After my mother died, I taught my father how to hear her voice and feel her presence. I did not have a strong conviction that she really was present, despite the way her eyes had looked up as she slipped away, as if she could—as the hospice nurse put it—see the dead waiting to receive her. A shocking silence descends the day after someone has died at home, as my mother did. Before the death, there are caregivers, shifts of bustling people you know but do not know, who help the ill person eat and bathe and use the toilet. There are people everywhere, always in and out, people cooking and caring and relatives just waiting. And then, suddenly, there is only silence, with piles of unused pills in orange bottles and no one in the kitchen anymore.

My irreligious father had none of the scaffolding that most faiths provide for loss. I am an anthropologist who studies the way people relate to invisible others, and because of my work, I know how people learn to feel the dead. I thought that might help. I told him that in the months after a loss, most people hear or see or feel their dead loved ones. I told him that if he talked to her as if she were there, he would be more likely to feel her respond.

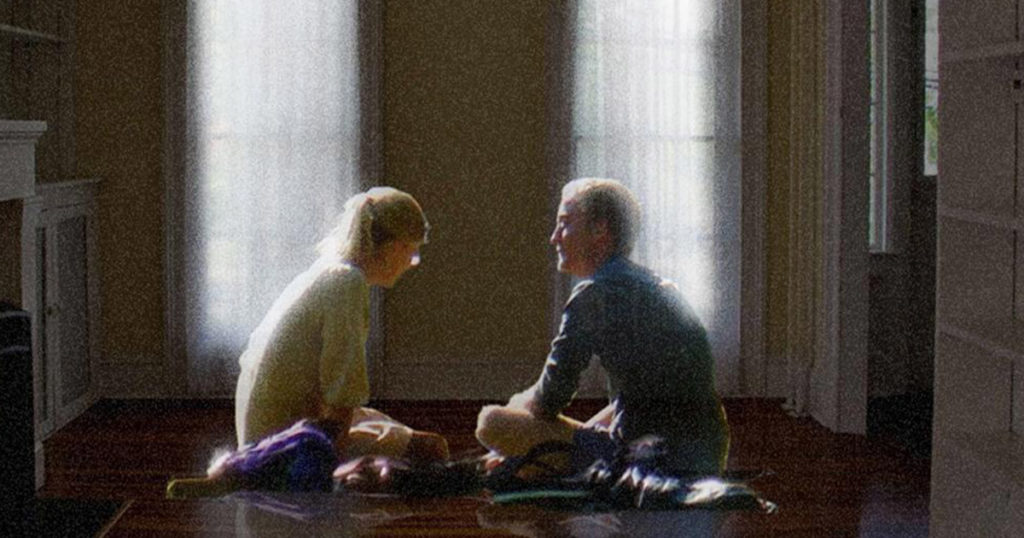

We returned the ugly hospital bed that we had set up in her downstairs study. We brought back in the plants that she loved and dusted off her books. I found the doll she’d had as a child and placed it on a shelf next to some of her artwork. We made a nice place in the study for my father to sit. He began to go in every day. In the morning, he’d put in his head to say hello—he’d say this out loud—and he’d say goodnight before bed. Usually, he’d spend an hour in there after dinner, just sitting and thinking about their life together. He called that meditating.

I told my father that when people join churches where they expect to hear from God, they learn to listen for God, to pick out thoughts in their minds that they think could be his responses, somehow placed in their minds by the divine spirit. They are told to focus on the thoughts that feel louder, stronger, more surprising. Pastors tell these new congregants to closely examine these thoughts and to ask whether they are the kinds of things God would say. The pastors warn people that they can get it wrong, that they can think that God has spoken, but really, it was just their own thoughts after all. I told my father that despite these doubts and questions, most new congregants begin to feel that God is talking to them anyway.

My father started to sense my mother in the house. She was more present in her bedroom and in the kitchen, and when my father was doing something he knew he shouldn’t, like making a mess on the kitchen table. Sometimes he’d be at his desk and feel her standing behind him, the way you know that someone is behind you even though you don’t turn to look. His awareness of her had a visual quality, although it wasn’t a hallucination. It was more that he really felt she was there, as if he knew with his senses even though his senses knew nothing. He said it was like going out at night to shut up the chickens and knowing that there were coyotes lurking in the fields—even though he could not see them, they were there in the darkness, and they terrified him.

And then my father began to hear my mother speak. He was always skittish about talking to me about these moments. He’d call to tell me about them and then refuse to tell me what she said. I think they felt too intimate, too raw, too weird. Still, he told me she’d spoken to him maybe five or six times. Her voice felt like it came from his tummy. It felt audible, even though he knew it wasn’t audible. He began to use the pronoun “we” when he talked about the house and the dogs. Sometimes he’d catch himself and revert to “I.” He knew perfectly well that his wife was dead. Yet in some way, he had come to feel that she was there.