Anne Austin Pearce is an assistant professor at Rockhurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. Here, she discusses her exhibition Leaving Alone, which confronts issues of life and death, nature, and manmade structures.

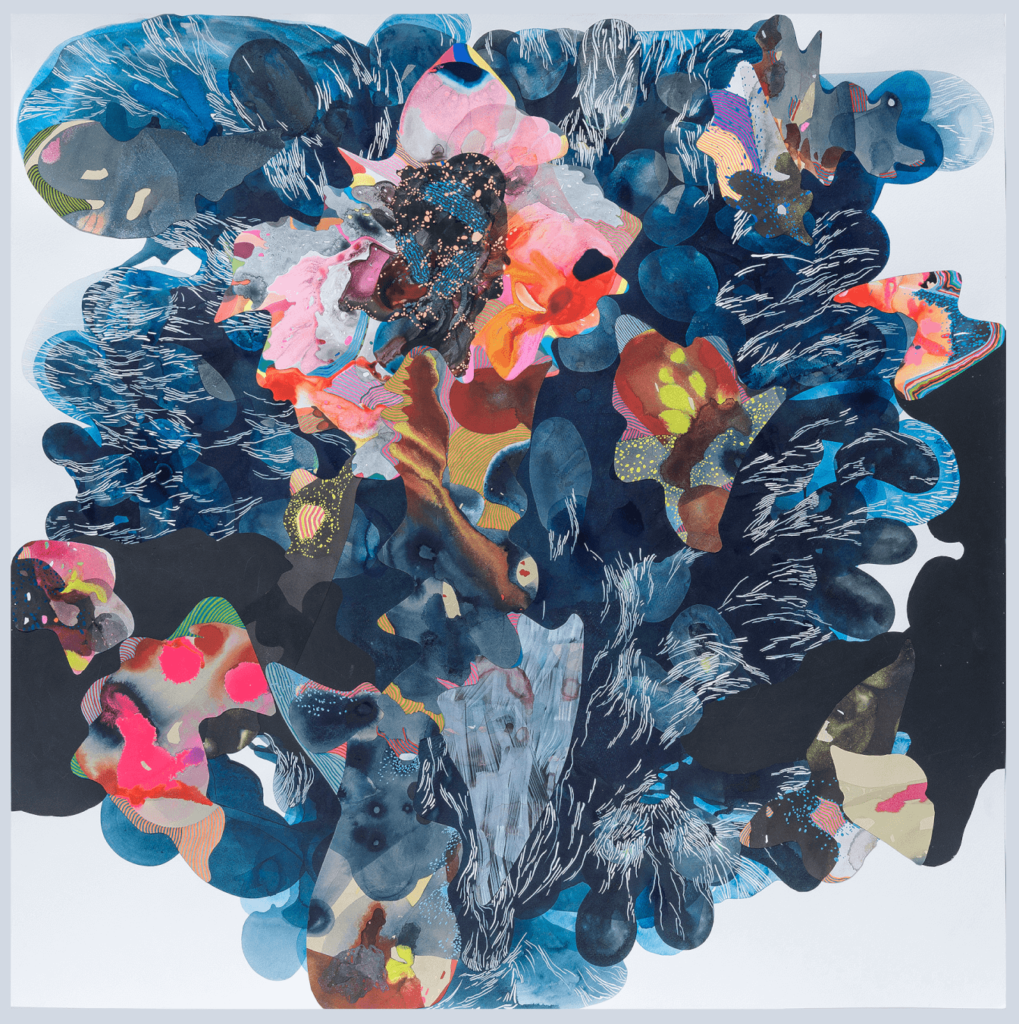

“I work with liquid acrylic, ink, and other mediums on paper. My most recent museum show included sound-video installations and a blown-glass piece. The language that I use is informed by the natural world. I’ve had tremendous opportunity to go to a number of residencies around the world—the immediacy of culture and landscape translates directly into the work that I’m making.

At my exhibition at the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art, titled Leaving Alone, I tied every piece of work to something literary. I had already made four landscapes in response to the death of my father, who passed away when I was seven years old. The landscapes were of the seasons, so in response I made four lnew andscape drawings as a letter to him, and then four different writers wrote responses to those pieces. There was also the moth(er)arium where, over the course of a year, I figured out how to raise moths. It correlates directly to Virginia Woolf’s short essay “The Death of the Moth,” which is so profound in its depiction of the futility of our perpetual attempts to live fully. Not to be a downer, but it’s all part of the cycle of life. The moth(er)arium is a letter to my mother. She was zealous in her attempt to preserve life, which I’m sure was in part a reaction to watching her husband become ill and die. That was the first glass piece that I did.

There is also a poem by Margaret Atwood called “The Animals Reject Their Names and Things Return to Their Origins.” I ended up borrowing 48 recordings of animals from a German museum and making saccharine tubes. The colors reference what we are becoming culturally—we seem to be moving toward unnatural, saturated colors. Inside each tube was a recording of an animal. I created an animal opera—it began with honeybees and it ended with lions. It was cacophonous. You walk into the center of the gallery, and there’s a single stuffed teenage bear that used to belong to the School of the Blind.

Icarus was informed by a poem by Sam Witt, whose “Icarus in Moonlight” that casts the son of Daedalus as a woman. It’s comprised of five years’ worth of drawings. Icarus was meant to mimic an octopus—to completely compress and then reopen. It can all be packed in a pretty small box, technically, and then reopen and be responsive to a new exhibition environment. I want it to occupy a huge space and act as an experience, and then be packed up and contained. It’s an evolving work, I want it to continue to move and shapeshift in other venues.

My big desire is to facilitate the installation of nonintrusive art into natural landscapes. The work becomes bait for humans to reenter nature. I hope that my work serves as a provocation to resume an admiration and care for the natural world. Which hopefully will lead to better decisions. Days and months are subsumed by minutiae. If you can reach the emotive in a human being, then you’ve succeeded.”