Francis Bacon: Revelations by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan; Knopf, 896 pp., $60

The story goes that in 1963, cat burglar George Dyer fell through a skylight and crash-landed in Francis Bacon’s studio in South Kensington, London. Awakened by the disturbance, Bacon rushed into the studio and said that the intruder must have sex with him, or else he’d call the police. Thus began a seven-year relationship between Dyer, an East Ender and “nimble ‘second-story man,’” and Bacon, who was already considered Britain’s most important living painter, and who would become an international celebrity, known as much for his persona as for his paintings.

Dyer’s family and Bacon’s friend and fellow artist Lucian Freud disputed the account, yet the narrative is true to the spirit of a love affair that included Dyer’s theft of Bacon’s paintings, his arson of Bacon’s studio, and his unsuccessful attempt to frame Bacon for a petty crime. On the day that Bacon’s 1971 retrospective had its private viewing at the Grand Palais in Paris—a show that included Three Figures in a Room, a triptych of portrayals of Dyer, one of which depicts him slouched on a toilet—Dyer died of an overdose of alcohol and barbiturates in a bathroom at the Hôtel des Saints Pères. President Georges Pompidou bought the triptych for the French state.

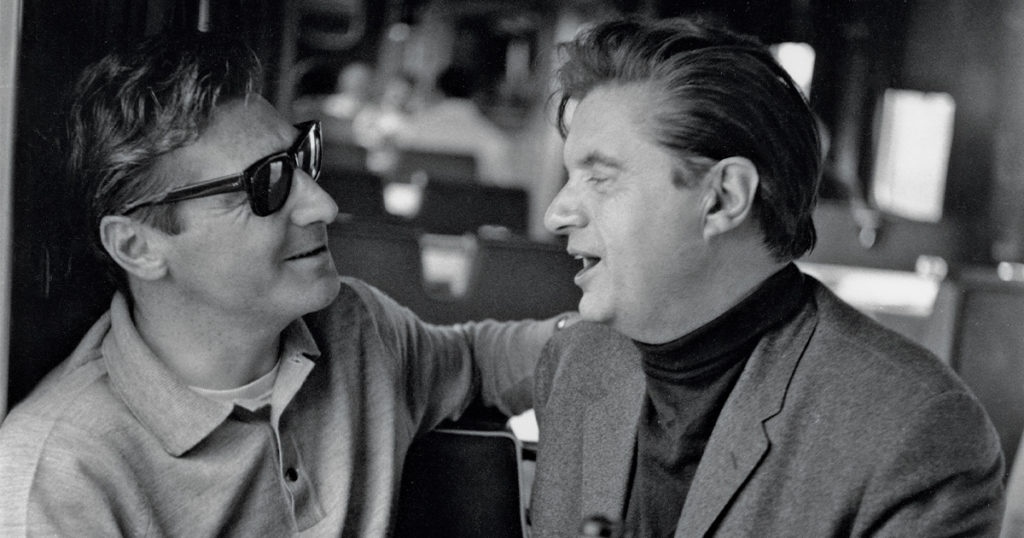

Dyer’s body was discovered in the morning, but Bacon went to his opening without revealing the news to anyone but his closest friends. A photograph taken that evening at a dinner held in Bacon’s honor at the glittering Le Train Bleu restaurant shows him standing to receive the applause of his admirers. Bacon had reached the highest echelon of success. Meanwhile, his lover’s corpse was still in the hotel bathroom; at Bacon’s request, the hotel didn’t call the authorities until the next day.

Over the years, in his grief, Bacon returned to the hotel and slept in the suite where Dyer met his end. But according to Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s new book, Francis Bacon: Revelations, Dyer was not even the love of Bacon’s life. That distinction fell to Peter Lacy, a handsome ex-pilot, alcoholic, and sadist, who once threw Bacon out a second-story window. (Coincidentally, Lacy died of acute pancreatitis in Tangier the same day that Bacon’s Tate retrospective opened in London in 1962.) “The relationship with Lacy was long, desperate, and sharply lit, with tragic overtones,” Stevens and Swan write. “The one with George was more often absurdist: loving, bumbling, melancholy.”

Although Bacon publicly ridiculed the concept of love, it appears in Stevens and Swan’s biography as one pressure among many that shaped the artist and, in turn, his work. Their book is an intellectual history of an unschooled painter, a family history that goes back several gilded generations, a cultural history of the 20th century, a financial accounting of a highborn gambler, a guide to midcentury Soho drinking clubs, a description of an evolving artistic oeuvre, and a re-created diary (Bacon did not keep one) of lowbrow fun with art luminaries, socialites, and thugs.

Bacon’s personality and his art were a mingling of contradictions. He was an atheist who depicted the Crucifixion and made the pope his subject. A 1959 essay by critic Robert Melville suggested that Bacon’s paintings were the outcome of a struggle between abstract and figurative art that expressed “the existential struggle of humanity to survive in a cruelly abstract world.” His paintings were often grotesque—meaty, distorted, screaming—but were displayed in elaborate gold frames.

His work, like his sexual relationships, was haunted and violent, exploring the interplay of the powerful and the powerless. Yet he thought of himself as an optimist who was always expecting that something marvelous was about to happen.

Describing Bacon on the floor of the Monte Carlo casino playing roulette, a beloved and enduring vice, Stevens and Swan write, “Bacon loved to win. He also loved to lose, especially everything.” Indeed, he did much to excess—eating oysters, drinking champagne, traveling abroad to sunnier climes, destroying paintings he was not pleased with—in his attempts to create a concentrated experience.

Such a life lent itself to mythmaking. Stevens and Swan document how his public persona was made, by the media and by Bacon himself. In an illuminating vignette, James Thrall Soby, a trustee at the Museum of Modern Art, mailed a list of questions for Bacon in preparation for a short book he intended to write about the artist: “What led him to become a painter? What were his main influences?” Under each question was space for a 200- or 300-word response. Bacon’s art dealers, knowing that he did not like to discuss his past, took him to a “long, wine-soaked meal” and made notes of his answers to Soby’s questions. One note read, “He made many references to his father which I think it wiser to leave out.” Some questions Bacon seemed unable to answer, and several of his responses were misleading. (Bacon said that he didn’t paint until he was 30; in reality, he started experimenting with visual art in his late teens.) Soby decided against writing the book.

There were some times in his life that Bacon never spoke about publicly—visits to Germany and France for a cultural education in the 1920s, and a couple of years during World War II when he lived in a rural cottage near Petersfield, where the asthmatic painter escaped the clouds of dust kicked up by Nazi air raids on London. Bacon, who portrayed himself as unschooled and socially exuberant, may not have wanted to highlight his having attended drawing classes in Paris or the years he lived in seclusion with his childhood nanny far from the dangers of the Blitz. Stevens and Swan evoke these periods using other sources, including interviews with people who had known Bacon or his confidants.

One of the pleasures of comprehensive biographies like this one is seeing familiar set pieces nestled in rich context. At a 1949 ball in London thrown by Lady Rothermere, Princess Margaret performed a few Cole Porter songs. “She could not deliver quite the right slink despite some wriggling,” write Stevens and Swan. While the rest of the guests applauded, Bacon booed her. “The band sawed to a stop. The princess reddened and rushed from the room, with several flustered ladies-in-waiting following.” Bacon later said of the incident, “I don’t think people should perform if they can’t do it properly.”

Stevens and Swan write that “proper form was no longer obvious midway through the century, not after the butcher’s bill from two wars, and [Bacon] took a demonic delight in the upended performance and the torn-away mask.” He yearned for an exhilarating and difficult freedom.

A witticism often attributed to Bacon is, “champagne for my real friends and real pain for my sham friends.” In this biography, the quotation is situated in a confrontation between Bacon and painter John Minton. Bacon buys a bottle of champagne, pours it over Minton’s head, and massages it into his hair. “Champagne for my sham friends and real pain for my real friends,” he says.

A subtle but apt transference of words: For Bacon, pain was meaningful, and thus a gift.