Meetings With Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World by Christopher de Hamel; Penguin Press, 632 pp., $45

Christopher de Hamel is technically a paleographer, someone who studies ancient forms of writing, but that title is woefully inadequate to describe his erudition. He is better referred to as a world-renowned expert on medieval manuscripts, but even that is insufficient. Take this by way of example: when de Hamel puts his hands on the beautiful Codex Amiatinus, the earliest known copy of the Latin Vulgate version of the Catholic Bible (housed in a museum in Florence, and whose origins had been presumed to be Italian but later proved to be English), he can sense the work’s true ancestry by the “curious warm leathery smell to English parchment” compared with “the sharper, cooler scent of Italian skins.”

Yes, as an expert on very old books, he smells them. He also knows what color and type of thread were used in ninth-century French manuscripts, and he tells you, his reader, how the cursive script was exported from Rome and what it looked like in the Merovingian minuscule in France or the Alemannic minuscule in western Germany. He knows where and when variations of the Latin Vulgate were in use, how garnets decorated the covers of sumptuous works from medieval England but never from medieval Ireland. He can point out dates of origin from the heraldry used in 14th-century Navarre. He knows where and when scribes used a sizably rounded-out letter D. He can tell you all about how three-dimensional perspective developed until it became common practice in 15th-century art.

Thousands and thousands of facts, big and little, are stored away in the mind of Christopher de Hamel, but he never forgets that his particular friend of the moment, namely you, knows little about these things. He clears up arcane terminology with casual asides. Almost apologetically, he explains bibliographic practices that have no doubt heretofore irritated and confounded you, providing a clear and simple explanation, for example, of how to interpret: i²,ii-v⁸,vi⁷,vii-x⁸, a series of symbols used by sophisticated bibliographers to describe the pagination sequence of a book.

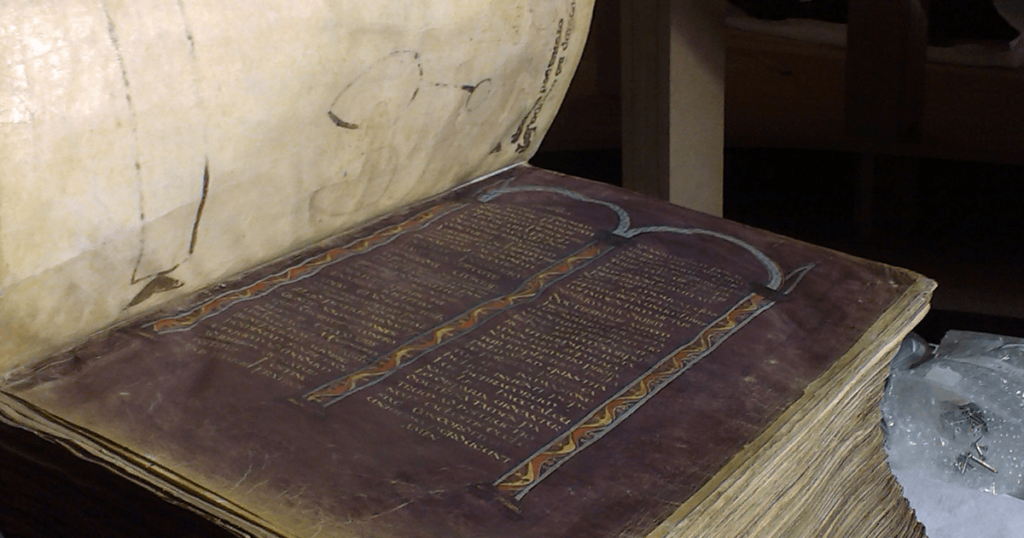

De Hamel takes you on a personal tour of the Western world, from St. Petersburg down through Scandinavia and the Low Countries. You stop off for a while in the British Isles and drop on down to Italy, fly over to New York City, and then out to Los Angeles. You cling lightly onto his raised arm as he leads you across a marble-floored room in a magnificent building, talking all the time, eyes shining. Then you stop in front of an object placed on a table, and he sits you down next to him as he opens the book. He carefully leafs through its pages and begins to speak: wars and festivals, kings and queens, animal skins, inks, holy days, metal clasps, the Annunciation and the Crucifixion, mold stains, the cycles of the stars, the progress of knowledge. Facts tumble out of him as he points and waves his arms about, and it seems he will never slow down. Suddenly he glances over and sees you are glassy eyed, so he pauses, leans back, and relaxes a moment. Then he reaches out and pats the Codex Amiatinus, sitting in its hugeness before you, and reports that it is 1,030 leaves long and weighs 75 pounds (without the binding), and that it took 515 calves to create its parchment pages. There are various legal documents from the region in England where the manuscript originated, supposedly indicating that pasturage was increased because of the specific need for more calves to make more Bibles. De Hamel has his doubts, but apocryphal or not, the story draws you right back in, ready to continue on once again.

De Hamel’s grand book tells you all about 12 magnificent manuscript works. He talks to you about how they look and feel, and the book is sumptuously illustrated to help him along, but you get something extra by looking through his eyes. He points out a little boy scolding his horse down in that corner, some off-duty soldiers playing hoop-and-stick in a tiny image at the bottom of the page, which you wouldn’t have noticed without his directive. He tells you why these manuscripts were created and explains to you the complications, expense, and huge undertaking involved in their manufacture and how they were thus special objects owned only by the very rich, very royal, and very devout. And he tells you about the owners and how they used them. The Book of Kells, The Carmina Burana, The Gospels of Saint Augustine, The Hours of Jeanne de Navarre, The Spinola Hours—titles that you’ve heard mentioned over the years, probably without ever really knowing what they are. You learn all about their composition and construction. De Hamel explains the history behind the ideas printed in these books, ideas that subsequently took root in the collective human consciousness, where they’ve remained as part of our thought for hundreds of years.

You also get a lively history of the manuscripts’ travels through the centuries, involving tales of warfare, conquest, chicanery, theft, and downright incompetence. The Hours of Jeanne de Navarre, for example, was found in an abandoned train car full of stolen art outside Hitler’s Berghof in the Bavarian Alps when the French army arrived in 1945. De Hamel also tells how the scholarly and technical analysis of each work has progressed, the experts’ disagreements and spats, which have at times led to firm and universal conclusions and at others to greater discord and confusion.

Perhaps most important in discussing this magnificent work is to assure you that the overarching erudition is rendered clearly and with great kindness to you, his companion. He shows a shrewd ability in telling you just why this is something you should know. I am a happier and fuller person because this fine man took me on his Grand Tour and told me so many marvelous things.