My mother and father were witty, ambitious people, charter members of the postwar meritocratic elite. His background was Jewish, hers Presbyterian. He came from Philadelphia, where his father sold ladies’ underwear, she from Winnetka, Illinois, where her father was a banker. Both my parents were atheists, not the angry, proselytizing kind that prevails in the current moment, but confident and serene. They met at Swarthmore.

I wouldn’t call their marriage happy, but it was certainly strong. Especially in its early days, their united differences gave it a kind of hybrid vigor. My father had a clear, powerful mind, a natural gravitas, and a room-filling presence, attributes that took him far. After 15 years of teaching economics at Williams College, he was called to Washington, D.C., to serve as an adviser to John F. Kennedy. Later, he was appointed budget director under Lyndon Johnson, and during the Nixon administration he became president of the Brookings Institution. My mother was pretty, clever, and multitalented. She brought her skills as cook, hostess, raconteuse, and thrifty household manager to the joint enterprise of furthering my father’s career.

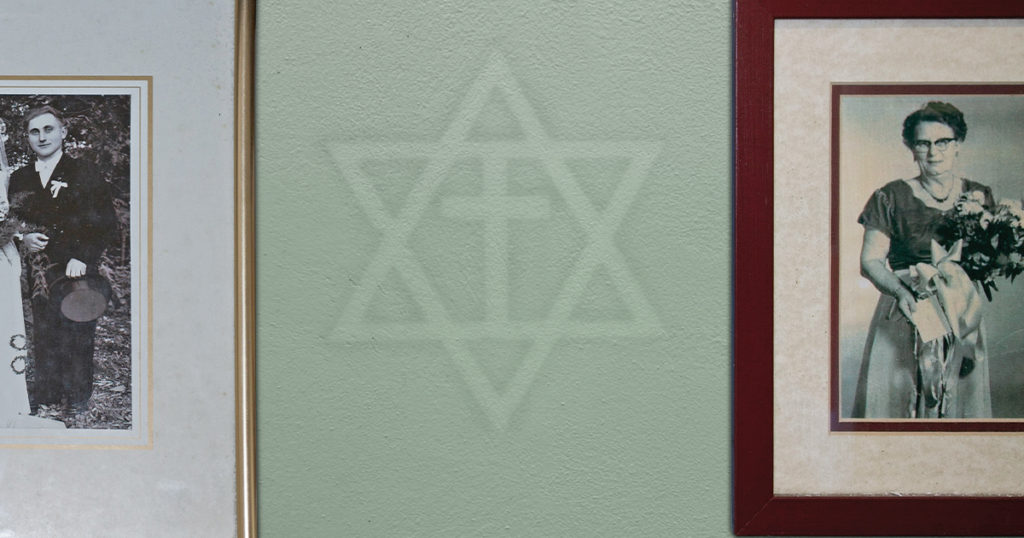

Of my father it could truly be said that he didn’t look Jewish. He was tall and fair and spoke without an identifiable accent. In an era when few people were sophisticated about wine, he knew provenances and vintages. When young, he was athletic; as a Rhodes Scholar, he had played lacrosse. He never tried to hide his background, but Jews were rare on the Williams faculty—he was one of the first to be hired there—and many people assumed he was as much a WASP as my mother. One who didn’t, I later learned, was James Phinney Baxter III, the college president, who referred to my father and his colleague Emile Despres as “those two Jews.”

Neither of my parents had grown up in an observant household; neither had been bequeathed belief. The relatives on the Jewish side of my family were resolutely secular. Though my maternal grandparents maintained their membership in the Presbyterian church, they kept their distance from faith. The only outwardly religious relative I recall on either side was my mother’s brother Joseph, who was a deacon (or something) in his Minneapolis church. But he was also a Republican, which for my parents put him so far beyond the pale that in all my life I’ve met him only twice, the second time at my mother’s funeral.

My parents replaced religion with a belief in reason and beauty. I suppose I shouldn’t say “belief,” because belief is, or can be, irrational. Perhaps I shouldn’t even say “replaced,” because that suggests they saw religion as an empty space that needed filling. But neither of my parents arrived at atheism by way of reaction. Instead, it was the frank realization of a secularizing tendency that had worked its way through generations of their respective families.

Atheism united them, but they differed in the backward-looking perspectives that underlay their shared nonbelief. My mother saw religion as a cultural artifact to be preserved by the enlightened generations that had evolved beyond it. My father, a rationalist and a universalist, regarded his Judaism as simply beside the point. Their separate attitudes reflected their personal differences, but also a famous asymmetry between the two religions. Christianity has a lot to preserve. Architecture, sacred art and music, the folk customs that have grown out of it over the centuries: these are just some of the items in the inventory of its great estate. Judaism has its own material culture, of course, but it carries far less baggage than Christianity. In its essence, it’s about the word and the book, and is thus more portable.

“When we don’t go to church,” the old joke goes, “we don’t go to the Episcopal church.” My parents’ versions of disbelief carried different flavors. My mother’s was infused with affection and nostalgia, like a delicate tisane, whereas my father’s characteristic exasperation gave his dismissiveness a distinctive pungency, like hoppy beer. But once again, the situation was not symmetrical. Belief is commonly considered more essential to Christianity than it is to Judaism. A Christian’s sense of identity is tied up in it, or at least that used to be true. But Judaism has no catechism. An unbelieving Jew will remain a Jew by virtue of having been born one. There was nothing my father could do, short of conversion—perhaps not even that—to escape his identity, and much that he did inadvertently reinforced it. His devotion to thinking and reading was itself an element of his Jewishness, or so I later realized. Even though his text was not Torah but John Maynard Keynes, he spent his days in study, and that was a quintessentially Jewish occupation.

Except in connection with her duties as president of the local chapter of the League of Women Voters, my mother never attended church, and if there had been a synagogue in Williamstown, my father would never have set foot in it. Likewise, our family never observed the Jewish holidays or lit Sabbath candles. But there the nevers end, because we did celebrate Christmas, which was my mother’s production and a major event. We three children sprayed pine cones with gold and silver paint and glued cotton beards on walnuts to make Santas. My mother sat at the piano banging out “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear” and “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” from the Fireside Book of Folk Songs while we sang along full-heartedly. She played hymns as well, including “A Mighty Fortress,” that supremely affirmative anthem of Protestantism, suitable for bellowing out at the top of one’s lungs. I wonder: How did she expect us to sing that song in a secular spirit? It was like being spoon-fed, then forbidden to swallow.

On the last day of November, she handed out advent calendars. To pry open one stiff little cardboard door each December morning, finding within it the image of a symbolic favor—a glowing star, perhaps, or a rose blooming in snow—was a purer pleasure than unwrapping presents on the 25th, when all the calendar doors hung ajar and only the emptiness of Christmas afternoon awaited us.

At Easter my mother baked a cake in the shape of a lamb, and we children dyed eggs and hunted for jellybeans. I have an early memory of a bunch of daffodils in a glass vase at the center of her holiday dinner table: from my low vantage point their dark swollen stems, diagonally crossed beneath the water line, seemed more to the point than their trumpet-shaped blossoms. Even though we had only a muddled idea of Easter’s significance, we understood that for all its bunnies and bonnets, it was not as easily secularized as Christmas. We knew enough to be made uneasy by that holiday’s association of Christ’s death agonies with the tender renewals of spring.

Beauty was everything to my mother. For my brother and sister and me, Christmas and Easter were occasions of great joy, but she made it clear that we were celebrating these holidays in a purely aesthetic spirit. We were not to believe. Belief was an error, an embarrassment, “tiresome,” as she would have put it. She meant her gifts to stay wrapped in memory, not to be ripped open to reveal their meaning. To use them in the service of religious enthusiasm would amount to a kind of desecration, a violation of her canons of taste.

But perversely enough, I wanted to believe, or at least to know what belief meant. I thought I saw shapes moving behind the curtain of ritual, but was never quite able to make them out. For a while at age seven, I attended the local Congregational church by myself, hoping for a revelation. My father rolled his eyes at my folly, but my mother kept a poker face. She knew my interest wouldn’t last, and it didn’t. I had imagined standing among the adults in the pews, listening, but instead I was immediately placed in Sunday school, where the class collaborated on a mural of Children Around the World, painted in watercolors on brown butcher paper. My inchoate theological questions found no answers.

About my father’s background we knew almost nothing. He was too busy marking blue books and running the political campaigns of local Democrats to tell us much; he left these matters to my mother. The only clue he gave us—and I didn’t see its cultural significance until much later—was his hobby of pickling Kirby cucumbers from my mother’s garden. He kept them soaking in brine in a ceramic vat in the chilly pantry behind our kitchen. We ate a few while they were still half-processed and crisp; the rest stayed submerged until they were authentically limp and semitranslucent when sliced into spears, indistinguishable, I’d later discover, from the pickles served at Katz’s in New York.

The little we learned about Jewish culture was conveyed to us not by my father but by our philosemitic and highly literary mother, who read aloud from Leo Rosten’s The Education of

H*Y*M*A*N K*A*P*L*A*N. We all loved those tales of that heroic immigrant from Kiev, enrolled in Mr. Parkhill’s class at the American Night Preparatory School for Adults. I don’t own the book anymore—it’s been 60 years—but I remember by heart two of Hyman Kaplan’s devastating bits of doggerel about his classmates:

Mrs. Moskowitz

By her it doesnt fits

A dress—Size 44.

And—a masterpiece of literary economy:

Bloom, Bloom

Go out the room!

My mother read those lines in a creditable Yiddish accent. We knew they were funny and laughed accordingly, but for us Hyman Kaplan occupied the same faraway fictional universe as Ferdinand the Bull, lying under his cork tree in Seville. If she was using the book to teach us about our paternal heritage, it was a failed lesson, because how could Hyman Kaplan, with his marvelously revealing broken English, bear any relation to our gracefully assimilated father, with his years at Oxford and his knowledge of wine vintages?

I realize now that there was anti-Semitism in the Williamstown of the 1950s, even beyond that of the college president. Jews were not welcome in the Williams College fraternities in those days, and certainly some of the brothers—the ones who urinated out of windows and stuffed cats into washing machines—had just the attitudes one would expect. A certain venerable men’s clothing store (which outfitted one of Bing Crosby’s sons, newly arrived from California and shivering in a madras jacket) was a bastion of contempt for Jews and Catholics and anyone else not classifiable as WASP. We children were hardly aware of bias against Jews. How could we be, when we hardly knew what it was to be Jewish?

And how was it that we never learned about the death camps? In 1959, we were only 14 years past the liberation of Auschwitz. Our parents and teachers wouldn’t have kept it from us deliberately. I suppose one explanation might be that the Holocaust hadn’t yet come into full historical focus. Even so, it seems odd that there was nothing in the tone of the time to suggest that the catastrophe had happened at all. The postwar period was a particularly hopeful era, a time when a gifted second-generation Jewish academic like my father could find himself called to Washington by the newly inaugurated president.

When I was 12, my family moved to New York City, where my father went to work for the Ford Foundation. We were there for only six months before the call came from Kennedy, but during our Manhattan interval I learned more about the Jewish world. I got to know some of my father’s relatives, particularly my great-aunt Helen, who operated a kind of family salon in her small high-rise apartment near Columbus Circle.

At that age, I was hard to have around. It must have come as a guilty relief to my mother to put me on the bus after school and send me to Helen’s, where I was fed on demand and made much of by the crew gathered there. I remember some of them, like my great-uncle Abie (who was—exotically enough—a bookie), quite well. Others were elderly second and third cousins whom I could never keep straight. But it hardly mattered which batch of relatives happened to be parked on Helen’s couch on any given afternoon; I always got the same wildly enthusiastic reception. Never before had so many faces been thrust into mine; never before had I been so insistently kissed and hugged and taken aside to be quizzed about my life. Such kind people! At that unhappy time in my life, they rescued me. I was a fat, awkward preadolescent, failing in school, so their kvelling was necessarily limited in scope. Nevertheless, I was praised for my “charm,” my vocabulary, and my hair, which was said to be as full of golden glints as the Breck Girl’s. I resisted this attention, squirmed and giggled and tried to edge away as children do when they’re fussed over, but even then I knew how much I needed it. The memory of those afternoons at Helen’s has warmed me ever since, like a heated stone in my pocket.

And later on—unlike either of my siblings—I married a Jew. My husband’s parents were refugees from Hitler’s Germany, tense, uncertain people very unlike my own self-assured parents and also quite different from my haimish, demonstrative New York relatives. By the time I met them, they were wealthy and well dressed, but still displaced persons, forever carrying with them the troubled air of Europe. From them I gained a new, firsthand understanding of the Holocaust. My husband’s father had lost his sister to the camps, and his mother had lost her parents. Both of them came to the United States haunted by grief and terror. They threw themselves into the project of establishing themselves here with an extraordinary energy—as if to save their lives and the lives of all their descendants.

Early in my marriage, I attached my filial feelings, which I’d long since withdrawn from my own parents, to my husband’s. I loved them for the dangers they had passed; knowing them has made me painfully alert to the anti-Semitism that has been steadily reconstituting itself over the past 60 years. They accepted me in spite of my status as a half Jew, but when I became pregnant, my father-in-law prevailed on me to convert. This was necessary because the Halachic law of descent is matrilineal. It recognizes half Jews whose fathers are Gentiles, but not the half-Jewish children of Gentile mothers.

I had doubts about conversion, but I wanted to please my parents-in-law too much to admit them to myself. They had doubts too, though they hid them. My husband, who at that stage of his life was as impatient with religion as my father had been, wanted no part of the enterprise. Even the rabbi was doubtful. Judaism itself, I couldn’t help observing, is deeply ambivalent about conversion. It does not reach out to embrace the convert, but allows itself, rather reluctantly, to be embraced. Why else would the conversion process call for three ritual discouragements? Even so, I fulfilled all the rabbi’s requirements except for the postpartum ritual bath, the mikveh, which I put off for so long that I was embarrassed to return to his office. The conversion failed, but in the end it hardly mattered. My daughter’s birth made me a member of the family, if not a member of the Tribe. Since then, I’ve lived in a Jewish world as a resident alien, a partisan but not a citizen.

I’m 72 now, in the midst of one of those reappraisals that seem to be the task of late life. Like my parents, I’m a lifelong atheist. I arrived at disbelief not through an exercise of reason—though I did do that—but because it was passed on to me as a family tradition. That’s what made it stick, just as baptism sticks to a Baptist and Zoroastrianism to a Zoroastrian. It’s atheism by default, far less confident than my parents’ blithe and cheeky version, but seemingly inalienable. My atheism doesn’t mean, however, that I’m done with religion. Is anyone ever? Atheism doesn’t eradicate it, only covers it, like a lost city—in my case two lost cities—buried under a mound of earth. I’m no more done with religion than I’m done with my parents, from whom I was estranged all my adult life and who have been dead for decades. Somehow I’ve managed to preserve inside myself the two religions in which they didn’t believe—and in which I don’t believe either—and to maintain these negatives in a precarious balance.

Friends have suggested that I make the most of my double heritage. Why not take advantage of the riches of both religions? Why not be both Christian and Jew? I know other half Jews who manage to do this, but I find I can’t light the menorah even as I decorate the tree. Perhaps it’s my mother’s aesthetic influence: she wouldn’t mix her metaphors that way. But I should give myself credit; in spite of my godless upbringing, I aspire to a certain seriousness about religion. To identify myself as both Christian and Jewish would be to acknowledge that faith is only a set of cultural practices, and even though I don’t believe, I want belief to be possible. Because I can’t be both; I can only be neither. That’s the tribute that my atheism pays to religion.

I must confess that in recent years I’ve developed a hankering for Christianity that threatens to upset this equilibrium. No doubt it has to do with age and the approach of the end of things. When I lift my eyes to the vaulted ceiling of a cathedral or listen to a Bach cantata, I feel a spiritual dilation. And when I sit at the dinner table of churchgoing friends who say grace, I feel like an anthropologist who has been studying a remote tribe and finds herself unexpectedly included in an arcane rite. I’m agog to observe that my neighbor Dave is talking to God, thanking him for the lasagna we’re about to eat.

Saying grace amounts only to the perfunctory mumbling of a few words, but the other people at the table would be amazed to know what a storm of contradictory feelings it raises in me. If their heads weren’t bowed, they’d see that my eyes have welled up, but also that I’m smirking. My scorn is all too familiar a reaction—it’s bred in the bone—but I’m also moved to tears by gratitude. The fact is, I envy Christians. I envy them the consolatory benefits to which their religion entitles them. Fellowship, for example: what would it be like to belong to a community in which everyone accepted me in spite of my sins—not in spite of, because? How would it feel to know that people pray for me?

I envy Christians their holidays, not just Christmas and Easter, but all the obscure feasts, remembrances, and days of repentance that mark the liturgical calendar. For an atheist the year is rather trackless. I envy them the narrative of Christ’s birth, death, and resurrection, but more than that, I envy the smaller narratives that religion imposes on every Christian life. How absorbing, how suspenseful it would be to move through hours, days, and years with the conviction that what I do matters, that my small choices and responses to contingencies have moral meaning, that they will add up to a whole and that my life will be judged.

I envy these things, but I know quite well that I wouldn’t last long as a Christian. Fellowship would soon turn suffocating, and how could I, who can no more pray than fly, pray for the people who pray for me? And while I might long for my life to be shaped by religion, I’m incapable of the belief that is a requirement for that privilege. The best I can do without it is to live by a godless code of ethics, and to accept the discouraging fact that nobody is keeping score.

My understanding of Christianity remains primitive and unevolved. For me, it’s a glittering cargo cult, centered on a few remembered tokens, the repository of those transcendent, quasi-mystical sensations that are most intense in childhood. I’m really no more sophisticated about it than I was at age seven, when I presented myself at the Congregational church to be initiated into its mysteries.

On insomniac nights, I bring to mind the folkloric Mexican crèche that it was my job to lay out on a mirrored tray every Christmas Eve. I remember the kneeling kine and the donkey and a cluster of rough-hewn figures representing townspeople, the men with their knees bent in supplication and their arms thrown up in benediction, the women curtseying deeply. I remember the Three Kings, each carrying a rough bundle to represent his gift of gold, frankincense, or myrrh. I remember the out-of-scale heroic angel, half-martial, half-maternal, presiding at the head of the cradle, her great wings unfurled. I can picture the lowered eyes and rosebud mouths of Mary and Joseph. How delicately their faces are painted, eyelashes individually rendered and cheeks glowing as if from within. But the infant Christ himself, lying on a tiny pallet of real straw, is shockingly rudimentary, nothing more than an armless, legless grub.

If I were to take a religious turn, it would be toward Christianity. But strait is the gate and narrow is the way. In order to pass through, I’d have to shrink myself to the size of the child I was before I knew better than to believe. How would I do that, and what would be left of me?