Abolition Gone Wrong

Despite good intentions, some opponents of the Atlantic slave trade caused more harm

Ship of Death, Billy G. Smith, Yale University Press, 328 pp., $35

The Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World, Greg Grandin, Metropolitan Books, 384 pp., $30

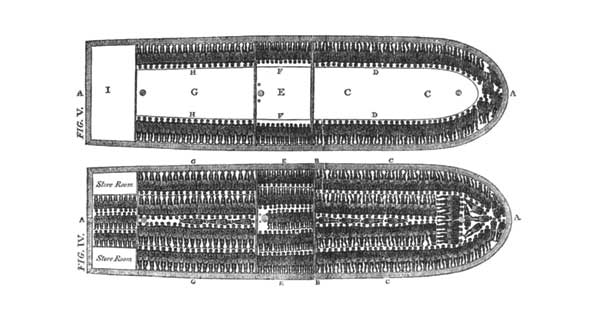

The Atlantic world of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was an age of often unspeakable brutality, sudden and inexplicable death, and ubiquitous threats from invisible microbes, deadly climates, and the caprice of the seas. Added to all this, in much of the world the special barbarism of slavery infected great swaths of domestic, agricultural, and commercial life. The complexities of enslavement and the moral dilemmas that beset those who opposed it are explored with both power and originality in two vividly written new books. Both hinge on long-forgotten maritime events, but reach far beyond the particulars to illuminate in new and sometimes startling ways the context of their time.

In Ship of Death, Billy G. Smith recounts the tragic tale of the Hankey, a ship leased in northern England in 1792 by idealistic abolitionists to transport British settlers to a proposed interracial colony on the west coast of Africa. The constitution of the “Bolama Association,” as the Hankey’s initial owners called themselves, after the island off the coast of Guinea that they planned to colonize, was a remarkably radical one: it outlawed slavery, mandated universal male suffrage regardless of race, and pledged that its members would settle only on lands they could purchase from local people—a dramatic departure from the seizure of territory elsewhere in Africa.More than 200 men and women signed on. They were a diverse and democratic lot, including freethinkers, Jews, both working class and socially elite, and anglicized former slaves.

They were also delusionally naïve. They knew virtually nothing about Bolama, whether anyone already owned it, what its soil and climate were like, or how to survive in the tropics. Writes Smith, each settler “flattered himself with the pleasing idea of acquiring, by his industry, a sufficient fortune to enable him, in a short time, to return to his native country in a state of independence.” The first colonists swarmed ashore believing that they had landed on an uninhabited island, and that whatever natives lived in the vicinity would welcome them as brothers. But the island’s irate owners soon appeared and promptly killed several of the hapless new arrivals.

To their credit, the colonists overcame their initial shock, negotiated the purchase of the island from wary tribal leaders, and began clearing land. Everything went downhill after that. Elephants trampled their gardens. Their livestock—oxen, donkeys, sheep, and goats—were devoured by large cats and hyenas. And they learned that a tribe on the mainland also claimed ownership of the island, compelling the settlers to purchase it a second time.

The colonists soon discovered, to their dismay, that the local peoples had no interest in their version of “civilization.” Smith writes, “Their ingratitude astounded the Europeans, whose paternalism was often matched only by their self-righteousness.” In effect, the colonists were settling an Africa that existed mainly in their own imaginations. Writes Smith, “The incidents at Bolama were a stark reminder that much of European and subsequently American expansion, even in our own times, has operated in a similar vacuum, with more tragedy than triumph.”

One thing that Bolama provided in abundance was monkeys. They filled the trees, were easy to kill, and made tasty dining. “What [the settlers] did not know, and what would not be understood for another century, was that these monkeys harbored a vicious strain of yellow fever, circulated among them by mosquitoes that infested the mangrove swamps,” Smith writes.

Within a few months, all but a handful of the colonists were dead or had fled back to England. The Hankey then zigzagged across the Atlantic, collecting what cargo it could and dispersing yellow fever–bearing mosquitoes and death wherever it made landfall. In 1793, it reached the U.S. capital in Philadelphia, where the fever killed 5,000 people in a matter of months and forced the government to flee to safety in the countryside. Bolama Fever, as it was called, would continue to visit eastern port cities for years to come. Thomas Jefferson, who preferred a purely rural nation of yeoman farmers, predicted, “The yellow fever epidemics spelled the doom of large cities.”

The Empire of Necessity delivers an even more remarkable story, one that unravels the American encounter with slavery in ways uncommonly subtle and deeply provocative. The book’s core is an unpacking of the historical events that inspired Herman Melville’s 1855 novella, Benito Cereno. In Melville’s telling, an American vessel encounters a ghostly ship adrift off the Pacific coast of South America, its Spanish captain mysteriously dominated by a menacing black man who appears to be his servant but is revealed as the leader of mutinous slaves who have taken over the ship.

Melville’s novella, Greg Grandin observes, has generally been treated by scholars as “a parable of the cosmic struggle between absolute virtue and absolute evil.” He cogently argues instead that it seems “unrelentingly to be about one thing, the most divisive subject in American history: slavery.” Grandin’s book, then, is not just about history, but implicitly also about scholarly evasion.

Melville’s fiction was based on the memoir of Amasa Delano, an antislavery Yankee from Duxbury, Massachusetts, and the commander of a seal-hunting expedition, to whom all this actually happened, in 1805. The revolt took place on the Chilean-owned Tryal, which was carrying a cargo of slaves to Peru. The captives overpowered the crew, killed most of them, and ordered the survivors to take them back to Africa. In hope of somehow being rescued, the whites deliberately sailed in circles for weeks, until they finally encountered Delano’s Perseverance. For an entire day, the Africans performed a charade, pretending to be slaves again in order to obtain fresh water and supplies from the Americans. When Delano discovered the truth, he ordered his men to take the Tryal by storm. After its capture, his men—some of whom may have shared Delano’s “enlightened” views on race—disemboweled and skinned several of the mutineers, leaving them to die in horrible agony. Afterward, Delano took the surviving slaves to Chile, where profits from their sale became part of the prize money his crew claimed for returning the ship.

Melville’s fiction was based on the memoir of Amasa Delano, an antislavery Yankee from Duxbury, Massachusetts, and the commander of a seal-hunting expedition, to whom all this actually happened, in 1805. The revolt took place on the Chilean-owned Tryal, which was carrying a cargo of slaves to Peru. The captives overpowered the crew, killed most of them, and ordered the survivors to take them back to Africa. In hope of somehow being rescued, the whites deliberately sailed in circles for weeks, until they finally encountered Delano’s Perseverance. For an entire day, the Africans performed a charade, pretending to be slaves again in order to obtain fresh water and supplies from the Americans. When Delano discovered the truth, he ordered his men to take the Tryal by storm. After its capture, his men—some of whom may have shared Delano’s “enlightened” views on race—disemboweled and skinned several of the mutineers, leaving them to die in horrible agony. Afterward, Delano took the surviving slaves to Chile, where profits from their sale became part of the prize money his crew claimed for returning the ship.

Grandin interweaves his account of the events on the two ships with finely braided explorations of the Atlantic slave trade, the culture of enslavement in South America (which differed in some striking ways from the U.S. version), early abolitionism, the appallingly cruel business of seal hunting, and the larger struggle of mariners to wrest a living on ships where captains exercised “terrific sovereignty” over their crews, resorting to flogging for even minor infractions. “No southern monarch of the slave,” wrote one sailor in an 1854 account, could best the “brutality” and “want of moral principle” of sea captains. Grandin also underscores the significant though largely unacknowledged presence of Islam in the Americas, in the persons of hundreds of thousands of Muslim slaves, many of them literate in Arabic, probably including several on the Tryal, whose “strong egalitarian ethos and sense of justice,” he suggests, may have been an uncredited factor in many slave rebellions.

Both the Yankees of the Perseverance and the slaves of the Tryal, Grandin says, were victims of the unforgiving commercial imperatives of their time. In one particularly penetrating passage, he compares Amasa Delano to Ahab of Moby-Dick. Both, he writes, were “agents of two of the most predatory industries of their day, their ships lugging the ‘machinery of civilization,’ as the real Delano put it, to the Pacific, using steel, iron, and fire to kill animals and transform their corpses into value on the spot.” Of Delano, Grandin writes, “Caught in the pincers of supply and demand and trapped in the vortex of ecological exhaustion, with his own crew on the brink of mutiny because there are no seals left to kill and no money to be made, Delano rallies men to the chase, not of a white whale but of black rebels.”

Grandin aptly quotes Hegel’s observation that it wasn’t “so much from slavery as through slavery that humanity was emancipated.” At the turn of the 19th century, as both Grandin and Smith show, countless “free” inhabitants of the Atlantic world were shackled morally, economically, and politically to slavery. In antislavery New England, banks capitalized the slave trade and insurance companies underwrote it, plowing their profits into other northern businesses, helping to make fortunes for merchant families in many Yankee ports. Even those who sincerely opposed it, such as Amasa Delano—the quintessential right-minded American, a man with an unshakable “faith in the idea of self-mastery and self-creation,” a faith that, Grandin drily comments, “is repeatedly proven to be misplaced”—were entangled in its web. It would take much more effort, and much more blood, to liberate both the enslaved and the free from the shackles of bondage.