Baldwin the Prophet vs. Baldwin the Writer

Can a film really capture the essence of both?

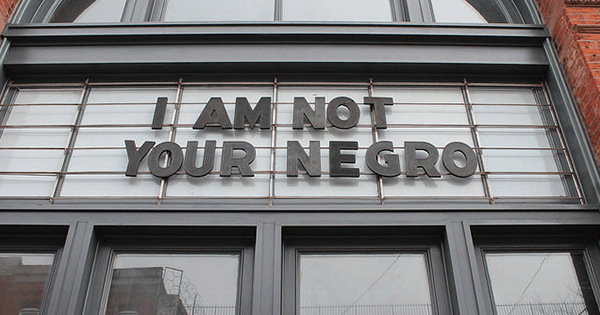

One of the most highly touted movies of this past year has been Raoul Peck’s documentary about James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro. Being a longtime lover of Baldwin’s prose, I snatched at the invitation to a press screening. While his first two novels, Go Tell It on the Mountain and Giovanni’s Room, are fine efforts, I am much more captivated by his essays, which seem to me miraculous and magical achievements. Quite simply, I regard him as one of America’s two or three greatest essayists. So I was especially curious to see this film, which purported to center on an unfinished book discovered in Baldwin’s papers, about three assassinated African-American leaders he had known, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King.

I say “purported,” because the fragmented text, or set of notes, is used as a hook at the beginning (we hear a few passages read aloud by Samuel L. Jackson) and soon disappears, giving way to a mash-up of quotes from other, more familiar works of his, footage from his public appearances, and news clips of more recent racial troubles. Peck is a skillful filmmaker, and he has put together a worthy introduction to Baldwin for the general public. I should not have been surprised that there was nothing new here for me, nor was it reasonable for me to have expected a commercially released motion picture to engage closely with an entire written text, and yet the archivist in me was frustrated and disappointed.

Baldwin is as ever a kinetic, charismatic presence onscreen, his mobile facial expressions signaling shades of intelligence, qualification, and nuance as he fields the questions by denser interviewers or eloquently rebuts statements by blustering fellow panelists. His dark suit, white shirt, and thin black tie (the preferred uniform of ’60s jazz musicians) have an elegance and dignity that complement his half-boyish, half-worldly grin or smoldering looks of outrage. That’s the given. The problem, for me, is that Jimmy the public figure begins to subsume Baldwin the writer. As he became famous, he was sought out to explain to white audiences the reasons why blacks were fed up or rioting, and he gave in to a pundit’s warnings and prognostications. By juxtaposing Baldwin’s rhetorical pronouncements with footage of recent police carnage and African-American unrest, Peck is freezing him in the role of prophet and making him the posthumous “witness” and spokesman for our current racial malaise.

Yet how good a prophet was he, in fact? And what effect might this public persona have had on the quality of his writing in the second half of his life? In addressing the first question, I find many of his predictions overblown. The apocalypse of radical revolution he predicted in The Fire Next Time did not come to pass, nor—given the resiliency of the American capitalist system, like it or not—is it apt to occur now. He also tended to make dubious negative statements, such as accusing whites of being responsible for the death of Malcolm X, or saying that they are lacking in the sexuality-spontaneity department, to which I would respectfully demur. We do him no favors as a thinker to accept unquestioningly every statement he made. He has certainly become a useful heroic symbol for expressing our contemporary dismay at the persistence of racism, and a corrective to American complacency, and perhaps that should be enough. But being preoccupied with the essay form, I can’t help wanting to understand better his arc as an essayist. The film, by running together quotes from different stages of his life, without distinguishing their dates of composition, makes Baldwin out to be always in command, a consistent oracular figure, not subject to the vicissitudes and blockages of every writer.

I felt reluctant to state aloud my reservations about the film, especially to those who loved it, and was even a little ashamed of myself for having them. Then I came upon a review of the picture by James Campbell in The Times Literary Supplement, which expressed similar misgivings. Campbell, a Scotsman and currently a TLS staff member, has written a superb biography of Baldwin; he had had personal dealings with the writer as his editor and knows the man’s story inside-out. He questions the film’s title credit, “written by James Baldwin,” which he thinks would have been better characterized as, “Script derived from texts by…” Pointing out the uncomfortable fact, never mentioned in the movie, that Martin Luther King distanced himself from Baldwin because of the latter’s homosexuality, Campbell makes this bold assessment:

The assassination of his three heroes caused a rupture in Baldwin’s nervous system and stalled the flow of ink in his prose. ‘I didn’t know for a long time whether I wanted to keep writing or not,’ he said later. ‘What I said to myself was that Martin never stopped. So I can’t either.’ In fact, he published many books after 1968, but the fluent prose of his early essays, incorporating memoir and moral philosophy—the prose of ‘Notes of a Native Son,’ ‘Equal in Paris,’ ‘The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy’ (about his relationship with Norman Mailer), ‘Down at the Cross’ and others—was gone. It had been sustained by a morale based on the belief that ‘we, human beings, can be better than we are.’ The bullet that killed King riddled that morale and put the validity of optimism in question.

Now, I agree completely with Campbell’s assertion that Baldwin’s writing after 1968 lost its magic. I just think he’s giving him too noble an excuse by saying the diminishment occurred because he was disillusioned by the world’s violence. Baldwin needs no excuse for his books falling off in quality: even the finest writers frequently do not sustain their best efforts over a whole lifetime. That’s not a shame, or a scandal, but the most normal thing in the world, especially for a writer like Baldwin, whose early gift was akin to that of a lyric poet; and lyric poets tend to burn out once they hit middle age. In his later years, Baldwin kept accepting advances for book projects that he couldn’t complete; he procrastinated, not necessarily from the response to American racism (he had been living in Europe at that point for decades), and those projects he did complete often ended up digressive messes with some beautiful passages scattered here and there. Such dogged if doomed efforts in the face of artistic decline have their own heroic dimension. I Am Not Your Negro does not come close to touching that drama, but its inclusion, in my opinion, would have made for a more interesting or at least more honest movie.