All of us remember the favorite books of our childhoods. That’s when stories affect us most, giving us a glimpse of the world beyond our bedroom walls or presenting various options for the kind of life we might aspire to. As a boy, I frequently reflected on the respective merits of becoming a dashing riverboat gambler, professional private eye, or treasure-seeking pirate. There always seemed to be lots of money in these reveries, and, as I grew a bit older, a number of slinkily attired women too. These last often resembled certain female classmates of mine, except that the silken dream lovelies, unlike the classmates, actually seemed interested in me.

All of us remember the favorite books of our childhoods. That’s when stories affect us most, giving us a glimpse of the world beyond our bedroom walls or presenting various options for the kind of life we might aspire to. As a boy, I frequently reflected on the respective merits of becoming a dashing riverboat gambler, professional private eye, or treasure-seeking pirate. There always seemed to be lots of money in these reveries, and, as I grew a bit older, a number of slinkily attired women too. These last often resembled certain female classmates of mine, except that the silken dream lovelies, unlike the classmates, actually seemed interested in me.

In my own case, I particularly loved boys’ adventure books and comics. Certain names are holy even now: Uncle Scrooge, Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, Rick Brant and Ken Holt, Green Lantern, The Flash, Jules Verne, The Hardy Boys, Dr. Fu Manchu, Robert A. Heinlein, King Solomon’s Mines, H. P. Lovecraft, Lord Dunsany. We never do read again with that wonderful, breathless excitement that is ours at 14, the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Mystery, and Romance.

Or do we?

I was thinking back recently to some of the books I discovered in later years, at college and in my 20s, that do seem to me comparably life-changing. We should, I suspect, be wary of over-mythologizing early reading at the expense of more grown-up books. As Randall Jarrell pointed out, in a Golden Age people usually just go around complaining how yellow everything is.

In college, for instance, I was idly wandering through Oberlin’s co-op bookstore one afternoon when I noticed a paperback with a big number 7 on an otherwise white cover. I picked it up and began to read William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity. For me, as for many others, the book came as a revelation: beneath the surface of a poem there crackled unsuspected energies, connections, and meanings. The scales drop from my eyes—and suddenly I could see poetry.

As a junior I enrolled in a one-semester French course devoted to reading, in its entirety, Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. Our teacher, Vinio Rossi, doubtless underestimated the time it would take for 20-year-olds to work their way through three thick Pleiade volumes. But I was enchanted by the classic simplicity of that well known opening line—“Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure” (“For a long time I went to sleep early”)—and completely seduced by the languorous beauty of Proustian prose. Most of all, though, the almost stand-alone novella, Un Amour de Swann (Swann in Love), seemed written for me. Is there a better account in literature of sexual enthrallment? I was then madly infatuated with a Titian-haired beauty who seemed a lot like Odette de Crécy. I, too, knew the racking torments of jealousy and possessiveness. In the end, of course, Swann recognizes that he has spent years of his life, even wanted to die, over a woman who was, he finally realizes, “not my type at all.”

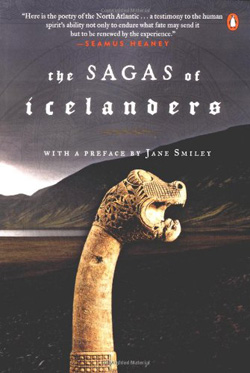

During my early years in graduate school, my main interest was medieval literature. Which explains why, in a happy moment, I signed up for a course on the Icelandic saga. I didn’t really know much about Northern Literature, which I then basically associated with myths about Loki and Thor, marauding Vikings, and Wagner’s Ring cycle. But the Laxdaela Saga, Grettir’s Saga, and Njál Saga swept me back into a world of adventure not unlike that of Clint Eastwood’s spaghetti westerns, only with swords, in the winter, on ice. The foster son of Njál, the lone survivor of a massacre, methodically tracks down the 40 men responsible for the destruction of the only family he has ever known. Cursed by a demon, Grettir—the strongest warrior in Iceland—suddenly finds himself afraid of the dark. I soon read every saga I could find, and there are quite a few of them. A hefty one-volume compilation is The Sagas of Icelanders, with a preface by novelist and fellow fan Jane Smiley.

In graduate school I also discovered that certain scholarly books could produce an intellectual exhilaration that rivaled the more visceral thrills of childhood reading. Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature made me wish to become an erudite, multilingual, European polymath. I soon realized that was never going to happen, though one could still, in a small, provincial way, try. Peter Brown’s Augustine of Hippo brought the fourth century and its philosophical crosscurrents to blazing life. We all know about the young Augie’s famous plea, “Lord, make me chaste, but not yet.” What Brown’s book does, however, is reveal the astonishing evolution of that capacious, world-altering intellect, and he does so in an unputdownable page-turner. Because of Augustine of Hippo, late antiquity came to seem as exciting, as revolutionary and ideologically riven, as the 1960s.

In fact, for a long time biographies and autobiographical books replaced novels as my favorite genre. Rousseau’s Confessions swept me away with its limpid prose-poetry, and I’ve never forgotten many of its episodes, in particular the evening Jean-Jacques entertains a celebrated Venetian courtesan. When this toast of the canals disrobes, he notices a small blemish on her breast and slightly recoils. Immediately, she gathers up her clothes and dismissively sends him on his way with a brusque, “Lascia le donne e studia la matematica!”—“Give up women and study mathematics!”

In my late 20s, I devoured Richard Ellmann’s James Joyce, the portrait of the modernist as a literary saint, Rupert Hart-Davis’s underappreciated Hugh Walpole, a stunning depiction of an ambitious young writer on the make during the early 20th century, and S. Schoenbaum’s Shakespeare’s Lives, which tracks the multiple ways we have imagined and distorted the biography of our greatest playwright. All these were utterly riveting, and remain among my favorite books to this day.

In my 30s and after, the books that seemed to catch me at the heart or change my inner life grew fewer, but there are at least a dozen. Gilbert Sorrentino’s Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things, for instance, and Casanova’s memoirs. But they will keep for another day, another column.

According to Longfellow, a boy’s will is the wind’s will, and the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts. So even now I keep a deck of cards at my desk and sometimes practice dealing seconds. There’s a rumpled trench coat in the closet, and I’m on my guard around dames named O’Shaughnessy. Not least, I’ve made sure that there’s a black flag displaying the skull and crossbones neatly packed away in a dresser drawer, just beneath an old French mariner’s sweater. Who knows? Someday, yet, I may still hoist the Jolly Roger.