned.

As I watch The Bacchae, time hangs. I am impatient for the ending, which feels like it is never going to come. I know the fate awaiting Pentheus, and it is almost too terrible to bear. Ultimately, a messenger narrates Pentheus’s gruesome end, how the Bacchantes, led by Agave, uproot the tree he is clinging to and tear his arms and legs from his body, even as he screams to his mother, “I am Pentheus, your own son.” The Bacchantes, now topless, gleefully cavort around blood-spattered strips of paper meant to be Pentheus’s innards.

Then Pentheus’s grandfather Cadmus, who has gathered the pieces of the dead king’s body from the forest, drags them onstage. Nothing of these remains resembles a person. There is no face to see or hand to hold. Maybe it is a lighting effect, but the creases in the rags give the impression of offal. When Agave enters, holding Pentheus’s head on a stick, she is still in a trance. She thinks the headless remains in Cadmus’s arms are those of a lion she has killed. It takes roughly 70 lines for Cadmus to convince his daughter that the lion is her son. Finally, he makes her look up at the stars. When she looks back down, the trance is broken. She sees what she has done.

The best theater arrives at such moments, when the audience sees what the characters cannot. There is a lacuna in The Bacchae, but the gist is that Agave has to go into exile. The last image is of Pentheus’s dead body onstage.

I don’t know what others in the audience feel, if they experience any communal suffering and catharsis. But when I see Agave crouching over Pentheus’s body, I think that there could be nothing crueler than this moment. The gods had made her kill her own child so savagely that she couldn’t even recognize his remains.

For as long as my father had been ill, my mother repeated the same sentence: I thought he would get better. In the play about her life, she is her own chorus. Her monologues, delivered as we sat in the parking lot of a strip mall near my parents’ assisted living facility, rattle around in my mind. Their story is not like the one in The Bacchae. But like Agave, my mother seemed to be in a trance. It’s her surprise—at her own misfortune, at my father’s decline and death—that tears me up. Is this what the ancients felt when they experienced death, which, back then, was much more visible? Were the ancients any more ready for the death of a loved one than we are, all these centuries later?