Nearly 40 years ago, a gallery installation by the artist James Turrell so flustered exhibition attendees that it resulted in two lawsuits. In the first instance, a woman fell and injured herself after mistaking one of Turrell’s famous light sculptures for a wall. Later, another woman collapsed after becoming “disoriented and confused” by the artist’s light illusions.

“Disoriented and confused” may well describe most people’s reactions to modern and contemporary art, styles that often perplex or intimidate museum-goers. In his new book, The Art of Looking, art critic Lance Esplund doesn’t disabuse this stereotype so much as he primes readers to understand the fundamentals that shape the artwork, empowering viewers to look beyond the gallery walls and think for themselves. The Art of Looking offers close readings of modern and contemporary paintings, sculptures, and installations, while weaving biography, history, and cultural context into each critique. The following excerpt from a chapter on Turrell illustrates both Esplund’s style and his goal: “to help you learn to have faith in your own eyes and heart and gut, and to feel confident reading works of art on your own—that is, to help you begin to think like an artist.”

In 1980, a woman visiting an exhibition of the artist James Turrell at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art mistook one of his light sculptures for a gallery wall. After stepping back to lean against it and encountering nothing but illuminated, colored space, she fell and sprained her wrist. She ended up suing the Whitney. At the same show, another woman claimed she became so “disoriented and confused” by Turrell’s illusions, which magically transformed light and air into seemingly solid form, that she was “violently precipitated to the floor.” She also filed a lawsuit.

Illusionism in art is nothing new. Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia (AD 77–79), recounts that during a painting contest between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, Zeuxis’s still life was so realistic that birds pecked at his painted grapes. When Parrhasius, whose own still life was hidden behind a curtain, asked Zeuxis to unveil it, the curtain itself turned out to be a painted illusion. “I have deceived the birds,” Zeuxis said, “but Parrhasius has deceived Zeuxis.”

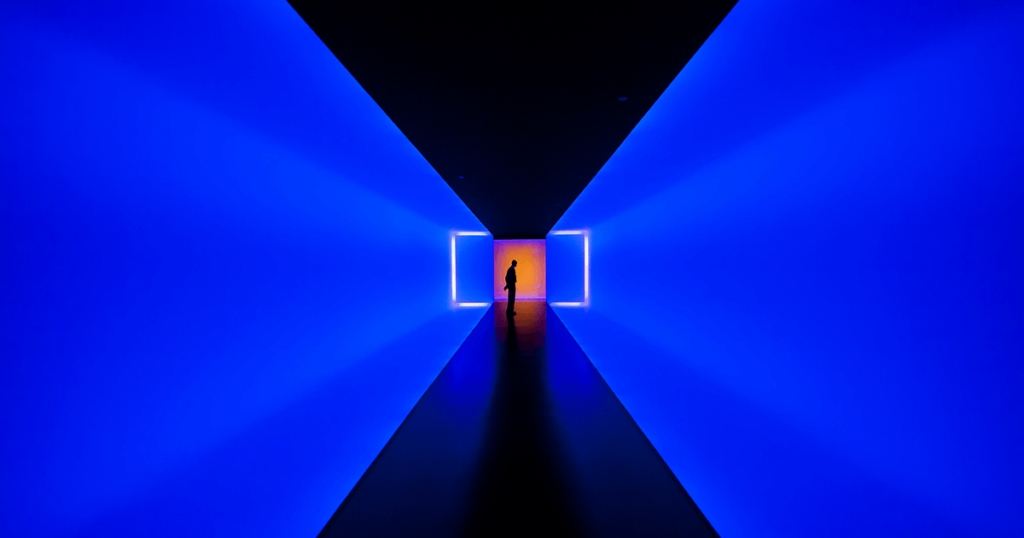

Turrell is not attempting to deceive or confuse people with his artworks—and certainly not to precipitate them violently to the floor—even though many of his light installations consist of apertures cut directly into walls and illuminated by low, indirect, artificial light in otherwise dark rooms. Turrell’s light sculptures create a number of illusions, including some that transform void into volume. And adjusting your eyes to Turrell’s sculpted light is a slow, though rewarding, process. Viewers are instructed that it can take as long as fifteen minutes for their pupils to open sufficiently to perceive the nuances in Turrell’s work. But increased visual perception does not make his artworks any less perplexing.

Born in Los Angeles in 1943 to Quaker parents, Turrell received a bachelor’s degree in perceptual psychology in 1965 and a master’s in art in 1973. He also trained as a pilot and practices pacifism. He has fused this array of interests—psychology, flight, and peace—into his art. He is best known as a proponent of the Minimalist Light and Space movement in California in the 1960s and 1970s, which brought together a group of artists, including Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, John McCracken, Bruce Nauman, and Doug Wheeler, who created atmospheric installations by controlling, to varying degrees, the interactions among architectural features, viewers, and natural and artificial light.

As your eyes adjust, in Turrell’s installations, to the artist’s vibrant fields of light, the colored, airy space before you appears to breathe, to open inward, and also to advance toward you; to harden, liquefy, and dissolve, playing havoc with your senses and your perceptions about what is form and what is not, about what is pure lighted space and what is light reflected across a wall—literally about what you are and aren’t perceiving. In these disorienting artworks, I have often timidly pushed my hand forward into their velvety light, as if reaching into another dimension, not knowing if I will encounter space or solid. “Generally, we don’t see light this way,” Turrell once said, “because we see light illuminating things. But my interest is in the thingness, the physicality, of light itself.”

Excerpted from The Art of Looking: How to Read Modern and Contemporary Art, by Lance Esplund. Copyright © 2018 by Lance Esplund. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.