I’m a dedicated armchair traveler. I especially like traveling by armchair for trips to Antarctic ice sheets where temperatures sink to 60 below zero, where night (in June, July, and August) lasts 24/7, where at any moment a crevasse in the ice and snow can open its big mouth and eat you. My current tour guide is Admiral Richard E. Byrd, speaking in his book Alone, written in the 1930s. Whether this American explorer was a hero or an egomaniacal publicity hound is debated. I don’t know the answer, but I do know that Alone is a deeply absorbing journey to a land more foreign to most of us than the Moon, which, after all, we can look up and see.

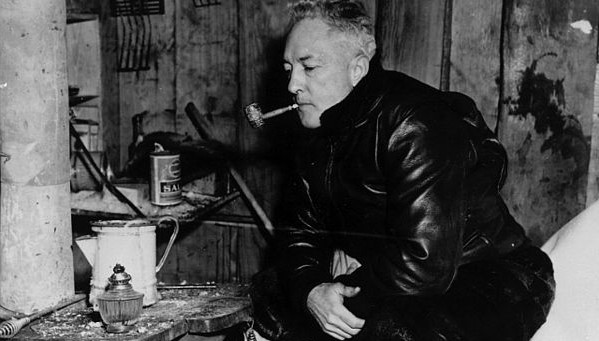

In the winter of 1934 Byrd lived alone in a hut on the Ross Ice Shelf, 100 impassable miles from good talk or any talk, 100 miles from help. One hundred miles that is, from Little America, where the men he commanded had dug in for the Antarctic winter. In his regular life Byrd lived the typical whirlwind of the explorer of his day. It was a life of banquets, ticker-tape parades, and speeches; a life of socializing and phoning and fundraising, all toward gathering support for the next venture. Byrd undertook his solitary sojourn on the Ross Ice Shelf ostensibly to make meteorological observations, but more personally, “to taste peace and quiet and solitude long enough to find out how good they really are.”

You can’t visit Little America now because that part of the Ross Ice Shelf has calved into the Ross Sea. Yet the Ross Ice Shelf is still there. It is still large, as large as France. And thick, in places 3,000 feet thick. It’s twice as thick as the Empire State Building is high. It remains the world’s largest ice shelf. It’s located far to the south of New Zealand, a bit to the west. It’s made by glaciers flowing down Antarctic mountains to the cold Ross Sea. You really must look at a map. I have an old Rand McNally that still shows Little America, situated not far from the Bay of Whales.

The Ross Sea, the world’s most pristine ocean, is inhabited by two species of penguins; by the snow petrel and the Antarctic petrel; by whales both orca and baleen; by Weddell seals (many killed during the exploration era for sled-dog and human food), leopard seals, and crabeater seals; by krill and silverfish, and, most controversially, by the six-foot-long Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni)—industrially fished and expensively sold as “Chilean sea bass.” A movement to protect the Ross Sea from industrial fishing, undertaken by the Last Ocean Charitable Trust, has persuaded at least one grocery chain, Safeway, to pledge to not buy or sell this toothfish under any name. (The closely related Patagonian toothfish [Dissostichus eleginoides], with its wider range, is also sold as “Chilean sea bass.” The Seafood Watch of the Monterey Bay Aquarium advocates eschewing both species, that is, anything called “Chilean sea bass.”)

Byrd meant to live hut-bound through the unbroken night that is the Antarctic winter. But during his weeks of darkness at 60 degrees below zero, his stove began leaking carbon monoxide. Alone devolves into a grim chronicle of his struggle to remain alive.

But it’s also a classic of nature writing. Here is our own sun, strange and cold and red, rising over the Ross Ice Shelf, then called the Barrier:

Each day more light drains from the sky. The storm-blue bulge of darkness pushing out from the South Pole is now nearly overhead at noon. The sun rose this morning at 9:30 o’clock but never really left the horizon. Huge and red and solemn, it rolled like a wheel along the Barrier edge … gradually sinking past it until nothing was left but a blood-red incandescence …

Alone is a great story, but more than that, it brings us nearer to our own planet, to a part of the earth as pristine as we are likely to know, even now, should we care to preserve it.

(For more about the Last Ocean Charitable Trust, go to www.lastocean.co.nz.)