One afternoon some 30 years ago, I was listening to the radio in my bedroom, when Henryk Wieniawski’s Violin Concerto No. 1 came on the air, just as a nasty thunderstorm moved in—the kind of late-afternoon storm typical of a Florida summer. I remember how quickly the sky blackened, lightning flashing in the distance, miniature waves churning up in the pond out back, rain driving in angled sheets. The weather added a frisson of danger to a performance that was itself tempestuous, and the confluence of the two—the sounds coming out of my cheap portable music player mingling like magic with the noise of the storm—helped make the experience unforgettable. I was a teenager at the time, fond of pieces like the Wieniawski, that is, heroic, romantic, virtuosic repertoire, and that particular recording left me in awe.

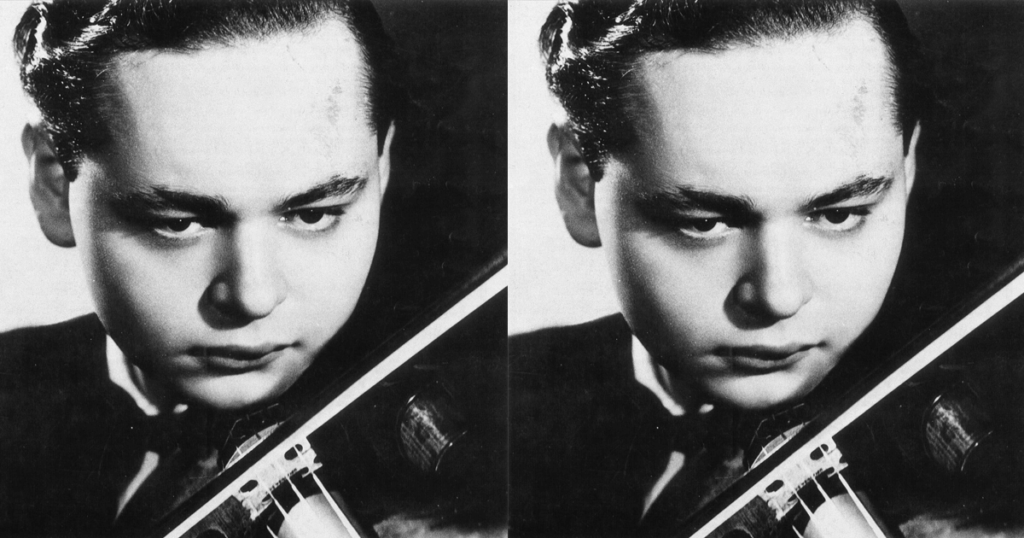

The violinist was Michael Rabin, an artist I used to revere, for few others had so opulent a tone, such finesse, or the ability to play the most difficult passages with insouciance and aplomb. When I was nine or 10 and living in Illinois, my violin teacher had given me a cassette recording with Rabin playing some popular showpieces, including a red-blooded version of Camille Saint-Saëns’s “Introduction and Rondo capriccioso” that remains, to this day, my favorite interpretation of that piece. Over the years, I wore that cassette out, and I was equally taken with the violinist’s recording of Niccolò Paganini’s 24 Caprices, which my father had in his collection. But there was more to the Rabin story than his artistry. I knew he’d lived a troubled life, that he had been a phenomenal child prodigy who died at 35. In my household, his name carried a certain mystique, an almost mythical aura.

He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.”

This routine became even more rigid when Rabin switched to the violin. His father gave him his first lessons—and quickly realized that he was well out of his depth. So he sought out one of the finest pedagogues of the day, Ivan Galamian, with whom Rabin flourished. At the age of 10, he performed the fiendishly difficult Wieniawski Concerto No. 1 with the Havana Philharmonic. Two years later, he recorded 11 of the Paganini Caprices. At 13, he played Henri Vieuxtemps’ Violin Concerto No. 5 at Carnegie Hall, and he appeared at that same venue two years later, this time with the New York Philharmonic and Dmitri Mitropoulos. The work on the program was another finger-breaker: the Concerto No. 1 by Paganini. “Hear Rabin and know that the Gods have not forgotten the violin,” read the headline of one New York Times review. More important than the glowing criticism was the reaction of the musicians with whom Rabin worked. For Mitropoulos, he was “the genius violinist of tomorrow, already equipped with all that is necessary to be a great artist.” George Szell said that the boy was “the greatest violin talent that has come to my attention during the past two or three decades.”

In the 1950s, Rabin signed a recording contract with EMI that allowed him to produce classic accounts of many concertos of the Romantic era, along with numerous shorter works. He excelled especially in the repertoire written by the violinist-composers Paganini, Wieniawski, and Vieuxtemps, not only because of his superlative technique (tenths, octaves, up-bow staccato, multiple stops, ricochet bowing, cascading arpeggios—nothing troubled him in the least), but because of the beautiful, singing tone he produced on his Guarneri del Gesù. In the wrong hands, a Paganini concerto can sound like 30 minutes of trite histrionics—virtuosity for its own sake. Rabin, however, knew how to sing. He played a Paganini concerto as if it were composed of arias, recitatives, and choruses.

He embarked on a demanding career, playing concerts all over the world, yet it soon became evident that he was utterly ill-equipped for such a life. He may have been a master of his craft, but as Feinstein writes, “when it came to life and the fragile passage of wunderkind to mature adult, [Rabin’s] trajectory was less certain.” Totally spoiled as a child, with every decision having been made for him, he now had to cope with the shock of adulthood. This, after never really enjoying even a semblance of a normal childhood. By the age of 10, he was no longer attending public school or playing in the neighborhood. His relations with other children were severely restricted—his mother insisting that he devote his life to practice. “These days it would probably be called child abuse,” Rabin’s sister told Feinstein. “He probably got hit if he played a note out of tune sometimes. Or she would demand that he play a passage 100 times.” It’s no wonder that Rabin would turn out to be a socially awkward adult, his psychological development stunted, and that he would be vulnerable to a host of emotional problems.

In the early 1960s, at the age of 27, Rabin experienced a nervous breakdown. He withdrew from family and friends, becoming a semi-recluse. He also developed a paralyzing fear of falling off the stage in the middle of a performance. He developed stomach pains severe enough to warrant medication. And as his anxiety and feelings of loneliness intensified, he increasingly turned to barbiturates. “It was a difficult and sad time,” he would later recall. “I call it my Blue Period.” He quit performing for seven months and never made a studio recording again.

Another factor in Rabin’s crackup, however, had nothing to do with upbringing, but with how he was perceived artistically in those difficult post-prodigy years. In that same 1971 interview, Rabin described the virtuoso’s plight, in comments that are as relevant today as they were then:

When you’re no longer a child prodigy, you continue on because you’re expected to. But then you have to shape up or ship out. In the years, say, from 16 to 26, everyone in the music field starts to pull you apart. They say, ‘He’s not a mature artist. He plays fast and loud and Paganini all the time and he’s too young to play Beethoven and Brahms.’ In your mid-twenties you do play Beethoven and Brahms and some people say, ‘Better he should play Paganini.’

Part of the problem—a good part of the problem—is the business itself, the way child prodigies are marketed and consumed. Audiences do not pay money to hear an eight-year-old commune with some quiet score, plumbing its depths for profound insights. They want to see children executing the near-impossible. They want fireworks, fingers traveling up and down the fingerboard in a dizzying blur, runs of double stops and octaves, and the bow working miracles. But then the children grow up, and now the critics expect sage artistry rather than empty virtuosity. The trouble is, that earlier impression of the daredevil, the circus trickster, clings all too stubbornly; it can dog an artist until the end, long after he or she has graduated, so to speak, from Paganini to Brahms.

Nathan Milstein, David Oistrakh, and Joseph Szigeti may have been more thoughtful artists than Rabin, but then, they had the luxury of longer lives in which to ripen. Rabin did attempt a comeback, playing 21 concerts in the 1963–64 season and nearly 60 concerts during the following one. Extensive therapy sessions had apparently helped. (“I don’t know why there’s all this hush about people admitting they’re seeing an analyst or a therapist,” he said in 1971. “When you finally decide to go into therapy I think it’s reason to celebrate, not to whisper about.”) But the state of his mental health continued to be the subject of extensive gossip in the music world. Orchestra managers and concert promoters, believing that Rabin was unstable or addicted to drugs, shied away from booking him. Musically, he was still in top form, and his personal life appeared to be stabilizing; he told close friends that after flitting about with many women, he had finally, truly fallen in love. On January 19, 1972, however, Rabin slipped on the parquet floor of his West End Avenue apartment, hit his head on a chair, and died. The coroner’s report noted the heavy presence of barbiturates in his blood.

For connoisseurs, those early EMI recordings remain magical and definitive. But some of Rabin’s later performances, given shortly before his death, offer invaluable glimpses into the kind of artist he was evolving into. Consider one concert from February 26, 1970, when Rabin appeared with the San Diego Symphony under the direction of its conductor, Zoltan Rozsnyai. Rabin’s performance of the Brahms Violin Concerto was broadcast on the radio and released commercially seven years ago, as part of a collection of previously unpublished recordings. It’s a deeply satisfying, assured, and mature performance, above all. There’s the same lovely lyricism, the same fire, the same burnished, luxuriant tone, but with a deep understanding of shape and musical architecture. Perhaps the most striking thing about the interpretation is how unsentimental it is. Indeed, in much of the phrasing, I can’t help detecting an underlying sadness. Not that there aren’t traces of the old brilliance. The first-movement cadenza, for example, is something to behold, with Rabin’s idiosyncratic phrasing giving the impression of invention and improvisation. The sound of this recording is far from ideal, and the San Diego Symphony, though fully committed and strong, isn’t exactly the New York Philharmonic. But what if Rabin had lived long enough to fulfill one of his dreams—to record the Brahms and Beethoven concertos in the studio? Imagine if he’d teamed up once again with the New York Philharmonic, or the Philharmonia of London, which had backed him less than two decades before. What might they have produced? On the evidence of that February night in San Diego, it could have been a record for the ages.

Listen to Michael Rabin perform the Wieniawski Violin Concerto No. 1, with Adrian Boult leading the Philharmonia Orchestra:

And listen to Michael Rabin perform the Brahms Violin Concerto in his radio broadcast with the San Diego Symphony, Zoltan Rozsnyai conducting: