Adventures With Jean

Striking up a friendship with an older writer meant accepting the risk of getting hurt

I lived in New York City when it was more violent and dangerous than it is now. Needle Park was still a place where people were killed and women were raped, and the Lower East Side was a place where you wanted to be careful. Mobsters shot each other in the city, as in Joey Gallo getting gunned down in Umberto’s clam bar in Little Italy. Morningside Heights was a place to avoid after dark, and Harlem wasn’t as friendly as it had once been. It is hard to evoke the mood of New York in the early 1970s, but it had a whiff of Belfast about it, violent, poor, and seemingly unchangeable.

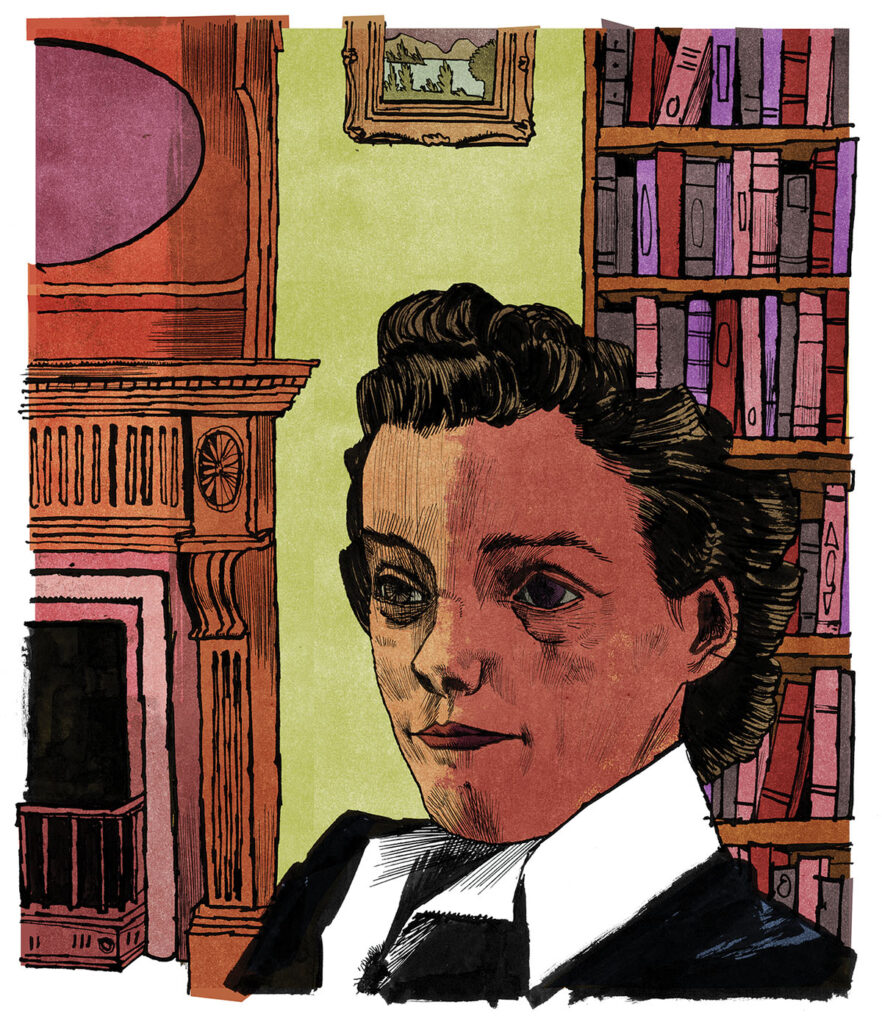

In those days, I was a graduate student in the newly established MFA program at Columbia, where the novelist and short story writer Jean Stafford was one of my teachers. Jean was in her 50s, slender, her hair short, her face scarred from an automobile accident that her first husband, Robert Lowell, had gotten her into in 1938. He had crashed their car into a concrete embankment, leaving her not only with a scar on one side of her face but also with a broken nose that never properly healed.

My shyness came into play—although I wanted to make friends, I didn’t really know how. Jean was from a different world, accomplished, elegant, and aware of life in a way that I wasn’t. She had taught a class in a building on 110th Street that at one time had been a women’s hospital. (One of my classes was held in its former operating theater, and a woman who sat next to me said, “Shit, you know what? I had two kids in this room.”) The classroom where Jean taught had a view of a courtyard that the university was using for storage. One December day, it began to snow. Having recently arrived from California, I was seeing snow for the first time—it was impossible not to stare out the window. After class, I said to Jean, “I’m sorry that I was distracted in class, but I had never seen snow before.” Her expression was one of delight and keen distress, as though she were thinking of some moment from her past. We went to her office, and she told me she had grown up in Anaheim, on a piece of land that her father had owned and run as a citrus grove, and that Disneyland had been built there.

I approached our relationship with tentativeness, and with the certainty that she would hurt me. Getting to know her seemed risky for us both, given the difference in our ages. She had been married three times—her last marriage, to A. J. Liebling, ending with the journalist’s death in 1963. I thought that maybe I should just leave her alone. Still, I spent time in the renovated outbuilding behind her house in East Hampton, where she and Liebling had lived until his death and which she called the “chicken coop,” since that is what it had been. The two-story, 19th-century main house was faded and sedate, and when I first saw it, it seemed a little Dickensian. Not quite like Mr. Wemmick’s castle in Great Expectations, but Victorian and surprising. Downstairs, the house had a kitchen, a living room, a back parlor, and a bathroom. Jean’s office was upstairs, and one bedroom was there, too, although the two other bedrooms had been made into offices, since Jean didn’t want any overnight guests in the house. Only in the chicken coop.

Jean could be forgiving, but she was also demanding, and I knew that if my reaction to a subject was clumsy or not thoroughly considered, we would both be injured. How to be a good friend to someone 30 years older who had suffered through two bad divorces and the death of a third husband? I loved her in many ways, but when I was with her, I was often terrified. When I sat opposite the scarred face of a once beautiful woman who had been hurt by so many people, I was honest but cautious, too.

We drank in her living room, Jean in a comfortable chair and me on a blue horsehair sofa. Jean laughed and told me stories—she liked to tell stories, though at the heart of them was often a cheerful dismay at the things that had happened to her. And what was I to say? With each story, we were slowly becoming friends, much to my pleasure and amazement. She trusted me, and I didn’t want to do anything to interfere with that trust.

She told me of her hysterectomy, performed by a southern doctor who had said, “Don’t you worry, Miss Jean. You can go on having sexual intercourse with all your friends.” Jean loved to assume the accent of the people who appeared in her stories—particularly southerners. She liked to tell of the time she and Liebling had visited with Earl Long, the governor of Louisiana, imitating Long’s drawl with a drink in one hand and a cigarette in the other.

She told me many stories about her marriage to Lowell. Once, she went to see him in a quiet asylum in upstate New York, where he thought he was Napoleon. When Jean arrived, he was drilling his troops, and one of his generals was Judy Garland. She told me this with an air that conveyed both a cheerful sense of the ridiculous and a feeling of profound dismay. Then there was the time Lowell wanted to become a Catholic and insisted that Jean go to early Mass with him. When she had done this for a year or more and decided she couldn’t do it any longer, she told Lowell that she was going to leave him. He said, “Don’t worry, Jean. We can stop going to Mass. I’ve got the vocabulary now.”

As a wedding present, Lowell’s mother had given her a plot in the family cemetery, but after the divorce, Mrs. Lowell wrote to ask for the plot back. Or, as Jean said, with that laugh of dismay and amazed cheer, “My remainders were no longer welcome.”

I laughed with her in complete amazement that such things had happened, but also so that I could convey how much I really cared for her and how flattered I was that she liked to be with me.

In 1973, Jean wrote an op-ed for Newsday, for which, she said, she had not been paid. In lieu of sending her the $250, the newspaper gave her a sort of runaround, saying that as a proof of goodwill, her fee hadn’t been reported to the IRS—as though this compensated for not being paid at all. I was living in the chicken coop for a week, and I said that I would serve as her attorney and sue Newsday in small claims court for the $250 plus some expenses. She was happy for me to do this, and so I went to the courthouse in East Hampton and obtained a summons, which we then had to serve on Newsday.

On a hot summer day, we got into her blue Chevelle, Jean with a scarf over her hair and wearing dark glasses and me behind the wheel. She touched the scars on her face and said, “How is your driving?” This was after I had been a cabdriver in New York, and so I could say in all honesty, “Never better.” We drove through the heat of Long Island to Riverhead, the window down, Jean’s scarf blowing in the wind, her expression one of delight taken in a little old-fashioned mischief. Since delight is contagious, I was delighted, too, although I wasn’t sure why.

I pulled the Chevelle into the parking lot and got out with court papers in hand. Jean sat in the car, smoking a cigarette, keenly alert to the possibilities. The door of the Newsday building was one of those institutional aluminum-and-glass items that seemed a little dreary, or maybe just opaque. The receptionist sat behind a piece of glass with a hole in it, like a cashier in a movie theater. The barrier had a lot of space under the speaking hole, and I knew that if you served papers on someone, you had to touch the recipient with the summons.

In the car, Jean said, “What happened?”

“I reached in and touched the receptionist with the papers, and she said, ‘You can’t do this,’ and I said, ‘I already have.’ ”

Jean said nothing, but that small, slight, deep smile was right there. As we drove back to East Hampton, Jean smoked a cigarette, her expression that of a prison escapee temporarily on the loose, one who knows she will be caught again.

“Let’s go home and drink up a storm of beer,” she said.

But it all came to nothing. The next evening, when I went to have a drink with her, Jean was crestfallen. She apologized to me for having “blabbed” about our adventure to the editor of The East Hampton Star. We decided to let the matter go, despite how much fun we had had.

One evening, Jean told me of the time when she and Liebling went to the races in England. They had taken a chauffeured car, and Liebling had packed a hamper of roast pheasant and excellent white wine. I told her some stories about Los Angeles, and what my life was like in New York City. She had more to drink, and then got out a recording of Peggy Lee’s “Is That All There Is?”

Before she played it, she said that she had been on the set of The Misfits, the movie with Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, and Montgomery Clift. She turned to me with that look of dismay and slight grief. She said that when she was introduced to Clift, he responded, in a halting, impressed sort of way, “Oh, how nice to meet you. I have all your records.” He had confused her with the singer Jo Stafford. Then Jean played “Is That All There Is?” As she listened, she got up and danced, swaying in time to the music, eyes closed, heartbroken, longing for Liebling, I thought, longing not so much for another place as for another time. And as her friend, I was left with uncertainty as to what I should do. I felt as if I could see years of pain in every line in her face, in the scars from the accident with Lowell, as well as what it might be like to spend a life trying to write well. I wasn’t old enough to understand the passage of time, the nature of disappointment, and endless regret. And so I sipped my drink, kept my eyes on her, and let her dance without judgment or comment, without anything but my admiration and affection.

When she had a stroke a few years later, I called her from the city, tried to talk to her as though nothing was wrong, but she couldn’t really speak, and I could sense in her silence and in her slight stutter that things were not right. I wanted to protect her dignity, since she was proud, and yet there are times when dignity only makes for loneliness, although I didn’t know that at the time. I told her that I would do anything I could for her, if she needed something done in the city. I still don’t know if this was the right thing to say. Perhaps I should have said, “Oh, Jean, I’m coming to see you. I’ll be there soon.” I wish I had, but our mutual reticence in this moment made it difficult.

When I went to the graveyard in East Hampton in 1979 and found the headstone that read, Jean Stafford Liebling, I felt the ache of those times when we were together, when the risk had been so high and the affection so great. There was a rumor that I was her illegitimate son. At the time, whoever started this did so out of malice, but when I stood by the headstone, I realized how much I had wished it to be true. It is a rare item to have malice turned into pleasure.

The New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg once joked that Jean’s scarred face was the product not of a car crash but of a “cheap nose job.” Jean had laughed when telling me this, and I had laughed, too. When I stood by her headstone, I could almost hear that laughter, so wise, so vital, and so hurt.