In our post-Babel (and pre-Cyborg) world, nobody expects to hear a word spoken in an unfamiliar tongue and be able to intuit its meaning. But what about nonverbal vocalizations: the wordless screams and sobs, sighs and exaltations that seem to emerge from us as reflexively as thoughts? Might a rolling laugh or a breathy moan universally indicate amusement or pleasure?

A few years ago, a group of Western researchers led by Disa Sauter headed to Namibia to find out. Members of a group called the Himba—a population of traditional, seminomadic people who’ve had little contact with other cultures over the years—were invited to participate in an experiment: listening to brief stories that evoked a strong emotion and deciding which of two prerecorded human vocalizations best expressed that emotion.

The resulting 2010 study reports that when the vocalizations were elicited by fellow Himba (as opposed to Europeans), they were likelier to make the intended match. Native European-English speakers showed the same increased in-group sensitivity: we’re all better, it seems, at recognizing the cries and sighs of our own people. But crucially, the Himba participants were better than chance at selecting the intended European vocalization, and vice versa. Culture matters, the researchers determined, but some basic vocalizations really do seem universal.

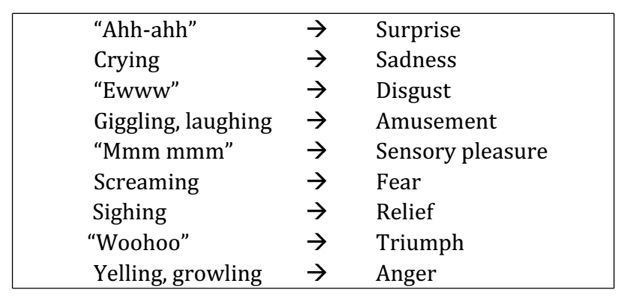

Then just last week another research group, led by Maria Gendron, revisited the topic. These researchers also journeyed to remote parts of Namibia to play prerecorded Western vocalizations (see table below) to Himba participants. This time, though, instead of picking which of two vocalizations expressed an emotion, the Himba simply listened to a recording and named the intended emotion. Cross-group recognition faltered. Himba participants reliably and distinctly identified only one Western emotion: amusement, as signaled by laughing.

Their responses did, however, match the intended Western emotions in terms of valence: whether the emotion is negative (like fear and disgust) or positive (like amusement and triumph). The Himba weren’t certain quite what to make of an “ewww,” in other words, but they did discern it meant nothing good. Perhaps, the researchers posit, “valence perception, rather than discrete-emotion perception per se, is robust across cultures, such that valence comes closer to being a core human capacity.”

We’ll need more data—a whole lot more, and collected from many different populations—to come close to settling questions about the universality of human vocalizations. (And, for that matter, how they fit in with other forms of nonverbal communication, such as facial expressions and gestures.) Likewise, the data we get won’t be easy to interpret, given the inherent difficulty of comparing groups that differ along so many dimensions. But what we now know seems to suggest that the trappings of culture cut straight into our rawest selves—deeper even than words dare to go.