American Mandarins

David Halberstam’s title The Best and the Brightest was steeped in irony. Did these presidential advisers earn it?

On September 1, 2022, a classic of American journalism and politics will be 50 years old: The Best and the Brightest, by the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and author David Halberstam. Still in print, it explored in unprecedented detail and memorable style “why men who were said to be the ablest to serve in government in this century had been the architects” of what the author considered “the worst tragedy since the Civil War.” That tragedy was, of course, Vietnam. The current edition includes a foreword by the late Senator John McCain, whose harrowing experiences as a prisoner of war gave him perspective on the decisions that brought so much Vietnamese and American suffering.

For many commentators, the anniversary will be the occasion for renewed debate about what went wrong in Vietnam—in the light of not only the Iraq War and its aftermath but also the traumatic exit of Americans and some of their local allies after the unexpectedly swift fall of Kabul last year. Very few observers still believe that further escalation and commitment of resources could have preserved an independent South Vietnam. And although some others suggest that friendly persuasion (as championed by Edward Lansdale, celebrated in the military writer Max Boot’s biography The Road Not Taken) might have turned the tide, there has been no broadly based revisionism since Halberstam’s exposure of the elite political advisers to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson whose hubris is captured in his book’s title. The roles of individuals are still debated, but as the title of a book by former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara put it, this and much else about the Vietnam war constitutes an “argument without end.”

Beyond assigning responsibility for U.S. policy in Vietnam, Halberstam’s book explores another theme proclaimed by its title, which is the larger role of the American mandarin, a career adviser to presidents and other high officials who serves as a political appointee rather than as a civil servant. Even those who have never read the book know the phrase the best and the brightest as a reference to a position in government that is unique in the world. Halberstam mistakenly believed, at least initially, that people took his title literally. And John McCain’s foreword to the Modern Library edition reads the title as a genuine tribute to gifted patriots, despite the taint of hubris. But as one critical defender of meritocracy, the British writer Adrian Wooldridge, puts it in his book The Aristocracy of Talent, “Thanks to Halberstam, the phrase ‘the best and the brightest’ now comes with an exasperated sneer.” That is quite a comedown from the 19th-century hymn about the Star of Bethlehem that may have inspired the title.

Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in 1967 (National Archives And Records Administration)

When McGeorge Bundy died in 1996—as the charismatically brilliant Harvard professor and popular dean who became national security adviser to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, he played a leading role in Halberstam’s drama—his fellow mandarin the Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called him “the last hurrah of the Northeastern Establishment.” But Schlesinger was only half right. The Establishment never really ended, nor did the role of the mandarin that was a distinctive part of it. Far from liquidating, the mandarinate has continued to flourish in the 21st century, though more in some administrations than in others. It has become more diverse, first by national origin and religion—Schlesinger no doubt had the European Jewish ancestry of Henry Kissinger and Walt Rostow in mind—and then by race and gender.

It has been easy to overlook the continuity of the American mandarins because they have gone by so many names during the past 100 years: the Inquiry, the Brain Trust, the Wise Men, the Kennedy White House Action Intellectuals, the Friends of Bill [Clinton], the Vulcans of the George W. Bush administration, and most recently (in the ironic phrase of Anne-Marie Slaughter, a think tank president and former director of policy planning under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, regarding Barack Obama’s and Joseph Biden’s confidants) the Band of Brothers. That last phrase is a reminder that whatever strides in the direction of diversity have been made in the mandarinate, white males educated in the Northeast continue to dominate.

The word mandarin has no strict definition. It can denote prominent academics, whether or not they are politically active, as in the historian Fritz Ringer’s 1969 study of one professoriate, The Decline of the German Mandarins. It can also refer to those academics who support government programs without necessarily holding political appointments. The linguistics professor Noam Chomsky—himself a mandarin in Ringer’s sense—attacked such liberal colleagues abetting the Vietnam war in his book American Power and the New Mandarins, also in 1969. Mandarins are what logicians call a fuzzy set, or as classical German sociologists like Max Weber and Georg Simmel phrased it, an ideal type.

The United States has thousands of high-level career civil servants like the European mandarins in virtually every government department. A professional society, the Senior Executives Association, counts 7,200 such nonpolitical employees. The best-known example is Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the chief medical adviser to the president.

What unites the uniquely American mandarins might be called a life template, a sequence of credentials and offices. The senatorial class of the Roman Republic and Empire called its template the cursus honorum, an itinerary of civil and military responsibilities leading ideally to the office of consul. Would-be traditional Chinese mandarins had to pass a grueling test on the classics, in principle open to all. (Even a failed result could be a prestigious qualification for a nongovernment profession.) The American mandarin has a narrower path: one of a handful of private undergraduate programs, ideally a Rhodes Scholarship, a few law schools, an initial civil service or diplomatic appointment, political campaign work, and above all what might be called an anchor career as a law partner, professor, foundation executive, media pundit, or think tank fellow. At this anchor stage the mandarin is available to his or her political party, and sometimes to presidents of the opposing party seeking balance. The mandarin career can lead to appointment as secretary of a major department like State, Defense, or Treasury; Henry Kissinger is the most celebrated mandarin on that path. Occasionally, it points to electoral politics instead, but most mandarins—a prominent exception being Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan—have been happiest behind the scenes and rarely seek elective office.

The mandarin class stems from the American path to world power. When the nation assumed a global role in Asia and the Pacific following victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898, its federal institutions were unprepared. In 1900 the State Department had only 91 Washington-based employees, whereas European capitals employed enough diplomatic corps members to fill majestic headquarters. Europe had centuries of experience in educating a cadre of high-level civil servants, its own mandarins. The University of Göttingen was established in the mid-18th century to prepare young men for the law and administration; Emperor Napoleon, impatient with the state of French universities, founded a series of grandes écoles in the early 19th century whose graduates entered public service on a high-level track; English so-called public schools plus Oxford and Cambridge led to careers in a proud senior bureaucratic community that has been called Whitehall Village. (The popular British television series Yes Minister is a satire on the alleged power of ostensibly deferential senior civil servants to obstruct the goals of their nominal political superiors in the cabinet.)

Alexis de Tocqueville, a civil servant himself, thought the absence of a national bureaucracy in the United States more of an asset than a liability. At the time of his visit in the early 1830s, Jacksonian democracy was on the rise, and with it the spoils system, not curbed until the Pendleton Act of 1883 introduced competitive examinations and employment security for many federal jobs once awarded to partisans. (President James A. Garfield, a Williams College Phi Beta Kappa and classical scholar, was a crusader for civil service reform who paid for that stance during his first year in office, when he was assassinated by a delusional would-be diplomat.) In his 1902 inaugural speech as president of Princeton, Woodrow Wilson called on the university and other institutions to look beyond “mere technical training” and the “neglect of the general” and equip a new generation of “efficient and enlightened men” for a country whose “interests begin to touch the ends of the earth.” College, he declared, is for “the minority who plan, who conceive, who superintend, who mediate between group and group and must see the wide stage as a whole.” The speech, revisiting the theme of an address Wilson had given at Princeton’s 150th anniversary celebration, was reprinted in full in Science magazine. Unhappy with his time teaching at Bryn Mawr College in the 1880s, Wilson ignored the rise of women’s education. The Wilson biographer W. Barksdale Maynard quotes Wilson’s wife on the occasion: “It is enough to frighten a man to death to have people believe in him and expect so much.” The next year, Oxford University inaugurated the Rhodes Scholarships, endowed to create a global network of Anglophile leaders.

Despite his summons to a new cohort of idealistic graduates, Wilson was his own mandarin and employed few of them. His closest adviser was Colonel Edward M. House, a Texas entrepreneur and one-time state kingmaker without a college degree but with social and political skills that complemented Wilson’s high-strung personality. One major exception was the first real American-style mandarin, the journalist and public philosopher Walter Lippmann, who had, like McGeorge Bundy after him, no graduate degree. But like Bundy at Yale, Lippmann at Harvard had been a boy wonder of dazzling analytical gifts that won him the mentorship of older generations in politics and journalism. An important supporter of Wilson’s presidential campaign, Lippmann was even a speechwriter for Wilson while still assistant editor of The New Republic, despite Wilson’s later reputation as the last president who wrote his own speeches. After America’s entry into the Great War, Lippmann was one of a half-dozen brilliant young progressives appointed as assistants to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. (According to his biographer, Ronald Steel, Lippmann was offered the job as a result of writing to Baker for a draft exemption.) During peace negotiations, Lippmann served as secretary of an informal society of noted academics, simply called the Inquiry, tasked with reforming Europe’s borders. Meeting in the exclusive clubs to which many of its members belonged, the Inquiry evolved into one of today’s mandarin pillars—and a prime target of conspiracy theorists—the Council on Foreign Relations. Studies by the Inquiry scholars of the ethnic and political geography of Europe, synthesized by Lippmann, became the basis of eight of the Fourteen Points promulgated by Wilson at Versailles. Lippmann thus helped establish the 20th-century think tank, ad hoc though the Inquiry was.

No doubt influenced by his experience coordinating the research of the Inquiry, Lippmann published 100 years ago what may be his most frequently cited book today, Public Opinion, modifying his former optimism about citizens empowered by a free press. Newspapers and magazines portray events but are ill prepared to analyze causes and recommend policies, he thought. This role should be filled, he believed, by panels of experts to whom citizens would have to defer because of the growing complexity of science and technology. Those specialists would not determine policies themselves but would inform the work of government. The French have a word for distinguished scientific consultants, savants (a term with a very different popular English language meaning today). Implicitly, another class of Wilsonian generalists like Lippmann himself would convey the savants’ conclusions to those in power. A de facto distinction between mandarins and savants persists. Savants develop technologies and write reports; mandarins recommend whether and how their policies should be implemented.

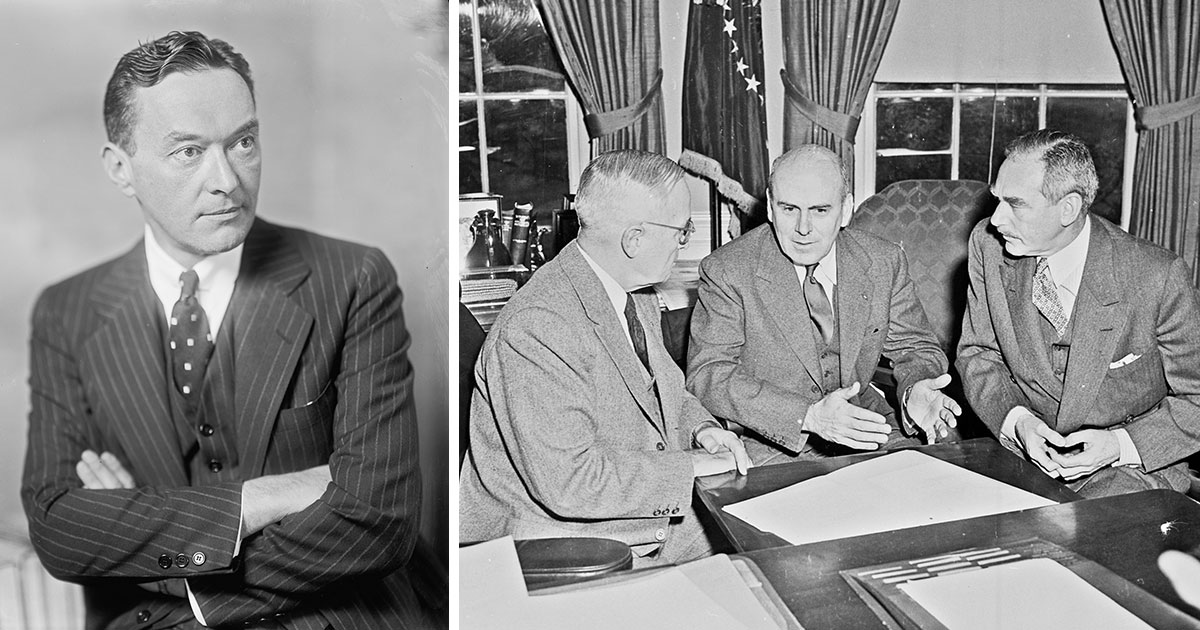

Left: Walter Lippmann in 1905; right: Harry Truman with John J. McCloy and Dean Acheson, January 1950 (Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress; Abbie Rowe/National Archives and Records Administration)

Lippmann was—as the polymath public intellectual Lewis Mumford later described himself—a “professor on things in general.” Verbal agility and flexible omnicompetence became hallmarks of the American mandarin, whether journalist, academic, attorney, or scientist.

After President Wilson’s failure to win American membership in the League of Nations he had championed, the mandarin ideal was largely dormant in the Harding and Coolidge years. Herbert Hoover, despite his prowess as a mining engineer and entrepreneur and his fame relieving hunger during and after the Great War, had not been an academic star at Stanford.

Franklin D. Roosevelt originally impressed Walter Lippmann as a good-looking, affable mediocrity; he had been a C student at Harvard, unlike his cousin Theodore, who was elected to Phi Beta Kappa (though his grades were uneven), and he never wrote an honors thesis. Yet FDR did more than any previous president to institutionalize expert advice by recruiting a number of Columbia professors to join what became known as the Brain Trust. This was the first cadre of academic political and economic lieutenants widely known by name to the public. The early New Deal was a burst of pragmatic initiatives, and such specialists were indispensable if FDR—who once joked that everything he had been taught in his Harvard economics courses was wrong—was to address the greatest financial crisis of the 20th century. The Brain Trust leader, Raymond Moley, had already been an important ally and speechwriter during the campaign. FDR had promised him unlimited direct access, and Washington insiders parodied an old hymn: “Moley, Moley, Moley, Lord God Almighty.”

A pragmatic Ohioan by background, Moley turned against the New Deal when Roosevelt espoused what Moley considered antibusiness legislation; Rexford Tugwell, an ardent supporter of planning and one of the most left-leaning Brain Trusters, was forced out because his views were too extreme. Lawyers now came to the fore among Roosevelt’s advisers. Thomas Gardiner Corcoran (“Tommy the Cork”) and Benjamin V. Cohen had both excelled at Harvard Law School and were mentored by the future justice Felix Frankfurter. One was an extrovert and master negotiator, the other private and rumpled but one of the greatest drafters of legislation in American history.

Under Frankfurter’s influence, Harvard Law School became the premier training ground for mandarins. Nor was its power limited to Old Grotonians like the Roosevelts and the Bundys. John J. McCloy was the son of lower-middle-class parents in Philadelphia. His mother was a hairdresser who mobilized her society clientele to help put her son through prep school, Amherst, and Harvard Law School. Despite an otherwise strong record, he was not one of the top students in Felix Frankfurter’s class. He nevertheless was able to join a succession of elite corporate law firms and made his reputation as an ace international detective, representing Bethlehem Steel in a lawsuit against the German government. The suit’s favorable outcome helped win McCloy an appointment as assistant secretary of War under Henry L. Stimson, for whom he became a problem solver. In Richard H. Rovere’s tongue-in-cheek 1961 essay in The American Scholar on the American Establishment, McCloy appears as the most identifiable chairman. Rovere rattled off the medals: “former United States High Commissioner in Germany; former President of the World Bank; liberal Republican; chairman of the Ford Foundation and the Council on Foreign Relations.”

It was McCloy’s role as high commissioner during the occupation of Germany that illustrates both the advantages and the limitations of mandarinism. From his years investigating and litigating the Bethlehem case, he came to know many leaders of German industry. As a corporate lawyer, he understood how to enlist their help in building a stable and prosperous new federal republic as a bulwark against the Soviets. But the price of the German economic miracle that transformed the ruins of German cities was McCloy’s reluctance to prosecute many corporate officials complicit in slave labor and the Holocaust.

The two decades from the end of the Second World War to the escalation of the Vietnam war in 1965 was a golden age of mandarinism, when lawyers and academics took the edge off partisan issues, though sometimes with further ethical costs. Potential conflicts of interest involving the clients of lawyer-mandarins went largely unexplored, at least by Establishment media. Advice in one case may have been shaped by personal vulnerability. A few years ago, it was revealed that President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s highest national security aide, an old-family Bostonian named Robert Cutler, secretly gay, had drafted the presidential decrees virtually equating homosexuality with disloyalty, forcing thousands out of government careers. Cutler was a lawyer. In his study of American intellectuals and war, the historian Bruce Kuklick has noted that Eisenhower took away from his short presidency of Columbia a suspicion of academics: “He did not want ‘a lot of long-haired professors’ to examine nuclear policy. ‘What the hell do they know about it?’ ”

Halberstam created the impression in The Best and the Brightest that the mandarins were at first united behind Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policy. But this was not necessarily the case, especially with the giants of the older generation. Benjamin Cohen, who continued to hold important advisory roles in Democratic administrations after the New Deal years, was Senator John F. Kennedy’s disarmament adviser, opposing intervention in Vietnam. In their book on the pillars of the midcentury Establishment, The Wise Men, Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas relate LBJ’s marathon browbeating of John McCloy to accept the ambassadorship to South Vietnam. McCloy did not conceal his pessimism about America’s prospects in the war and gamely withstood every command and insult (“yellow”) that Johnson could muster, finally “backing out” of the room.

But Halberstam did not dwell on such veteran Establishment people skeptical about American intervention in Vietnam. As he explains in his introduction, his book was not just a critical view of the Kennedy, Johnson, and early Nixon policies on the war, but a reply to his colleagues in journalism who seemed to him too close to those in power and too reluctant to challenge their authority. He quotes an encomium to Bundy by the celebrated syndicated columnist Joseph Kraft: a “figure of true consequence, a fit subject for Milton’s words: Deep on his front engraven / Deliberation sat, and publick care; / And princely counsel in his face.”

Halberstam was appalled by the deference shown by Kraft and other elite columnists seduced by Bundy’s patrician gravitas. He might have strengthened his case against the pundits by recalling that John Milton, in the second book of Paradise Lost, was describing not a celestial personage but Satan’s top mandarin, Beelzebub. The passage continues: “yet shon, / Majestic though in ruin.” In that verse, Beelzebub, addressing his fellow fallen angels, reminds them that they have renounced their titles in the divine court to be known henceforth as Princes of Hell.

The reputations of Kennedy’s and Johnson’s former mandarins never sank quite so low, yet they could still feel cast out of heaven, at least in part because Halberstam’s title soon became a sarcastic watchword. Bundy had lost his chance to be president of Yale or Harvard, and like Robert McNamara, he spent years analyzing where he and his colleagues had gone wrong.

Despite the fall from grace of the best and the brightest, Halberstam did not foresee how durable the mandarin institution would remain after the last helicopter left Saigon. Some presidents of both parties relied more on such people than others. There may have been just as many mandarins as ever during the administrations of Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, but journalists and the public were interested in only a few, like Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and Reagan’s economics guru Arthur Laffer.

The fall of the Soviet Union and the related rise of Islamist militance brought mandarins into focus again. The end of the bipolar world called out for new ideas and thus for a new generation of experts. Halberstam had turned to other themes, but the coming of Bill Clinton and his successors sparked a new wave of mandarin studies by leading journalists.

Twenty-two years after the release of The Best and the Brightest, David Ignatius, a Washington Post editor, discovered in 1994 that there were more mandarins (he called them meritocrats) afoot. With unusual access to mandarin circles, Ignatius (who himself had mandarin credentials) revealed in “The Curse of the Merit Class” in February 1994 that a minimum of 15 Rhodes Scholars were serving in the Clinton administration, six of them on the White House staff, most already connected through a network of foundations and think tanks; eight cabinet members, including Clinton himself, were members of the Council on Foreign Relations, which had emerged from Lippmann’s Inquiry 70 years earlier.

If they were so smart, Ignatius wondered, why was the administration facing such difficulties in health care reform and making peace in the former Yugoslavia? He found one clue in the conferences organized by a little-known organization to which Clinton and most of his foreign policy staff belonged, the Aspen Strategy Group, which gathered at a luxury resort at the historic Wye Plantation on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. (As recently as the mid-’90s, it did not seem to disturb either the group or Ignatius that the future abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, who grew up enslaved there, had written about its deplorable conditions.)

Quoting a phrase of the legendary critic George Steiner, himself a Rhodes Scholar, Ignatius found the mandarins to be “steely trimmers,” British-style intellectuals brilliant at cutting down others’ ideas but reluctant to advance bold ones, especially deep convictions that might be vulnerable to attack. The jargon of arms control muddled thinking about the essentials, Ignatius concluded. His description of the varied backgrounds of Bill Clinton and his lieutenants (Strobe Talbott, Robert Reich, Ira Magaziner, George Stephanopoulos) showed how the Rhodes competition had brought together a fresh cohort.

Behind the varied origins of these men, Ignatius found a troubling uniformity and narrowness of thought ill suited to a world no longer dominated by the old American-Soviet rivalry. This was an elite, he discovered, trained to fight an obsolete war. He quoted another journalist, Nicholas Lemann, who feared the new mandarins were “more Darwinian, more convinced of its superiority, than the old Protestant Establishment was.” Abruptly shifting into reverse gear, as though fearing retribution from on high, Ignatius ended his jeremiad on a conciliatory note. These people were really smart; he concluded that they were learning, they were becoming more successful. But the drift of the piece remained skeptical.

With the George W. Bush administration and the aftermath of the September 11 attacks came a new breed of mandarins from the same elite institutions as the Clintonians, but with different intellectual pedigrees. These were the Vulcans, as the writer James Mann has described the team supporting Bush’s drive to war in Iraq. Not all the Vulcans were mandarins in the Ivy League–Oxbridge sense. Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld certainly were not. But the Vulcans included one of the first famous Black mandarins and one of the few women, Condoleezza Rice, as well as Paul Wolfowitz, a student of neoconservative philosopher Leo Strauss and political scientist and nuclear strategy consultant Albert Wohlstetter. The chaos and looting that followed initial American success in Iraq later led to an extended campaign against one of the most potent jihadist movements, the Islamic State (ISIS), defeated at horrendous cost in Iraqi and American lives and treasure. The reconstruction of Iraq by a new generation of Americans contrasted with the resounding success of transitions to democracy supervised by American occupying forces in Germany and Japan after the Second World War. The comparison is not entirely fair, because both Axis powers were historically strong states, relatively homogeneous and hierarchical. Iraq was a comparatively new state, the artificial creation of the Great Powers after the First World War.

Left: Walter Slocombe briefing reporters in 2003; right: Paul Wolfowitz with a wounded soldier and family, 2002 (R. D. Ward/U.S. Department Of Defense)

Mandarins were once again drawn into the controversy. Wolfowitz has insisted that the media have exaggerated his role in planning the war, which he would have conducted differently. The decision to disband the Iraqi military has been the crux of the debate, and it is not entirely clear who gave the order and when. One of Clinton’s fellow Rhodes Scholars, Walter B. Slocombe, was chosen by the Bush administration to advise Paul Bremer, head of the American occupation. Slocombe, in charge of Iraqi security forces, found that Iraqi troops had abandoned their posts and gone home. Following discussions with officials in Washington, Slocombe concluded that the army was so ineffective and so permeated by Baathists still loyal to Saddam Hussein that it should not be recalled. It was not recalled, though U.S. military commanders in the region thought the army should be screened and reestablished. Slocombe is one of the quietest of the superstar mandarins: Princeton valedictorian, awarded a rare summa cum laude degree by Harvard Law School, postgraduate study of strategy in London, moving between a partnership in a leading tax litigation firm, Caplin & Drysdale, and senior positions in the Carter and Clinton administrations, including undersecretary of defense for policy from 1994 to 2001.

To his credit, Slocombe agreed to an on-camera interview for Charles Ferguson’s documentary about the occupation, No End in Sight. But whatever the truth of his replies, his performance united in scorn diverse reviewers of the film. The director told The Nation that “in a number of instances … he just lied. … I think he understood that he was not telling the truth.” David Denby’s glowing review of the film in The New Yorker called Slocombe’s denial of connection between his recommendations and the insurgency “madness.” Richard Schickel’s assessment in Time magazine: “slippery, sneering and supercilious.” Documents and further interviews may yet vindicate Slocombe and other mandarins. What such comments really show is how insulated even the most brilliant of the breed can become after years of valued private counsel in high places.

The answer to the failure of one set of mandarins was the emergence of another. When Barack Obama’s first appointments were announced, The Washington Post followed up the 1994 Ignatius article with a report from staff writer Alec MacGillis, “Obama Assembles an Ivy-Tinged League.” Of the president-elect’s 35 senior appointments, 22 were graduates of the Ivy League and a few other peer institutions. Nicholas Lemann (by then dean of the Columbia School of Journalism) weighed in again, as quoted by MacGillis: “The American meritocrats … are deeply invested in the idea that at a certain time in the past, [Ivy League alumni] in these jobs didn’t deserve them because they were aristocratic preppies, but that now they really deserve them. That’s the spin from the upper meritocracy.” But as Ben Cohen’s and Walt Rostow’s careers showed, the mandarinate was never a closed caste.

Just as Lyndon Johnson inherited many of Kennedy’s White House Action Intellectuals, Barack Obama’s choices have helped shape the Biden presidency after the Trump interregnum: Ben Rhodes has moved on to media commentary (his original specialty); Antony Blinken, who has held foreign policy positions since the Clinton administration, alternating with think tank appointments, is President Biden’s secretary of state; Jake Sullivan, who entered political life in the Hillary Clinton and Obama campaigns, is Biden’s national security adviser.

Ashraf Ghani, the president who fled Kabul in August 2021, showed the limits of a mandarin education. As an exchange student in Oregon, he fell in love with American democracy, eventually becoming a dual citizen. Exiled by political violence in his native country, he came to America and received a PhD in anthropology from Columbia University with a dissertation on the economic and political development of Afghanistan from 1747 to 1901. Genuinely idealistic about improving global well-being, Ghani joined the World Bank as an anthropologist after teaching at Berkeley and Johns Hopkins, traveling half the year to interview people on the ground to help get the best results for development projects. Yet as his government fell in Afghanistan, he could not mobilize his countrymen against a force far smaller than his American-supported army, blaming the United States for negotiating with the Taliban over his head.

Former Trump appointee Fiona Hill, February 2017 (Kuhlmann/MSC/Wikimedia Commons)

In the half-century since The Best and the Brightest appeared, academics and other journalists have exposed the limits and failures of the mandarins. Yet there is no sign that they are going away. Donald Trump’s attacks on the so-called deep state seem to be the latest sustained threat to mandarinism, but as the historian Robert Dallek observed during the 2016 election, Trump himself boasted that he knew and would appoint “the best people,” pointing proudly to his own degree from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. The one mainstream mandarin who did go to work for him, the British-born National Security Council appointee Fiona Hill, was appalled by Trump’s conduct and resigned. Trumpist nationalism is not so much anti-authority, however, as what might be called alt-thority, with its own credentialed experts. Trump’s first deputy assistant to the president for strategic communications in the National Security Council, Michael Anton (Berkeley, St. John’s College, Claremont Graduate School) is the opposite of a deplorable—a connoisseur of food, wine, and tailoring. A veteran Wall Street and political publicist, Anton represents the phalanx of Porsche populists who have arisen in response to the limousine liberals: countermandarins aspiring to countermand the progressive bureaucracy.

Across the political spectrum, men and women with mandarin credentials are bypassing appointive careers to seek public office directly. Hillary Clinton (summa Wellesley, first in her class at Yale Law School), who used the office of the first lady as a mandarin policy laboratory, was one of the first since Woodrow Wilson himself. Barack Obama (Columbia and Harvard Law School, magna) found the right political mentors in Chicago. Biden’s secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg, is not only a Harvard graduate (magna) but also one of the minority of Rhodes Scholars who earned the Oxford A.B. summa cum laude. On the Republican side, Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, notorious for raising his fist during the January 6 Capitol riot, graduated from Stanford with highest honors in history and was an editor of the Yale Law Review. Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida was a star athlete and magna graduate at Yale and also took honors at Harvard Law School. And Texas Senator Ted Cruz was a national champion debater at Princeton and a magna graduate of Harvard Law School. Trumpist voters are happy with such credentials, provided they are used to advance Trump.

The educational conveyor belt has never halted, continuing to crank out the highly credentialed. At some level the mandarins are aware of what is apparent to anyone who works with a range of academics or visits many colleges. There are great scholars and brilliant students almost everywhere. Why are so many of the mandarins graduates of only a few institutions? Is it because these institutions have learned to cultivate a self-confidence, a sense of specialness that creates invisible armor? A former visiting faculty member at both Cornell and Yale has noted the greater ambition of Yale undergraduates. They were not necessarily more gifted than their Cornell counterparts, but the faculty seemed to convey greater political expectations, to which they often rose. Ivy League hegemony is based not on pure competition (like that of the original Chinese mandarin examinations) on the one hand, or entirely on old-boy and old-girl networks (like that of Rhodes Scholar nominators) on the other, but on mentorship instilling a sense of mission.

One enduring facet of mandarinism is that although its members are aware of the errors of their predecessors, they are always confident that they can learn from these mistakes and do policy right this time. The true risk to the mandarin, paradoxically, is not the passion for success but the disadvantage of unbroken success and cumulative advantage that so many experience, what the sociologist Robert K. Merton called the Matthew Effect (“For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance,” Matthew 25:29). The confidence conferred by mandarin education can be seductive when not tempered by career reversals. Men and women sometimes fail because in eluding failure they come to ignore their own fallibility. Professorial careers can promote self-deception, according to Robert Hutchings, who has taught at the University of Texas and Princeton and has observed experts as chairman of the National Intelligence Council. “This is because they have been socialized in a world of theory in which their ideas have no consequences. How many have ever made a decision that had life-and-death consequences? They simply opine, often without any after-the-fact accounting, so they rarely subject their judgments to critical reappraisal.” Quantitative advisers like McNamara and Rostow have an additional problem. “There is real danger,” mathematician Jordan Ellenberg has written, “that, by strengthening our abilities to analyze some questions mathematically, we acquire a general confidence in our beliefs, which extends unjustifiably to those things we’re still wrong about.” (McGeorge Bundy had an undergraduate mathematics degree from Yale.) Halberstam quotes Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn’s famous reply to Lyndon Johnson’s praise of the advisers he had inherited from Kennedy: that Rayburn would feel better if “just one of them had run for sheriff once.”

Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, June 2021 (Lev Radin/Alamy)

Looking back on the 50 years following publication of The Best and the Brightest and the repeated focus on the role of mandarins—by themselves and others—it may be that we have blamed as well as credited them for too much. When the head of scientific research at Los Alamos, J. Robert Oppenheimer, confessed a sense of guilt over Hiroshima, President Harry S. Truman would have none of it. Truman alone had authorized dropping the bomb. It was his responsibility, not that of the advisers. Evan Thomas, supporting the judgment of another Harvard mandarin, law professor Francis M. Bator, says that because of Halberstam’s “need to set up the idea of the Best and the Brightest—and to enhance the tragedy of their fall—[he] overstated the sway of the Harvards over Johnson. The real tragedy was that LBJ did not listen to Bundy, or to his brother Bill, or to McNamara.”

So it was over the decades with other policies regarding Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, China, and especially Russia. Presidents decided. Not National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski but Jimmy Carter ordered the disastrous hostage rescue during the Iran crisis, probably prolonging the hostages’ ordeal and certainly costing him the 1980 presidential election. Not a subsequent adviser, Anthony Lake, or Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott but Bill Clinton was responsible for the post-Soviet diplomacy of the 1990s that helped prepare for the presidency of Vladimir Putin. Bad decisions cascade. Sometimes the choices available to leaders recall the adage of Warren Buffett about the corporate scene: when a management with a reputation for brilliance meets an industry with a reputation for bad fundamentals, it is usually the reputation of the industry that survives.

Before Halberstam’s book, the Harvard mandarins of the New Frontier were admired as a vanguard of new thinking. Even now, opinion surveys show that the public respects higher education even more than religion. Anti-intellectualism, like so many other phrases, oversimplifies a deep ambiguity.

Did mandarins steer presidents and legislators in the wrong direction, serving special economic interests? Or did they curb the most dangerous impulses of the military at crucial times, preventing a third world war? It is easy to recall the greatest gaffes of the mandarins, who like the rest of us are often unable to escape either wishful thinking or irrational fear. In 1933, Walter Lippmann, having changed his mind about FDR, urged the newly elected president to declare himself dictator. In the same year, he called a speech by Adolf Hitler “the authentic voice of a genuinely civilized people.” In 1950, John von Neumann, cofounder of nuclear weapons, modern computers, and game theory, was quoted in Life magazine urging an immediate preemptive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. (“If you say why not bomb them tomorrow, I say why not today? If you say today at five o’clock, I say why not at one o’clock?”) Not surprisingly, von Neumann, the greatest human calculator of his time, often lost at poker. Bill Clinton’s secretary of Defense, William Perry, an outstanding mathematician and engineer, not only became a board member of the fraudulent blood-testing startup Theranos but even praised its founder, Elizabeth Holmes, since convicted of fraud, as a genius greater than Steve Jobs because she had “a big heart.” (Social psychologists have found that the most intelligent people can be the easiest to deceive.)

Americans are members of what I have called Immoderation Nation, swinging between uncritical admiration and scorn. America’s challenges, its separation of legislative and executive powers, and the frequent clashes of competing bureaucracies in Washington combine to require high-level independent advice to presidents. The drawback of this institution is, as Henry Kissinger wrote of McGeorge Bundy in his White House memoir, that the neophyte mandarin has not had the government experience to realize the potential limits of his or her intellect. I hope the mandarins of the future will include more people who, unlike the Bundys of the world, have crashed once or twice on the fast track. Until then, the best credo I know was proposed to me decades ago by legal history scholar Robert W. Gordon. An intellectual, he observed, is “one who believes that 1) the world is run by fools, and 2) I could do no better.”