In my early 20s, having received an MFA in creative writing from Brown University, I sought to cobble together a living by teaching. Although I had taught an undergraduate class as part of my fellowship, I hadn’t yet published a book, so the only such work available to me was intermittent and, often, unconventional. I spent the first summer after I graduated not working with words but performing the same kind of maintenance and handyman tasks that had helped pay for college—this time for the university from which I had just received an expensive degree. Some of the rooms I cleaned and refurbished had recently been vacated by the students I had just taught.

As my summer maintenance work came to an end, I found a part-time job teaching creative writing at the state prison in Cranston, Rhode Island. Twice a week, I’d drive to Max, as the maximum-security facility was known, a three-story gray-brick building that was topped by an imposing green cupola and surrounded by razor wire. It had been built in the 1870s and expanded several times since, but little seemed to have changed since the 19th century except for the gates, which were now operated by electricity. I would park behind a chainlink fence and, upon entering the building, place everything except my teaching materials in a locker. Then I’d present my credentials to the first of many guards whom I would encounter on any given day.

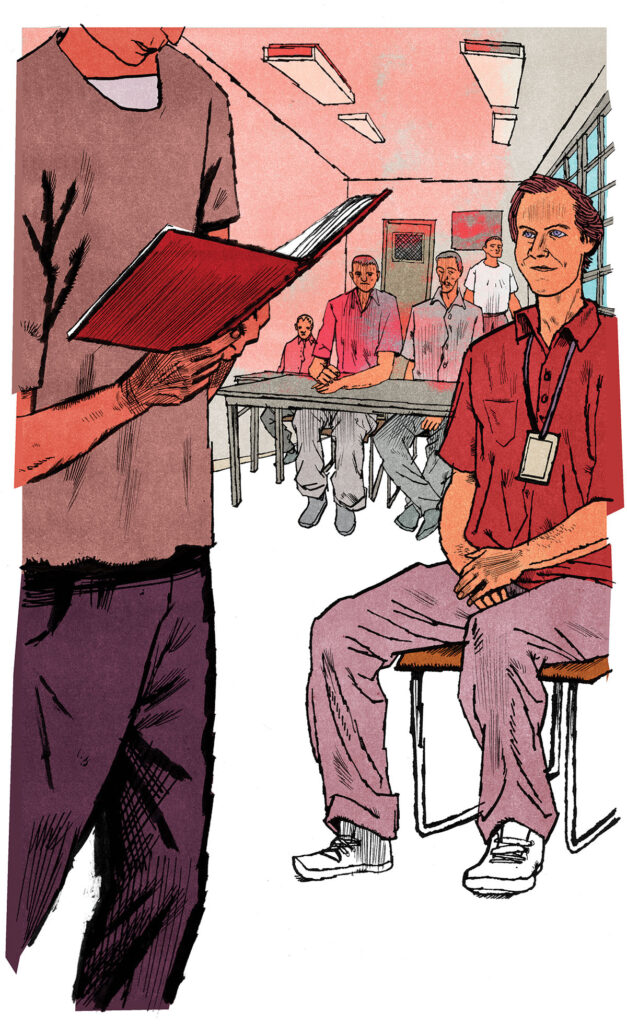

The inmates were suspicious of me at first, asking whether I was there “to observe the animals” or betting that I would simply stop showing up, as had so many of their previous instructors. The prison officials did their best to contribute to this attitude, telling my students that I hadn’t arrived that first day, when I was already sitting in the classroom waiting for them, or deliberately delaying me so that I would be late. Sometimes they would ignore me when I presented my teaching ID; other times, they would let me through one set of rolling, barred gates, only to leave me trapped before the next set of gates while the warden wandered off to get a cup of coffee. But I persisted. And though the inmates gradually began to accept that I could be relied upon and didn’t have a hidden agenda, I was still a puzzle to them.

“You talk funny,” one man said to me.

“Well, I’m from South Africa.”

“What the hell you doing in this dump?” he asked.

I explained that I earned $20 an hour doing this gig and needed the money.

Before I started working there, my girlfriend had visited the prison with the previous instructor, thinking she might take the position. She had been advised to say she was married, and she wore her grandmother’s ring as proof. (She passed on the job after a warden and the writing instructor regaled her with lurid details about the crimes some of the men had committed.) When one day I inadvertently referred to her as my girlfriend, one of the guys yelled out: “That chick, A—, who came here with Wacky Joe? She said youse guys were married.”

“Yeah, I know. She did that so no one would hit on her.”

They seemed happy that I gave an honest answer, though one man told me: “You tell your girlfriend that it ain’t nice to lie to people.”

A beefy prisoner wearing a coat that resembled a duvet, enhancing his resemblance to the Michelin Man, added: “You’re smart. I wouldn’t let my woman hang around this riffraff.”

The classes took place in the educational wing, its sparse collection of books—mostly dictionaries and an encyclopedia—earning it the title of prison library. The wing was run by an affable and intelligent guard who clearly cared about the inmates; he had bought them a coffee urn with his own money and done what he could to liven up the area under his charge. He was also a former Golden Gloves boxer who would occasionally challenge an obstreperous student to step in the ring with him, and the inmates treated him with respect.

The previous teacher (the one they called Wacky Joe) had distributed copies of a short-fiction-anthology-cum-manual by one of my own teachers at Brown: R. V. Cassill’s Writing Fiction. I continued using the anthology for a while, and I gained some cachet by arranging a visit from the anthologist himself. I also brought stories that seemed suitable for brief in-class assignments, having realized that many of the inmates were hyperactive and had short attention spans. My prompts were intended to allow someone to write a poem or anecdote in 20 to 30 minutes. For example: “Write a tall tale, where you present something obviously untrue in a way that makes it believable.” This was a favorite exercise, since the inmates had already read Mark Twain’s “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” I also suspected that they had practice coming up with plausible falsehoods. One writer invented a clever explanation for his lack of hair: he’d been attacked by bald eagles while hiking in the Sierras—the eagles had needed hair for their nests.

One day, I brought in a favorite book on teaching poetry—Kenneth Koch’s I Never Told Anybody—and said that I would like to share some of the responses from a workshop that my girlfriend and I had conducted in the local old-age home.

“You teach in an old-age home?” said Angel, a powerfully built man who was in for bank robbery. “Boy, that must be depressing.”

I looked around at the barred windows of the educational wing, probably the nicest space in the whole prison. “I suppose,” I said, “but poetry can make you forget your surroundings.”

“Nothin’ can make me forget these surroundings,” Angel muttered. “But, geez, sitting around in one of those places, waiting to die.”

Louis, a lean older man, snorted. “You think this is different, Angel?” He had been on death row until the Rhode Island Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional. He was also a good deal smarter than most of the other inmates and didn’t mind letting them know it. Louis wrote stark, accomplished poems that would have gotten him into any MFA program in the country, but he was dismissive of the value of his own talents. His usual comment on the published stories we read was, “Bullshit! Just another scam.”

I read a poem by an elderly man in our workshop at the old-age home. It described the death of his mother when he was five. He and his father had embarked on a journey by donkey cart lasting several days until they got to a town with enough Jewish men to form a minyan.

For once, Louis was impressed.

“This guy is, what, 100 years old, and he still misses his mom?” he said. “That’s something.”

There often weren’t enough copies of the anthology or handout to go around, so I generally read a story aloud before we discussed it. One day, I opened a book at random and said, “How about Sartre’s ‘The Wall’? That’s a good story.”

Angel, whose biceps were as thick as my calves, snatched the book out of my hands and declared, “I’ll read it. You’re always reading to us, and I’m tired of it!”

He read aloud in a steady monotone, like a diligent middle-schooler, his voice free of emphasis or inflection. He rarely paused, just read steadily with the same weight on every word, sweat making his head gleam even more than usual. I had time to observe the other men’s faces and wondered if I’d made a big mistake. At least two other men in the room, aside from Louis, had been on death row. And here I had chosen a story set in the Spanish Civil War in which the narrator, Pablo, and his companions are passing a slow, terror-filled night, waiting to be shot in the morning.

The story delves into their involuntary physical changes as the hours pass—they know that death is imminent, and their bodies react to the knowledge of their fate no matter how hard they try to think of something else. Sartre dwells on the condemned men’s hatred of the doctor who is observing them, a man who will go home to his familiar comforts in the morning, enjoying food and drink and a soft bed after the narrator and his comrades have ceased to exist. As Pablo says,

My life was in front of me, shut, closed, like a bag and yet everything inside of it was unfinished. For an instant I tried to judge it. I wanted to tell myself, this is a beautiful life. But I couldn’t pass judgement on it; it was only a sketch; I had spent my time counterfeiting eternity, I had understood nothing. … Death had disenchanted everything.

There was absolute silence in the room other than Angel’s droning voice. The men stared fixedly at him; even Louis had dropped his habitual air of bored abstraction. There was none of the restless moving about, the fidgeting, the jumping up to refill a coffee cup, nothing to suggest that I was in a room full of students with limited attention spans. I had last read the story for a college philosophy course, our discussion remaining abstract and centering on the ways in which the narrative illustrated the principles of existentialism. We were young, and the thought that death could be imminent and should inform how we live meant little to us. Now, Pablo’s words rang true—I had understood nothing.

“The Wall” has a surprise, O. Henry–style ending. The narrator is kept alive and waiting while each of his companions is taken outside and shot. After a while, he is led into a room where two officers ask him about the whereabouts of an important revolutionary figure, Ramon Gris. Pablo knows where Gris has been hiding but has no intention of revealing the truth to his captors. He no

longer cares about life or death, and out of this indifference, just for laughs, he makes up a different location and watches with amusement as the officers prepare for a task he is sure will be a waste of time. Unbeknownst to him, Gris has left the safe house and is now hidden in the graveyard digger’s shack in the cemetery, the very location Pablo identifies. Gris is killed in a shootout with Franco’s soldiers.

After reading the final sentence, Angel hurled the book across the room.

“Goddamn it,” he yelled. “I hate that stupid ending. Listen, Teach, you better get hold of this Sarter dude and tell him to come up with an ending that isn’t a pile of horse crap.”

An inmate known by the state he was from, Tennessee, slammed both his fists on the table and shouted, “Why’d he do that? Why’d he ruin it?”

Louis looked at me with his cold killer’s eyes, watching me react to the men’s anger and adrenaline. There would be no talk about “craft” today, just a visceral response to feeling cheated.

“It was good until that last page,” Louis said. “And then …” He shook his head. “Bullshit. Another scam.”