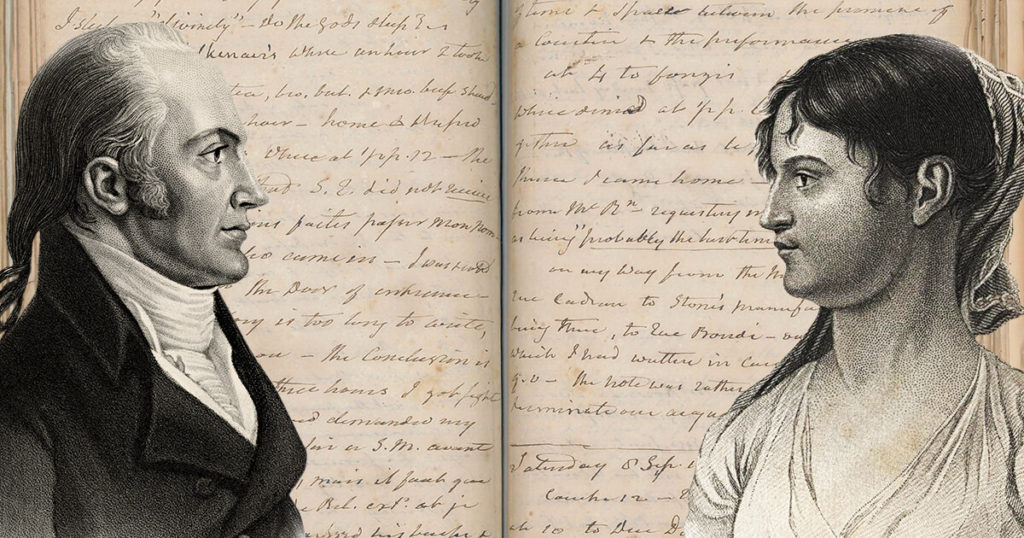

Aaron Burr in Exile

Surviving against all odds, his journal tells the story of one of the most maligned figures in American history

In June 1808, as he left North America for the one and only time in his life, Aaron Burr recorded the briefest of notes for his adored daughter, Theodosia. “Fair winds,” the founding father and former vice president wrote before clambering aboard a packet, the Clarissa Ann, in New York Harbor. Traveling under the assumed name of H. E. Edwards, Burr was headed across the Atlantic, the Furies at his heels. It wasn’t the first time he’d fled. In 1804, after killing Alexander Hamilton in their famous duel, he had escaped southward. This time he was facing even more severe consequences. Charged with treason after allegedly organizing a conspiracy to roust the Spaniards from their colonies in Mexico and the Southwest Territory, Burr was acquitted in September 1807, after a sensational trial in Richmond, Virginia. His enemies—and they were legion—were incensed by the verdict. Slanderous rumors about him continued to swirl. According to one, Burr was plotting to assassinate President Jefferson. An army of creditors was also in pursuit. Escape was the only option.

Burr would be on the run, and short of cash, for most of the next four years. Hounded by his enemies, he zigzagged across Great Britain, Scandinavia, and the European continent, living what he called “a spider’s life.” He traveled with a political goal, too, hoping to enlist European partners, up to and including Emperor Napoleon himself, in the liberation of the New World’s Spanish colonies. Desperate to return to his daughter, he was constantly thwarted, passing like Odysseus through a series of daunting challenges, one right after the next.

During this dramatic time of exile, Burr kept a diary that grew to fill five notebooks and a thousand pages, completing it just days after his return to the United States. He was done with his journal at that point, yet it seemed to take on a life of its own as it passed through the hands of subsequent generations. Today, it tells many tales, beyond the story of just one man.

From the beginning, Burr’s diary was more than a record of his time abroad. He conceived it as a conversation with “my Minerva,” one of the many endearments he had for Theodosia, who was living in South Carolina at the time, married to Joseph Alston, who would later become the state’s governor. “And again and again, I pray you to recollect that this is not a journal to read, but mere notes from which to talk or to speak, like a lawyer,” Burr wrote to her from Sweden. “It is my brief, from which I shall make you … many a speech.” The journal served as a protracted one-way conversation, one that Burr could step away from, then return to at will. His tone is playful and warm. In her correspondence, Theodosia matched her father for constancy: “You are always in my thoughts.”

Communication by mail in those days was scattershot. Burr’s political foes destroyed many of his letters, to and from; other correspondence failed to reach him as he darted from place to place. At one point, he was without news of Theodosia—then in chronic, agonizing pain after a difficult childbirth—for 15 long months. Forever at a distance, she must have seemed to him “like a breeze between his hands, a dream on wings,” in Virgil’s words.

Burr didn’t commune with Theodosia via the written word alone. He had a visual aid, too, one that seems downright comic in our era of digital photos on tiny phones. He toted a rolled-up portrait of her—an 1802 oil painting by his former protégé John Vanderlyn—in all manner of strange conveyances, from stagecoaches to a torture chamber of a vehicle known to its hapless riders as “the chamber pot.” The painting accompanied him through Holland, Scotland, Bavaria, and beyond. He would unfurl the canvas, contemplating her likeness as a kind of meditation. “I passed an hour looking at your picture,” he once wrote to her, touchingly. There were many such sessions. He even invited friends to join him in this adoration. One was the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham—a fan of Theodosia’s from afar—who sat side by side with Burr, the two gazing rapturously upon her image.

Theodosia’s mother was Theodosia Prevost, a widow whom Burr had married in 1782 and who died a dozen years later. Burr’s wife was a brilliant woman, a decade older than he; intellectual discourse was a binding thread between them. She was also a revelation. “It was the knowledge of your mind which first impressed me with a respect for that of your sex,” he wrote to her. He became convinced that women could be the intellectual equals of men—an opinion shared by almost no one in America at that time. Coming upon the writings of the English feminist and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, Burr was delighted to find that he wasn’t alone in this radical view.

From the outset, the younger Theodosia, born in 1783, was something of a social experiment. The couple had her tutored at home in the curriculum a boy would have received—reading, arithmetic, Latin, religion. Because Burr and his wife, whose stepfather and former in-laws were Swiss, often communicated in French, Theodosia learned that language, too. “I hope yet, by her, to convince the world what neither sex appear to believe, that women have souls!” he wrote. The warm, amusing, and heartfelt letters that passed between father and daughter for as long as they both lived testify to how well his experiment succeeded.

In his diary, Burr presents himself as a picaresque figure, an American rube, wandering across the Continent. In truth, he was anything but. A hero of the Revolution who’d attained the rank of colonel, he socialized with luminaries, from Goethe to Sir Walter Scott. In France, his local friends included Dominique Vivant Denon, the head of the Louvre, and the enigmatic Parisian socialite Madame Récamier. Burr was chummy with some of Napoleon’s inner circle, too, including the Duc de Bassano, then secretary of state. Wherever he found himself, Burr was an alert, socially conscious, at times wickedly funny observer. A dinner party in Frankfurt, for example, inspired him to quip: “You would think we were eating for wagers, such is the velocity with which the courses are served.”

All through his time abroad, he never stopped trying to move his complicated agenda for Latin America forward. In France, there was a protracted period in which Burr—desperate to bring Napoleon along with his own expansionist plans—received encouraging indications from his entourage, including the Duc de Cadore, France’s foreign minister. After the two met, Cadore assigned a young official to help Burr prepare a memorandum to be presented to Napoleon. After a few sputtering contacts, however, all communication between the parties ceased.

If Burr failed to gain the support of the French government, he had even less backing from some of his compatriots. A group of powerful American expatriates in Paris—including such Jefferson loyalists as John Armstrong, the U.S. minister (a post equivalent to ambassador)—soon entered into what Burr termed a “combination” against him. Burr’s passport was withheld, preventing his return to the United States. Ground down by poverty, he was in a “state of nullity,” he wrote to Bentham in 1809. Yet he remained preternaturally calm. As one commentator wrote a century later, “No matter how poverty stricken, how cold, or how hungry, he never complained, never denounced his enemies, never entered upon a justification, or even an explanation of remorse of his own conduct, and never lost his serenity of mind.”

Burr had a secret weapon—his diary. He wrote in it almost daily, usually in the evening, his feet propped toward a fireplace or a wood-burning stove, often with a “segar,” as he called it, in hand, a glass of wine or brandy at his side. The pressure on him could be crushing. Still, he recorded the minutiae of daily life—shoes taken for repair, the configuration of logs in a fireplace—as if clinging to a life preserver in a roiling sea. In 1809, for example, just days before being deported from Great Britain (he was facing trumped-up charges relating to an unpaid bookseller’s bill), he wrote of the events lightheartedly: “Mr. Jefferson, or the Spanish Juntas, or probably both, have had influence enough to drive me out of this country.” Then, in a lovely juxtaposition, he moved on to rejoice in a (temporary) triumph over insomnia. The big picture may have been appalling; still, in the words “I slept like an oyster,” he sounds exultant.

The first thing I noticed about Burr, when meeting him on the page, was the beauty of his handwriting. It’s gently slanting, easy to read. Which seems miraculous, given his difficult circumstances. The words spill out assuredly—and, at times, evasively. Spies were everywhere, particularly in Napoleonic France, where even the lamplighters on the streets were known to keep tabs on the citizenry. In his entries, Burr took pains to cover his tracks, shifting deftly among languages—English, of course; French, especially for sexual matters; Latin; smatterings of Swedish and German. He rarely mentioned politics. In one entry, written in London, he switched abruptly from English to French, then stayed in that language for pages. It took me a while to realize that he was attempting to disguise his commentary from his prying British landlady, with whom he was having an affair. (Many of the French passages allude to another amorous relationship, lending this theory credence.)

All through the journal, matter-of-factly and with lawyerly precision, Burr documented sexual encounters—from affairs of the heart, often with aristocratic women, to paid trysts, which took place seemingly everywhere, from the parks of Stockholm to Paris’s Palais Royal. Many of these women were not actual prostitutes but young maids and governesses working to bolster their paltry salaries. It was the gig economy, before it had a name.

After Burr returned to America in 1812, he reestablished a private legal practice in Manhattan, picking up the pieces as he could, using aliases here and there to dodge his creditors. Who knows where his European diary spent the next 20 years? All we know is that it survived. After Burr died in 1836, it passed into the hands of one Matthew Livingston Davis, a former law clerk of his who had become a friend and, later, the executor of his estate. Davis was also an editor and a journalist who wrote for newspapers under the tantalizing nom de plume “A Spy in Washington.” He published a two-volume memoir of Burr in the year of his friend’s death. Two years later, in 1838, he edited the journal and had it published in a two-volume edition titled The Private Journal of Aaron Burr During His Residence of Four Years in Europe. It seems safe to say that Burr never imagined that his diary would be available to the public.

As editing jobs go, Davis’s is a salad, with facts tossed wondrously, uninhibitedly, into the air. He rewrote entire passages and added footnotes, some accurate, others not. He eliminated all sexual references—no surprise there—as well as scenes that he deemed unflattering to his friend. Davis included some of Burr’s correspondence in both the memoir and the published diary, and this, too, is problematic. Burr had requested that a group of letters from his various paramours, which he had tied together with a red ribbon, be destroyed. Davis complied. But he also went further, taking it upon himself to destroy other Burr correspondence, too. “I committed [them] to the fire,” Davis reported. Agonizing words! Although he copied some letters (such as those between Burr and Theodosia) before incinerating them, and later published their texts, it’s easy to imagine him changing their language, as he had done in the journal, distorting their meaning in the process. And we can’t know which letters he deemed unworthy of transcription. The loss for historians is incalculable.

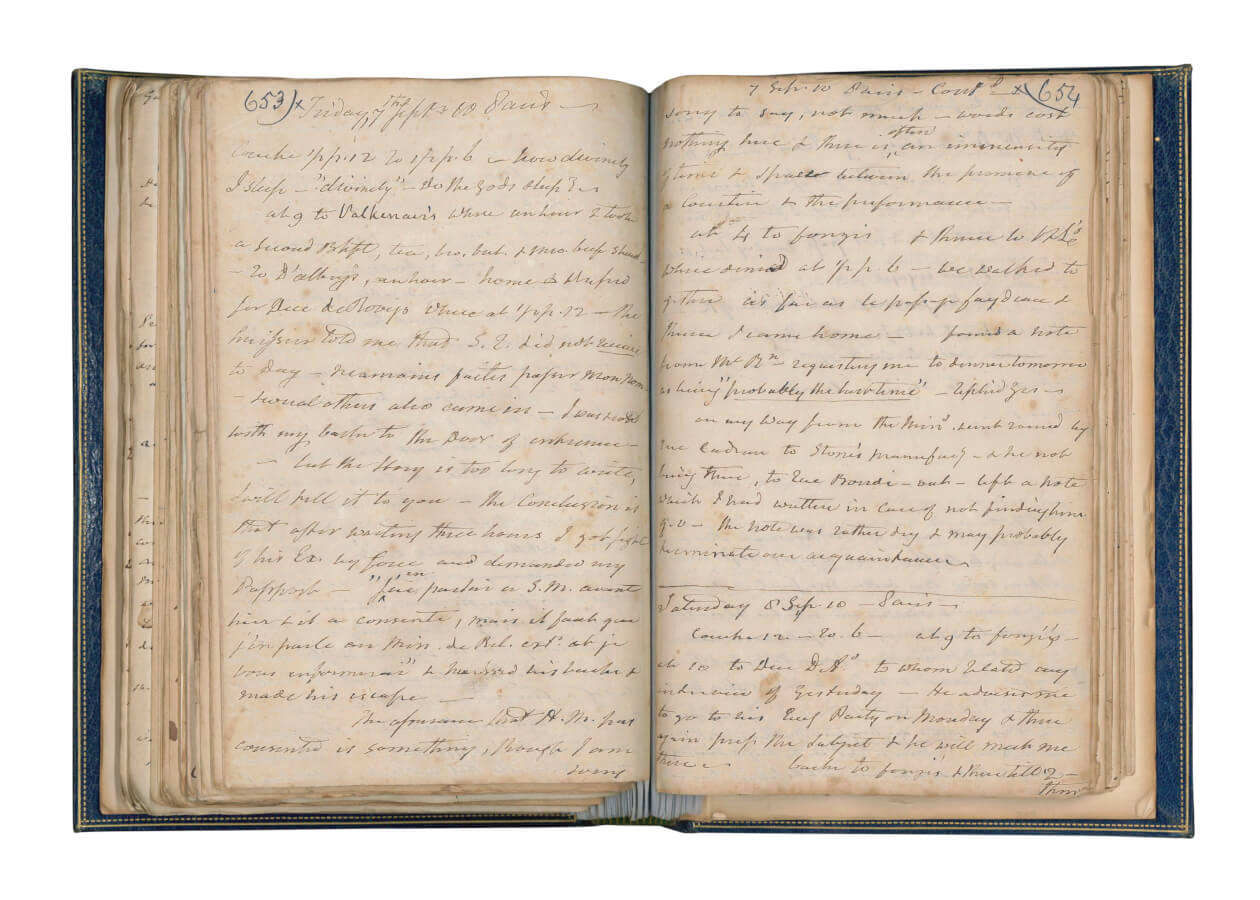

Housed in the Huntington Library, “Burr’s diary exudes a quiet luxury,” expensively bound, the endpapers made of rich brown satin. (Courtesy of the author)

Housed in the Huntington Library, “Burr’s diary exudes a quiet luxury,” expensively bound, the endpapers made of rich brown satin. (Courtesy of the author)

Over the next half century, the diary faded from view. Burr, meanwhile, assumed mythological status. Not in a good way. An anonymous ditty written soon after the duel, and widely heard in subsequent years, gives a sense of the general tone:

O Burr, O Burr, what hast thou done?

Thou hast shooted dead great Hamilton.

You hid behind a bunch of thistle,

And shooted him dead with a great hoss pistol.

Cruel caricatures circulated, including one in which a dark, shifty-looking Burr soaks in a copper bathtub after the duel with Hamilton; he flashes an evil grin, presumably basking in the demise of his rival. He’s rendered so diabolically that he might as well be sporting horns and a tail.

Seventy years after Burr’s death, improbably enough, his diary returned. This time it appeared in uncensored form, replete with Burr’s coded entries about adulterous liaisons, pickups, romantic flings, and ménages-à-trois. This ribald edition of the journal might have been lost to us had it not been for Benjamin Franklin Stevens. As his first and middle names imply, Stevens was an American. He’d resided for years in London, where he was co-owner of B. F. Stevens & Brown, Literary and Fine Arts. Besides his work as a book and art dealer, he also held the title of “despatch agent” for the United States, managing shipments of goods headed to his home country. In 1901, Stevens wrote to a St. Louis lawyer named William Bixby, offering to sell him Burr’s diary manuscript. In the same letter he also warned, in a subtle, throat-clearing kind of way, that it was rather different from Davis’s version, which had been “thoroughly expurgated, and certainly it needs expurgation.”

The mystery of how this manuscript ended up in London was solved in a testimonial included with Stevens’s letter to Bixby. Apparently, the diary had passed from hand to hand, a kind of relay baton. At some point before his death in 1850, Davis palmed it off on Henry J. Raymond, one of the co-founders in 1851 of The New York Times and the paper’s first editor. After Raymond’s death, his widow passed the journal on to her brother-in-law, a lawyer named Robert Benedict, to sell on her behalf. Benedict then brought it to the attention of Stevens, who, writing to the well-heeled Bixby at his summer home in Bolton Landing, New York, assured him that Raymond’s surviving family would welcome “a liberal offer.” Done. (The actual sale price was not disclosed.) The manuscript was soon on its way back to the New World—its third transatlantic crossing. Surely, by now, it traveled first class?

Bixby moved quickly to edit the diary, publishing it as The Private Journal of Aaron Burr in 1903, just a year after he acquired it. Like Davis, he added extensive annotations. Most dramatically, he restored Davis’s cuts, essentially bringing Burr’s sex life to the attention of the public. As he explained in his introduction, libertine behavior was hardly unusual for this time and milieu: “It was a more immoral age than this, many of the prominent men of his time were as fond of gallantries, intrigues, and amours as Burr himself, but he was less disposed than they to resort to duplicity and concealment.”

All through his edit, Bixby bobs and weaves. He scolds Burr for his pidgin Swedish, for writing sloppily, for misspelling proper names. And although the diarist was proficient in French, Bixby—vain about his own command of the language—pounces on any mistake: “Burr has a hard time with this word,” he gravely opines after the latter mistakenly writes “Thulieries” for the famed Right Bank gardens. The editor, though, introduces errors of his own. In one amusing exchange with a Paris acquaintance in the diary, Burr complains of having met “a dangerous siren” and narrowly escaping her seductive wiles. At which point, the “Major laughed at me most heartily and swore I should introduce him, but he has a security which God forbid I should ever [have].” (That “security,” it turned out, was impotence, a condition that can’t have troubled the energetic Burr at that time.)

“Ah Mon Ami, je ne b. plus,” Thomas told Burr. While the b, in this context, clearly stands for the verb baiser—to fuck—Bixby interprets it to mean boire, to drink.

Burr’s response? “Que vous êtes heureux! ” (“Lucky you!”)

Reading this entry in his tiny handwriting, its ink faded to amber, brings a jolt. Does “lucky” mean that he regretted his own promiscuity, even for a minute? If so, it’s the only hint of it anywhere in these scrawled pages.

Bixby may needle Burr, but he heaps opprobrium on Davis, going so far as to describe his earlier version as an “alleged reprint” of Burr’s document. Theirs is a rivalry between colleagues half a century apart. It’s war by footnotes! With their comments and revisions, both editors crowd into the diary, figuring almost as prominently as the colorful characters in Burr’s life: Mariano Castilla and other Latin American revolutionaries; Madame Paschaud, a woman he was in love with who was married to a Paris-based publisher; and the celebrated French engineer Marc Isambard Brunel. Weighing in after the fact—decades later, in Davis’s case, a century on in Bixby’s—the two men enrich Burr’s story, their own disparate sensibilities folded into it like egg whites in a soufflé, expanding it as a result.

America’s founding fathers wrote loftily of the great experiment that would become the United States, coaxing their ideas in words, each one conscious of history being made, and his own central part in it. They speak to us as if from on high, like outsize statues in a distant pantheon. It’s hard to believe they were real. If they appear to be saints, it’s in part due to public relations. Adams, Jefferson, and others worked hard at the end of their lives to present their actions in a positive light, sometimes misleadingly so. Burr, by contrast, took no steps to safeguard his reputation. He didn’t seek to enhance his place in history by recording his own version of past events. He didn’t care. And crucially, he was the only founder without surviving family to burnish his record for later generations. “Burr did not have a protective posterity to project his ‘greatness’ through the ages,” as the historian Nancy Isenberg writes in her 2007 biography, Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr.

Relative to, say, Jefferson, whose collected papers have filled 40 published volumes, and counting, Burr’s writings are scant. Even his famous farewell speech to the Senate on March 2, 1805—said to have provoked tears and rapt admiration in its audience—no longer exists, if it ever did, in written form. Almost all of his pre-1812 papers, which Theodosia had kept for him during his time abroad, were lost six months after Burr returned to America. Theodosia had the papers with her at the time of her death—in a shipwreck off the North Carolina coast in late December 1812. In subsequent correspondence, Burr occasionally mentioned a desire to write a revisionist version of the American Revolution—its true story, he believed—which he had witnessed firsthand as a young officer. But he never followed through. He “came to feel that his history would simply be too shocking,” Isenberg explains.

After Burr’s death, Davis was virtually alone in trying to present the facts about his friend’s life and character. Who else back then would have attempted it? The scurrilous, even evil rumors that surrounded Burr were unceasing. One newspaper, The American Citizen, reported just after his duel with Hamilton that the event had not been conducted according to the terms of the ancient code duello, but rather had been “planned by Mr. Burr and his friends and rigidly carried into execution.” The article added, “He is capable of wading through the blood of his fellow citizens!” Such ceaseless defamations of his character—for as long as he lived and well beyond—made his rehabilitation seem like a lost cause.

Some historians and commentators have, over the years, pointed out how deeply he was wronged. “For a century Aaron Burr has been so persistently and vindictively misrepresented and vilified that he is now commonly regarded as one of the blackest characters in American history,” Bixby wrote in the introduction to his edition of the diary. Twenty years later, Walter F. McCaleb wrote that “measured by the load of obloquy, hate and venom which [Burr] bore without complaint—he stands a colossus.” Isenberg puts it most succinctly: “Everything we think we know about Aaron Burr is untrue.”

Although she and other historians have argued against Burr’s implied guilt, little progress has been made. This point was brought home to me repeatedly, at times even comically, in the course of my research. When I asked the head of an Ivy League library for some Burr-related material, he let slip an almost reflexively disparaging remark—“We all know about him! ”—one that surprised me with its facile assumptions. More recently, a publishing executive, hearing of a proposed Burr project of mine, harrumphed: “Aaron Burr has a lot to account for.”

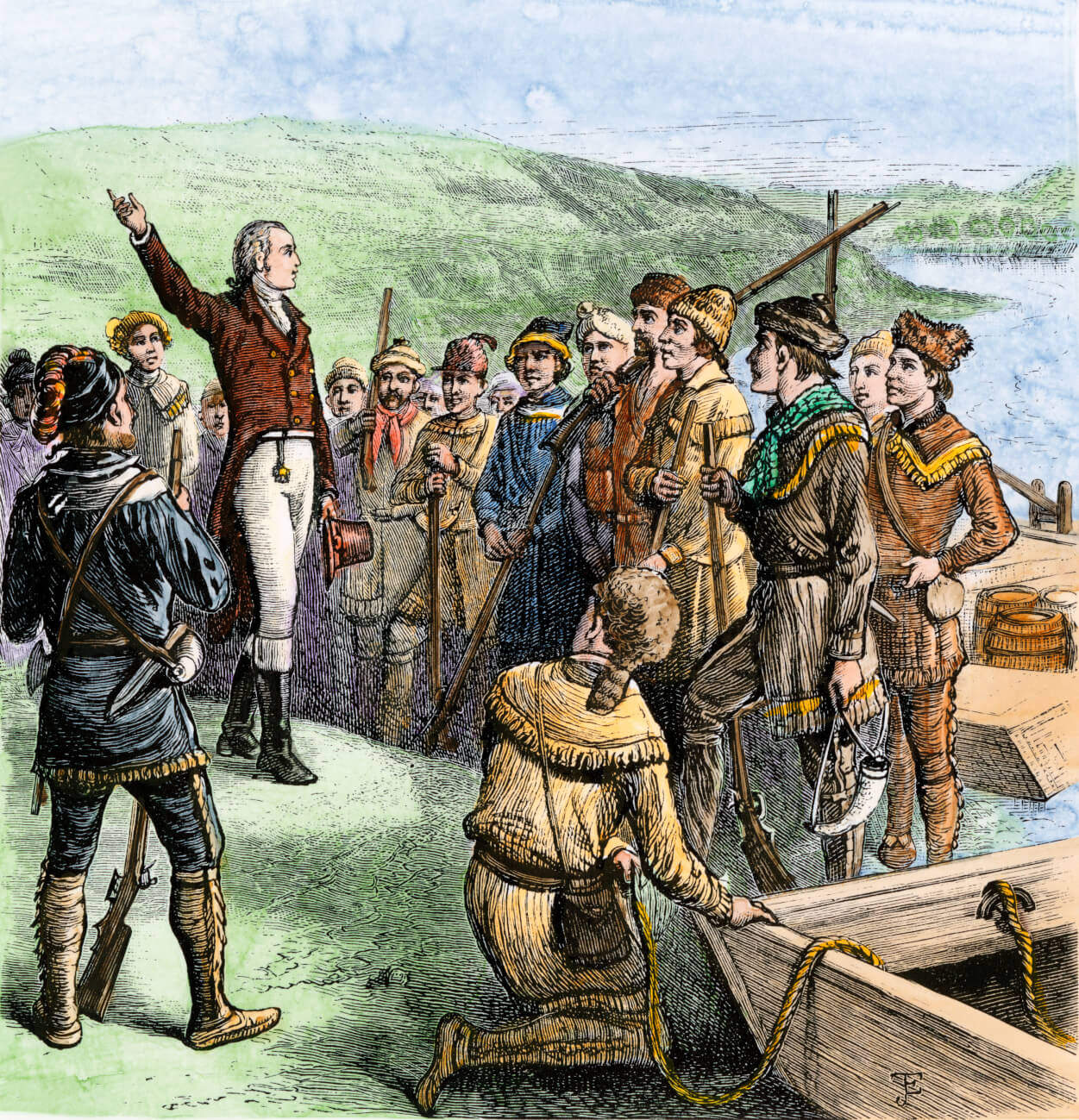

On Blennerhassett Island, on the Ohio River, Burr argues that the western states should be riven from the Union; in three years, he would flee to Europe. (Hand-colored woodcut from the North Wind Picture Archive/Alamy)

On Blennerhassett Island, on the Ohio River, Burr argues that the western states should be riven from the Union; in three years, he would flee to Europe. (Hand-colored woodcut from the North Wind Picture Archive/Alamy)

How richly ironic that although so many of Burr’s writings were lost to the waves, this diary, which had traveled so perilously and so far, survived. Created in a time of grinding poverty, the original now resides in an opulent setting, one of the finest five-star manuscript resorts in all the world: Southern California’s Huntington Library, located on 120 meticulously manicured acres, with lily ponds and more than a dozen gardens, one devoted exclusively to camellias. To visit Burr’s diary in its Shangri-La is a near-religious experience. One floats through the perfumed grounds to the manuscripts division, where assistants bring forth treasures.

In its present incarnation, Burr’s diary exudes a quiet luxury. What a surprise! Its four volumes are lavishly bound—the wealthy Bixby, an avid bibliophile, sought the services of a top bookbinder. Each tome is bound in expensive navy blue calfskin, with accents of tobacco brown. Gold leaf runs rampant. An elaborate, gilded AB monogram adorns each cover. Even the truncated title, Private Journal of Aaron Burr, which appears on the curlicue-festooned spines, seems elegantly understated, even august. The volumes’ endpapers are of rich brown satin; Bixby’s personal bookplate—a print of a shrewd-looking octopus, its tentacles curled around books—is affixed to the flyleaf of each one. It’s quite a transformation for the document Burr once described, with wry affection, as “my ridiculous journal.”

Between the covers, the paper has yellowed, and here and there a red-pencil comment by Davis rises up from the page. The occasional blank spot appears, most often indicating where the editor has erased a proper name. And there’s an extensive gap in the narrative, from mid-February to mid-May 1811, where a volume of the diary must have gone missing.

Is it a stretch to see Burr’s diary in this last incarnation as symbolic of the man himself? The deluxe exterior calls to mind the society figure—the wit, the charmer, the flirt, the seducer—who, born into the American aristocracy, graced salons across upper-crust Europe. The unadorned pages within, with their elegant cursive, suggest the inner man, who remained tranquil as the world closed in on him. Who wrote in the evenings with his daughter in mind, even as he compulsively counted his sous—one to buy an egg for dinner, two for a bottle of Roussillon wine, three for sex.

Bixby published the book in an edition of 250, which he offered to friends and family as gifts. How did they receive Burr’s journal? Did they read it for titillation? Historical value? Both? I can imagine its being handed from reader to reader, as Mary McCarthy’s The Group was passed among my mother’s giggling friends—astonished by the book’s sexual candor—as they sat on a bench in Central Park when we children were small. But who can really know? Erotic or not, The Private Journal was a small project, printed by a vanity press. It didn’t have the artistic stature of McCarthy’s racy novel. It wasn’t literature. It was merely the jottings of a man trying to reach across the ocean to someone he loved. Its existence didn’t matter to the world.

And yet, it matters to us. Few documents are as revelatory as this one about the interior life of an American founder. How fortunate that its author was disinclined to toy with it—or, indeed, anything else—with his own legacy in mind. What a gift! Burr’s indifference to public opinion and the mechanics of reputation is, in the end, our gain.

Almost 40 years after Burr’s journal was published, a copy found its way to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue—the very place that Burr would have called home if the presidential election of 1800 had gone his way. (He tied with Jefferson for the presidency. After 36 rounds of balloting in the House of Representatives to break the tie, Jefferson prevailed. As the runner-up, Burr was named vice president, as the law then decreed.)

In December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt received number 85 of Bixby’s limited edition—perhaps as a Christmas gift?—from an uncle, Frederic A. Delano, a former president of several railroads and, at various times, a member and vice governor of the Federal Reserve Board. “To my distinguished nephew—the President,” Delano wrote on the book’s flyleaf. Why bestow such a present upon the president of the United States? Perhaps there was an element of wink wink, nudge nudge? No doubt FDR’s well-known dislike of Burr’s dueling partner, Alexander Hamilton, added to the gift’s piquancy.

Although Burr has been back in the public eye lately, thanks to a certain hip-hop musical, his journal remains backstage. It seems ripe for rediscovery. Eternally so. These days, both the Bixby and the Davis versions are almost absurdly easy to find online—no need to pay a fortune for a numbered edition. Still, it seems likely that they won’t be the diary’s final iterations. And there will surely be other interpretations of the text to come. Burr’s story will be reinvented, in ways subtle or not, each time. A message in a bottle, never quite reaching shore.