At Play in the Fields of the Bored

America’s newest city parks are chock-full of things to do—but what happened to the delights of idle time in a natural setting?

It’s a typical weekday morning at Klyde Warren Park, a five-acre rectangle on the edge of Dallas’s arts district. Two teenage girls play Jenga on the grass while a middle-aged woman reads a copy of Bon Appétit. Elementary-school children on a field trip let off steam in a playground as people begin queuing up at the food trucks—by noon, the lines will extend from the sidewalk through beds of maiden grass and Texas sage. Near the milkweed garden that attracts migrating monarch butterflies, construction workers nab a table. On the more crowded of the park’s two lawns, people take selfies, with Dallas’s downtown towers rising behind them; on the quieter green, a woman lies on her back, enjoying her solitude and the still-cool sun. The scene is so picturesque, so quietly alive, that nobody seems to pay attention to one incongruous feature: the eight-lane freeway with gridlocked traffic that dips below the park on its eastern edge, emerging on the other side and receding westward.

Klyde Warren Park, constructed over a recessed stretch of the Woodall Rodgers Freeway, is a source of civic pride, a weekend magnet for residents from throughout the region, and a marketing hook used to lure residents to the glass condominium towers nearby. But in a broader sense, it is emblematic of the kind of public space favored by American cities at the moment—meticulously designed and programmed, city owned but privately funded and maintained, with an ever-changing array of carefully curated experiences. At Klyde Warren, you can play pétanque or croquet, laser tag or chess. You can practice your putting or take a ballroom dance class. No need to bring your own Jenga blocks; they can be checked out from the well-stocked Reading and Games Room. Public spaces such as this—picturesque destinations with plenty to offer and little left to chance—are made for the Instagram age. If they enrich public life in an era when the competition for resources is intense, they’re also oddly suited to an American culture in which the unknown is increasingly feared, and being aimless is the biggest sin of all.

If Frederick Law Olmsted hoped to “shut out the city from our landscapes,” urban parks now invite the bustle of city life into their verdant settings. (Bryant Park, New York City/iStock)

Klyde Warren Park was born out of scorned civic pride. In 2001 Boeing, looking to move its corporate headquarters from suburban Seattle, narrowed the choice to Dallas or Chicago—then opted for the latter in part because, as a company spokesman said at the time, “a vibrant downtown atmosphere was important.” The rejection prodded politicians and civic leaders into putting a two-block deck topped by a lavish park over the partly submerged freeway between the somnolent arts district and the residential Uptown area. Half of the $114 million budget was provided by donors, including one who wrote a $10 million check in return for having the park named after his then nine-year-old son; city and state government provided the rest.

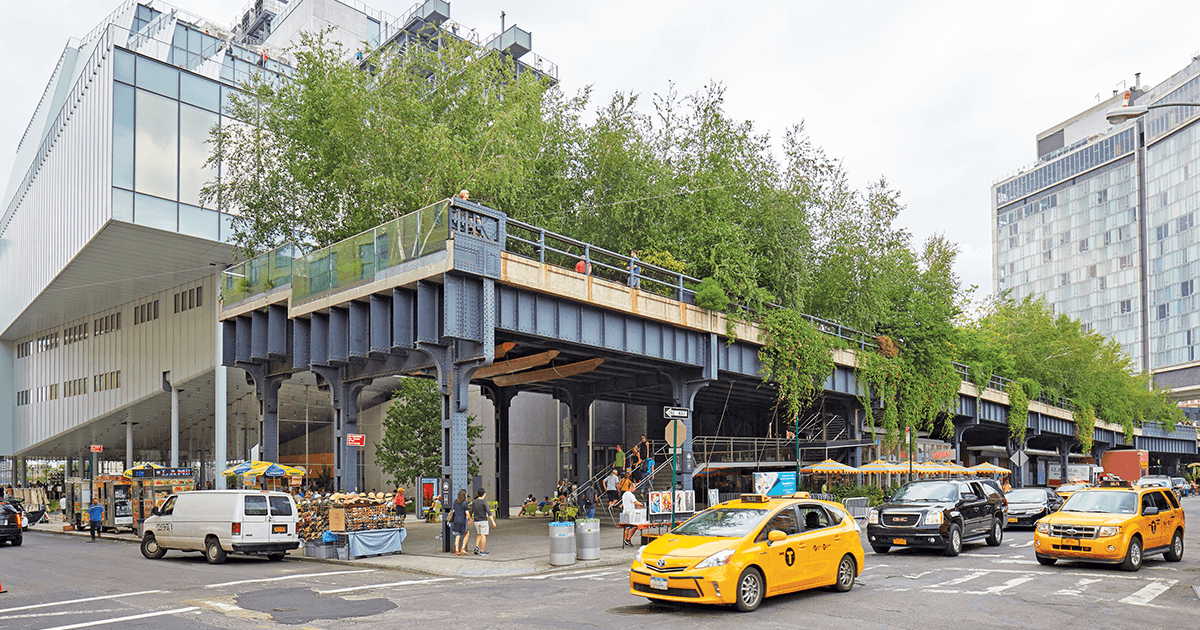

The finished product debuted in 2012, eight years after Chicago’s Millennium Park and three years after the first phase of the High Line opened in New York City. In each of those spaces, a drab site—rail yards in Chicago, a long-abandoned elevated freight track in New York—was turned into something seductive, at once memorable and one of a kind. Millennium Park and its 24.5 acres along Michigan Avenue draw millions of visitors annually with such attractions as the massive bean-shaped, mirrorlike Cloud Gate by British sculptor Anish Kapoor. The High Line strings 1.5 miles of landscaped walkway 30 feet in the air, with stylized towers lining the promenade.

These are the best-known examples of urban America’s new public realm, but they’re by no means alone. In Cleveland, the venerable and centrally located Public Square now features gentle hillocks and a butterfly-shaped walkway. Abandoned industrial wharves in New Orleans, downriver from the French Quarter but hidden behind a floodwall, have been recast as Crescent Park, which can be accessed by an arching steel bridge. San Francisco’s new three-level transit center is topped by a

5.4-acre park complete with a redwood grove and willow-shaded pathways.

Looks aren’t the only selling points. Campus Martius Park in downtown Detroit imports 200 tons of sand each summer to conjure up a beach, with refreshments served from a café housed in recycled shipping containers. Franklin Square in central Philadelphia, one of five large park spaces marked out for the city by William Penn in 1682, reopened in 2006 with a carousel and an 18-hole miniature golf course dotted with playful takes on local landmarks. In addition to such ongoing attractions as the dog park and putting green, Klyde Warren Park hosts open-mic poetry readings and family science activities, as well as hour-long sessions in yoga, tai chi, and Zumba dancing. Mass water-gun fights were a Friday afternoon fixture last summer.

Compare the emphasis on events and activation with the vision of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. When the pair designed New York’s Central Park, Olmsted sought to “completely shut out the city from our landscapes,” crafting refuges where people “may stroll for an hour, seeing, hearing, and feeling nothing of the bustle and jar of the streets, where they shall, in effect, find the city put far away from them.”

Granted, this wasn’t so hard when working with Central Park’s 843 acres, or with the 1,017 acres of coastal sand dunes cloaked with shrubbery and trees that became San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in the late 1800s. But that Edenic vision of solitude and separation, unquestioned well into the 20th century, inspired even such relatively small spaces as Bryant Park in New York City, with 240 London plane trees framing a lawn and fountain—an orderly retreat set behind a wrought-iron fence. The spell was so powerful that Bryant Park was named a city landmark in 1974; by then, the space was also such a notorious spot for drug dealing and prostitution that a subsequent grant by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund to renovate the adjacent New York Public Library included a stipulation that Bryant Park also be improved.

Fast-forward to 1992, when Bryant Park reopened following a makeover led by the landscape architect Laurie Olin. Olin’s firm kept the seminatural sense of order while opening things up—adding an extra entrance, for example—and by such nimble moves as replacing the ivy under many trees with decomposed granite, to create space for people to gather, and budgeting for eye-catching displays of colorful flowers along paths.

“Parks were eroded and perceived as dangerous, and they were dangerous,” Olin says. “They’d been designed as sanctuaries to get out of the city, so when criminals settled in, other people stayed away.”

Bryant Park’s new look extended beyond physical design: the space also became home to an ever-shifting constellation of attractions that might bring in people throughout the day. In the mood for Ping-Pong? Come on by. Outdoor movies? They’re a Monday night staple all summer long. A cart filled with free art supplies? Open daily during the spring and summer until eight P.M. Juggling lessons, or an elegant lunch, or a carousel ride? This is the place!

Although the 9.6-acre site still belongs to New York City’s public park system, most of the financing for the $21.5 million annual budget comes from concessions, private resources, and corporate sponsors—Bank of America, for instance, puts in $2.5 million to underwrite an annual Winter Village, with ice skating and European-style open-air market stalls. The park is also managed privately, with a four-person horticultural crew among the staff of 108 full- and part-time employees.

Overseeing the production is Dan Biederman, who has been involved since the renovations began and whose firm has worked in more than two dozen cities, including Dallas. Biederman served as a consultant during the design of Klyde Warren Park. When I visited Dallas in 2009, I couldn’t imagine a lively urban park existing there. Biederman never had doubts, taking note of the apartments and condominiums lining Uptown’s streets.

“Millennials are walkers and urbanists, and they’re looking for a place to go. They’ll create one if you give them the opportunity,” Biederman says. The park’s private backers, he says, “understood what a programmed park could be. They didn’t want a big space that looked abandoned. That was part of it, too.”

Not surprisingly, there are landscape architects who bridle at the notion that their job, in effect, is to design attractive voids that can then be filled by the commotion of crowds assembling for specific, carefully planned events. “Whatever happened to breath, lungs, the Olmsted thing?” asks Mary Margaret Jones, president and senior principal at Hargreaves Associates. The firm designed Crescent Park in New Orleans and has worked in cities as varied as Louisville, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia.

“I remember a client—we showed him hills on a proposed design, and he said, ‘What do they do?’ We said … ‘They’re hills,’ ” Jones recalls. “Not everything in a park has to do something. People need space for their brain as well, their imagination, and their souls. We’re inexorably drawn to wanting to be unprogrammed and outdoors.”

A variation of this argument is popular with sociologists, urban designers, and cultural geographers who champion so-called Loose Space, a phrase that was the title of a 2007 collection of essays edited by Karen Franck and Quentin Stevens. In their introduction, Franck and Stevens stressed the importance of spaces within the public realm that “allow for the chance encounter, the spontaneous event, the enjoyment of diversity and the discovery of the unexpected.”

Put that way, who could disagree? But not all spontaneous events are created equal. When the “chance encounter” involves a man hassling a lone woman, or a strung-out drug addict approaching your children, the enjoyment sours fast.

“Part of the looseness of the public realm is not being able to control social distance or choose how and when we will interact,” Franck and Stevens wrote. A few pages later, though, they shrugged off that concern: “Encounters with what is shocking or troublesome can be a benefit, resulting in greater acceptance, tolerance and personal growth.”

Similarly, the idea that public parks or plazas might be privately managed strikes some observers as a contradiction in terms. It’s “pacification by cappuccino,” in the memorable phrase of sociologist Sharon Zukin, who teaches at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York. “The disadvantage of creating public space this way is that it owes so much to private-sector elites,” Zukin argued in her 1995 essay “Whose Culture? Whose City?” “The cultural strategies that have been chosen to revitalize Bryant Park carry with them the implication of controlling diversity while re-creating a consumable vision of civility.”

If such arguments resonate in academia, they get little traction with city hall decision-makers who welcome the energy that accompanies a popular new park—as well as a boost to the local economy. When Klyde Warren Park and its designer, OJB Landscape Architecture, won a 2017 Award of Excellence from the American Society of Landscape Architects, OJB’s project narrative went beyond aesthetics and the environmental benefits to emphasize the $1.3 billion economic spillover effect and the substantial new tax revenues.

“I probably give 10, 15 tours a year to groups from wherever that are looking to do a deck park, or a rooftop park, and want to know more about how we made it happen,” says Michael Gaffney, senior vice president of operations at Klyde Warren Park. He also describes how the space continues to be tweaked as more is learned about what people want. One item on the to-do list is to expand the busy playground by removing the native plant garden alongside it.

“It was intended as a quiet reflective area—but the reality is, there’s no reflection going on here,” Gaffney says. “I call it the park of mayhem. People are here to have a good time.”

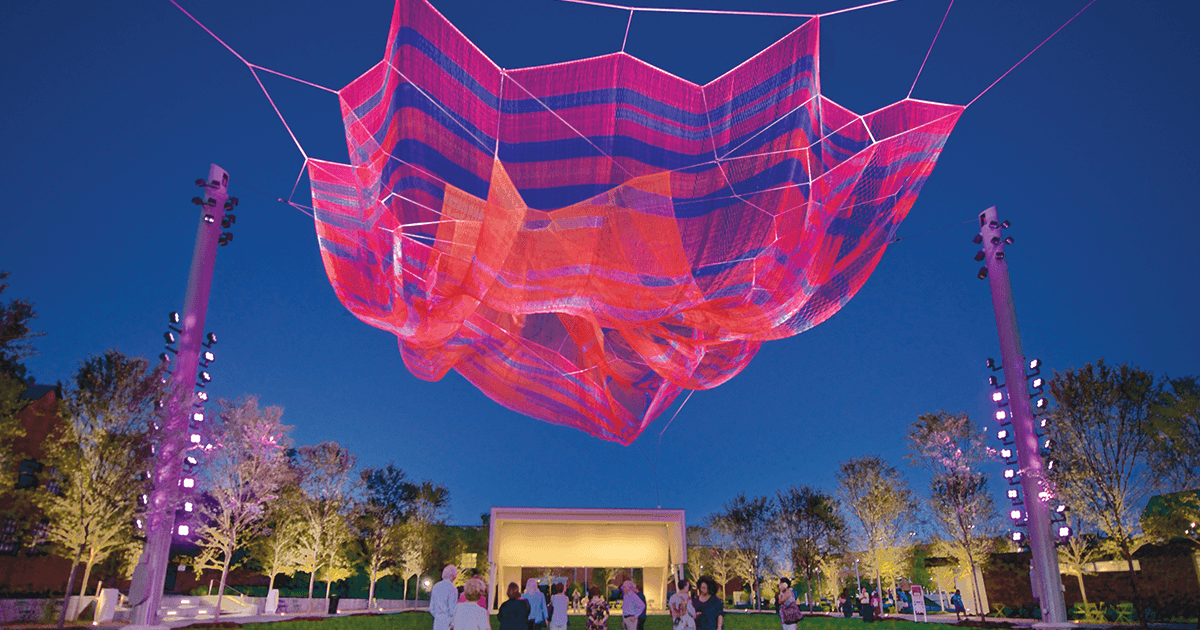

Janet Echelman’s 2016 installation Where We Met,at Greensboro’s LeBauer Park; there, says a parks official, “programming [is] everything.” (Lynn Donovan)

In LeBauer Park in Greensboro, North Carolina, there’s no freeway beneath you, and the food trucks are a weekly rather than daily presence, but the 4.5-acre space that opened in August 2016 aims to please, with a putting green, a Ping-Pong table, and an outdoor reading room. Children can splash in a shallow fountain or explore the brightly colored sculpted playground in the center of the park—the most prominent visual feature in what is otherwise fairly flat terrain. The schedule includes yoga classes and lunchtime concerts, a jazz picnic on Sunday afternoons, and a weekly event for dogs and their owners billed as Yappy Hour. The similarities to Klyde Warren Park are by design: LeBauer Park’s landscape architect was also OJB Landscape Architecture, and Biederman’s firm served as the programming consultant. At the opening ceremonies, Mayor Nancy Vaughan predicted, “There are going to be cities all over this country who are going to say, ‘I wish we had a LeBauer Park like Greensboro has.’ ”

LeBauer Park happens to be located across the street from another young civic space in this city of 290,000. Center City Park opened in December 2006 amid parking garages and office buildings. A brick path shaded by birch trees curves along one side of the 1.9-acre space, with wooden benches beneath thick pines on the other. Bands of native plantings and grasses hug walkways along Elm Street. The centerpiece is a grand fountain that is irresistible despite signs imploring the public to stay out of the water and off the granite walls and ledges.

Not only do the two spaces look different, they also function in different ways. “Center City Park was very much designed as an escape from the daily grind, with a more traditional aesthetic,” says Rob Overman. He’s the executive director of Greensboro Downtown Parks Inc., which manages both spaces. “Programming was an afterthought. At LeBauer, programming was everything.”

Overman grew up in Greensboro and worked at Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks, among other jobs, before taking the post in 2017. Though his own preference is for Center City Park’s textured sense of a natural retreat, Overman readily admits that “LeBauer Park has become a destination” where families might spend an entire day enjoying activities both at the park and at the adjacent city-run Greensboro Cultural Center.

He says that running public spaces on a private model also means accepting the presence of homeless men and women who spend hours at a time in Greensboro’s downtown parks, day after day after day, some down on their luck, others suffering from mental illness or substance abuse. They might panhandle. They definitely put other people on edge. Even per capita, the number of these people is nothing like what you see in New York or San Francisco. But they stand out in a downtown still trying to establish itself as a place where people from other neighborhoods and nearby suburbs will want to visit more than once. That’s likely part of the reason why LeBauer Park’s crowded playground and interactive fountain are placed front and center. On the day I visited, the men and women I assumed to be homeless were hanging out along the far side of the park, against the rear of the Greensboro Historical Museum. Consigned to the shadows, as it were.

“We program for every demographic in these parks,” Overman says. “Maybe we need to start doing that for homeless folks. They’re not going anywhere, so we should at least try and help out a few of them and let them know they’re included.”

In an era when park spending is a low government priority, private donations and corporate sponsorships are essential. LeBauer Park exists because of a $10 million bequest in the will of Carolyn Weill LeBauer, who died in 2012. Center City Park was a private creation as well. They’re both now within the city park system, but Greensboro provides only $350,000 of the $850,000 annual budget for maintenance, programming, and security. Overman and his full-time staff of four must raise the rest—thus the discreet signs in LeBauer Park informing you that the jazz picnics are sponsored by a real estate firm. A law firm underwrites the free Wi-Fi. The maintenance cost for the playground is picked up by a financial-planning firm. The entire park can be rented for corporate gatherings or private events, though Overman keeps the main walkway open to people passing through.

Closing part of a public park for private events is not uncommon these days. In April 2016, a chainlink fence cloaked in a black tarp enclosed Philadelphia’s Franklin Square for six weeks. The public was allowed inside during the day, but everyone had to leave by six P.M. so that the park could host the Philadelphia Chinese Lantern Festival, with its billowing dragons and fantastical illuminated creatures—and $17 admission fee. The park’s manager, Historic Philadelphia Inc., raised upward of $200,000 from ticket proceeds, but detractors said the tradeoff was too much: “The decision to monetize Franklin Square in the evenings takes the philosophy of privatism to a disturbing new level,” wrote Inga Saffron, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s architecture critic. Despite such complaints, the festival has become an annual event. The wrapping that faces the city has been redone in muted Asian patterns, and some sections of the chainlink fence swing open during the day so that passersby can glimpse the interior. Even so, a visit during the festival’s off-hours feels like an intrusion, as if your presence amid the dormant festival props is merely being tolerated until sundown.

When I visited Dallas last year, a black Nissan Titan pickup was parked near the main entrance. A sign next to the truck bore the Nissan logo and the words, “Proud Sponsor of Klyde Warren Park.” So much for Olmsted’s goal of shutting out the city.

New York’s High Line starts at the Whitney Museum; the park, rising 30 feet in the air, is representative of “urban America’s new public realm.” (iStock)

Cynics might dismiss the current wave of pumped-up parks as the latest in a series of mostly unsuccessful attempts to refresh faded American cities—the 21st-century successor to the downtown pedestrian malls of the 1960s, a response to the popularity of suburban shopping centers. Or the festival markets (think San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square or the Navy Pier in Chicago) that stuffed obsolete masonry buildings with fudge shops and craft stalls. Or those “futuristic” atrium hotels (such as the Hyatt Regency Atlanta) that used Jetsons-like design flourishes—illuminated glass elevators!—to distract from how resolutely they turned their backs to the still-feared downtown streets.

The difference this time is that, in a broad sense, urbanism is in vogue. No longer must you visit buoyant coastal cities to find artisanal coffee, locally brewed IPA, and modernist furniture stores. Bike lanes are ubiquitous, along with fully landscaped and protected bicycle paths. Millennials are drawn to the downtown scene, as are corporations wanting to hire smart young workers. Facebook leased all the office space in San Francisco’s two newest towers. McDonald’s operations last year relocated to Chicago’s West Loop from suburban Oak Brook. General Electric’s headquarters office is migrating from Connecticut to Boston, a process that began in 2016 and will include a new 12-story building near the waterfront. Boeing, it turns out, was ahead of its time.

Curated public spaces, with their targeted novelties, build on all this. They’re driven less by city planners or nature lovers than by advocates who dream of a high-profile park as a gathering place for locals, as a regional anchor. What happens, however, when the novelty wears off? It’s hard to imagine a scenario in which Millennium Park or the High Line loses its allure. But many of the festival marketplaces soon fell flat, and nearly all of the pedestrian malls reopened to automobile traffic within a decade or so. You can conceive a scenario not too far in the future in which food trucks become passé, and the Saturday morning yoga courses in the downtown park are something your aunt did.

“Uses change over time, along with people’s desires for what they want to do,” Mary Margaret Jones points out. “Ultimately, you have to design a memorable space.”

That’s the charge for landscape architects. The charge for the rest of us might be to welcome a programmed public landscape—but not lose sight of the transformative spell nature can cast within an urban setting. It’s easy to forget this in an age of special interests and focused desires, where city dwellers call for skate parks, dog parks, meditation gardens, you name it. And such spaces serve a function. They strike chords of pleasure with their constituents and bring different groups of people together. Yet there’s something reductive in the notion that large parks should be measured by how well they function as containers for certain well-defined needs—a narrow vision of public space that assumes we all want to be served or dazzled in predictable ways. No matter how much fun they might offer on a first or second visit, our new curated spaces can start to feel like a GPS device. You’re directed to follow an efficient route from Point A to Point B, with none of the detours or side roads that might beckon on an old-fashioned map.

That’s fine when you’re trying to get from A to B. But what if one’s desire is to go astray? The physical experience of a park is enhanced when some things are left to chance. When your senses are heightened by the ephemeral sensation of smells and sounds and shifting layers of greens, and you slow down simply to take things in. When a space encourages solitary reflection rather than urging you—as do certain signs at a waterfront esplanade in Washington, D.C.—to “Celebrate. Post. Tag.” Laurie Olin told me that “the hardest thing to produce today in our society is calm. So many people are so connected, so plugged-in, so in need of stimulation.” Public parks should still allow room for the unexpected. The serendipity of the moment. Small patches of earth where things are a little loose, where you can unplug and disconnect and let your mind wander, and where it’s okay if you don’t get any likes.