In 1801, when I was in my sixteenth year, my father, my eldest half brother, and myself, attended a wedding about five miles from home, where there was a great deal of drinking and dancing, which was very common at marriages [in] those days. … After a late hour in the night, we mounted our horses and started for home. I was riding my race-horse.

A few minutes after we had put up the horses, and were sitting by the fire, I began to reflect on the manner in which I had spent the day and evening [and] felt guilty and condemned. … [A]ll of a sudden, my blood rushed to my head, my heart palpitated, in a few minutes I turned blind; an awful impression rested on my mind that death had come and I was unprepared to die. I fell on my knees and began to ask God to have mercy on me.

—Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, The Backwoods Preacher, 1856

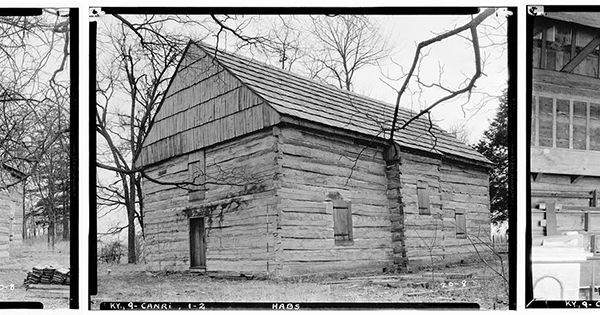

Thus did Peter Cartwright, one of the most fiery evangelical Methodist preachers of America’s first century, describe the beginning of his conversion experience at the 1801 Cane Ridge Communion, a famous revival meeting in southwestern Kentucky that eventually drew, according to some sources, tens of thousands of previously unchurched, or at least religiously lukewarm, souls. By other accounts, there may have been only thousands, but even allowing for the exaggeration of pious observers, the Cane Ridge gathering was one of the most significant religious events in American history. “Lord, make it like Cane Ridge,” was a frequent prayer at American revival meetings for decades afterward.

The spiritual awakening of the young, largely unschooled (but not illiterate) Cartwright was, in many respects, typical of the evangelical conversions that would characterize American life throughout many cycles of religious fervor, exemplified in revival meetings in both the 19th and 20th centuries. The earliest “born-again” conversions, legally protected (like all religious choice) by the new Constitution, laid a social template for the widely held American concept of religion as an individual rather than a strictly institutional relationship with God. This template, which fostered acceptance of many other (though not all) types of conversions, has lasted into our own time, when an increasing number of Americans call themselves “spiritual, but not religious”—an amorphous self-description that surely would have horrified biblical literalists like Cartwright.

Born in 1785 in Amherst County, Virginia, Cartwright grew up in a pioneer farm family that pulled up stakes several years after the end of the Revolutionary War (Peter’s father was a veteran) and headed west. Kentucky was the lawless frontier, and Logan County, where the family settled down, was known as Rogues’ Harbor. As Cartwright colorfully recounts in his best-selling memoir:

Here many refugees, from almost all parts of the Union, fled to escape justice or punishment; for although there was law, yet it could not be executed, and it was a desperate state of society. Murderers, horse thieves, highway robbers, and counterfeiters fled here until they combined and actually formed a majority. The honest and civil part of the citizens would prosecute these wretched banditti, but they would swear each other clear; and they really put all law at defiance, and carried on in such desperate violence and outrage that the honest part of the citizens seemed to be driven to the necessity of uniting and combining together, and taking the law into their own hands, under the name of Regulators. This was a very desperate state of things.

Gun battles and lynchings (the latter usually carried out by Regulators against criminals) were the stuff of daily life, and it was not easy to determine who was on the side of the law. Puritan hegemony, which had restrained ordinary criminal behavior as well as religious dissent in the early days of colonization in New England, did not exist on the frontier. Thus, the arrival of circuit-riding preachers, whose theological credentials came not from any eastern divinity school but from their own conversion experiences, was greeted as a force for much-needed order. To churchgoing Americans in long-established small towns in New England or even in the large, less orderly cities of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, revival meetings on the frontier looked like wild, disorderly melees bordering on the savage. To settlers on the frontier, the revivals brought hope of a new kind of security based on some sort of religious affiliation, which might also encourage the establishment of functional law enforcement institutions. As Richard Hofstadter observes in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), “The style of a church or sect is to a great extent a function of social class, and the forms of worship and religious doctrine congenial to one social group may be uncongenial to another.” The “possessing classes,” Hofstadter argues, have generally shown more interest in reconciling religion with reason and with the observance of traditional liturgical forms. The “disinherited classes,” by contrast, have been moved more by emotional forms of religion and are hostile to ecclesiastical hierarchy associated with the upper classes.

The one unusual aspect of Cartwright’s upbringing on the frontier was that his father sent him, for a brief time, to a boarding school run by a traveling preacher for the Methodist Episcopal Church. There Cartwright learned to read and write—allowing him to greatly enhance his future prospects in spite of his expressed disdain for higher education (at least insofar as it was considered a qualification for the ministries of upper-class denominations). Had he been illiterate, Cartwright would not have become one of the best-known Methodist ministers of his day. By the 1820s, frontier communities were beginning to regard the presence of a school, which often doubled as a church, as a necessary sign of civilization. A Kentucky farmer might not have had any use for a circuit-riding preacher with a degree from the Yale Divinity School, but he would have valued a minister who could actually read the Good Book.

An estimated 90 percent of the residents of the brand-new United States of America were unchurched when Cartwright was born, during the early years of the Second Great Awakening. Unchurched did not mean that Americans were indifferent to religion but that they were in the process of moving to areas of the country beyond the reach of existing, formal religious institutions. Thus, a large proportion of the population was ripe for proselytizing preachers who spread out across the land over thousands of miles. Religious conversion, at least among Protestant denominations, became a feature of daily life in the formative decades of the Republic. Furthermore—then as now—born-again experiences that took place without exchanging one denomination for another were also considered forms of conversion. And—then as now—families whose faith was expressed mainly by saying grace before meals and going to church on Sunday could be irked and unsettled by a member who suddenly placed Jesus at the center of every aspect of life. Cartwright does not tell us how his father and brother reacted to his sudden discovery that dancing and riding racehorses—which they enjoyed—were not only a waste of time but also sinful.

Cartwright’s description of his own conversion moment at Cane Ridge is typical of many accounts by literate converts:

To this meeting I repaired, a guilty, wretched sinner. On the Saturday evening of said meeting, I went, with weeping multitudes, and bowed before the stand, and earnestly prayed for mercy. In the midst of a solemn struggle of soul, an impression was made on my mind, as though a voice said to me, “Thy sins are all forgiven thee.” Divine light flashed all round me, and it really seemed as if I was in heaven; the trees, the leaves on them, and everything seemed, and I really thought were, praising God. My mother raised the shout, my Christian friends crowded around me and joined me in praising God; and though I have been since then, in many instances, unfaithful, yet I have never, for one moment, doubted that the Lord did, then and there, forgive my sins and give me religion.

Many conversion accounts have an adolescent tone (whether or not they actually took place in adolescence). Nearly all such stories display an exaggerated consciousness of both sin and the possibility of redemption, a sense of being directly addressed by an otherworldly power, and supernatural manifestations within the natural world. Cartwright, like Saul on the road to Damascus, experienced a period of blindness. Flashing lights are as much a staple of conversion accounts from 19th-century revival meetings as a white light at the end of a tunnel in every modern movie about near-death experiences. Unlike Augustine’s Confessions, American adolescent conversion stories generally skirted the subject of sexual sin: an excessive fondness for dancing was as close as Cartwright got to the heart of the matter. These religious awakenings, however sudden and undirected by ecclesiastical hierarchy, nevertheless produced profound changes in many personal lives—my definition of a genuine conversion. It took time for existing religious institutions to catch up with the westward movement of settlers, and “backwoods” preachers, many self-appointed, would fill the gap.

Cartwright eventually settled in Illinois, where he mixed religion and politics with zest. Like most evangelicals, he was quick to denounce any hint of government interference with religion but was uninterested in the other side of the founding constitutional bargain, which restrains religious interference with government. In his first run for public office in 1832, the Reverend Cartwright, a Democrat, defeated a Whig, a young store clerk named Abraham Lincoln, for a seat in the Illinois state legislature. In 1846, however, Cartwright ran for Congress and was defeated by his former opponent, now a lawyer. Lincoln, who had trained for his profession with an older attorney instead of attending law school, shared Cartwright’s lack of formal schooling but not his biblically literal religious convictions. During the 1846 campaign, Cartwright charged Lincoln with deism and “infidelity”—an accusation based partly on the well-known fact that Lincoln did not belong to any church (an omission less acceptable socially in the 1840s than it had been when Cartwright was young ). And though Cartwright dismissed Enlightenment thought, Lincoln was drawn to thinkers who ranged from the most liberal Protestants to outright atheists. Two of the books Lincoln was reading at the time of his first campaign against Cartwright were Enlightenment classics—Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason and Constantin Volney’s The Ruins.

Cartwright’s encounters with Lincoln (not altogether unfriendly, because they would come to agree about slavery) embodied a confrontation between two competing forces that have shaped American religious culture to this day. The first, exemplified by Cartwright’s conversion, was a propensity for highly emotional, nonhierarchical, personal forms of religion associated with biblical literalism and revivalism. The second was a struggle within mainline American Protestantism to reconcile Christian faith with Enlightenment rationalism. Lincoln the freethinker—a man who, whatever his private beliefs were, would have nothing to do with organized religion—was shaped in part by the individualism of the frontier and in part by the mainstream religious split that encouraged not only the establishment of more liberal Protestant denominations but also the rise of secular American freethought.

[adblock-left-01]

Between 1790 and 1830, roughly half of the Puritan-descended Congregationalist churches in Massachusetts had been transformed into Unitarian congregations. The spread of less doctrinaire forms of Protestantism was closely related to the emergence in the early Republic of leaders who eschewed traditional religious institutions. This split between the conventional Puritan-descended denominations and more liberal intellectual denominations was carried westward by settlers—first from New England to Upstate New York, then to the Midwest, and finally to the Pacific Northwest.

The Unitarians, while not aggressive proselytizers in the fashion of evangelical revivalists, converted plenty of Puritans to a personal form of religion that stressed reason and good works rather than blind faith, predestination, and divine fury. John Adams, for instance, belonged to this group—though he would never have called himself a “convert.” He simply (and not so simply) opposed all forms of religion that involved intellectual or political coercion and that did not make room for science and reason. It could not have been clearer from Adams’s correspondence with Thomas Jefferson during the last 14 years of their lives that the two men, despite their many political differences, were in fundamental agreement about religion. “We can never be so certain of any Prophecy,” Adams wrote to Jefferson in 1813,

or the fulfilment of any Prophecy; or of any miracle, or the design of any miracle as We are, from the revelation of nature ie. Natures God that two and two are equal to four. Miracles or Prophecies might frighten us out of our Witts; might scare us to death; might induce Us to lie, to say that We believe that 2 and 2 make 5. But We should not believe it. We should know the contrary.

A man like Adams, and thousands who moved from Puritan orthodoxy to liberal Protestantism or secular freethought (sometimes both) through rational reevaluation rather than mystical revelation, would never have been found trembling at flashing lights on the grounds of a revival meeting. Yet the split within the Puritan-descended churches that gave rise to Unitarianism and Universalism, in England as well as in the United States, was a conversion movement as surely as the revivalism that prompted farmers to pitch tents in muddy fields where preachers talked about salvation and damnation. Nevertheless, the liberalization of Protestantism was a long-term intellectual movement, not a sudden awakening—more like the modern transition to secularism from religious belief than the dramatic instantaneous religious conversions of the past.

Although the Unitarian-Universalist philosophy (if not the churches themselves) would prove well suited to the promotion of freethought on the frontier, the emotional revivalism personified by Cartwright found a larger and very different constituency in an antipodal position within the same unsettled society. What liberal Protestantism and evangelical fundamentalism had in common was their encouragement of individualism in religious thinking—whether that meant a personal relationship with God or personal doubt about the existence of any divinity. Self-educated men such as Lincoln learned to read from the Bible—usually the only book in their homes—and needed years to find and absorb the thoughts of other, nonreligious authors and integrate them with earlier religious teachings. People who had to work hard to acquire the basic materials for learning could not afford to cut the process short by embracing revelation while lightning flashed. Overnight conversions were so alien to the intellectual temperament that educated Americans (with some notable exceptions like William James) were inclined to dismiss even the most sincere accounts as inherently fraudulent.

Devout evangelicals on the frontier were as appalled by conversions to more intellectual faiths like Unitarianism and Universalism as they were by the overt anticlericalism beginning to be voiced by freethinkers. For fundamentalists, liberal Protestantism was often conflated with freethought and atheism. Cartwright tells the story of what he considered the disastrous conversion of the former Methodist preacher Beverly Allen, with whom he had boarded during the brief period of his childhood when he learned to read. Allen seems to have abandoned Methodism for Universalism after shooting and killing a sheriff because Universalism promised that all could be saved. Lo and behold, Cartwright, having undergone his own conversion and become a Methodist minister, was called to the bed of the dying Universalist. “Just before he died I asked him if he was willing to die and meet his final Judge with his Universalist sentiments,” Cartwright recounts. “He frankly said that he was not. He said he could make the mercy of God cover every case in his mind but his own, but he thought there was no mercy for him; and in this state of mind he left the world, bidding his family and friends an eternal farewell, warning them not to come to that place of torment to which he felt himself eternally doomed.”

This story of a Universalist’s deathbed abandonment of belief in universal salvation is an odd twist on the tales of atheists and freethinkers such as Voltaire and Thomas Paine, said to have made deathbed conversions to the orthodox religion they rejected in life. Actually, an abandonment such as Allen’s makes a good deal less emotional sense, since the Universalist was condemning himself, while a dying freethinker embracing some undefined form of faith would be hedging his bets. To exclude only oneself from God’s mercy is surely one of the stranger varieties of religious experience.

Neither did social toleration of conversion, on the frontier or in the East, extend to switches of faith from Protestantism to Roman Catholicism. Anti-Catholicism was a prejudice that united American Protestants of otherwise feuding denominations and very different social classes. Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton (1774–1821), like Cartwright, came of age in the new American Republic and was a religious convert—but that is all she had in common with the backwoods preacher. Born into a prominent Episcopal family in New York City, Seton converted to Catholicism in 1805, founded the American Sisters of Charity, and was canonized in 1975 as the first American-born saint. She was disowned by her Episcopal family, but the difference between the New World and the Old was that under the Constitution, her relatives could not use the power of the state to overrule their black sheep’s religious choice.

Even with regard to Jews—the scapegoats of Europe—devout evangelicals in the early Republic generally relied on out-arguing any challenge from the older faith. Cartwright describes a telling incident, not long after his own conversion, in which he and his fellow Methodists encountered a Jew who “was tolerably smart, and seemed to take great delight in opposing the Christian religion.” At one of Cartwright’s prayer meetings, “this Jew appeared” and told the Methodists that “it was idolatry to pray to Jesus Christ, and that God did not nor would he answer such prayers.” Cartwright asked him, “Do you really believe that there is a God?” Yes, the Jew replied. “Do you really believe that this work among us is wrong?” Cartwright asked. The Jew said he did believe that Christian proselytizing was wrong, and his response led to nothing more than an extended biblical argument. One can only imagine what might have happened had a Jew made such a comment at a Christian prayer meeting in contemporary Geneva, Frankfurt, or Lyon.

[adblock-right-01]

Nevertheless, American attitudes toward new religions, especially if they involved successful and determined proselytizers like Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Christian Scientists, ranged from suspicion to persecution. It is well known that after Joseph Smith saw a vision in a glade in Upstate New York in 1823 and received the gold plates with the Book of Mormon, the Mormons were driven out from one place after another—the plates were, conveniently, seen by no one but Smith himself—settling eventually in Utah.

Jehovah’s Witnesses—founded by Charles Taze Russell in 1872—were considered pests because of their aggressive personal proselytizing. The older negative view of this strange religion would morph into persecution at the beginning of the Second World War, when the Witnesses’ refusal to salute the flag or recite the Pledge of Allegiance led to vindication in one of the most important civil liberties cases in American history, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. This 1943 decision reversed a Supreme Court ruling issued only three years earlier, in which the court had upheld the right of schools to expel children who refused to recite the pledge. The earlier decision was associated with mob violence in which Witnesses were tarred and feathered. In Nebraska, one Witness was even castrated.

In the Barnette decision, Justice Robert H. Jackson, who later became the lead American prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trials, declared that “if there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

Part of the long-term hostility to the Witnesses was certainly class-based. They drew many of their converts from the poor and poorly educated; in most communities, it was a social disagrace for a family to lose a relative to what was perceived to be a fringe religion. This was as true within African-American churches as in predominantly white religious denominations.

Mormonism seemed to be a marginalizing type of new religion at first, but the church eventually showed its pragmatism by renouncing polygamy as a condition of Utah’s admission to the Union in 1896. Moreover, Mormons would become wealthy and politically influential as a result of generations of endogamous marriage and a culture that emphasized the importance of supporting other Mormons financially and socially.

Thus, the American majority’s negative reaction to the three largest new religions founded in the 19th century was based not so much on theological differences as on violations of social norms. Regarding Mormons, the issue was polygamy and, later, the heritage of polygamy. For the Witnesses, until World War II, hostility was generated mainly by their refusal to mind their own business concerning the religion of their neighbors. Christian Science, founded by Mary Baker Eddy in the 1870s, was something of a special case. At a time when doctors knew little more than their patients did about the causes of and cures for disease, the faith’s rejection of contemporary medicine did not seem wildly unreasonable. But as killer diseases began to succumb first to improved sanitation in the late 19th century and then to antibiotics and vaccines in the 20th, Christian Science increasingly looked like lunacy to potential converts.

One fundamental aspect of American civic life has never changed—the obligation to respect every religious and antireligious institution’s right to exist. Cartwright hated Universalism, and Elizabeth Seton’s relatives disowned her for becoming a Catholic, but the first American religious commandment (after the First Amendment, of course) emerged in the early republican era. The admonition goes something like this: “Thou shalt not pester thy neighbors about adopting whatever outlandish or downright repellent theologies they and thou art perfectly free to profess.” This unwritten commandment was and is a source of persistent tension within American society, since proselytizing, for many believers, is an integral part of their practice of religion. But the tension did not negate the huge difference between the rest of the world and the young American Republic, graced by a founding document mandating that citizens be free to follow their consciences regardless of majority opinion. That this fundamental principle has been violated many times makes it more, not less, important. The legal underpinning for the right to choose one’s faith, or no faith at all, continues to enable both the unusual American approval of religious conversion and the fierceness with which Americans sometimes turn against religions suspected of covertly or overtly undermining that freedom.