“Measure for Measure” will return on July 5. In the interim, please let us know in the comments section below what your favorite American symphonies are.

That distinctly European art form known as the symphony began to flourish on American soil in the latter part of the 19th century. Not surprisingly, the earliest American symphonists composed in a style heavily indebted to Brahms, Schumann, and Mendelssohn, among others. Only with the advent of a certain insurance executive–cum–maverick composer named Charles Ives did the American symphony begin to truly come into its own.

In last week’s column about Walter Piston, I happened to list a few of the most essential American symphonies. Immediately I began thinking of works that I’d neglected to mention. So this week, let’s expand the list. For the sake of a nice, neat number, I am identifying 25 great works—hardly a comprehensive tally, and somewhat arbitrary. Looking over the finalists, I began second-guessing at once: Why no Virgil Thomson or David Diamond? Why Bernstein’s First and not his Second? Why not Ives’s Third? I have not, moreover, included symphonic works that do not bear the title Symphony; therefore, I have left out Samuel Barber’s Essays and Joan Tower’s Concerto for Orchestra. What do you think I ought to have included? Please let me know in the comments sections below. I’ll list the best of your choices in my next column.

Symphony No. 1 (1859)

Louis Moreau Gottschalk

The New Orleans–born Gottschalk was known primarily as a virtuoso pianist (he was admired by Chopin, among others) and as a composer of pieces for his instrument. His first symphony, subtitled A Night in the Tropics, is in two movements, the first leisurely and endearing, the second an innovative synthesis of Caribbean and Louisianan motifs.

Symphony No. 2 (1879)

John Knowles Paine

Paine, the elder statesman of the cadre of composers known as the Boston Six, was the first American to gain wide renown as an orchestral composer. His First Symphony established his reputation, but his second, subtitled “In Spring,” is for me the better work—a grand, at times turbulent, Romantic affair (the broad Adagio being especially beautiful), with the composer’s affinity for Schumann felt in many of its passages.

Symphony No. 2 (1886)

George Whitefield Chadwick

The New Englander Chadwick infused the classical and Romantic idioms he inherited with elements of the Scots-Irish folk tradition. Although Bernstein famously dismissed him, the music critic Olin Downes wrote that “no other American composer … produced as much important music in as many different forms as George Whitefield Chadwick.”

Afro-American Symphony (1930)

William Grant Still

Languid and bluesy, folksy and hymn-like, with passages that call Dvořák to mind—Still’s symphony is an homage to the suffering and hope of enslaved Americans. It’s probably the

the most famous work by a black American composer, and it influenced the likes of George Gershwin.

Negro Folk Symphony (1934)

William Levi Dawson

Shamefully, I had never heard of this piece or its Alabama-born composer until the music historian Joseph Horowitz told me about them not long ago. The symphony reflects Dawson’s abiding interest in spirituals, and though Leopold Stokowski championed it upon its completion, Dawson revised the work in 1952, adding several West African themes following a journey to that region.

Symphony in E minor (1894)

Amy Marcy Beach

The folk music of England, Ireland, and Scotland lies at the heart of this work, the first symphony by an American woman. Beach was a prodigious talent, and her unjustly neglected symphony, called the Gaelic, is full of charm and rich thematic material.

Symphony No. 4 (c. 1920)

Charles Ives

Ives changed everything—to be sure, the American symphony came of age with him. Perhaps it’s because of the piece’s patriotic temperament—there are hymns galore and extended quotations of “Columbia, the Gem of the Orient”—that I always listen to the Symphony No. 2 on the Fourth of July. Ives’s Holidays Symphony is America’s answer to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons: a wild and evocative conflation of the brutal and sentimental. The Fourth Symphony is an even more impressive work and is perhaps the crowning glory of Ives’s mature style—a grand amalgam of complex rhythms and polytonality.

Symphony No. 2 (1930)

Howard Hanson

For four decades, Hanson served as the director of the Eastman School of Music. His Symphony No. 4 won a Pulitzer Prize, but his Second Symphony, the so-called “Romantic,” is my favorite: lush, lyrical, and wonderfully nostalgic.

Symphony No. 3 (1939)

Roy Harris

With its syncopated rhythms, folk elements, and robust melodies and harmonies, Harris’s Third may be the most American of symphonies, in some ways a declaration of independence from the European symphonic tradition.

Symphony No. 1 (1942)

Leonard Bernstein

During this Bernstein centenary year, performances of the composer’s most popular scores—West Side Story and Candide, to name just two—abound. The polymath Bernstein, however, felt that his more serious scores always got short shrift. Among these is his First Symphony, subtitled Jeremiah, featuring a mezzo-soprano soloist singing texts from the Hebrew Bible.

Symphony No. 4 (1942)

George Antheil

If you only knew Antheil’s avant-garde works, you might mistake his Fourth for a long-lost piece by Shostakovich. Antheil wrote this intense, angular, militaristic, and sarcastic symphony while working as a wartime correspondent for the Los Angeles Daily News.

Symphony No. 2 (1943)

Walter Piston

Piston was often dismissed as an “academic” composer, due to his long tenure in the Harvard music department and authorship of several essential textbooks, but his symphonies are imaginative, powerful, and compelling. I would love to have included the Third, Seventh, and Eighth symphonies (the latter a brooding, mysterious, and haunting 12-tone work), but I’ll restrict myself to the melancholy and bluesy Second, which contains one of the most elegiac slow movements in the repertoire.

Symphony No. 3 (1946)

Aaron Copland

Some would call this populist work the apotheosis of the American symphony, with the composer’s Fanfare for the Common Man prominent in the fourth movement and the prevalence of that expansive Western idiom that Copland practically invented.

Symphony No. 8 (1968)

Roger Sessions

This 50-year-old masterpiece by another woefully underappreciated composer is mournful and explosive, menacing and tender, with a danse macabre of a finale that darts devilishly to an elliptical though magical ending. There are echoes of Webern and Berg, and throughout one senses the feeling of defiance so typical of Sessions’s approach.

Symphony No. 3 (1941)

William Schuman

Schuman wrote 10 symphonies but withdrew his first two essays in the genre. The eloquent, occasionally somber Third is my favorite, with a glorious, hyper-intense finale that lingers in my mind every time I hear it.

Symphony No. 2 (1944)

Samuel Barber

Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942, Barber became a corporal in the Army Air Force. He wrote his Second Symphony in tribute to that service, an expression of the excitement and daring of flight. Barber later grew dissatisfied with the work and withdrew it, yet it remains a startling, relentless, and distinctive work.

Symphony No. 3 (1959)

Ned Rorem

Recognizably American, yet suffused with French influences, Rorem’s Third is almost defiantly tonal (composed in an age when tonality was ridiculed in certain circles), a work of power, jazzy playfulness, and grace. That Rorem is probably America’s finest composer of art song is evident in the work’s innate lyricism.

Symphony No. 1 (1982)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

From the opening meditative passages of this symphony, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1983, I feel a certain anxiety; the tempestuous and ominous work that unfolds, also called Three Movements for Orchestra, is brilliantly sonorous and emotionally taxing.

Symphony No. 5 (1985)

George Rochberg

Bernstein isn’t the only composer whose centenary falls this year. Rochberg (1918–2005) was a devotee of serialism until his 21-year-old son died of a brain tumor in 1964. After that, he turned to a more Romantic style. His Fifth Symphony is an intense work redolent of Mahler.

Symphony No. 1 (1986)

Christopher Rouse

I have a thing for symphonic slow movements, in particular those sprawling, cosmic narratives in late Bruckner, so Rouse’s First has a special appeal for me. Rouse quotes from Bruckner’s Seventh, even using that work’s characteristic scoring of four Wagner tubas.

Symphony No. 1 (1989)

John Corigliano

For quite some time, Corigliano resisted composing an old-fashioned symphony. When he finally embraced the idea, he ended up creating a haunting elegy to those lost during the AIDS crisis—a powerful work of personal and public mourning.

Doctor Atomic Symphony (2007)

John Adams

If ever there was a musical emblem of our nuclear age, this is it. Adapted from Adams’s opera of the same name, depicting J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project, the symphony begins like a far more menacing incarnation of Brahms’s First. What follows is relentless, frightening, and often incantatory.

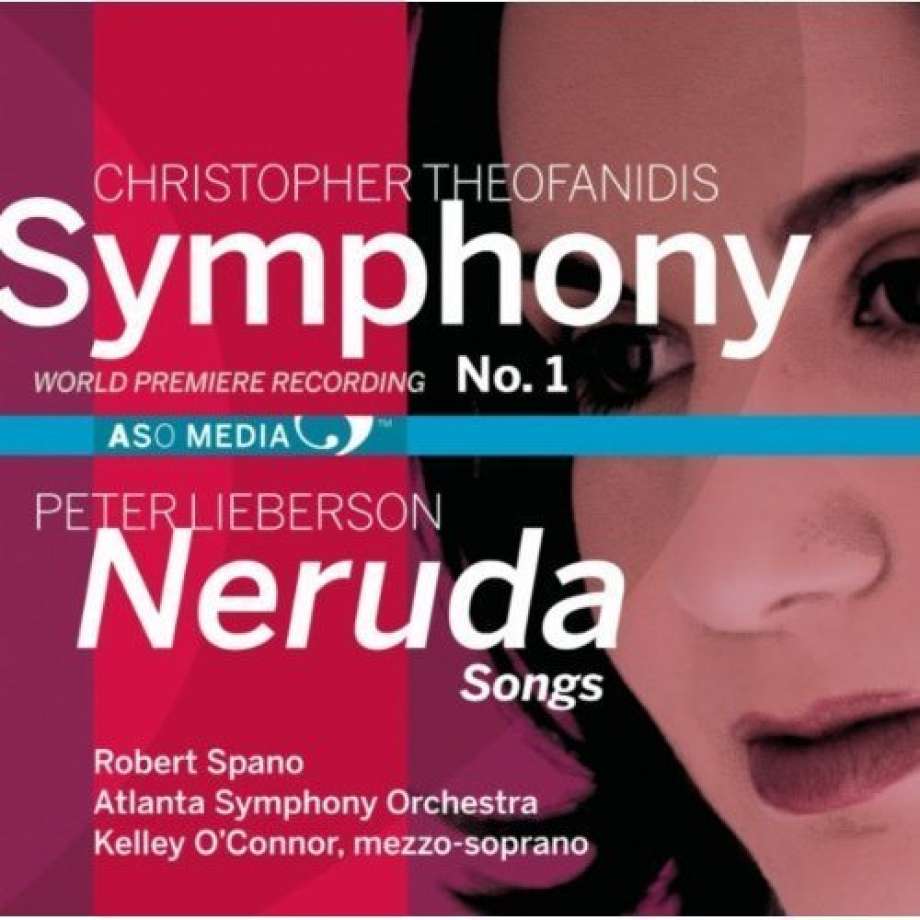

Symphony No. 1 (2009)

Christopher Theofanidis

Theofanidis’s sound world is unlike any other, its idioms utterly accessible. After a joyous woodwind opening that suggests the birth of civilization (or perhaps merely the dawning of day), the work is driven and hectic—almost unbearably energetic at times. The symphony is expertly orchestrated, a sonorous study of darkness contrasting with light.