Art After the Plague

How painters through the ages have responded to contagion, pestilence, and deadly epidemics

Sometime in the mid-14th century, the Dominican friars of Pisa commissioned a series of frescoes for the Gothic portico that enclosed the city’s cemetery, the Campo Santo, or Holy Field, a landmark as striking as the neighboring cathedral and its famous leaning bell tower. A simple burial ground no longer fit the tastes of a wealthy merchant community, one of the most sophisticated cities in the late-medieval world. Along with legends about early Christian hermits, the Last Judgment, and the terrors of Hell, the cemetery’s new frescoes included a harrowing Triumph of Death. It is not entirely clear who painted this extraordinary vision—Buonamico Buffalmacco or Francesco Traini, both of whom worked on the site. Neither is it known exactly when it was executed—in 1336 or sometime after January of 1348, when the bustling port became one of Europe’s first points of arrival for the virulent pandemic known as the Black Death.

Plague is still with us, and may have been with us since Neolithic times. The disease took its 14th-century nickname from the color of gangrenous flesh, a symptom that occurred when the bacterium Yersinia pestis, carried by fleas, entered the human bloodstream to cause an explosion of small clots, usually concentrated on extremities such as noses, hands, and feet. Clotting led to deadly necrosis, curable today by antibiotics. Other victims of the pestilence suffered hugely swollen, abscessed lymph glands called buboes, especially in the groin and armpits, giving Yersinia pestis its best-known name, bubonic plague. Deadlier still was the pneumonic form of plague, which developed when bacteria entered the lungs; then, victims could spread the contagion through droplets of breath or the blood they coughed forth as their lungs broke down.

Pisa lost 70 percent of its population to the Black Death. (In nearby Florence, the number of residents declined from 110,000 in 1347 to 50,000 in 1351.) The most recent restorers of the frescoes in the Campo Santo favor a date around 1336 for the Triumph of Death, relying on an article published in 1974 that compares its somber figures with contemporaneous manuscript illuminations and sermons by Dominican friars, and that finds allusions to the political situation in Pisa at the time. The evidence, all told, is slender and subjective. There really is no parallel anywhere in 1330s Europe for the scale of Death’s devastation depicted in this fresco. A series of famines had struck the region in the late 1330s and the early 1340s, but famine distinguishes between rich and poor, whereas the triumphant Death of the Campo Santo emphatically does not. Incidentally, the frescoes were nearly destroyed when an Allied bomb struck the cemetery in 1944, incinerating the wooden roof of the monumental cloister and the beaten reeds that anchored the frescoed plaster to the building’s marble walls. Their style, what is left of it, can only be seen through a glass darkly.

Triumph of Death, mid-14th century, Palermo, Artist unknown (Realy Easy Star/Alamy)

Despite the remarkable skill of the Pisa Triumph’s most recent restorers, Death remains a dim apparition. The Latin word mors and the Italian morte are feminine nouns, and thus Pisa’s Grim Reaper is barely visible as a gaunt, hollow-eyed woman with long white hair trailing behind her as she flies, clad in sackcloth, on batlike wings. She looks for all the world like the “pallid Death” of the ancient Latin poet Horace, who, like her, “knocks impartially on paupers’ huts and the towers of the rich.” Gaunt and pale Death may be, but her strength is Herculean. In Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Bad Government from nearby Siena, a fresco definitely painted before the plague in 1336–39, death prowls the countryside in dozens of different forms, with people losing their lives one by one, to a plethora of violent causes. But in Pisa, Death comes driving a combine, stalking her human crop with the very latest in 14th-century agricultural technology: an enormous, gleaming scythe. Before the invention of this ingenious labor-saver, harvesters cut grain by the fistful with sickles, but the scythe, with its curved, swordlike blade (chine) fixed to the end of a long shaft (snaith), allowed farmers to mow grain by a whole new unit of measure: the swath. The figure of Death on the walls of the Campo Santo, however, wields no ordinary scythe; the massive triangular blade of her reaping machine, more cleaver than scimitar, is forged to slice through throngs of people rather than amber waves of grain.

A heap of corpses already lies beneath her, an indiscriminate mix of kings, nuns, bishops, and ladies, along with a fur-clad merchant and a man dressed in extravagant plaid. Some of them expel their souls with their dying breath, naked babies emerging from their mouths, as angels and demons hover, waiting to snatch the newborn spirits up for Heaven or Hell. Flying above the carnage, the Grim Reaper readies her scythe with fierce concentration as she fixes her sights on the next set of victims: a gathering of aristocratic youths and maidens sheltering under a shady bower. They could be characters from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, gilded youth who escape plague-ridden Florence in 1348 by gathering in a villa outside the city walls. There, under the medieval equivalent of lockdown, they exchange stories to pass the time until the danger lifts. This pretty party in Pisa, however, will not survive so long.

Several stories in the Decameron center on the same Buonamico Buffalmacco who may have painted the Triumph of Death. He was a Florentine artist at least as famous for his pranks as for his artistry, and according to the 15th-century sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti, Buffalmacco painted some of the frescoes at the Campo Santo. The surviving contract for another project shows that he was certainly active in Pisa in 1336, but we have no record of exactly when Buffalmacco may have worked in the Campo Santo or which paintings are his rather than Francesco Traini’s. The 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari reports that the artist died in 1340, before the Black Death ever reached Italian shores, but his information on Buffalmacco, while reliably amusing, is not always accurate. And yet, even if we can only make educated guesses about the date of these paintings and the identity of their creator—and whether or not the Triumph of Death was inspired by the plague—by 1348 no viewer was likely to look at this Grim Reaper and her victims without thinking of buboes, pestilent air, and the dreadful efficiency of the Black Death.

There is nothing mysterious about what the fresco means: the terrors of this life offer only a pale foretaste of what awaits sinners on Judgment Day. The Triumph of Death in effect warns, like Lee McCollum’s 1949 gospel song “Jesus Hits Like the Atom Bomb”: “You’d better set your house in order, well, he may be coming soon / And he’ll hit like an atom bomb / When he comes, when he comes.” For those with a spiritual house to set in order, Pisa’s cathedral stood obligingly nearby, and the imagery carefully reassures its wealthy community that rich clothing and high status may afford no protection from mortality, but neither do they block a good soul from reaching Heaven.

Plague returned to Europe repeatedly after the pandemic of 1347–1353, and the anonymous painter of another Triumph of Death (see page 50), for the royal hospital of Palermo, had its ravages firmly in mind when he—and he would have been male—set to work around 1446. Rather than a female Grim Reaper, Death in this fresco (now in the National Gallery of Palermo in Palazzo Abatellis) has become a spectral cavalier taken straight from the Apocalypse:

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth. (Revelation 6:8)

The pale horse is fast becoming a skeleton, and it is the model for the anguished horse of Picasso’s Guernica, at least according to the Sicilian painter Renato Guttuso, one of the Spaniard’s friends. Death, too, is losing his skin strip by strip as he gallops through a crowd of people, some alive, some dying, some long past help. He wields an elegant bow, the favorite weapon of Apollo, the ancient god whose arrows rained down plague on the Greeks, Romans, and Etruscans. Apollo’s name means “Destroyer,” and one of his epithets was “far-darter,” yet he was also, strangely, a spirit of healing, and this figure of Death from the wall of a hospital may carry some of the ancient god’s ambiguity: to the Christian patients who suffered beneath this somber fresco, death was also the gateway to salvation. Because of Apollo’s continuing grip on the Italian imagination, 15th-century viewers would probably have associated Death’s bow with epidemic disease, and arrows feature prominently in the martyrdom of a popular plague saint, Sebastian, a young Roman soldier who was tied to a tree and shot by archers because of his Christian beliefs.

Like the Triumph of Death in Pisa, this Sicilian fresco takes special aim at a refined, sophisticated public. Many of Death’s victims dress in beautiful brocades. As the pale horse and his rider sweep across the landscape, bejeweled ladies in extravagant hats are dancing near a marble fountain to the music of harp and lute, their fingertips barely touching one another. One maiden delicately averts her eyes as a blond swain in a damask jerkin collapses to his knees in front of her, an unexpected arrow lodged in his throat. A sleek white hunting dog snaps in agitation as its sweet-faced companion (so badly faded as to be barely visible) sniffs the air, more curious than troubled. The animals sense that something is wrong, but they turn back toward the places where the eerie knight has already struck. Death is too fast for their senses.

Plague of Ashdod, 1631, by Nicolas Poussin (Masterpics/Alamy)

In 1629, plague returned with particular virulence to northern Italy, where it raged until 1631, a year that also witnessed several other disasters, such as the eruption of Vesuvius in Naples after centuries of dormancy, and the entry of Sweden, especially of Swedish cannon, into the lethal conflict between Catholics and Protestants that would eventually be called the Thirty Years’ War. In Rome, the French painter Nicolas Poussin tried to make sense of such violence and misery through his art. A brilliantly learned man as well as a marvelous painter, he chose a little-known episode from the Hebrew Bible (1 Samuel 5:6) in which the Philistines steal the Ark of the Covenant from the Temple in Jerusalem:

And it was so, that, after they had carried it about, the hand of the Lord was against the city with a very great destruction: and he smote the men of the city, both small and great, and they had tumors in their secret parts.

The Vulgate version of the text, the one Poussin knew, adds: “And rats appeared in their land, and there was death and destruction throughout the city.”

For Poussin, the Philistines exhibited the symptoms of (and the conditions for) bubonic plague, and that is why he chose this passage in the somber year of 1631. In his Plague of Ashdod (the buildings and costumes of the ravaged Philistine stronghold resembling those of ancient Rome, the terrain the artist knew best), Poussin draws a pointed contrast between the stately serenity of classical architecture and the human chaos brought on by disease—but more fundamentally by the human sin that, at least according to the Bible, caused the outbreak in the first place. Like the painter of Palermo’s Triumph of Death, he uses a host of clever visual clues to engage the other senses. Most written reports of the plague emphasize how terrible its victims smell as the organs, and then bodies, disintegrate, but Poussin, that most refined of painters, is one of the few to focus so specifically on the stench of it all, as his decorous figures avert their heads or clap their hands over their noses. With an equally acute eye, he details how human relationships break apart. In the front center of the painting, a nursing mother of two babies has just dropped dead, together with one of her children. The other infant is still alive, still trying to nurse, but unable to draw milk from his dead mother’s breast. With a hand to his face, holding his nose, holding back tears, or both, a young man, perhaps the father, bends to lift the child to safety. The limp, graying bodies that stretch beneath him may have been the heart of his beloved family just moments before, but now, on one level, they are simply corpses, a mortal danger to the baby who looks up expectantly, the spark of life in eyes that are mercifully oblivious to the horror. What does it mean to “set your house in order” under such extremity?

On the painting’s far left, the Ark of the Covenant stands on a pedestal, within the temple of the Philistine god Dagon, its gilt angels gleaming in the brilliant sun that lights up an azure Roman sky; they almost, but not quite, distract from the rats skittering up the temple steps. Dagon’s statue (as nude as an ancient Greek athlete) lies toppled beneath it. When the Philistines returned the Ark of the Covenant to the people of Israel, together with two gold models of buboes and two of rats, the plague lifted. Poussin’s painting implicitly asks the people of Rome what they intend to do to stop the wrath of the Lord in the year 1631. Still, its first owner was not exactly a repentant sinner. The diamond thief Fabrizio Valguarnera purchased Poussin’s Plague of Ashdod after a visit to the artist’s studio, hoping to launder some of his ill-gotten cash. Poussin, however, clearly created the work in a spirit of profound reflection. In his own life, he may have avoided the ravages of rats and Yersinia pestis, but he had fallen victim to another early modern plague shortly after his arrival in the Eternal City: syphilis, for which he was then undergoing mercury treatments, and which may already have flared up as the arthritis that crippled his hands in later life, and which, like Renoir after him, he defied with phenomenal courage.

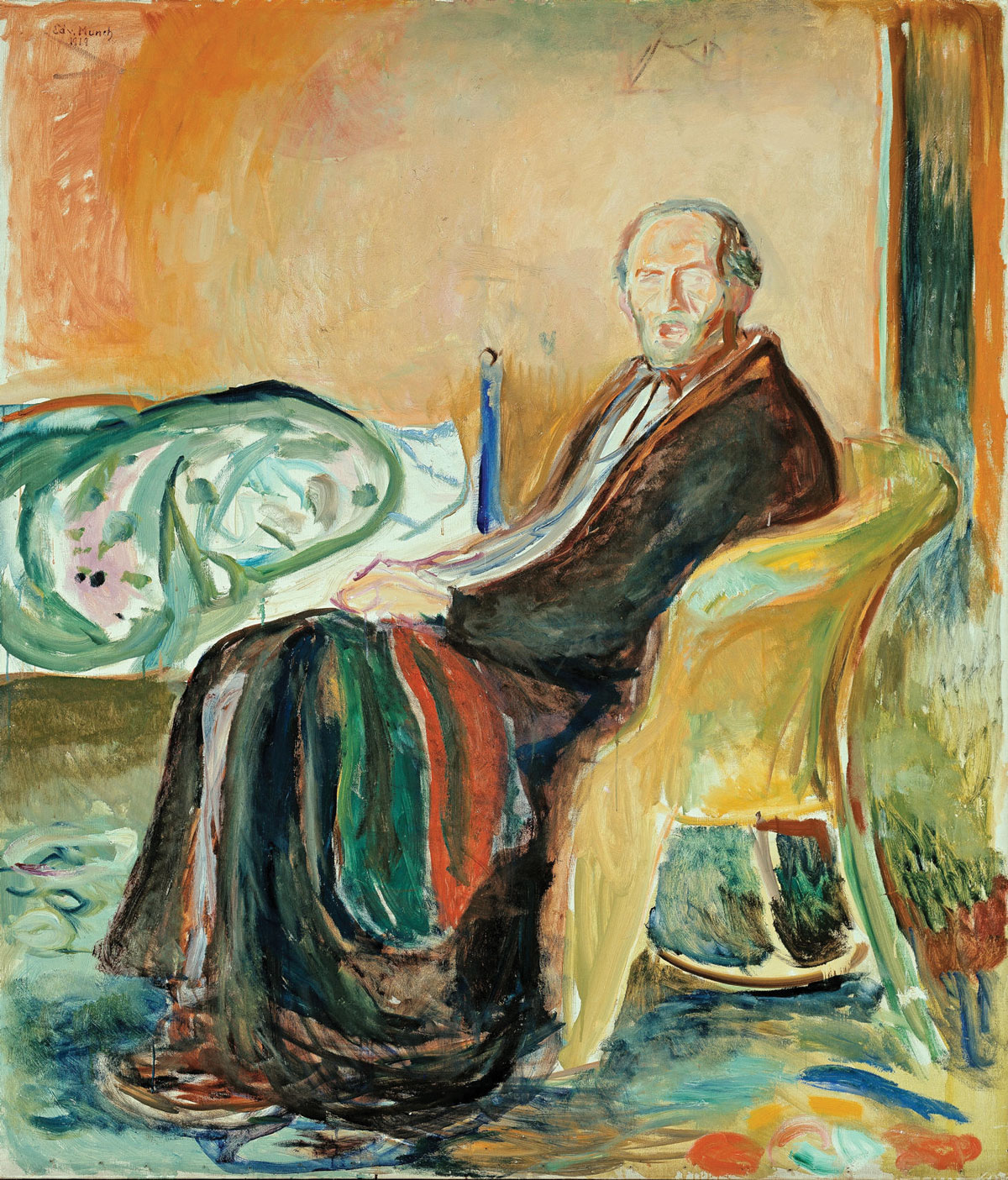

Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1918, By Edvard Munch

Syphilis manifested in its early years, the 1490s, as a “fulminating” disease, eliminating its sufferers quickly, though not as quickly as plague, that most efficient of killers. By Poussin’s time, untreated syphilis (and without modern antibiotics it remains, effectively, untreatable) had turned into the lingering torment we know today, with an initial flare, a long period of dormancy, and a final violent descent into death. Other contagions linger, too, especially the respiratory diseases, like tuberculosis, that manifest as slow, excruciating infections, or the complications of influenza and coronavirus.

The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch faced one of these long-drawn-out agonies in 1918, when he lent his vivid sense of color to a series of self-portraits with the Spanish flu. In one painting, he appears swaddled in his bathrobe, an afghan thrown across his aching knees, sitting open-mouthed and unshaven on his easy chair, his unmade bed in the background. A sea-green carpet and red-orange walls seem to bask in the endless light of a Norwegian summer, but the artist’s skull-like face suggests that even the midnight sun cannot dispel the chill terror of death. Tuberculosis claimed Munch’s mother when he was five, the great trauma of his life. His sister Sophie, who took over caring for him, died of the same disease when he was 13; his brother Peter Andreas died of pneumonia at 30. Munch himself suffered from asthma and respiratory disease throughout his life (although he died at the venerable age of 80), and no artist has ever created so piercing an evocation of that miserable feeling that flu brings of aching limbs, heaving chest, stuffed nose, and clouded brain—or in such radiant colors.

In Munch’s day, the walls of Norwegian houses were often painted in vivid shades like these reds, pinks, golds, and teal blues, but his artistry shows in the ways he adds a whole range of secondary shades to capture every nuance of light playing across a colored surface. In the contrast between his frail, hunched posture in these portraits and the bold, powerful brushstrokes that deftly create the sense of three-dimensional spaces and solid figures within them, we can take the measure of Munch’s greatness, as an artist and as a sensitive, generous soul, passionately in love with beauty and haunted by tragedy. Every breath must have been a battle, just as every stroke of the brush pained Poussin, Renoir, and another elderly arthritic, Titian. Their courage is their great gift to us.

Munch’s example shows that the slow agonies of respiratory disease can inspire great art no less than the swift drama of plague, in which life and death grapple in combat stupendous. But when Milanese cartoonist Milo Manara was put under lockdown with his wife by the novel coronavirus this past spring, he decided to celebrate combat of a different kind, in the unpretentious medium he knows best. Manara, who is now 74, made his reputation as a creator of erotic comics, filled with scantily clad or stark-naked damsels in distress who have indelibly forged the fantasy life of most Italian men of a certain age (and which most Italian women probably ignored—I know I always did). In the past few months, however, Manara has paid tribute to the women who have been performing Italy’s essential jobs under conditions that have been more perilous in his own region, Lombardy, than anywhere else in Italy, a country that faced Covid-19 early in the virus’s tour of world conquest. Some of Manara’s Covid cartoons have been collected in a book, the proceeds directed to hospitals that have faced the worst of the crisis; others have been published in Italian newspapers and The Washington Post.

One series depicts a nurse crouching on the floor, exhausted, leaning her back against the wall of a hospital corridor. Her mask has irritated her skin, her hair hangs in sweaty strands, her eyes look out dully at nothing—and suddenly she picks herself up, running off full speed to the next emergency, radiant duty vanquishing doubt and despair. A masked sanitary worker pushes her broom along a deserted city street with only a dog for company (the same dog, clearly Manara’s own, that poses with a kindly veterinarian for another touching image). But she holds her broom with such grace, and stands with such dignity in her bone-weariness, that she inspires anyone who looks at her to find, like her, that last spark of humanity—and femininity—beneath the numbing fatigue. Long-legged, cat-eyed, these women hew to Manara’s characteristic body type, but their visible signs of vulnerability make them seem absolutely real—and that is the magical thing about them. They make you think that you, like them, might be beautiful too, in spite of it all, because of it all. In an image that echoes Leonardo’s ideal man inscribed in a circle, Manara shows a female health worker dressed in her scrubs facing down a huge coronavirus, a perfect model of humanity for our perilous times.