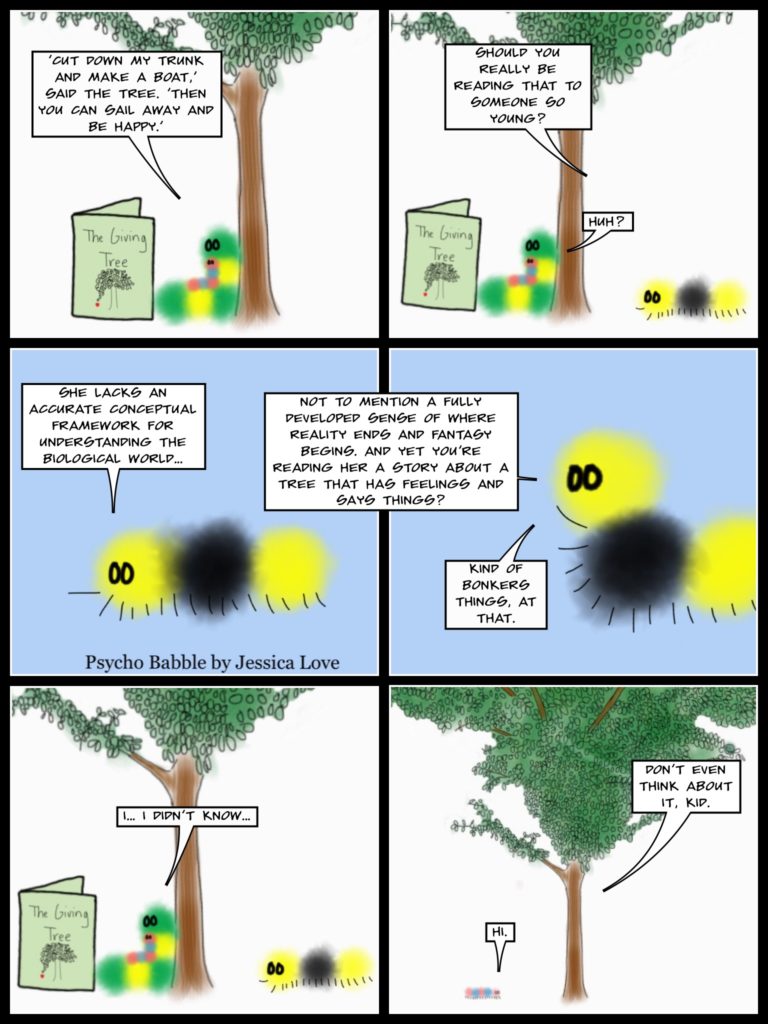

Children and books: What’s not to love? But in recent years, researchers have questioned some of the literary techniques used by authors and educators. Specifically, when the goal of a book is to teach children specific facts—the names of body parts, or how to tell a tomato from an apple, or which animals eat what—fantasy elements, often added to make the stories more engaging, can backfire. The less a story world resembles the real world, it seems, the unlikelier children are to transfer lessons learned from the book to their own lives. And widespread exposure to anthropomorphism poses its own risks. According to University of Toronto professor Patricia Ganea and her collaborators, “The tendency to reason about the biological world from an anthropocentric point of view can have negative consequences for children’s causal biological understanding. For example, research with older children has shown they have more difficulty accurately interpreting evolutionary change when those concepts are presented using anthropomorphic language.”

That said, books are about more than teaching facts, and unless you’re teaching kindergarten biology, the best book to give a child remains the one she’ll read. Later in life, fantasy contexts may even offer thinkers an edge; one 2005 study finds, for instance, that adults with little formal schooling are better able to reason through puzzles containing information that contradicts their everyday experiences when the information is said to be about other planets.