The first time I heard the music of William Grant Still—it was in the car many years ago, and I had turned the radio on midway through the piece—I assumed I was listening to George Gershwin. Little did I know how many people have made the same wrong assumption about Still’s Afro-American Symphony, probably the most famous work by a black American composer, or that the question of just who influenced whom was a matter of some debate.

Still was born in Woodville, Mississippi, some 35 miles south of Natchez, the son of mixed-race parents who were both learned and musical. His father, well known for his cornet playing (he founded a brass band and was revered by Woodville’s black community), died under mysterious circumstances when Still was an infant. Wanting to raise her son in a more tolerant racial environment, Still’s mother moved the family to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught public-school English while looking after the boy’s cultural upbringing. She took him to song-filled church services and to Saturday salons where prominent black musicians, writers, and actors performed. At home, Still’s grandmother sang hymns and Negro spirituals, and his new stepfather did his part, too, buying him a violin, introducing him to musicals, and acquiring a phonograph that opened up for him the world of grand opera. Still was 16, already adept at a few instruments, but it was hearing Puccini and Wagner that made him determined to become a composer.

His mother, however, envisioned a more lucrative and stable future for him, insisting that he attend Wilberforce University in Ohio. (Admission was no issue, Still having been the valedictorian of his class). There, he began arranging music for band and small ensembles, more intent than ever on making a life in the arts. He met a young woman, got married, and left Wilberforce just two months shy of graduating.

It wasn’t easy—supporting a wife, and soon a child, on a salary earned from playing the oboe and cello in various orchestras and bands. He got a job in Memphis with the legendary blues musician W. C. Handy, arranging and orchestrating music at his publishing house and touring as a musician with his band. Traveling from gig to gig, Still encountered racial violence for the first time in his life, seeing black men beaten and lynched on the streets of small Tennessee towns. After a period in the Navy, Still enrolled at Oberlin, where he studied composition and music theory. When he could no longer afford tuition, he dropped out and got a job with Handy again, this time in New York City. He continued to play gigs when he could, joining the orchestra of the ragtime pianist and composer Eubie Blake, and undertook studies with two prominent teachers with wildly different temperaments: George Chadwick at the New England Conservatory, where he received a scholarship, and Edgard Varèse, who gave him private lessons free of charge. “When I was groping blindly in my efforts to compose,” Still later wrote about the French-born avant-garde composer, “it was Varèse who pointed out to me the way to individual expression and who gave me the opportunity to hear my music played.”

His education complete, the composer continued to struggle, once nearly freezing to death when his coat was stolen in the dead of winter, another time going days without substantial food when his violin was destroyed as part of a nightclub comedy act. Yet slowly, recognition came his way. He honed his skills as an arranger of Negro spirituals and pop music, collaborating with Paul Whiteman, Artie Shaw, and Sophie Tucker. Meanwhile, Varèse and Howard Hanson, director of the Eastman School of Music, championed his orchestral work and helped secure performances of this music. It was Hanson who led the premiere of Still’s first significant piece, the Symphony No. 1, which the composer completed in 1930 and dubbed the Afro-American Symphony.

Hanson was taken by the piece’s “lovely melodies, gorgeous harmonies, insidious rhythms and dazzling colors” and saw in it the makings of a “purely American idiom,” one “couched in the ‘grandeur of simplicity’—a simplicity which was the ‘measure of genius.’” Both the public and the critics seemed to concur, with audiences abroad particularly smitten: in Berlin, in 1933, the audience roared so insistently upon the symphony’s conclusion, that the orchestra had no choice but to play the third movement twice more. In the New York Post, the critic John Briggs wrote: “I have long been a believer in Mr. Still’s talent and last night didn’t change my mind. Mr. Still may well become the American Tchaikovsky—and before you turn up your nose, kindly reflect that it is much harder to be the American Tchaikovsky than to be the American Hindemith. The former requires genius; for the latter all you need is brains.”

The three-movement work is a splendid amalgam of European symphonic structure and American style. The opening line of the first movement, for example, is a bluesy solo lament on the English horn, which sets a languid mood that brightens later on, with the recapitulation of the melody. There’s a lovely folk tune that emerges out of some improvisatory passagework, but the heart of this episodic movement is a passage reminiscent of Dvořák—the “American” Dvořák of the New World Symphony and the String Quartet No. 12. We know, given that Still transcribed poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar into his working notebooks, exactly what this music is meant to evoke: the mourning and the hope of enslaved Americans. In this context, the appearance of various spirituals makes perfect sense, especially in the second movement, a beautiful and melancholy adagio. There’s some exquisite writing for strings here, and a general mood of disquiet relieved only by the calm of the final note.

In the third movement, a movement of gorgeous hymns, the question of Gershwin really comes to the fore (though parts of the first movement do put one in mind of Porgy and Bess). Before we get to all that sparkling and syncopated exuberance, we hear the horns play the main theme of “I’ve Got Rhythm.” There it is—unmistakable. But was Still quoting from Gershwin’s Girl Crazy, which had premiered a mere two weeks before he began work on the Afro-American Symphony? Or was the melody really Still’s to begin with? The answer, it turns out, isn’t clear. Eubie Blake, for one, always maintained that Gershwin had stolen the tune from Still, having heard him play it one day on the oboe. And though many white songwriters of the time did indeed borrow from black musicians—call it the anxiety of influence or mere appropriation—Still himself was ambiguous on the matter. In an essay published in 1944, he wrote that Gershwin participated in

a great deal of unconscious borrowing from several sources (not always the Negro) and that he did some conscious borrowing which he apparently was generous enough to acknowledge. … Quite often colored musicians claim to have had their creations or their styles stolen from them by white artists. In many cases these tales may be dismissed as baseless rantings. But there have been so many instances in which they are justified that one cannot ignore all of them. I have learned this from my own experience and from the experiences of my friends in the world of music.

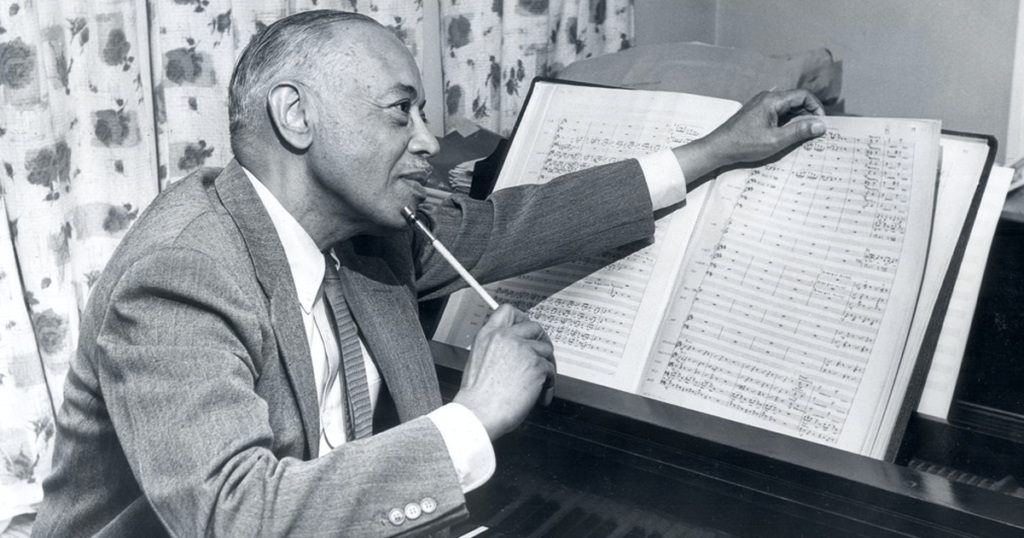

No matter, the work made Still a celebrity, though interestingly, he himself felt that he could have done more in its pages. “This symphony,” he wrote, “approaches but does not attain to the profound symphonic work I hope to write; a work presenting a great truth that will be of value of mankind in general.” He went on to compose many other pieces of distinction—performed by the likes of the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Boston Symphony, and Los Angeles Philharmonic—but after the disastrous premiere of his opera Troubled Island in 1949 (the crowds may have been enthusiastic, but the critics were merciless), Still’s career slowly faded, with fewer performances and commissions, and a cessation of recording activity. By this time, he had divorced, moved to Los Angeles, and married a Jewish pianist named Verna Arvey, having gone to Mexico to obtain their marriage certificate, interracial unions being illegal in California. Ensconced on the other coast, Still followed the Dodgers avidly, watched boxing on television, tended to his garden, and later gave talks in the city’s public schools, playing music and invoking themes of universal brotherhood and compassion. Once again running out of money, the man dubbed the Dean of African-American Composers was reduced to writing background music for The Three Stooges and Gunsmoke. He died in 1978, following a heart attack, a stroke, and a bout of dementia that had forced his institutionalization just a few years before.

Long before such terms as fusion and crossover were codified, William Grant Still was breaking down many an entrenched barrier, showing that jazz and opera, the blues and symphonic music could happily coexist—and that the idioms of the American South, the Caribbean, and indigenous America were worthy of high-cultural veneration. He wasn’t the only prominent black composer of his time (listen, for example, to William L. Dawson’s incredible Negro Folk Symphony of 1934, premiered by Leopold Stokowski), but without him, this distinctly American style would not have fully flourished.

Listen to Leopold Stokowski conduct the third movement of William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony, in this recording from the 1940s: