As a kid, I loved anthologies, all those fat volumes with titles like The Golden Argosy, Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, Reading I’ve Liked, Ghostly Tales to Be Told, The Omnibus of Crime. Some of these tomes—several ran to 700 or more pages—I would check out from the library and devour, story after story, over the course of the allotted three weeks; others I might discover at a thrift shop and take home for a dime or a quarter and then just dip into from time to time. A few of my relatives had even acquired some of those old Literary Guild and Book-of-the-Month Club volumes, with titles like Stories to Remember or A Treasury of Great Mysteries, each edited by a literary eminence of the day—Clifton Fadiman, Howard Haycraft, Bennett Cerf, John Beecroft, or the novelists Ellery Queen and Thomas B. Costain. I’d borrow these from my cousin Marlene or Aunt Stella, and sometimes I’d give them back.

As a kid, I loved anthologies, all those fat volumes with titles like The Golden Argosy, Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, Reading I’ve Liked, Ghostly Tales to Be Told, The Omnibus of Crime. Some of these tomes—several ran to 700 or more pages—I would check out from the library and devour, story after story, over the course of the allotted three weeks; others I might discover at a thrift shop and take home for a dime or a quarter and then just dip into from time to time. A few of my relatives had even acquired some of those old Literary Guild and Book-of-the-Month Club volumes, with titles like Stories to Remember or A Treasury of Great Mysteries, each edited by a literary eminence of the day—Clifton Fadiman, Howard Haycraft, Bennett Cerf, John Beecroft, or the novelists Ellery Queen and Thomas B. Costain. I’d borrow these from my cousin Marlene or Aunt Stella, and sometimes I’d give them back.

In those days an author’s name meant almost nothing to me. Who were W. W. Jacobs and Ambrose Bierce? Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Richard Connell? E. M. Forster and Anthony Berkeley and Shirley Jackson? I hadn’t a clue. What mattered were those evocative titles: “The Monkey’s Paw,” “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” “The Yellow Wallpaper,” “The Most Dangerous Game,” “The Other Side of the Hedge,” “The Avenging Chance,” “The Lottery.”

So it was that during my adolescence I was gradually introduced to the classics of short fiction, in nearly all the genres. I’ll never forget the first time I read the late Ray Bradbury’s “Zero Hour” in an author’s-choice volume called My Best Science Fiction Story. Bradbury’s wonderful conceit—spoiler alert!—is that aliens secretly persuade children to play a game called Invasion. On the last page a little girl skips lightly up the stairs of her house, followed by the heavier trudge of Something behind her, and opens the door to where her terrified parents are hiding—at which point Bradbury brings this macabre miniature to its perfect and chilling close, as the child murmurs: “Peekaboo.”

Throughout adolescence I sought out all sorts of storytelling showcases. In The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, edited by Robert Silverberg, I first read Cordwainer Smith’s “Scanners Live in Vain”—note, again, that haunting title—and the heartbreaking “Flowers for Algernon” by Daniel Keyes. Those Alfred Hitchcock anthologies called Stories That Scared Even Me and Stories for Late at Night and Stories to be Read with the Door Locked introduced me to myriad chillers and thrillers, including that tour de force of logical deduction, Harry Kemelman’s “The Nine Mile Walk” and Jack Finney’s unnerving “I’m Scared.” (The versatile Finney’s novels include that classic of 1950s paranoia, The Body Snatchers, and THE most romantic of all time travel stories, Time and Again.) In more general anthologies I discovered work by other great practitioners of commercial short fiction: O. Henry, W. Somerset Maugham, Irwin Shaw, and John O’Hara, as well as modern mini-classics by such literary folk as Maupassant, Chekhov, Katherine Mansfield, Frank O’Connor, and John Cheever.

Today, though, I hardly ever pick up an anthology.

At some point, I realized that I had grown more interested in collections, that is, volumes of stories gathering the work of a single author. Rather than read just one of Lord Dunsany’s tall tales about Joseph Jorkens, or one of Robert Aickman’s “strange stories,” or one of P. G. Wodehouse’s misadventures of Jeeves and Wooster, I found that I wanted to read them all. Or at least a lot of them. What attracts me these days aren’t short fiction’s high-spots so much as an individual writer’s overall voice and style, the atmosphere he or she creates on the page. I want to immerse myself in an entire oeuvre rather than flit from one short masterpiece to another.

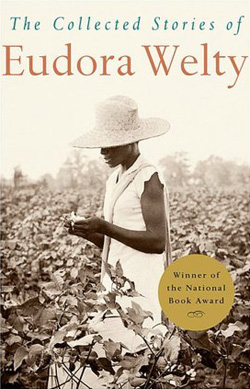

In effect, anthologies are like dating. Through them, you meet a lot of interesting people, enjoy some swell times (mostly) and some awful ones (occasionally), until one happy hour you encounter a story you really, really like and decide to settle down for a while with its author. Of course, this doesn’t lead to strict fidelity, except in the cases of fans who spend their entire lives researching and obsessing about, say, A. Conan Doyle or H. P. Lovecraft. Rather, one adopts a pattern of serial monogamy. Weeks go by or even months, as you read The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty, but inevitably there comes a day when you decide you just can’t face another page about the inhabitants of Morgana, Mississippi, and you find yourself suddenly, irresistibly attracted to J. G. Ballard or Sarah Orne Jewett or Alice Munro. Your friends may shake their heads over the break-up—you were so crazy about “A Worn Path” and “Why I Live at the P. O.”—but still, it’s the modern world, what can you say, these things happen. Besides, more often than not, after a few mad, wonderful weeks or months with X or Y, you’ll find yourself remembering “The Petrified Man” or “No Place for You, My Love,” and then one evening you’ll be standing at Eudora’s front door. This being literature, not life, she’ll take you back without a word.