Solar Dance: Van Gogh, Forgery, and the Eclipse of Certainty, By Modris Eksteins, Harvard University Press, 341 pp., $27.95

“People who buy pictures on the basis of authentication alone deserve to be cheated.” Julius Meier-Graefe delivered this expert opinion—a high-culture take on “never give a sucker an even break”—on the witness stand in 1932 Berlin. He was one of Germany’s best and most respected art critics—and, it turned out, a bit of a sucker himself, having fallen victim, along with other pillars of the art establishment, to a young German forger named Otto Wacker. A dancer and art dealer, Wacker had offered for sale 30 paintings attributed to Vincent Van Gogh, some of which Meier-Graefe had authenticated. His verdict had carried a great deal of weight, and the paintings sold rapidly until their poor quality began to raise doubts. Wacker was convicted at the trial and sent to prison, and Meier-Graefe’s reputation fell. But even as late as the 1980s, some people doubted what we now know for certain: Wacker was a fraud.

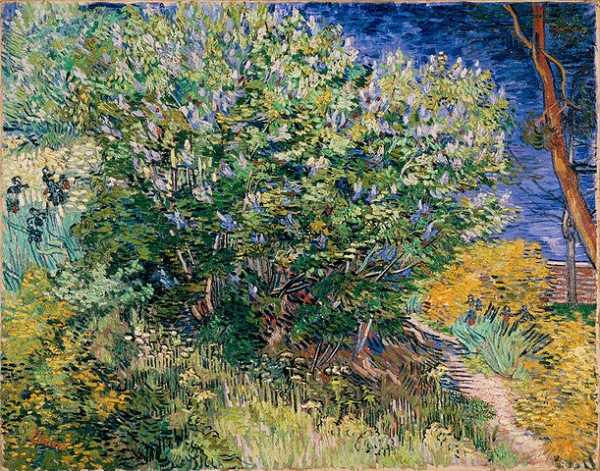

Modris Eksteins’s Solar Dance: Van Gogh, Forgery, and the Eclipse of Certainty tells the story of Wacker’s deception and discovery, and of a cultural milieu eager to be taken in. He provides, in the early section, a lively but brief retelling of the familiar story of Van Gogh’s tumultuous life and 1890 death. There follows a broad reconstruction of the artistic and cultural scene of Weimar-era Berlin—active, morally unmoored, gay, ripe for Nazi condemnation and takeover—and a loose but persistent argument that this period with its clash of values was the inflection point between the philosophical certainty of the 19th century and the doubt of the present.

Most cases of art forgery look so obvious in retrospect that it seems impossible that serious people could have been fooled. This is the nature of trickery—acceptance or chin-stroking ambivalence at the time, followed by a good loud forehead smack when you know you’ve been had. The task for any writer on fraud is to explain how the acceptance and ambivalence could ever have happened, since the reader’s hindsight will supply the skepticism necessary for the second stage.

In Eksteins’s case, the explanation falls slightly short. There was, as usual, a desire to be deceived, as manifested in the buyers’ keen appetite for Van Gogh. Famously hopeless in life, he achieved posthumous iconic status in post–World War I Germany, as one whose creative intensity and devotion to art seemed indifferent to religion and social approval. His art captured the spirit of the age and served as a Germanic bridge to the French cultural scene of the latter half of the 19th century. The Berlin art market wanted to be fooled, in other words, and Wacker obliged.

Wacker spoke with confidence and polish at his trial. (This should itself have caused suspicion; people accused of large-scale crime often get rattled.) He claimed that a man had, with British diplomatic assistance, spirited an art collection out of his native Russia while fleeing the Bolsheviks, and that the émigré (now in Switzerland) had sworn him to secrecy about his identity. Wacker’s father and brother were both painters, and the brother had been caught copying Van Gogh’s Wheat Field with Reaper, which Wacker was trying to hawk. The quality of the copies so failed to approximate the originals that when the owners of the Cassirer gallery (for years one of Berlin’s major institutions of art) unboxed the paintings—which had already taken in Meier-Graefe—they were instantly “dumbfounded by the lack of quality,” writes Eksteins, and hesitated to accuse Wacker publicly only because so many experts had staked their reputation on the canvases.

Nevertheless, buyers clamored for more Wacker Van Goghs, even after doubts emerged publicly in 1928. At his trial, Wacker reaffirmed his fictional Russian-Swiss connection. He also, Eksteins says, argued that he had done everything “by the book,” in that he had sought and received authentication certificates from recognized experts, then sold the paintings—as if their fraudulence was determined by whether the first victim fell for it. Even more remarkably, some cultural critics took his side, pointing out that Van Gogh’s Impressionism relied on the upending of reality (“Van Gogh occasionally forged himself! ”), and therefore no one could apply a standard of “reality” or “authenticity” to his paintings or their counterfeits.

The judge took a more legalistic view than the art critics. Still, Wacker spent less than two years in jail, then joined the Nazi Party and, after the war, wound up on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall, where he died in 1970. The last of his fakes in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.— part of the bequest from American banker and art collector Chester Dale—was removed from the museum’s walls in 1984. Dale is quoted here acknowledging the “controversy” (an optimistic term—by then there was little doubt) surround- ing the painting, a self-portrait. “But as long as I am alive,” he asserted, “it will be genuine.” He died in 1962.

The judge took a more legalistic view than the art critics. Still, Wacker spent less than two years in jail, then joined the Nazi Party and, after the war, wound up on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall, where he died in 1970. The last of his fakes in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.— part of the bequest from American banker and art collector Chester Dale—was removed from the museum’s walls in 1984. Dale is quoted here acknowledging the “controversy” (an optimistic term—by then there was little doubt) surround- ing the painting, a self-portrait. “But as long as I am alive,” he asserted, “it will be genuine.” He died in 1962.

Even if it doesn’t adequately explain how Wacker managed to fool anyone, Eksteins’s book does a fine job of chronicling the era’s aesthetic confusion. Less satisfying is Eksteins’s effort to fulfill the subtitle’s grand promise about the “eclipse of certainty,” which he rightly admits can be dated from any number of cultural and artistic events of that time. This great modern shift from certainty to chaos has diverse origins: politically, in the Great War; scientifically, in quantum mechanics; musically, in the debut of The Rite of Spring. Eksteins calls Wacker’s cause célèbre and the Weimar cultural moment a “prelude to the broader Western story” of disenchantment with former sources of authority and assurance. But the trenches of the Somme had already left both sides more than adequately disenchanted over a decade before.