Anatomy of a Collision

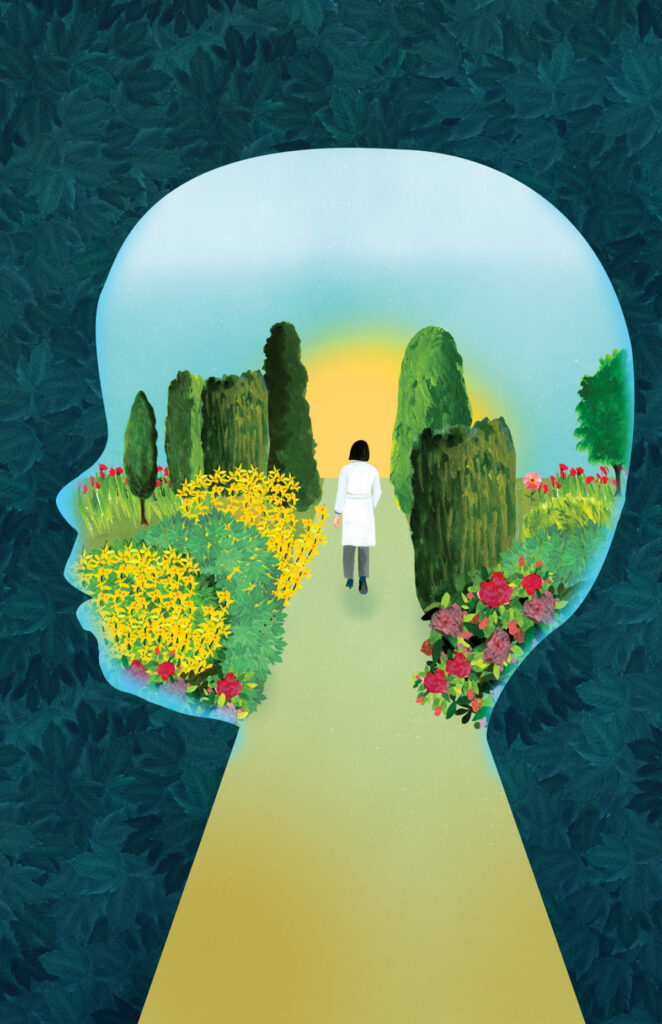

The sudden intersection of one’s professional and parental identities can lead to a strange kind of work-life imbalance

When children arrive, nothing from our old lives is sacred anymore. Not sleep and not sex, not furniture arrangements or retirement plans or long-settled agreements about who washes dishes and who folds laundry.

And then, as our children grow into themselves, the disruption can feel weirdly personal. Bookworms find themselves raising budding athletes. Sworn night owls have a brood of early risers. Hog farmers land an indignant vegan. In the calm of night, we envision who our children will become and who we will become on their behalf, but we plan and God laughs. Sometimes, God has a field day.

Seven years ago, I was an expert. I had a PhD in cognitive psychology, a postdoc in child development, and several scholarly publications under my belt. I studied how people of all ages learn and process information, particularly language. For three years, I wrote about what I studied in a weekly column for this magazine’s website. Eventually, I moved full-time into science communication, taking a job at Northwestern University as editor-in-chief of a magazine that translates academic research into articles for a general audience.

When I became pregnant with my first child, I recognized that I had a lot to learn about being a parent—namely, everything. But what I did know was the science of child development: the big debates among researchers, the hallmark studies and shiny new findings that shaped current thinking. I assumed that when questions of my own cropped up, I’d know where to turn for answers. I even envisioned leaning into my identity as a scientist-turned-writer-turned-new-mom, peppering future work with my daughter’s earliest words and charming misunderstandings as she inevitably and adorably did all the things that babies do, each at the developmentally appropriate time.

Then, at a routine checkup, our pediatrician handed my six-month-old a small block. It slipped through her fingers as if it had no weight at all. As the doctor explained, and as a host of specialists and evaluations would confirm, almost no area of her development was “on track.” She appeared to be nowhere near the track. If every other six-month-old was on a direct train to Topeka, we were driving around the suburbs of Indianapolis, unsure how long we’d be out or whether we’d ever get home again.

I knew, going into that appointment, that my daughter was a late bloomer. A very late bloomer. But I also knew that development is notoriously variable, and that most kids do eventually get to Topeka, on their own route and timetable. Children are astonishingly innovative and resilient learners. The literature is full of studies that demonstrate how well equipped they are at shockingly young ages to help someone solve a problem (14 months!), intuit that others can hold false beliefs (13 months!), assign meanings to nouns like banana (six to nine months!), or recognize familiar speech patterns (while still in the womb!). Read enough studies and you’ll get the impression that babies are like tabletop wind-up toys, born ready to unspool into walking, talking, Red Rover–playing kindergartners. To raise them right, all we really have to do is keep them from falling off the table.

So the doctors’ and specialists’ concerns, written in stark paragraphs and accompanied by percentiles so low that they appeared mathematically dubious, knocked me flat. If babies accumulate milestones as easily as they do months, why did my daughter need six kinds of therapies? I frantically calculated how I’d get both of us back on track: if she worked hard enough, and if I worked hard enough, we’d be on familiar ground soon enough.

Desperate, I found myself acquiring objects my previous self would have dismissed as gratuitous, even shameless in their appeals to parental anxiety: gadgets that blinked and beeped (to hold her attention), a pegboard with stackable dowels (for fine motor skills), a trampoline (for gross motor skills and balance), fish oil (for brain development), an electric toothbrush (to “wake up” the mouth), and a set of secondhand language-learning flashcards for the extremely discounted price of $100. For several bewildering months, I even subscribed to Gemiini, a provider of online videos that teach language skills. The videos featured short clips of different speakers saying the same thing over and over, sometimes at a normal rate, sometimes slowed down, sometimes embedded in a sentence, sometimes with the camera zoomed in tight on the lips. They had a trippy, surrealist quality. “Happy. Happy. I feel happy. I feel happy. I am happy. Haaaa-pppppy.” My daughter was intrigued.

But the company’s marketing didn’t just tap into parental anxiety; it seemed singularly dedicated to stoking it into something all-consuming. “Regret will tear you apart as a parent,” read a post on the company’s blog:

How will you feel if you knew you could have made a difference in your child’s life, but you quit after a few months, when a breakthrough could have been two years away? It could be the difference of a life where others make decisions for your child, or a life of independence. We don’t want thousands of parents, years from now, going to bed every night with regret wondering “what might have been” if they had persevered with Gemiini.

Had I really become a person who would read that manipulative heap of a post and still type in my credit card number?

It’s not that I was a bad expert, I realized. It’s not that I couldn’t interpret the studies I was reading. It’s not even that all those studies were wrong—as I confirmed after the birth of my second child, who could’ve hit her developmental milestones under the tutelage of a pack of friendly dogs. What I was, though, was the wrong expert for the moment. In nearly every study I could think of, my daughter would have been tossed from analysis as an outlier. There were limits to my knowledge, limits that didn’t seem important until I slammed into them headfirst. Suddenly they were all that mattered. The realization was painful and slightly shocking, like learning that someone you’ve long admired actually dislikes you.

Friends and family would comment on how fortunate I was to have the background I did, and how much my daughter was sure to benefit from my expertise. I began to believe the opposite: that I was uniquely ill prepared to be the mother she needed, and that my supposed expertise could just go to hell.

I am not the first, of course, to experience an uncanny collision between my parental and professional identities.

Shashank Sirsi, an associate professor in the department of bioengineering at the University of Texas at Dallas, researches neuroblastoma. This cancer’s name often makes people think of the brain, though it begins most commonly in the adrenal gland before spreading to other areas of the body. “Technically, it can at times present in the brain,” he says. “But it’s very rare.”

For many years, Sirsi only barely identified as a cancer researcher. He is an engineer: someone who builds things. His lab develops novel ways of targeting drugs directly to neuroblastoma tumor sites. If drugs are more precisely targeted, patients will need fewer of them, which in turn means fewer side effects. A common chemotherapy drug like doxorubicin “is very effective at destroying cancer cells,” Sirsi says, but it “also destroys the heart.” Side effects can be particularly devastating for children—those who survive cancer have more years left to live than adults do and experience more prolonged suffering as a result. This is why Sirsi chose to focus his work on this younger population.

Then in 2020, his wife, a pediatrician, noticed a lump on the abdomen of the couple’s three-month-old son. It was neuroblastoma.

The collision of Sirsi’s lives as a researcher and as a father was cause for a strange sort of professional reunion. “Neuroblastoma is a very rare disease,” he says. “So everybody in the field knows everybody.” A collaborator on a recent grant helped his son get admitted to the hospital; eventually, his son switched over to the care of a former student of another collaborator’s colleague. The web of connections became a “really big source of comfort” in the midst of a scary time—as were the upbeat predictions about how his son would fare in treatment. These predictions were spot on: after just two cycles of chemotherapy, his son’s tumors shrank by 75 percent, and his current prognosis is excellent.

But experiencing neuroblastoma in this new, devastatingly personal sense felt “like more than coincidence,” Sirsi says. He felt embarrassed, even guilty, that he’d never before considered how onerous it is for families to coordinate the care they need from the various specialists they are expected to frequent. Or even that there are so many specialists to see.

This insight has seeped into Sirsi’s latest work. Plotting out a convoluted treatment plan on a chalkboard is one thing; expecting families to follow it is another. A current project uses augmented reality to help doctors better pinpoint metastatic disease in patients who are being treated at the same time with focused ultrasound—essentially saving patients and their families a step. “I can see how some parents or patients would just throw up their hands and give up if they have to keep on coming back to a clinic every day,” Sirsi says. He is now trying to simplify that process by designing a device, for instance, that would allow this new procedure to occur simultaneously with other forms of treatment.

When I ask Sirsi whether the collision of his identities ever felt like too much, he is adamant that it did not. “If anything, it motivated me to sit down with my lab and say, ‘This is the direction we’re going to go,’ ” he says. “This is the universe kicking me in the ass and saying, ‘Get off the chalkboard and start helping patients.’ ” These days, the content of his conference slides hasn’t changed much, but the framing is different: he’s no longer presenting on the mechanics of targeted drug delivery. He’s talking about therapy for children with neuroblastoma.

The odds that a story like Sirsi’s would happen seem minuscule. Yet for all its bizarre particulars, similar tales abound. There’s A. Thomas McLellan, an addiction scholar who loses a son to a drug overdose and then develops a consumer guide for assessing adolescent treatment facilities. There’s the developmental biologist Soo-Kyung Lee, who studies a rare gene family and gives birth to a daughter with a related gene mutation, a mutation that she now researches full time. There’s the rehabilitation engineer James Sulzer, whose three-year-old experiences a traumatic brain injury after being struck by a tree branch and who finds his child on the receiving end of the kinds of therapies and technological interventions he has spent his career developing.

Some are tales of gentle comeuppance, like that of the screen-time expert Anya Kamenetz, whose advice to parents about monitoring “the nine signs of tech overuse” in kids undergoes a pandemic-induced tone shift after Covid-19 wipes out her usual childcare arrangement. But most collisions promise something deeper: rare insights of the sort that can be gleaned only by traveling a winding path first as an expert, then as someone stripped of all credentials—unmoored and terrified—and then yet again, precariously empowered, scanning the horizon for a better route.

Natalia (whose name has been changed to protect her privacy) is a pediatrician at a large American hospital, which means she sees more children with severe medical complexities than most pediatricians do. Perhaps that’s why she spent so much of her pregnancy worried about giving birth prematurely. Her daughter arrived full term, but almost immediately, she had some concerns. “I held her in the nursery and remember feeling like she was too stiff,” she tells me now. At six weeks, her daughter seemed stronger in one side of her body than another. At three months, she was still missing a protective reflex—the mechanism by which parts of our bodies recoil from potentially harmful stimuli. She wasn’t gaining weight.

As Natalia’s concerns mounted, part of her—the high-achieving parent who wanted to feel in control and have a plan—was inclined to immediately demand every available diagnostic test. But ultimately, she turned the diagnostic process over to trusted colleagues. When the results from a genetic test came back, she finally had her answer: a point mutation on one of the many genes that help neurons communicate. Variations to this gene are associated with a host of developmental and medical challenges, including intellectual disability and hypotonia, a condition in which a patient’s muscle tone is diminished; in severe forms, it can affect sucking and swallowing. Her daughter wouldn’t suffer a physically painful childhood, but the life of independence Natalia had envisioned for her would never come to fruition. “I was so relieved and so sad at the same time,” she says.

When I ask how parenting her daughter, now six, has changed her as a pediatrician, Natalia has a very different take from Sirsi. For the most part, things hadn’t changed at all: she had initially gone into pediatrics “to be a fierce advocate for patients,” and in this respect, her experience as a mother simply affirmed her approach, especially in regard to her bedside manner.

Occasionally, she will mention her daughter to patients and their families. To a parent who dismisses a state-supported early intervention program as a government handout, for instance, she might say that her own daughter had benefited greatly from that very program. Or to the parents who hesitate to vaccinate a child with a genetic disorder, for fear the vaccine will interact in unforeseen ways with their child’s unique DNA, she will explain that her daughter also has a genetic disorder, and she chose to vaccinate. “But you have to be super careful about it, because it’s not about you,” she says. Only a few long-time patient families, now something closer to friends, know more of her daughter’s story.

If the way Natalia practices medicine hasn’t changed dramatically, the collision’s toll on her well-being has been more complicated. A few years ago, when she decided to move to a new neighborhood so that her daughter could receive superior special education services, she considered a house near her work. But as a pediatrician for high-risk kids—kids in pain, kids who do occasionally die—she couldn’t bear the thought of recognizing those very patients in her daughter’s classroom. She moved elsewhere.

And though her medical training is an asset when it comes to navigating her daughter’s disability, she has also felt the weight of parents’ expectations. Against her wishes, she was introduced to a parent who’d founded an advocacy group devoted to the rare syndrome that both of their children shared. “I remember her saying to me, ‘We’ve been waiting. We’ve been waiting every day for you to call us,’ ” Natalia says. “I told her I am not this savior that’s going to come in and fix this for our kids.”

The very idea of a fix rubs Natalia the wrong way. Many parents in the advocacy group are pushing for a cure—something she views as both medically impractical and a waste of resources better directed to patients with preventable diseases, deadly diseases, and diseases for which everyday pain could be reduced. Natalia’s daughter, unlike a lot of her patients, is happy. And though society may not quite see it this way, “in the grand scheme of how people are doing,” Natalia says, “she’s actually okay.”

Today, Natalia declines to see children with her daughter’s syndrome, which isn’t always easy. Once, when scrolling through a syndrome-related Facebook group, she saw her name on the feed. One parent was looking for a new pediatrician, and another mentioned Natalia as a possibility. So she messaged the woman privately: stop by for a glass of wine sometime, she urged. Just don’t come to me as a patient.

She eventually referred the woman to another pediatrician. But recently, that colleague went on leave. “And guess who shows up on my schedule?” Natalia sighs. “It’s just so hard. I know she’s just trying to get by like the rest of us.”

Jonathan Adler, a professor of psychology at Olin College, has never studied collision stories like Sirsi’s, or Natalia’s, or mine. To his knowledge, nobody has. But he has spent a lot of time investigating how identity develops over time, how we craft an evolving story about ourselves so as to ascribe meaning to our lives. The more coherent our story is—that is, the more our own journey makes sense to us—the more secure we feel in our identities.

For the most part, we are pretty good at tweaking and expanding our sense of self to accommodate the messiness of life. Getting divorced, being fired: these can be life-altering events, but they don’t necessarily have to be identity altering. “People can spin those into whatever kind of story they need to support who they are,” Adler says.

But some events aren’t integrated so easily: dramatic changes in physical function from a severe chronic illness, for instance, or an acquired disability. “They offer this discrete and inescapable moment of disintegration,” he says. “When something happens to your body, you can’t just ‘story’ it away. It’s an unavoidable, inescapable constraint on identity where you have to figure out who you are.” He suspects that at times, parenting collisions can offer similarly stark moments of disintegration. Imagine, he says: “Your entire life in one role. And then something happens that flips that role in a very particular way.”

It isn’t uncommon for parenting and professional lives to intersect. A physician may serve as a medical adviser for her child’s school district—something we’ve seen plenty of during the pandemic—or a social scientist may pivot to criminal justice reform after his child’s tangle with the legal system. Indeed, an early transformative personal experience with a medical or social issue can be what leads someone to become a doctor or a social scientist in the first place. But that is a choice, generally speaking, a conscious decision meant to bridge the gap between one’s personal passions and professional aspirations.

Collisions can be more disruptive, as if the fabric of our being has caught on a nail and no amount of wiggling will get it unstuck.

In his book Far From the Tree, psychologist and journalist Andrew Solomon distinguishes between the “vertical identities” that children inherit from their parents, such as ethnicity or language, and the “horizontal identities”—the “recessive genes, random mutations, prenatal influences, or values and preferences”—that they do not. The distinction is helpful when considering how parents, experts or otherwise, interpret a child’s diagnosis. None of us wants to see our child ostracized or in pain, or brushing shoulders with death, but some parents, by virtue of their own diagnostic histories, are better prepared to make sense of the situation and to imagine what a good life can look like. Parents who share some disabilities with their children—deafness, dwarfism—may not view them as disabilities at all, but as meaningful identities, tied to a rich and affirming culture. Perhaps this is one reason why Moyna Talcer’s parenting collision unfolded so differently from mine.

New motherhood is always a drubbing of feelings and sensations, but for Talcer, who lives in England, the intensity of those sensations was startling. It began during pregnancy, when she developed a severe form of morning sickness. Sometimes she would vomit as many as 25 times a day. The smell of her own skin got to her. “I want to be clear—I did wash it!” she says. “But I was so sensitive that any smell that I perceived was just overwhelming.”

When she gave birth to her son, the nausea stopped, but not the feeling that her senses were in overdrive. The constant touching. The constant need for vigilance lest something, anything, happen. And the screaming. Her son had colic, and the sound of his cries regularly put her on the edge of panic. Knowing that these visceral experiences were outside the norm, she tested herself for a variety of conditions, like postpartum depression. But nothing fit.

A diagnosis, when it came, was a relief: autism. Talcer had felt since childhood that she wasn’t quite like everyone else—that she was standing on the outside of social settings, looking in. Over the years, she’d been diagnosed with dyslexia and then dyspraxia, a neurological disorder that affects coordination skills. She’d spent the previous 15 years as an occupational therapist for the National Health Service, where she worked regularly with autistic children and teenagers. Her clients and their families often remarked that she seemed to “get” them at an intuitive level. The knowledge that she, too, was autistic helped her own story make more sense.

She was, however, nervous about disclosing her diagnosis to others. Talcer was particularly concerned about what her fellow health care professionals might think. Would they judge her? Dismiss her? The issue came to a head when she decided to conduct a research project on the sensory experiences of autistic mothers—her effort to bolster a depressingly anemic literature. After conferring with a few trusted researchers and professionals who’d similarly “outed” themselves as autistic, she decided to mention her own diagnosis in the published study.

To her delight, the disclosure has been a boon for her professional career, connecting her to other autistic scholars and opening new avenues of research. She has found it energizing to join this growing body of passionate researchers putting their mark on our understanding of autism. “If you’ve got neurotypical people talking about autistic needs and research, you need to have the autistic perspective,” says Talcer. “I don’t see how you can have a conversation without autistic people involved.” She points to the work of autistic scholar Damian Milton, who has proposed the “double-empathy problem.” For Milton, communication difficulties attributed to autism are better understood as challenges facing both autistic and nonautistic people in their interactions with one another. Nonautistic researchers, steeped in a view that sees autism solely as a set of flaws rather than differences, tend to assign responsibility for these mishaps solely to the autistic person.

A few years later, when her son was also diagnosed as autistic, Talcer took it in stride. She felt confident that she could support him in any way he needed—not that it has been easy juggling dual roles as occupational therapist and parent for her son. “You never know if you’ve got the balance right,” she says. “But I think if he’s happy and engaged, and he’s able to function in a way that doesn’t cause him anxiety and stress, I would say I’m probably doing it right.” She provides him with “visual schedules” (sequences of pictures that allow him to see how his day will proceed), and she hands him a stick of chewing gum to provide sensory input as he transitions between home and school—the kinds of things she’d do for her clients.

Talcer’s unlikely parenting saga has changed her as a therapist, too—particularly in how she relates to her clients’ parents. For instance, as she has learned more about the genetic heritability of autism, she’s become aware that, statistically, a few of those parents are likely autistic themselves. So she tries to do things that will feel safe and welcoming to them, too, like offering them choices for how they’d prefer to communicate with her.

As her theoretical understanding of how to parent a child with additional needs gave way to a very real one, she gained a “deeper compassion, a deeper respect” for the families she works with. “Being a mum,” she says, “you learn a whole different way of being.”

For years after my daughter was born, I abandoned all pretense of having anything useful or cogent to say. My days of being an expert were over. Instead, I took copious notes, dull and hopelessly inane notes about non-milestones—data for the strange study that had become my life.

9/12—has learned you have to move your hands to shift the puzzle pieces in

10/13—seems like she is saying “ball” every now and then, but not consistently and we may just be making things up

2/26—was about 90% accurate putting her wooden blocks in one container and her plastic blocks in another

3/14—will try to mimic the different roars of dinosaurs in her book

6/17—still working on jumping, but knows what to do in theory

12/1—understands more than she can show us

I retreated into the scientific literature where I was most at home, sinking deeper into the reference sections that link researchers’ collective knowledge. But despite a wealth of studies, insight was elusive. This is partly because my daughter’s diagnoses, of which she had accumulated many, lacked the clarity and specificity of a genetic difference, and also because research on developmental trajectories, or even the effectiveness of different therapies, is conflicting, incomplete, and often hopelessly outdated.

But mostly because what I wanted was impossible: a scientific study with 30,000 participants—with each participant a version of my daughter, living out a different life in a different possible world. In which of these 30,000 worlds is my daughter happiest and most fulfilled? And what kinds of everyday decisions could we as parents make to help construct that winning world?

Slowly I came to understand that I was seeking solutions to the wrong problem. I watched as my daughter struggled to develop the language and cognitive and motor skills that other children acquire effortlessly. And I watched when, after hundreds of hours of therapy, she correctly pronounced octopus and put together her first puzzle. I watched as the child who couldn’t grasp a block gripped the chains of a swing and taught herself to pump. I gradually released the idea that her life had a trajectory that could be predicted, or that anything but trial and error and a bit more trial and error would help me help her. No study was going to tell me more about my silly, gentle daughter than I could see every morning at the breakfast table, and no therapy was going to get her back on track, because there is no track.

Parenting my daughter is an act of reconciling the nearly irreconcilable. People with intellectual disabilities live in far more poverty, experience more physical and sexual assault, and die more than a decade earlier than other people. I know that this is not okay, and also that my daughter is whole and good. I am aware that the world must change, and I am aware that I am just one imperfect mother, an unraveled expert who occasionally makes absurd, fear-based impulse buys. I brag about my daughter’s accomplishments to relatives on WhatsApp, recognizing also that those accomplishments are completely beside the point. Somehow, knowing all these things feels a lot like knowing nothing at all.

So I turn to a different academic literature. I read about “intellectual humility” to become aware of my own limits. I read about “the quiet ego” to temper my desire to be right and certain. People with quiet egos can see more clearly where others are coming from, engage nondefensively with their arguments, and interpret world-shaking events as opportunities for growth. It’s a personality trait, meaning some people naturally have quieter egos than others, and these folks tend to handle life’s stressors better than most. But at least some research suggests that it can be cultivated by regularly reflecting on its importance.

And I collect collision stories, though this was never a conscious decision. It was more that, once I noticed them, I began to see them everywhere, the way a botanist can spot a pitcher plant from across a bog. They appealed to me not because I expected to be inspired by them or to apply their lessons directly to my life. The takeaways are often as targeted as Sirsi’s drug delivery techniques, the insights both peculiar and bespoke.

I collect collision stories, I suppose, to place my own alongside many others. I am building a library of the unlikely, a place where the strangest twists of fate find their even stranger brethren. I’m arranging an unruly meeting of mastery and doubt, of access to the very best that science can offer and the obligation perhaps to make those offerings better. I am creating space for God to laugh and for others to laugh along with him, haltingly or determinedly or with abandon.