American Carthage

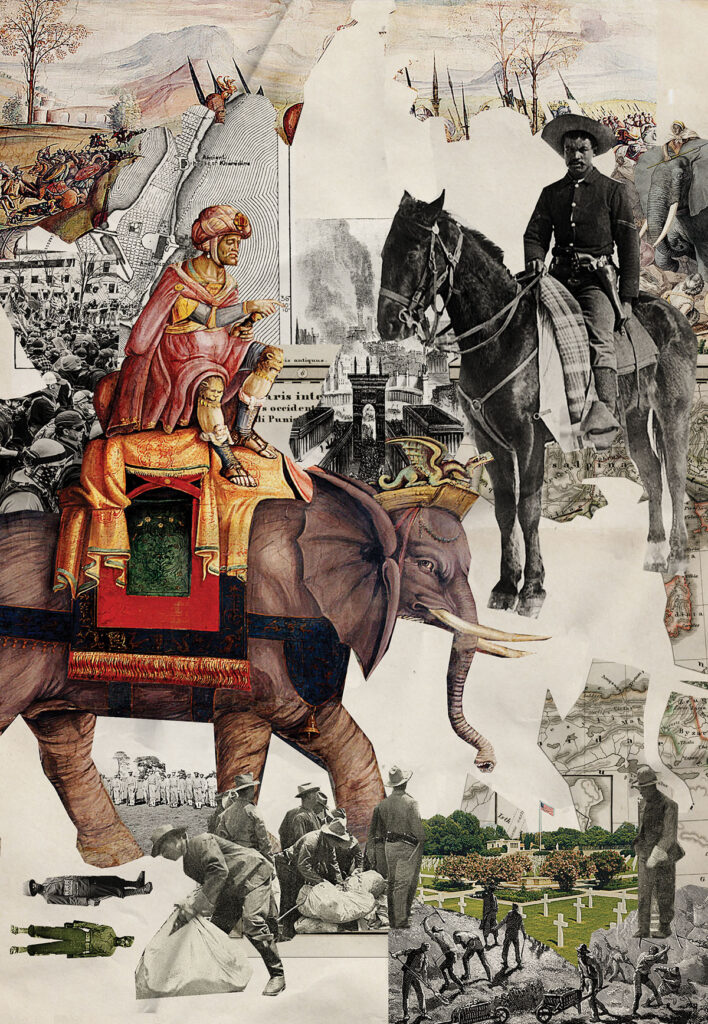

Echoes from the ancient conflicts between Hannibal’s city and Rome continue to reverberate well into the present

Carthage, Tunisia

There are many Americans in Carthage, and most are dead. Buried in the North Africa American Cemetery, on the outskirts of this storied suburb of Tunis, they lie in the same mixture of clay and limestone granules that received the remains of Hannibal’s Carthaginians during the Punic Wars, some 2,000 years ago. Unlike the Romans (rivals to the ancient Carthaginians) and the French (whose conquest of Tunisia began in 1881), we Americans didn’t take this parcel of Africa by force. It was given to us by the French after World War II as a resting place for our military dead. But in 1956, before the cemetery could be completed, French colonial rule ended and there was some question as to whether the new Tunisian regime would honor the bequest of the former colonizer. After some hesitation, it decided that America could still have the land—but only as a gift of the Tunisian people. We were given the land twice.

Today, the cemetery lawn looks as if it had been picked up from a Carolina golf course and laid down on the dry, beige ground like a rug—the unlikely green rendered brighter by the whiteness of the marble crosses that pin it in place. Like an artifact on display in a museum, the cemetery feels finished. Nothing more will happen here, nothing to disturb the sleep of the dead apart from the soft scrapings of landscapers and visitors’ footsteps made heavy by patriotism or the heat. The Latin crosses (and some Stars of David) are hugged tightly from below by Americans who will neither be moved nor joined by anyone else. If ever a place was permanently possessed, this is it.

Of the soldier in Plot F, Row 8, Grave 14, the official record indicates his name, state of origin, rank, unit, and date of death. The unit was the all-Black 92nd Infantry, nicknamed the Buffalo Soldiers Division, so it can be assumed that the surname, Williams, can be traced to the owner of an enslaved ancestor. The U.S. Army considered Black soldiers inferior and did not allow them to fight alongside their white counterparts. In the North African campaign, Black soldiers served in support roles only, but that changed when the invasion of Italy began. The Buffalo Soldiers were now given the privilege of fighting, although not side by side with white soldiers. Williams would not be side by side with them until he was laid to rest, destined to spend eternity in the place where Hannibal was born.

Williams died in a modern Punic War. The Nazis made a point of likening themselves to the heroic Romans and associating the business-oriented, money-grubbing Americans with the sharp-dealing, mercantile Carthaginians. Buried alongside Williams are soldiers who served in Tunisia under General George S. Patton in 1943. Patton believed in reincarnation, and he claimed to have fought near Carthage in ancient times. The following verse is his:

So as through a glass and darkly

The age long strife I see

Where I fought in many guises

Many names, but always me.

Fellow believers have judged him to be the reincarnation of Hannibal. Indeed, Patton bears an uncanny resemblance to an ancient bust said to be of Hannibal. Others contend that although the bust may have been carved to honor the Carthaginian general, its likeness is that of a generic hero. A more accurate portrait, they say, can be found on a coin minted in 217 BCE in Etruria by people anticipating that Hannibal would invade Italy and liberate them from Rome. On the obverse of this coin is the head of a Black African and on the reverse an Indian elephant, presumably Hannibal’s famous war elephant, Surus. From this, some scholars say that Hannibal was Black. Patton did say he fought in many guises.

Along the wall of the North Africa American Cemetery stand three stone statues of women dressed in classical garb. Their names are recollection, honor, and memory, and they are here to help visitors like me organize our feelings. In Roman fashion, recollection holds an open book on which is engraved pro patria, and honor prepares to bestow a wreath of laurel. memory stands with her eyes closed in contemplation—as if to prevent external input distracting her from visualizing the past. But what is memory visualizing that is neither the sacrifice of these soldiers nor their reward? What they looked like, perhaps. The color of their skin. Who they were. For the citizen soldiers of Rome who battled Carthage, only recollection and honor would have mattered. The individualistic culture of America required the additional company of memory.

By now, those who knew Williams are themselves most likely gone. If a person is the product of interactions with others, then so long as those interactions are remembered, that person has presence. There are 240 graves of unknown soldiers at the cemetery, but really, nearly all of the 2,841 buried here are unknown. The official record exists, but what sort of presence is that? memory stands, eyes shut, near Williams’s grave, but with the story of his life long forgotten, she sleeps at her post.

It’s not only the allegorical nature of the statues that interests me. I’m also struck by their style, the ancient made modern. Each figure, sleek as the fuselage of a World War II bomber, is economical in its purpose, as if designed by machine. Much later I discover that it was the sculptor Henry Kreis of Essex, Connecticut, who created them. That discovery took me aback, as Essex is my hometown. The coincidence entered the realm of the surreal when I learned exactly where Kreis had lived and worked. It’s where I live and work. From my window I see his studio, as through a glass and darkly.

What is Carthage to me? The name fires my imagination. A history with burning bookends. The city’s founder, Dido, abandoned by the founder of Rome, throws herself on the pyre. Six and a half centuries later, as Carthage burns, the wife of its leader jumps into the conflagration to deny the conquering Romans the satisfaction. And in between, Hannibal stares up at the cold, seemingly impenetrable Alps and thunders, “I shall find a way or make one!” Then, Hannibal ad portas (“Hannibal at the gates”) and fear in the heart of fearless Rome. But in these Punic Wars, mercantile Carthage, which measures success in silver and gold, faces a martial foe that cares only for victory. Carthage deserves to burn, the Romans say. A city so cruel that it sacrifices its children to the fire of Moloch. And who is Moloch? “Moloch whose blood is running money!” shouts Allen Ginsberg in Howl, with the American factory system in mind. “Abominable sacrileges,” judges Gustave Flaubert in his novel Salammbô, set in the Punic city. Repelled, too, by the materialism of the Carthaginians, Flaubert nevertheless makes me question whether I would not be happy to feast in their gardens with my “diamond-covered fingers wandering over the dishes” and my gaze fixed on the half-naked priestess “kindled at the gleaming of naked swords.” No! demands Cato, that old dry Roman who takes no pleasure in anything but his pride. Delenda est Carthago! he declares on the floor of the Roman Senate, just before the start of the Third Punic War. Carthage must be destroyed. And yet, is not my own country as much Carthage as Rome?

It’s a short walk from the American cemetery to what’s left of the Punic city. The excavated remains are situated near the top of a large hill—known as the Byrsa—sloping down to the Mediterranean. Mare nostrum (our sea), the conquering Romans called it. The Carthaginians (who originated from Tyre) called it the “Syrian sea.” The struggle we know as the Punic Wars reflects the Roman view; had the Carthaginians been victorious, the conflict would be known as the Roman Wars. Names connect us to our heritage, but connections change.

In the heyday of Punic Carthage, the Byrsa boasted multistory townhouses containing statues and objets d’art from around the Syrian sea, mosaics of colored stone, embroidered tunics dyed in vivid reds and blue-violets, Egyptian linens, amphoras of Rhodian wine, perfume bottles of blue glass striped with yellow, necklaces of gold, and bronze mirrors large and small, multiplying through reflection the fruits of successful commerce. Today it’s as if the top half of the city has been sliced off, the contents blown across the sea, and the bottom half crushed by a giant foot. More rubble than ruin, the traumatized walls show little interest in rebuilding. Some stones still bear the traces of red and black, the result of fire and smoke from when the Romans burned the city. My guide picks up a blackened pebble and places it in my hand. I clutch it tight, imagining the conflagration. First to explode in flames are the linens and clothes, and then, after the wooden beams supporting roofs and brick walls catch fire, the buildings collapse. The guide points toward an acacia tree (a symbol of immortality) where a skeleton was discovered together with a small hoard of coins. A Carthaginian trying to make his escape from the Romans had been crushed by a falling wall, and for two millennia, coins and bones lay hidden, intermingled beneath the debris. I find coins and bones an unsettling mixture, as they point in opposite directions. Unlike bones, coins speak to some future purpose, and I imagine the desperate Carthaginian clutching his hoard as a talisman. It did not save him. Bones mixed with coins—that’s ancient Carthage.

I’m still clutching my blackened pebble, my own fragment of ancient Carthage, as if it had talismanic power. Kicked around over the centuries, it has no archaeological value, but still, the legacy of looting is such that I cannot keep it. Not wishing to offend my guide, I drop it when she’s not looking. One day it may be someone else’s memento, or ground underfoot.

Carthage, New Mexico

Of the dozen towns in America named Carthage, the one in New Mexico bears the closest physical resemblance to the remains on the Byrsa. At the turn of the 20th century, the coal-mining town of Carthage had 1,000 residents; by the 1960s it was a ghost town, and in 1999 its buildings were bulldozed as part of a desert restoration project. Yellowish stones shaped by miners are composed of much the same limestone material as the stones on the Byrsa—as if ancient Carthage were a blood ancestor. In Tunisia, the stones once brutalized by the Romans are now being protected from the soil. Here in New Mexico, the ground has been encouraged to swallow up the remains. The stones of this American Carthage whisper almost nothing of its past, choked by rising earth.

I’m here on a trek across the country, visiting towns named Carthage. I’m interested in why the name was chosen and the significance it has for residents. Here there is no one to ask. What little is to be learned I find in old newspaper articles, the distant recollections of two women, and a letter from the archive of the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology. The letter mentions in passing a mine dug in 1866 by a “detail of colored soldiers from old Fort Craig.” It was the state’s first coal mine, and the coal was used to heat the fort. The site was given the name Carthage by an officer at the fort. The letter doesn’t indicate why, but it’s no coincidence that the African name was chosen because only Black soldiers were there. It was Army policy that Black soldiers be assigned the most laborious of tasks (as they were not allowed to fight), and no task was more laborious than digging for coal. Just a year later, though, when the Apache went on a rampage, all soldiers were needed for fighting. So officers at Fort Craig wrote to Washington asking that the Army change its policy. When it did, the Black soldiers at Carthage exchanged shovels for rifles. They were the first Buffalo Soldiers, so named by the Apache because of their dark, kinky hair. Now these Black men saw their lives go from laborious to dangerous—something Billy D. Williams, one of the last Buffalo Soldiers, would later know all too well.

Buffalo Soldiers killed in the first years of fighting (one was axed in the back) were buried outside Fort Craig. The fort was abandoned in 1885, and its cemetery was ignored until the 1970s, when an amateur historian, Dee Brecheisen, seeing no interest on the part of professional archaeologists, began excavating on his own. A Vietnam veteran, Brecheisen lived up to his handle “gravedigger,” smashing through coffins in search of old buttons and coins. Delighted to come upon the remains of a Buffalo Soldier, he kept the skull as a trophy, pieces of brown flesh and black curly hair still attached. For years he displayed it proudly in his home.

The story—scandalous now—is of a piece with the history of archaeology and collecting. Even Brecheisen’s untroubled display of nonwhite remains is consistent with the practices of many museums—all part of the legacy of colonialism and white supremacy. After some research, Brecheisen eventually determined that the skull had belonged to Tom Smith. Now that the head had a name, did Brecheisen, one wonders, feel differently about displaying it?

Graves from ancient Carthage were looted, too—part of the antiquities trade—but enough survived so that archaeologists could introduce funerary objects into the story of Rome’s rival. It is literary sources, however, especially Polybius and Livy, that have made the most profound impression. Rome’s destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE brought the fighting to an end, but in the Western imagination, the Punic Wars were just beginning. Much as American children used to play cowboys and Indians, so young Napoleon Bonaparte played Romans and Carthaginians. Later, as a self-styled Roman emperor, Napoleon played the game on a grand and deadly scale. The French and the English had long likened their rivalry to that of Rome and Carthage. French revolutionaries saw themselves as new and “virtuous” Romans (of the Republic) and professed to despise the greed of the seafaring merchants of the “modern Carthage” across the channel. In 1798, when Paris resounded with calls for the destruction of the English Carthage, the London-based Morning Chronicle fired back nonchalantly:

The haughty Chiefs of Gaul may roar

“Delenda est Carthago!”

But if their rafts approach our shore,

We’ll give them the—Lumbago.

In England, the Punic parallel was taken more or less in stride. Unlike the French, who would never have named one of their new cities after Carthage, the English saw merit (and themselves) in Rome’s ancient rival.

America’s founding fathers were impressed by both ancient republics. John Adams rejected the traditional Rome (virtue)–Carthage (avarice) dichotomy. “If the absence of avarice is necessary to republican virtue,” he writes, “can you find any age or country in which republican virtue has existed?” Dismissing the old maxim that “commerce corrupts manners,” Adams points to the Carthaginians, whose “national character was military, as well as commercial,” adding that “although they were avaricious, they were not effeminate.” Americans were building a commercial republic, and for that there were few models, none better, in the eyes of Adams (as well as James Madison and others) than the ancient republic on the northern coast of Africa.

The Romans (who looked down on commerce and preferred to gain wealth by taking it from others) were said to have hated Carthage so much that after they destroyed it, they sowed its fields with salt. Nothing must grow there again. That hatred, rooted in fear of Hannibal at the door, was real; the sowing of the salt was not. Carthages did grow. There, in North Africa—and again and again in America.

As a place name, Carthage is first and foremost a marker. Maine’s Carthage was originally called Plantation #4. But the lumberjacks there wanted a name more meaningful than a term in a series. When the right to name the town was auctioned off, a schoolteacher who “delighted in the exploits of the Romans and the Carthaginians” paid two dollars for the right to name it Carthage. Just like that, the lumberjacks became Carthaginians. In Tennessee and New York, classically minded lawyers named settlements on navigable rivers after seafaring Carthage. Hilltop settlements in North Carolina and Missouri are surmised to have been named Carthage because of the Byrsa or the Alps. Carthages in Indiana, Illinois, Mississippi, Texas, and North Dakota were named in honor of settlers from other Carthages in the East. In Arkansas, Ohio, and New Mexico, Carthages were likely named with Black residents in mind.

At first, American leaders looked to ancient republics to back them up in their political experiment. Hence we have the Capitol and the Senate and the Roman eagle as our national emblem. And we have towns named Carthage. But over time, the importance of the classical world, tied as it was to republicanism and elitism, diminished in the face of anti-elitist and anti-intellectual forces—egalitarianism, democracy, utilitarianism, materialism, ferocious piety—the very forces, in fact, that scholars have associated with the decline of ancient Carthage. In America, the idea of Carthage faded in significance as the country became more and more Carthaginian.

Only in Carthage, Missouri, is the name foregrounded, with the town hall exhibiting Punic artifacts and paintings that draw parallels between the town’s history and that of its North African counterpart. Other American Carthages don’t draw much attention to the name. Doubtless the growth of racism and anti-Semitism lessened the name’s appeal. Carthage had been founded by Phoenicians, a Semitic people, and it was a short step (for some) to think of them as the “Jews of Antiquity”: clever traders, untrustworthy, and cruel. That, together with the African connection, associated Carthage in some minds with two degraded peoples. But when I asked residents of towns named Carthage what they thought of the namesake, the link to antiquity seemed tenuous at best. I often heard: “It was a Greek city, wasn’t it?”

Many place names originate as living units of speech, coined by distant ancestors as descriptions of a location’s appearance, situation, use, and ownership, or some other association. But over time, they become mere labels, no longer possessing a clear linguistic meaning. As here in New Mexico. On the rare occasions that folks in the region refer to the old mining town, they often call it Cartridge. The name fits, for along the path to the site are spent shotgun cartridges, weathered and half buried in the dirt.

In New Mexico’s Carthage, only the cemetery lives on, and that is moribund. Of the dozens of gravestones there, the least weathered is that of Evelyn Fite, who died at the age of 98. When I spoke to her, some eight years before her death, she said she was looking forward to resting in the Carthage Cemetery alongside her departed husband, though she lamented its deplorable condition. There is no real boundary between the gravesites and the desert, making them hard to see from the road. Being scarcely visible was not Evelyn’s style. As we made plans for my visit, she assured me on the phone that her bright blue house in the hills of Socorro would be easy to find, and it was. The blue was loved by the Indians, she said, a welcome change from the beige of the desert. She smiled when I told her I’d seen doors in Carthage, Tunisia, the very same color. I mentioned that in the 1780s Thomas Jefferson had been interested in the theory that the Indians of America descended from ancient Carthaginian explorers. Evelyn knew little about antiquity but was quite familiar with the old mining town of Carthage because she used to own it. It was situated on her ranch, and occasionally she poked around the ruins.

Evelyn made arrangements for me to visit the site, and as we said our goodbyes, she showed me a small bronze object, shaped like a miniature amphora. It was an antique miner’s cap lamp she had found there years before. She placed it in the palm of my hand, as if to give me insight into the town’s past. The oil wick was tiny, so the flame must have been slight—enough to see just inches in the pitch black of the underground.

Even the slightest flame, though, would be enough to ignite a buildup of methane gas. In 1907 an explosion at Carthage killed nine miners. “The body of one miner who was coming out of the mouth of the mine when the explosion occurred was shot a hundred yards into the air as if from the mouth of a cannon,” reported the Socorro Chieftain. The town never recovered from the catastrophe. Thirty-seven years later, its abandoned buildings were rocked by an incomparably greater explosion nearby: the detonation of the first atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test. Florencia Jaramillo, at the time a young girl who lived up the hill from Carthage, remembers windows in her home breaking.

To see the little that is left of the old mining town requires a long walk on a tortured dirt path through the desert. The path winds slowly downward through tight draws and arroyos, between outcroppings and mounds that become higher and higher as the path descends. Florencia used to make this trek as a child. She skipped and sang all the way, she told me. But not because she was happy. She did it to keep her spirits up. She was scared by the descent into Carthage, the dark openings beckoning her deep into the earth. Her family members were ranchers, and she was used to the spaciousness of the range. Being in Carthage made her feel trapped.

This land is part of the Rio Grande depression, and geologic faults together with erosion are responsible for the jumble of mounds. Between greasewood bushes, clumps of tall, seemingly lifeless grass stand at attention in the company of yucca and prickly pear cactus. The yucca’s sharp-pointed leaves appear like raised swords, and the needled oval pads of the prickly pear suggest shields with arrows embedded in them. Prickly pears are common in Tunisia, too, but they weren’t there in ancient times. They’re colonialist invaders from across the sea. From American deserts just like this one.

Eons ago, all this was beneath the sea, and among the rocks, fossils can be found. Dig down and there’s fossil fuel. Ancient plant matter, entombed in mud and protected from the air and decay, became something else entirely. Miners came to Carthage to draw energy from the ancient past.

The mines supplying coal to Fort Craig were taken over by the San Pedro Coal and Coke Company. The company built 50 residences at Carthage—numbered one to 50—all 50 feet apart and exactly alike, “so that,” The Bullion reported, “if one of the residents should happen to stay out late with the boys and partake a little too much of the flowing bowl, he would have some trouble finding the proper keyhole.” A Santa Fe newspaperman passing through in April 1888 wrote,

One can hardly go into ecstasies regarding the beauties of Carthage as a residence location. Below the hoisting works a long row of about twenty one-story houses faces the railroad with a street between. Above the works a similar row of two-story houses is as monotonous as to architecture and desolate surroundings as a thousand cross ties in the railway track. Not a tree or shrub, a leaf or flower enlivens or beautifies the village. It is a strictly utilitarian enterprise.

Utilitarian was what the company wanted, but the miners wanted something more. They wanted community. They wanted a school for their children. The company—in classically Carthaginian fashion—acquiesced only when the miners agreed to pay for it themselves.

One of America’s most iconic rags-to-riches stories began in Carthage. A young Conrad Hilton used to ride the train to Carthage, delivering food to miners. It’s said of the youngster that he used to go barefoot, as if this proved his mean beginnings. Hilton, of course, went on to make an enormous fortune in the hospitality business. A little research shows that although Conrad was indeed a delivery boy, he was delivering food to workers at a mine owned by his father. Young Hilton may at times have been barefoot, but he was never in rags.

Miners were. An old photograph with the caption “Carthage” shows them in sooty clothes, wearing cap lamps like Evelyn’s and leaning against a lode car. They look grim, as if they know the photo is not being taken for their benefit. Coal mining was a dirty business, but it was a profitable one for Conrad’s father, Augustus. Named for the Roman emperor who redeveloped Carthage a century after its destruction, he sold the mine in 1904 for $110,000, the equivalent of more than $4 million today.

Not everyone in Carthage prospered. The railroad was its lifeline, bringing in food and water and carrying out coal. When operations were no longer profitable, the railroad company pulled out, dooming the town. Left behind was a single lode car, today rusting in a pile of debris. Some see a direct connection between American railcars and ancient chariots, based on the idea that European wagons (precursors of trams and then trains) were designed for rutted Roman roads. Both chariot and railcar are the width of a pair of horses, and I imagine the rusting lode car as distant kin to the chariot that carried the Roman general Scipio to the gates of Carthage. I sense that antiquity persists in hidden ways, like veins of coal in the underground.

In 1886, The Bullion published an article titled “carthage—The New Mexico Town of that Name. Without any Marius to Weep Over its Ruins, because it has No Ruins, only Coal Mines.” That was then. Now, two millennia since the great Roman general and consul likened his own downfall to that of Carthage, I sit Marius-like beside the ruins of a chimney in the New Mexico desert. I’m quite alone. If bitten by a rattlesnake (and Evelyn warned me there were many in these rocks), I might not make it out. A suitable fate for one who feels himself the sole citizen of a city that no longer exists.

American Carthage

Evelyn was surprised when I mentioned her town name’s connection to Africa. Not that she had given the matter much thought. At the turn of the century, more than 100 African Americans lived in nearby Socorro, so it is not unlikely that at least a few of the Carthage miners were Black. I was unable to determine whether any were buried in the Carthage Cemetery.

In many American towns (including some named Carthage), separate cemeteries exist for Black and white. In Tunisia, too. Most Tunisians regard themselves as Arab and “white”; some 15 percent are considered “Black,” or “African.” Black skin is associated in Tunisia with slaves or servants, and those who have it are discriminated against in the usual unhappy ways. In 2023, fears expressed by Tunisia’s president that sub-Saharan migration was making the country too “African” unleashed waves of violence against migrants and Tunisians with dark skin.

Racism has been a factor in perceptions of ancient Carthage as well. Martin Bernal in Black Athena (1987) asserted that the West’s cherished insistence on seeing its own childhood in ancient Greece was a racist illusion. Scholarship had ignored what the Greeks themselves knew well: that their culture owed much to the Phoenicians and Egyptians. Classicists imagined the ancestry of the West to be as white as the Greek sculptures they found so graceful. Traces of colored paint on ancient sculptures unearthed from the ground were removed, just as the dirt was. Athena, goddess of wisdom, had to spring from the head of Aryan Zeus, not from the loins of darkish people.

How dark were the Carthaginians? Over the centuries, the founding Phoenicians mixed with Indigenous North Africans, so it’s safe to say that Hannibal’s Carthaginians came in different hues. But some Americans have insisted on “black or white” answers. James Walker Hood in his history One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (1895) called ancient Carthage “a negro republic” and credited Hannibal with having “contributed to the honor of the negro race.” In 1981, Anheuser-Busch commissioned a painting of Hannibal from African-American artist Charles Lilly, who depicted the great Carthaginian as Black. The portrait, which was reproduced on posters and calendars, was part of the company’s marketing campaign in African-American communities. The idea was to associate the King of Beers with the great Kings of Africa, like Hannibal. Afrocentrists continue to debate along these lines. In his 1995 book, Hannibal the Conqueror, Charles Hinton describes Hannibal as “a muscular black man” and (in an accompanying video) states that “the brother almost conquered the Roman empire, did he have soul?” Earlier plans for a movie about Hannibal were derailed because of concerns about the actor’s color, but now Netflix has flexed its muscles and chosen Denzel Washington for the role. Hollywood’s next Hannibal ad portas will be Black.

Sure to object will be America’s would-be Romans—neo-Nazis and white supremacists intent on denying any greatness to the Black race. The online forum “Jews and Afrocentrism,” on the white nationalist website Stormfront, features a figure named Scipio Americanus who insists that Carthage was “a truly white culture” and that the Carthaginians employed “a strict caste system with Whites at the top and the truly black Numidians as slave labor or mercenary soldiers.” “White” means of non-Jewish European descent; and it’s important to white supremacists that southern Europeans (like the Romans) be viewed as unproblematically white. That many southern Europeans have dark complexions is not a complicating notion for them; they blame a Jewish conspiracy to fatally undermine the category of whiteness in order to keep “white brothers” divided. In this polemical Punic War, appeals to brotherhood—be it soulful or white—are committedly confused.

In Europe, members of the Eurasian movement—which arose in the Soviet Union during the early 20th century—accuse America of being the new Carthage: using its global economic network to restrict Russia (which ought to be the dominant land empire) just as ancient Carthage once used its seafaring trading network to restrict Rome (and England used its sea power to restrict Germany in the first half of the 20th century). This latest Punic analogy can be traced to Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin, who at times has had Vladimir Putin’s ear. Dugin predicts the end of “American Carthage” as well as the Western consensus (liberalism) that supports it. Far-right folks in America see merit in Dugin, though they’ve had to overlook his indifference to race. That they find quite un-American.

An article titled “America is the New Carthage and it must be Destroyed” (on the alt-right site Amerika) associates Carthage with individualism (seen as pure selfishness) and equality (described as sacrificing children to Moloch). “Carthago lives on in every corrupt, amoral and incompetent political factotum who claims to rule on behalf of the people,” writes the author, who concludes that “Carthago is just about every city in the United States of Amerika.” What’s needed is a new Rome characterized by strong nationalism and social order through caste and hierarchy. Presumably those who push for such a hierarchy do not imagine themselves at the bottom.

In 1790, the Count of Estaing, a French admiral who had aided the American Revolution, advised George Washington that under his presidency, the new republic must be “tout à la fois Rome & Carthage”—that is, an amalgam of the two ancient cities. Presumably the count meant an America in which both Jeffersonians, promoting civic virtue, and Hamiltonians, promoting commercial success, would feel at home. A more cynical view is that for America to be what Rome and Carthage once were—rivals unto death—it is to be torn apart: torn between virtue and avarice, patriotism and commerce, Western civilization and its African “other.”

Jefferson and Hamilton were fierce rivals, but Washington kept them both as close advisers—as if seeking to make the Rome-Carthage tension productive in the service of the young nation. Two centuries later, his republic was tout à la fois the greatest military and economic power in the world. The racial tension Washington could resolve only at a personal level. A slaveowner, he arranged for his slaves to be freed upon his death. Today, nine out of 10 Americans named Washington are Black, including the Hannibal of Netflix.

The great obelisk built to honor our first president, the Washington Monument, is graced by 194 memorial stones from around the country and the world. One of these stones, consisting of red and white marble, arrived at the monument in 1855 but was misplaced during construction. It was found a century later, and in 2000, on the anniversary of George Washington’s birth, it became the last stone to be inserted into the monument. The last word, so to speak. The stone, chiseled from an ancient temple across the Atlantic, bears a message in colored stone inlay, consisting of an image and a single word. The image (a horse) is the insignia of a famous ancient city, and the name beneath is Carthago.

The obelisk, a form not uncommon in ancient Carthage, and the neoclassical Capitol building, which was built by enslaved Americans, stand at opposite ends of the National Mall, facing each other like rivals. Between them is the long lawn on which Americans can gather and reflect on the nature of their country. Few who do this today think of Montesquieu, as the founding fathers did. The French philosophe wrote,

True is it that when a democracy is founded on commerce, private people may acquire vast riches without a corruption of morals. This is because the spirit of commerce is naturally attended with that of frugality, economy, moderation, labor, prudence, tranquility, order, and rule. So long as this spirit subsists, the riches it produces have no bad effect. The mischief is, when excessive wealth destroys the spirit of commerce, then it is that the inconveniences of inequality begin to be felt.

Chief among those inconveniences is divisiveness, which is what Montesquieu thought undid the Carthaginians. The rich became lazy and the poor resentful, making the Carthaginians less unified than the Romans and less constant in the face of adversity.

To track the name Carthage in America is to follow the changing heart of the country. More than a century has passed since a new American town was named Carthage. Today the name may resonate among polemicists, but it means little to most Americans—even those residing in towns called Carthage. It’s like a peculiar headstone noticed only in passing by mourners on their way to another grave. And yet, that stone, worn and partially sunken, still stands—waiting for honor, recollection, and memory.