A Writer by Nature

An excerpt from World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Acclaimed poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil endured a somewhat rootless childhood, moving from state to state, at times having a difficult time fitting in. Yet one thing remained constant through the years: her curiosity about the natural world. Her latest book, World of Wonders, is a collection of intensely lyrical essays exploring the myriad lessons that nature can teach us. One of those pieces, “Comb Jelly,” is excerpted below.

Who on earth would think to give solid glass bracelets to a four-year-old? My eyes were big as quarters when I opened the box of bangles sent by my Indian grandmother. She thought it was time. I loved them right away: the shock of color when I held my thin wrists up to the sunny window, the clink and chime when I ran, the deep-drenched reds, blues, violets—nothing else rang so bold or brilliant in a Chicago winter. Outside, drifts piled higher than a toddler in Moon Boots. My father shoveled snow off our roof for fear of a cave-in. But I had my bangles. I ran from room to room just to ring them. Be careful, be careful, my mother said. You’ll cut yourself if they break.

And when I finally grew tired, I’d lie on the floor of our living room and listen for the strange sounds of winter: the scream of icicles as they slid off the edge of the gutters, the vermiculite in the cool soil of a houseplant begging for a drink. I held the bangles up to the ceiling light so I could fracture a rainbow across the room—so much power in a tiny bracelet of glass—the first time such radiance sprang from this little girl’s hand.

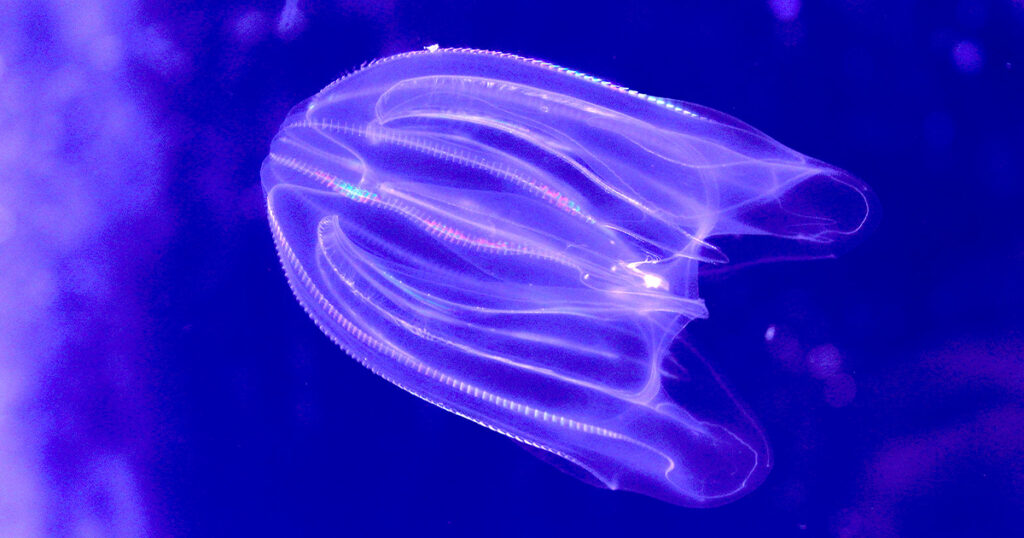

As an adult, I’m still so drawn to light-soaked color displays. Some of the planet’s most vibrant light shows come not from the land or air, but from the ocean. With the pulse and undulation of the comb jelly, hundreds of thousands of cilia flash mini-rainbows even in the darkest polar and tropical ocean zones. This zing of color is what tempts people all up and down the eastern coast of both Americas to gather walnut-sized comb jellies into their hands. But don’t do this! Most are so delicate (thinner than the thinnest contact lens) that they will disintegrate in your palm. If you want to observe one up close, scoop it into a clear cup and take a look-see that way. And then, of course, please gently return it to the water.

The comb jelly is a creature of delicacy. It doesn’t sting, and it’s not actually a jellyfish. It belongs to a whole other phylum, Ctenophora. Comb jellies can be as small as a single grain of rice or they can grow to over four feet in width—large enough (in theory) to gobble up a plump second grader whole. But they won’t, because they are too busy waving their hair-like cilia around, too busy eating various fish eggs, and too busy eating other comb jellies.

When I see them in aquariums, I think of the first time I held my glass bangles up to the light. I have always been drawn to color—the hue and cry of joy—and I think perhaps it was because someone on the other side of the planet entrusted those bangles, that fragility, to me when I was so young. What a waterworld comb jellies make, suspending their millions of rainbows not in the sky, but in the ocean—sometimes so far into the way-down deep and dazzle that only pale creatures like anglerfish and gulper eels take notice, perhaps imagining, for a brief moment, the delicious luxury of what it’s like to be warmed by the sun after a rain.