Pakistani-American artist Ambreen Butt studied traditional Indo-Persian miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore. She received her MFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston. Here, Butt discusses some of the works in her exhibition “Mark My Words,” now on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

“Traditional miniature painting is a meticulous process. Everything is made from scratch: paper, brushes, and pigments. Miniature paintings were originally meant to be part of manuscripts, so to make them, you sit on the floor, hold the paper on your lap, and stay there for hours making marks with a small brush. The artists of the Indian subcontinent call the art form mussawari. The name doesn’t necessarily refer to the size of the work but to the special technique involved, the process, the colors, the mark-making on the surface, and the illustrative quality and subtle symbolic meanings in the painting.

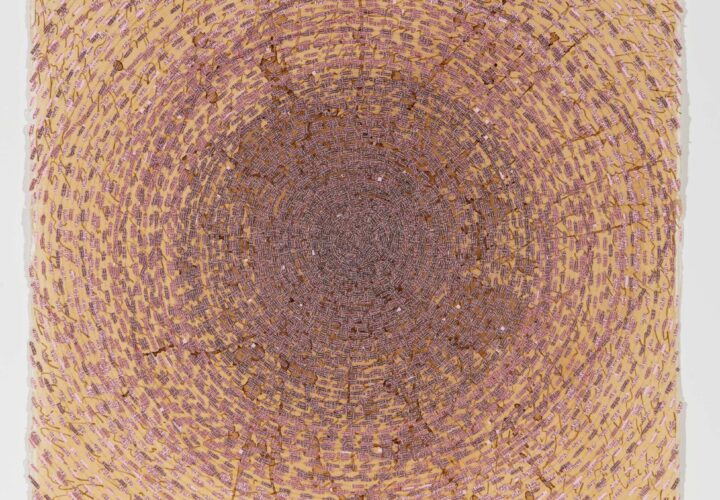

I’m not an artist who makes a lot of work, and I’m fine with that. I prefer quality over quantity. The etchings in my ‘Daughter of the East’ series took several months to produce. One etching is made with six or seven plates that I’ve drawn on. The printing process is done in a way so that each print is layered on top of one another. The same goes for ‘Say My Name’: I make the tea, I stain the paper over and over again, and then I draw on top of it. I was working with the names of victims from drone strikes. I took one name, wrote it over and over again on a piece of paper, and then I shredded the name into small pieces and starting gluing it to the paper. Sometimes the drawing goes underneath the text; sometimes the text is layered, too.

I started the ‘Say My Name’ series for multiple reasons. I am a mother and therefore think about the state of the world in a different way. When I was researching U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan and Afghanistan, it struck me that most of the victims were children who had nothing to do with the conflict. There was one girl, named Ayeesha, who was three years, and who reminded me of my daughter at that age. I started thinking of all these children’s names—they were people at one point, but now they’re nobody. Now nobody knows them, no one knows their stories. I wanted to give a name to the person who had existed: Ayeesha was three, and Shoaib was eight. The drawings will always be titled with the names of the victims. I’m constantly questioning if art can really change the world—I know that my work will only reach the people who see it in a museum, but if it makes them think, then my art has served its purpose.

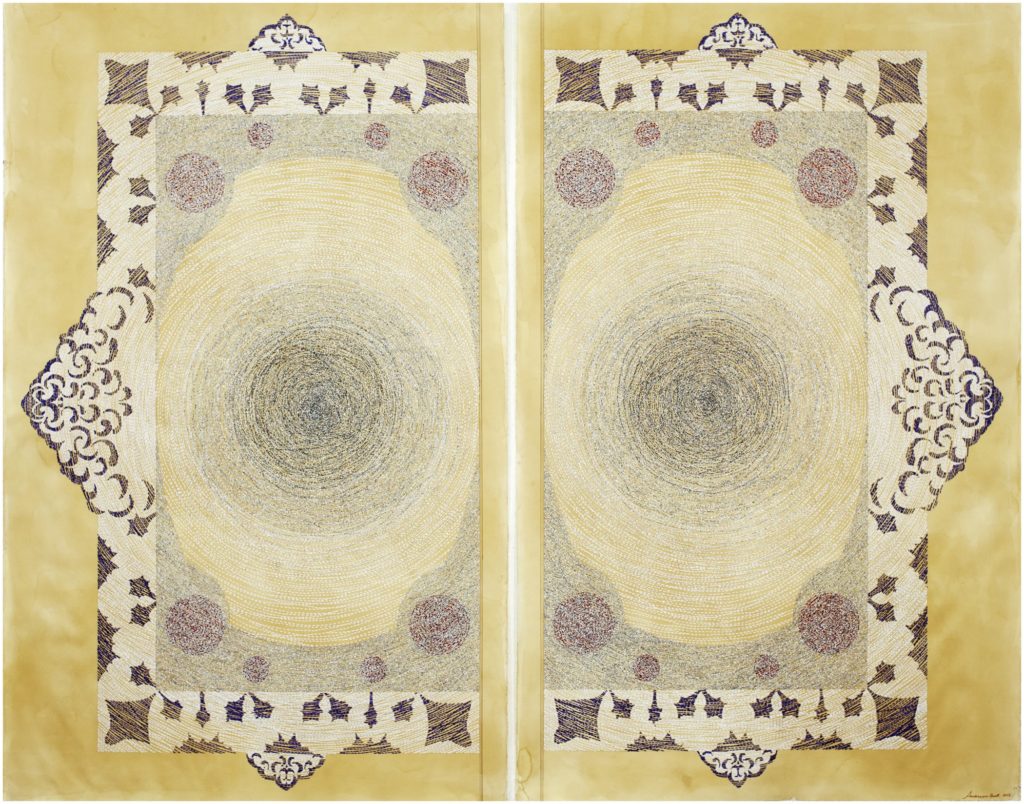

The Pages of Deception dyptich is about the trial of Tarek Mehanna, which happened in Boston while I was living there. One side depicts the closing statement of the prosecutor and the other is the defense. They’ve both been ripped, so you can’t see who is who. Depending on which side of the page you’re on, you decide for yourself what to believe. What struck me about the trial was the defendant’s closing statement. He talked about his childhood growing up in this country and believing in the right of free speech. Based on that, it made me wonder what the counterargument was. How do you decide who is the terrorist and who is not? Who has First Amendment rights? Do they apply to everyone or just to those of a certain privilege? The answers can change, depending on the times you’re living in.”