Ahead of the Game

Before exercising the right to vote, women fought for the right to exercise

“Good health practices and unrestricted physical mobility [are] critical components of an emancipated womanhood.”

—Patricia Vertinsky

The origin of the modern women’s movement is the subject of countless books, monographs, and scholarly articles. The History of Woman Suffrage, by Susan B. Anthony and others, was published in 1922 and spilled over six fat volumes. This year’s centennial of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment—August 18—has inspired a number of anticipatory new books, including Susan Ware’s Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote (2019) and Ellen Carol DuBois’s Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote (2020). In July, the Library of America published American Women’s Suffrage, a collection edited by Ware.

Of course, gaining the right to vote is just one aspect of a much larger story with a much longer history, and there is no single starting point for feminism. It didn’t emerge from a single event, the way the universe did. My own focus as an independent scholar has been on women’s growing presence in what had long been, and often still are, male-dominated sports. Whatever the many strands that would ultimately weave together the women’s movement as it developed in the mid- and late-20th-century, women in sports is certainly one of them. Women’s success at competitive and other kinds of sporting activity, accelerating in the 1870s, showed women to be strong, level-headed, and skillful—refuting the long-held Victorian construct of women as frail, hysterical, and passive. Women were a mainstay of the so-called physical culture movement, which combined exercise, a healthy diet, and large doses of religion into robust regimes of self-empowerment. As women took up strenuous physical activity, their clothing had to change. You couldn’t compete comfortably, or successfully, while wearing shackles, which is what women’s clothing had effectively become.

My research in recent years, in service of a book on this subject, has led me increasingly into photographic archives—some well-known, some obscure—of images both candid and posed. I find that my own reactions shuttle between admiration and amusement—the reaction, no doubt, that observers in the future will have, if we are lucky, when they confront archival photographs of our own era. I present some of the photographs from this scrapbook miscellany here.

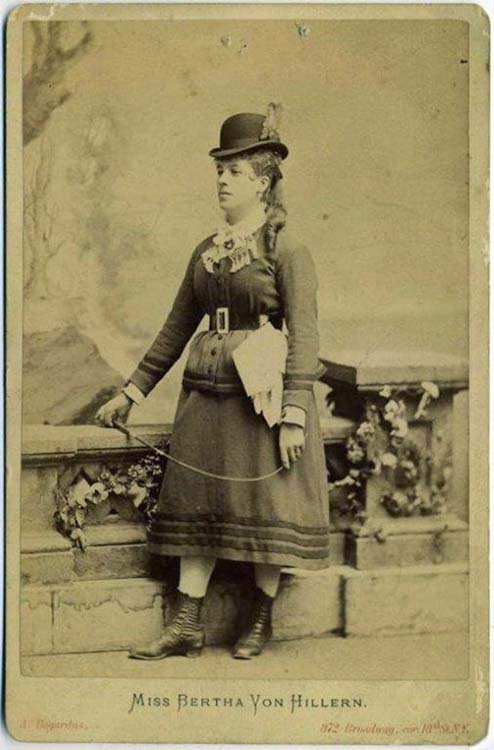

During her two-year career as a pedestrienne, Bertha von Hillern, shown here in 1877, headlined 25 walking events in 15 cities. Newspapers described her as “a fashion icon,” a “lady of refinement,” and “one of the wonders of the nineteenth century.” (findagrave.com)

The sport known as pedestrianism became popular in the U.S. after 1861, when a Rhode Island bookseller walked from Boston, Massachusetts, to Washington, D.C., in 10 days. Soon many towns had an indoor walking track, with one lap measuring an eighth of a mile around. Competitors walked for up to six days at a time, with periods of rest (not to exceed three hours at a stretch) taken on small cots set up alongside the track. Women walkers—pedestriennes—became prominent, drawing thousands of spectators to witness their endurance and their outfits. One of the most renowned was German-born Bertha von Hillern, who emigrated to the U. S. from Germany in 1876 on a mission to promote her own system of physical culture, one that emphasized the importance of vigorous exercise for women. Von Hillern, born to a German military family, exuded a dignified strength that earned her the approval of progressives and traditionalists alike. It also made her some money. After two years of competition, Von Hillern decamped to Boston to study painting with the celebrated artist William Morris Hunt.

In 1914, Esther Stace cleared a 6’6″ fence riding sidesaddle at the Sydney Royal Easter Show in Australia, establishing a record that has yet to be broken. She accomplished it with the help of a sidesaddle device called the Leaping Head—a curved pommel that anchored her left leg, stabilizing her seat. (Walcha and District Historical Society, Australia)

Starting in the early 1800s, equestriennes dressed in long skirts and riding sidesaddle tackled hunt courses and often beat male competitors wearing breeches and riding astride (“like clothes pins”). By 1886, with the formal establishment of fox hunting packs in Westchester County and on Long Island, women began competing as equals with men in the dangerous equestrian sport of riding the hounds, where their long skirts and sidesaddles put them in danger of falling and suffering serious injury. Victorian America considered sidesaddle the only proper option for women riders, but it made jumping a challenge: keeping both legs on the left side of a horse unbalanced the rider as well as the mount and made it impossible for a rider to communicate with the horse using her legs. And in a fall, women were rarely thrown free, the way men were; they often ended up pinned beneath the horse. But the women were skilled: contemporary newspapers reported men suffering proportionately more life-ending injuries than women during the hunt season.

Growing up in Southern California, Florence Sutton—shown here at the 1911 U. S. Tennis Finals, in Newport, Rhode Island—and her two sisters all played competitive tennis. Tennis outfits became less restrictive and fashionable after 1920, when Suzanne Lenglen appeared in the short-sleeved, below-the-knee dress created exclusively for her by the French designer Jean Patou. (Library of Congress)

The racket sport we recognize as lawn tennis has been played by British aristocrats since 1859 and was introduced to America in 1874 by Staten Island resident Mary Ewing Outerbridge, who had learned to play in Bermuda. Women and men took up tennis at the same time. But women’s attire could prove troublesome. In 1884, British player Maude Watson won the first ladies’ championship at Wimbledon after one of her competitors, wearing a corset and long skirts, fainted in the heat. (Tennis officials presented the episode as evidence that women did not have the strength to play five-set matches.) America’s Sutton sisters, who began competing as youngsters in Southern California around 1901, proved them wrong. May Sutton became the first American to win a singles title at Wimbledon in 1905, and Florence, pictured here, became a U.S. Open finalist for both singles and doubles in 1911. Luckily for the Suttons, women’s tennis outfits had become more relaxed by then: white cotton shirtwaist, ankle-length skirt. But there were lines you could not cross. At Wimbledon in 1905, 17-year-old May Sutton raised eyebrows when she rolled up her sleeves. The judges stopped the match until her sleeves came down.

This young fisherwoman asserts her rights to wear pants and to fish like a man in Yellowstone in 1895. Her location was most likely the banks of the Firehole River, which remains one of the premier locations for trout fishing in North America. (Collection of Barbara Levine, San Francisco)

Well-to-do American women had been fishing since the mid-1870s, but Maine’s Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby set a special example by deliberately choosing life in the wilderness over a more conventional existence. Both her father and brother had died of consumption, and Crosby herself suffered from poor health her whole life. On the advice of her doctor, Crosby left her bank job in her hometown of Phillips, Maine, for the state’s northern woods in the early 1890s. She never looked back. In 1898, Crosby gave a shooting and fly-fishing demonstration at New York’s Madison Square Garden, dressed in a calf-length leather skirt. Soon she was writing a syndicated column titled “Fly Rod’s Notebook.” Crosby’s descriptions of her fishing exploits introduced women to the sport and attracted thousands of tourists to the Maine wilderness. As the state’s first female guide and an independent woman promoting the health benefits of outdoor activities, Crosby became a role model for women nationwide. Ever modest, she once said, “It is the easiest thing in life to describe me. I am a plain woman of uncertain age, standing six feet in my stockings … I would rather fish any day than go to heaven.”

Women enthusiastically took up golf in the 1890s, dressing in long skirts and day blouses with tight sleeves like these golfers in Dansville, New York, in 1900. Sartorial change would not come until 1904, when British designer Thomas Burberry introduced the Free-Stroke Coat and a drawstring skirt whose hem could be raised. (Library of Congress)

In the 1890s, socially prominent women began taking up golf—and excelling. Ladies’s champion Beatrix Hoyt fit the social profile: she was a descendant of Thomas Jefferson and her mother, Janet Chase Hoyt, was a co-founder of Shinnecock Hills, the iconic Long Island golf course. Hoyt proved herself a maverick by virtue of her playing style, excelling at short, precise iron shots with a swing like that of a Scottish pro. Early on, Hoyt found herself outdriven by most opponents, but she added length to her tee shots by modifying her follow-through. She also broke with convention in her sartorial choices. While her opponents played in floor-length dresses, with hats and gloves to protect them from the sun, the often hatless Hoyt wore a shorter skirt so that she could better see the ball at her feet. Hoyt was also in her teens, and up against opponents twice her age. She had been playing for less than two years when she won her first Women’s Championship at Morris County Golf Club, Morristown, New Jersey, in 1896. She’d been taught by the best: the legendary Scottish golfer Willie Dunn.

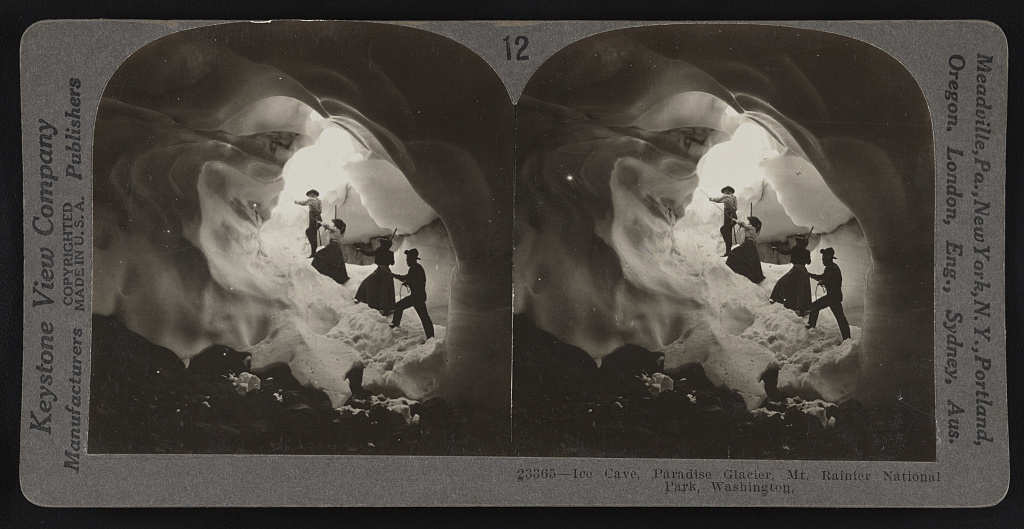

Starting in the late 1890s, women and men alike flocked to newly established national parks like Mount Rainier in Washington. Here, in a stereograph from around 1923, intrepid women in long skirts joined their male companions on Mount Ranier’s Paradise Glacier. (Library of Congress)

Propriety dictated that women wear long skirts—supplemented by woolen underwear and nailed boots—even in the wilderness, but restrictive garments did not discourage them from scaling mountains or hiking glacial ice fields. On the East Coast, wealthy New York families established Great Camps in the Adirondacks. On the West Coast, people of means traveled by train and stagecoach to national parks. Outing Clubs included both male and female members (seven women were among the co-founders of the Sierra Club in 1892), and in 1897 Outing magazine noted women participating in a Yosemite fishing trip without their fathers, brothers, or husbands. Sportswomen sought to feminize wilderness adventures by introducing inoffensive “tramping” clothes (woolen pants under an ankle-length denim skirt that the wearer could pin up, “washer-woman style,” on hilly terrain) and, after the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, by establishing women-only campgrounds at national parks.

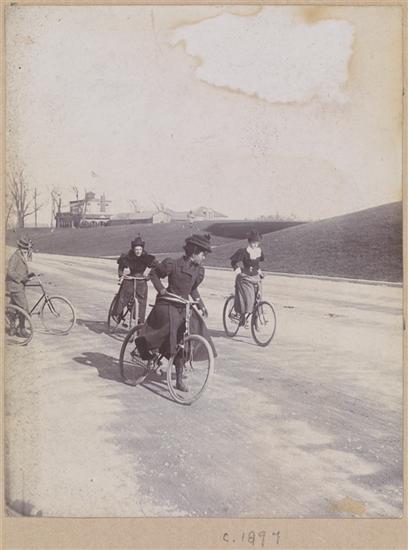

Under their skirts, these women are wearing a version of the athletic bloomer, which made riding a bike manageable in 1897. Fashion magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and The Delineator soon gave cycling costumes their stamp of approval. (Museum of the City of New York)

A bicycle craze swept America in the 1890s, prompted by the invention of the safety bicycle, which was lighter, easier to use, and less expensive than the High Wheeler it replaced. The safety bicycle’s evenly sized wheels placed the rider’s feet closer to the ground, facilitating a quicker stop, and its price tag made cycling affordable for Americans of all classes, unlike equestrian sports. This new vehicle afforded women more freedom than ever before, both as a means of transportation and as a catalyst for clothing reform. Women could not wait to start riding bikes, but they needed an alternative to long Victorian skirts to operate a bicycle safely. The bloomer made that possible. Clothing reformer Amelia Bloomer had women’s health and comfort in mind when she advocated less restrictive garments for women, but she did not invent the item that bears her name. In 1851, after her friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton began wearing “Turkish” ankle pantalettes, Amelia Bloomer also began wearing and promoting them in her temperance periodical The Lily. From that point on, the public and the press christened the pantalettes “bloomers,” and the name stuck. At the onset of the cycling craze, the widespread appeal of the athletic bloomer—wide-legged culottes that came to the knee—paved the way for the gradual acceptance of trousers as a standard garment for women.