Nadar—the pseudonym of the most famous photographer in 19th-century France, Gaspard-Félix Tournachon—was a celebrity, renowned not only for his portraits of eminent contemporaries but also for his caricatures, his writings, his radical politics. The person Félix photographed most frequently was himself—out of curiosity more than vanity. He experimented on himself, attempting to push portraiture as far as it would go in its fundamental mission of revealing identity. In other words, he tried, fitfully, to set aside his habitual showmanship and show who he was. He worked at a disadvantage: there was no one to charm him out of his self-consciousness. His usual trick was to banter with the sitter, but he couldn’t be expected to banter with himself. Also, he was notoriously bad at holding still: the real Félix was in constant motion, frenetic energy a defining element of his personality. Was he the same man when frozen in place? If Nadar asked a friend to sit for him, he would manipulate the pose and the lighting, chatting away all the while, then step back and examine the result. When he sat for himself, with an assistant releasing the shutter, he could gauge the effectiveness of the pose only after the print was developed. And ironically his eyesight was poor: behind the camera he wore his spectacles, but in front of it he removed them. (You sometimes see them in portraits dangling from a ribbon around his neck.) Sitting for a self-portrait, he was in a sense doubly blind to the goings-on.

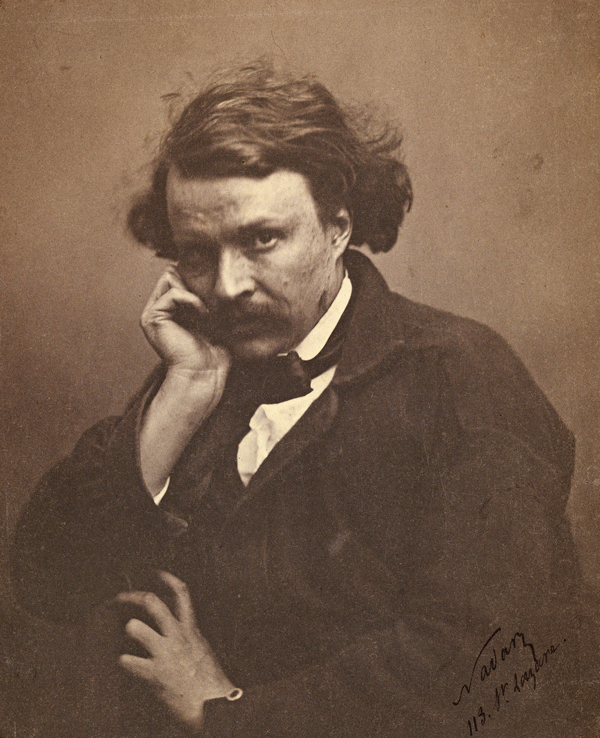

Often what we get is only a glimpse of a certain aspect of his personality. The very earliest self-portraits mostly show eagerness. Still unsure of his technique, he wanted the image to prove at least recognizable: apprehension mixes with impatience and desire to produce nothing more than a fuzzy, pleading look on the face of a bohemian no longer in his first youth. As his confidence grew, his ambition asserted itself, and he achieved specific calculated effects. In a striking seated portrait, he looks directly at the camera and attempts—perhaps too transparently—to seduce the viewer with his charm.

He tilts his head forward and slightly to the side, rests his cheek on his hand, and fixes you with one hopeful eye. (The other is deep in shadow.) He appeals silently for an intimate exchange. Although his hair is uncombed, he’s more neatly dressed than usual, his black cravat crisp against the white of his shirt. If he’s aiming for sincerity, he has missed the mark; the result is more coy than genuine.

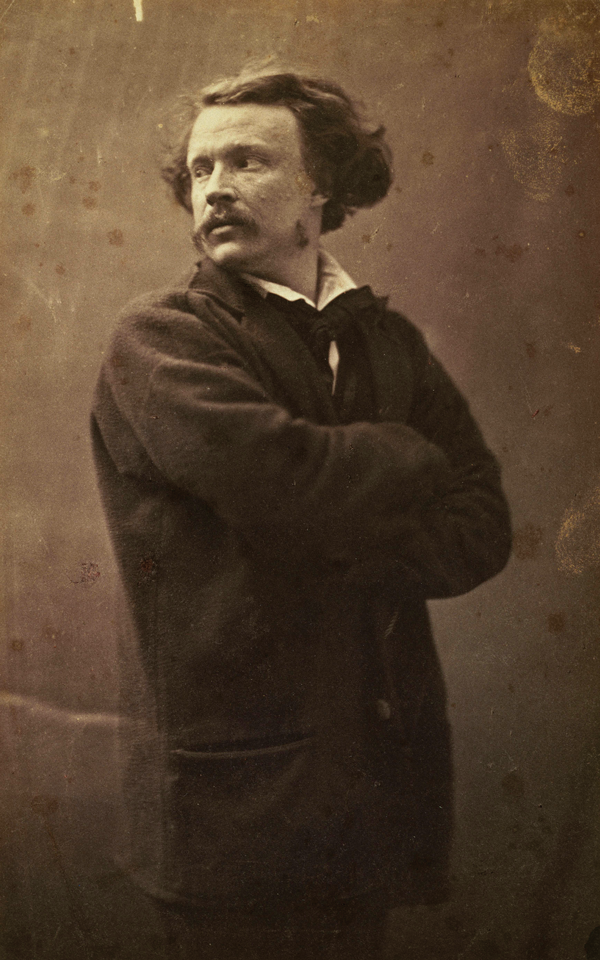

In another early self-portrait, he stands tall, his body at an angle to the camera, arms crossed and hands buried in the sleeves of his jacket, head swiveled so that he looks back over his shoulder.

It’s a theatrical pose with heroic overtones: behold Nadar as romantic artist, isolated, exposed, self-contained, self-protective, ready to move forward, but conscious of what’s behind him—which in this case might be the painterly tradition of portraiture. A hint of vulnerability, of anxiety in the eyes and around the mouth, adds considerably to the interest of the photograph. Was Félix truly anxious? Or is this a deliberate imitation of troubled genius?

The best photos of Félix aren’t formal self-portraits. A photo-montage of our hero dancing the cancan on the tiptop of a steeple (or is it the point of an ink pen?), an absurd image that caricatures Félix’s long legs and somehow catches his anarchic spirit: he’s wild-eyed, wild-haired, astonished, and worried about his precarious position. I don’t know who did the cut-and-paste job, splicing comically elongated limbs onto a Nadar self-portrait, or who inscribed it to whom (the inscription reads, “To the great man / the instant daguerreotype / with gratitude”), but my guess is that it was a present to Félix from a waggish friend.

The other revelatory portrait is an experiment in making moving pictures: a dozen photos of Félix from the chest up, taken from 12 successive angles—flip through them and you have a revolving portrait.

In the sixth photo, when he’s just about to face the camera straight on, he grins; in the next photo the sly smile is gone, replaced by a level stare.

The effect is like a playful wink or a wave, a subtle subversive signal to posterity. Hardly anybody smiled for the camera in the mid-19th century; to do so was to risk appearing foolish or simple-minded. Today’s ubiquitous smirk was unthinkable. Yet Félix, unwilling or unable to smother his high spirits, flashed his grin—and so left proof that the friends who celebrated his boisterous good humor understood him best. It’s the confirmation of Baudelaire’s remark: “Nadar, the most astonishing expression of vitality.”