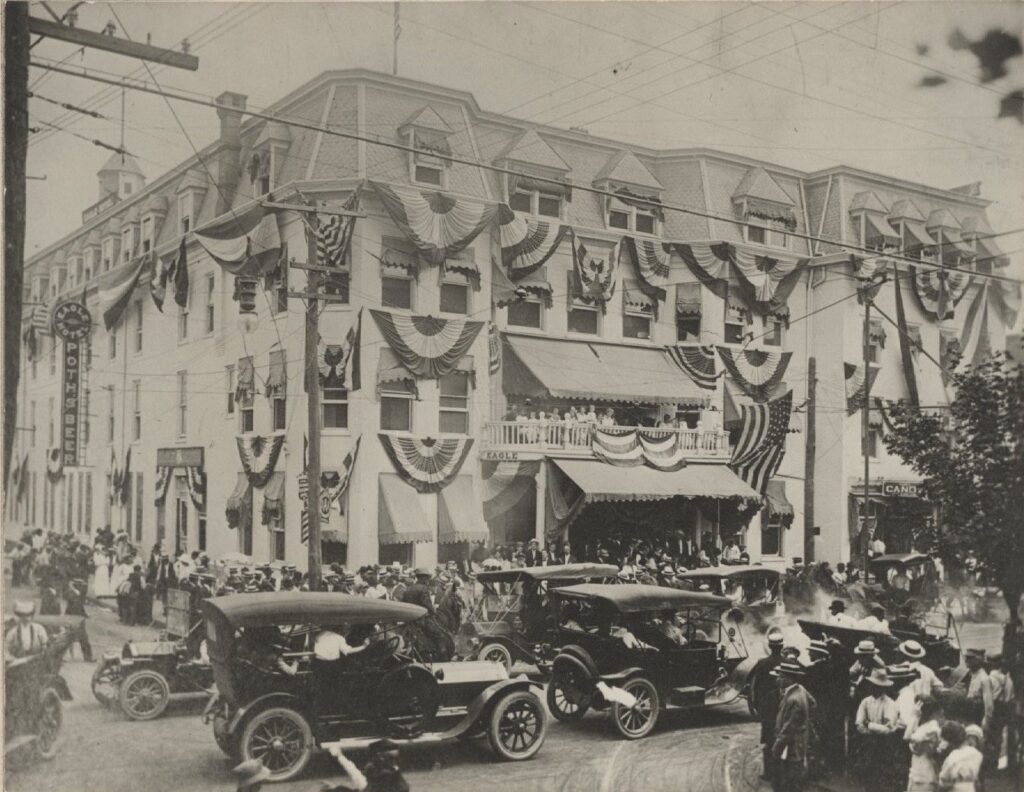

Surely one of the most peculiar letters ever written by an American composer came from the hand of Charles Ives in July 1913. For one thing, it was written on the letterhead of the Eagle Hotel in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the same Eagle Hotel that, 50 years before, had been the temporary headquarters of Major-General John Buford at the outset of the fighting in the greatest of all battles of the American Civil War. But there was more oddness to the letter than just its heading, beginning with the fact that Ives arrived in Gettysburg just as massive celebrations marking the battle’s 50th anniversary were beginning. The little crossroads town was playing host, from June 29 until July 6, to 44,713 Union veterans of the battle, alongside 8,694 Confederate veterans, in a great reunion celebration whose most famous participants were Union General Daniel Edgar Sickles (who lost a leg at Gettysburg) and President Woodrow Wilson. Moreover, Ives was there in the company of his father-in-law, a Union veteran who had served at Gettysburg. And it only got stranger from there. Writing to his business partner, Julian “Mike” Myrick, Ives related how “[w]e’re having a wild, busy, and hot time of it.” Ives even found himself “appointed bodyguard to Gen. Sickels, as his cussing keeps the ladies away.” After a few days of this, Ives was itching to escape back to his home in West Redding, Connecticut, where he would then “try to settle down.”

All of which begs the obvious question: What was Charles Ives doing at the Gettysburg 50th reunion, and especially as a “bodyguard” for the notorious Dan Sickles?

A large part of the answer to that question lies in correcting a basic misperception of Ives’s place in American music. In the seven decades since his death, Ives has frequently been pigeonholed as “the first major American modernist,” and even Aaron Copland would describe Ives’s Central Park in the Dark (1907) as “musical cubism.” Yet no one would have rejected—and did reject—the modernist label with more curmudgeonly vigor than Charles Ives. Modernist pretenses to live in abstractions left Ives cold (just as Ives’s music left many of the modernists cold). Instead, his music (said the violinist Jerome Goldstein after playing the premiere of Ives’s Second Violin Sonata in 1924) was the echo of New England “in all its glory and bigotry,” brimming with “pages of revival meetings, Boston Tea Parties, boiled dinners, and those innumerable inrushes of the soul which Emerson received—or said he did.” Amelia Ives Van Wyck remembered that her cousin

would sit down and play something, and he’d say, “What is that?” I remember once I said, “it sounds like Sunday in the country.” And he said, “That’s just what it is.” It was part of the Concord Sonata, I think. To another one I said, “That sounds like a storm at sea.” And he said, “No it’s in the mountains.”

Much as Ives deployed all manner of experiments in polytonality, polyrhythms, and dissonance, he did so, as Goddard Lieberson shrewdly noticed, “not out of a sense of modernism or out of a sense of avant-gardism … but out of a kind of necessity,” a necessity generated by his passionate longing to re-create the small-scale, slow-speed, golden-filtered memories of his youth, a youth in which no event had more power than the American Civil War. Within that longing, Ives would build musical tributes to his father, a Civil War bandmaster; to the Union cause whose everyday music permeates his songs and his violin sonatas; and to the moral imperative of emancipation, which he celebrated in his Second Symphony and, at its highest pitch, the first movement of Three Places in New England. Far from an oddity, Ives in 1913 could have been in no more significant place than Gettysburg.

Charles Edward Ives was born in Danbury, Connecticut, in 1874, almost a decade after the close of the Civil War. But the memories, influence, and impact of the war hung thickly in the atmosphere of small-town western Connecticut, as indeed it could hardly have been otherwise. Overall, Connecticut sent some 55,000 men into the Union ranks during the Civil War, almost a quarter of its white male population; 1,100 of them enlisted from Danbury in just the first two years of the war, including Ives’s father, George Ives. When Nelson White, the lieutenant colonel of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, returned to Danbury on recruiting duty in September, 1862, he signed up the 17-year-old George Ives as bandmaster for the regiment, and Ives built it into what Ulysses Grant once called “the best band in the army.”

George Ives went on to become Danbury’s principal town musician, and he inculcated into his son Charles a taste for experimenting with sound—with the cacophony of rival bands marching past each other, with songs sung to accompaniments in a different key, with amateur singers whose earnestness was more valuable than the steadiness of their intonation—and Sidney Cowell was not far from the mark when she wrote that “the son has written his father’s music for him.” But George Ives’s Civil War career held a special place of honor in the younger Ives’s mind. Lehman Engel, the Broadway conductor and composer, remembered that Ives “always talked about Pa and Lincoln as though they were two people that one met every day on the street,” and especially about “what Lincoln said to Pa and what Pa said to Lincoln.”

Still, as vital as George Ives was to his connections to the Civil War, Charles Ives had another, almost as important, connection to the war through his father-in-law, Joseph Hopkins Twichell, “a fighting chaplain of the Civil War,” and it was the Twichell connection that brought Charles Ives to Gettysburg in 1913. Fifty-two years before, as a 23-year-old divinity student at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Twichell had signed himself up as chaplain to the 71st New York Volunteers, one of the five regiments of the so-called “Excelsior Brigade” in the Union’s Army of the Potomac. The brigade’s chief recruiter and overall commander was the raffish New York politician Daniel Edgar Sickles, who only three years before had shot to death his wife’s lover, Philip Barton Key. Sickles had beaten the murder charge on a plea of temporary insanity, and in a bid to restore his tarnished political fortunes, crossed the political aisle to support Abraham Lincoln’s Republicans in the Civil War.

When Sickles wangled a commission as brigadier-general of the Excelsior Brigade, Twichell was at first suspicious of him. But when he heard Sickles address the brigade in May 1861, every doubt about Sickles’s innocence and sincerity unwisely vanished. Even though Sickles nearly cost the Union army the battle by thrusting his troops far to the front of the Union position at Gettysburg, Twichell was convinced that Sickles “had been the master-spirit of the day and by his courage, coolness and skill had averted a threatened defeat.” Fifty years later, the elderly Twichell arranged to rendezvous with his 93-year-old one-time commander in New York City, and travel from there to Gettysburg for the great reunion. Fearful for her father’s health, Harmony Ives beseeched her husband to accompany her, Twichell, and Sickles to Gettysburg, and as a group, they set up temporary residence at the Rogers house, within view of the spot on the Trostle Farm where Sickles had been shot. And Charles Ives became Sickles’s unlikely “bodyguard.”

But it was not just Ives’s family connections that attracted him to the Civil War: his four years at Yale in the 1890s also surrounded him with the shadows of the conflict. Yale gave more than 700 of its alumni to the Union cause (and 114 of them died), and as early as 1865, Yale was tinkering with plans for a Civil War memorial on campus. The anti-slavery Hartford parson, Horace Bushnell, spoke then of how the war had not merely reunited a divided nation, but had also become “the tide swing of a great historic consciousness” that would aid Americans to “define our own canons of criticism” and yield “incident enough to feed five hundred years of fiction.” And with what might have been an anticipation 30-years-on of Charles Ives, Bushnell asked, “Are there no new singers to meet that great era? None who shall do it full justice?”

It was a question Charles Ives would spend much of his life answering, in music. His composition teacher at Yale, Horatio Parker, gave him the basic tools and skills of composing. But Parker was also dismissive of the thematic materials with which Ives had grown up in Danbury—marches, camp-meeting hymns, ragtime—and Ives would remember that, by the time he graduated from Yale, “he was in open revolt against the Yale music department.” It would become Ives’s mission instead to use unusual “sound and rhythm combinations” from the American vernacular to capture the spirit of the camp meeting, or “the excitement, sounds and songs across the field and grandstand” at a football game—something “you could not do … with a nice fugue in C.” Those “combinations” would also shape the way he rendered the Civil War into sound.

To Charles Ives, the Civil War would never be less than what Stuart Feder called “Ives’s War of Wars.” It became “the most important event in history,” a shining moment of moral truth, sanctified by the memories of his father (who died just after Ives departed for Yale and who left Ives with nothing “to fill up that awful vacuum”), the energies of New England abolitionists, and Lincoln’s emancipation of three million slaves. The compositions he wrote to remember it are all lavish demonstrations of a determination to use the American past to understand its present.

The 114 Songs offers the broadest entrance into Ives’s remembrance of the Civil War, since so many of the songs reach for the raucous and unrefined music of Civil War military bands. “He Is There!” is an unapologetic tribute to the American doughboy of World War One who “fifteen years ago” had marched “beside his granddaddy / in the decoration day parade”— which was as much as to say that the grandfathers who served in the Union Army had exemplified the military virtues the grandsons would need in 1917. If the words were insufficient to make that point, the music would. In Ives’s imagination, “the village band would play those old war tunes, and the G.A.R. would shout … as it sounded on the old camp ground”—all to the tune of Walter Kittredge’s “Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground” and George Frederick Root’s “The Battle Cry of Freedom.” It was an important way of connecting the American past with the crisis of the Great War in the present, as the “boys” marched off to ensure that Lincoln’s old motto of “liberty to all” was still carried forward as “Liberty for all.”

“He Is There!” in 1917 is only the most obvious of Ives’s messages from the Civil War. He had already composed (and at approximately the same time as his visit to Gettysburg) “Old Home Day,” which after a dreamy introduction, begins a 4/4 march beat “along Main Street” of a “‘Down East’ Yankee town.” The pace is set by “the ‘3rd Corps’ fife”—and was it an accident that Dan Sickles had commanded the 3rd Corps of the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg? Snatches of Julia Ward Howe’s “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” now “rouse the hearts of the brave and fair,” while the repeat adds another “fife, violin or flute” obbligato with “The Girl I Left Behind Me” and the Irish Brigade marching tune “St. Patrick’s Day in the Morning.” But nothing else in the 114 Songs quite rises to a pitch of Civil War enthusiasm as much as the solemn “Lincoln, the Great Commoner” (a setting of Edwin Markham’s 1900 poem “Lincoln, the Man of the People”). The introduction brings forward phrases from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” (which are then repeated six measures from the end), but also “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” “Hail, Columbia, Happy Land,” “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.” At the end, the final cadence is a phrase from “The Star-Spangled Banner”—as though Lincoln was summation of American identity in general.

If the 114 Songs contain the widest samples of Civil War musical echoes, it is Ives’s instrumental and symphonic works that contain the clearest intellectual and cultural messages from the war. Some of this was surely tied to his memories of George Ives, “memories of an old soldier, to which this man still holds tenderly,” as he wrote in the epilogue to Essays Before a Sonata. But another part served as Ives’s endorsement of what Barbara Gannon has called “the Won Cause,” the persistent loyalty of both white and black Union veterans to the memory of a war that was caused by slavery, fought over slavery, ended with the destruction of slavery, and pointed all Americans toward a society that erased the “badges of slavery or servitude.” And it was surely no accident that Ives, as the son of a Connecticut veteran, caught more than a little of the close connection that Connecticut veterans like George Ives made between their wartime service and emancipation. As Gannon has shown us, Connecticut’s 20-odd volunteer infantry regiments spent most of their time on battlefields outside the large-scale campaigns of the war, and, significantly, in close contact with the peripheral battles fought by the new Black volunteer regiments at Olustee, Charleston, and Port Hudson. And in the years after the war, Connecticut veterans organized Grand Army of the Republic posts with no color lines: “We have no separate posts here,” reported one newspaper, “as colored and white are united.”

The particular accents of this kind of memory can be seen clearly in the movement Ives entitled “Decoration Day” (the modern Memorial Day) from the orchestral set New England Holidays, most of which he likely composed between the Gettysburg reunion and 1915. From its languorous, quadruple-piano opening, the dream world of that “early morning” emerges slowly, until the flute, the bassoon, and then the horns introduce Henry Clay Work’s “Marching Through Georgia”:

Bring the good old bugle boys, we’ll sing another song

Sing it with a spirit that will start the world along ….

Then, a low, steady marching beat begins, under a distant quote from “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and “Tenting Tonight,” as a memorial parade to the town cemetery forms up. When the cemetery is reached, the trumpets introduce “Taps” (along with “Nearer, My God, to Thee” in the strings) as a reminder that this is intended as a tribute to fallen Union soldiers. The band that led the procession to the cemetery now strikes up the 6/8 rhythm of David Wallis Reeves’s “Second Regiment Connecticut National Guard March,” and with the march’s final cadence, the band stops, the strings return to the mood of reverent quiet, “and the sunset behind the West Mountain breathes its benediction upon the day.” And as if to leave no doubt about the particular message “Decoration Day” was intended to highlight, Ives originally added “Abolitionists” to the title. The marches remind the listener of George Ives the bandmaster; as specifically Union marches, they also single out the “Won Cause” as the object for which George Ives and his peers struggled.

Civil War tunes also have a role in Ives’s smaller instrumental works (especially the first two violin sonatas, where Ives set himself the task of “trying to relive the sadness of the old Civil War days”) and even more, in his largest symphony, the Second, which Ives probably composed, for the most part, between 1902 and 1909, drawing at times on older material. The echoes of the Civil War are audible in the symphony’s first movement with “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.” But much more dramatic is the quick introduction, at the outset of the second movement, of Henry Clay Work’s 1864 abolitionist song “Wake Nicodemus,” where the powerful slave character, Nicodemus, foretells the coming of freedom:

But he long’d for the morning which then was so dim—

For the morning which now is at hand.

“Wake Nicodemus” is only slightly more prominent than Stephen Foster’s tune “Massa’s In The Cold, Cold Ground” (at a time when Foster’s writing was still thought to be a record of real plantation songs of the slaves), followed by hints of “Columbia” (in the brief fourth movement), a faint reference to “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” and finally another Foster lament, “Old Black Joe” (which Ives believed embodied “the Days before the Civil War” and “reflects this country’s days of fret storm & stress for liberty,” as well as Foster’s “sadness for the slaves”). What should also not be missed is the consistent message of the wartime themes he uses: the awakening from slavery to freedom, the burial of the Old Massa in the “cold, cold ground,” the celebration of “Liberty’s form” in “Columbia.”

Nothing, however, in Ives’s oeuvre captures so thoroughly Ives’s fascination with the Civil War as the first of the three movements of Three Places in New England, which he began working on in 1912 and scored in 1914—on either side of the Gettysburg reunion. That movement is clearly devoted to a musical portrait of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s famous 1897 monument on Boston Common to Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers—the first Union regiment to be recruited from Black state volunteers once the Emancipation Proclamation had sanctioned Black enlistment in the Union armies.

The movement, which Ives entitled “The ‘St. Gaudens’ in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment),” carries a brief poetic preface, written by Ives himself:

Moving,— Marching— Faces of Souls!

Marked with generations of pain,

Part-freers of a Destiny,

Slowly, restlessly—swaying us on with you

Towards other Freedom!

The man on horseback, carved from

A native quarry of the world Liberty

And from what your country was made.

You images of a Divine Law

Carved in the shadow of a saddened heart—

Never light abandoned—

Of an age and of a nation.

Above and beyond that compelling mass

Rises the drum beat of the common-heart

In the silence of a strange and

Sounding afterglow

Moving,—Marching—Faces of Souls!

The “Saint Gaudens” begins with slow-moving figures, mostly in the strings, followed by a hint of the Stephen Foster song “Old Black Joe” and its repeated promise, I’m coming, I’m coming, in the oboe—which, if the Shaw Memorial is any guidance, describes the oncoming column of Black soldiers who parade nobly and intently alongside Colonel Shaw on the monument. The lower strings march up the scale, and amid other wisps of melody, I’m coming is heard in the oboe and the clarinet interjects a syncopated tune. Then, the first clear fragment of “The Battle Cry of Freedom” is heard in the flute (and especially the phrase the Union forever).

The pizzicato beat becomes more agitated, then settles into a slow march, signaled by a steady pattern in the percussion. Above them, the violins play the chorus of “Marching Through Georgia” (Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee! Hurrah! Hurrah! the flag that makes you free!). The pace picks up (with what Ives calls “a lithe springy step”) as the strings play ragtime figures over the march rhythm, bringing to life what Ives imagined as the songs of the Black soldiers of the Union army. With rising figures from “Marching Through Georgia” punctuated by a fanfare, the music builds to a peak, falls away, then builds again to a climax. The violins burst out with a cry joined by an eruption from the brass, as though Ives wanted the trumpets to sound the charge for the 54th Massachusetts’ courageous but ultimately unsuccessful attack at Battery Wagner on July 14, 1863.

And then, the strings and timpani return to their somber, dark march, and—in one of the most heartrending musical evocations of the suffering of the war—the flute joins them, softly playing the chorus of “The Battle Cry of Freedom” (While we rally round the flag, boys, we rally once again / Shouting the battle cry of freedom!). A few more wisps of Civil War melody, and the marching rhythm slowly fades to a close.

Over the course of approximately nine minutes, Ives manages to assemble a portrait of ineffable sadness and nobility, of a great cause whose costs were beyond the imagining of those who had marched so gaily to war in 1861. Saint-Gaudens’s monument, as David Blight has written, “is a narrative of tragedy.” Shaw and his men, resolute and forward-bending, are headed toward a sacrificial denouement at Battery Wagner, and Ives catches the moment with the use of “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” set above mournfully dissonant D major chords in the strings. The monument is not about wistfulness, or a triumphal celebration of eventual Union victory; and neither is Ives’s “Saint Gaudens.” They march forward together, and their message is sacrifice, uplift, and emancipation.

Charles Ives’s Civil War was about three issues, beginning with his homage to his father, and perhaps even to his father-in-law, Joseph Twichell. The second of these issues was the legitimacy Ives lent to the use of American vernacular music in serious composition. But the third issue was Ives’s conviction that using the vernacular had to serve more than a merely decorative purpose. In Essays Before a Sonata, Ives granted that “a composer born in America … may be so interested in ‘negro melodies’ that he writes a symphony over them.” The problem with mere usage of “negro melodies” was, for Ives, that composers might dabble in such usage as dilletantes, rather than being “interested in the ‘cause of the Freedmen.’” If a “composer isn’t as deeply interested in the ‘cause’ as Wendell Phillips was, when he fought his way through that anti-abolitionist crowd at Faneuil Hall, his music is liable to be less American than he wishes.”

The Civil War was for Ives a living cause, the cause of emancipation. This at a time when American writers were either glamorizing the Confederacy and Jim Crow (from Augusta Jane Evans to Thomas Dixon), politely accommodating Southern sensibilities (the American Winston Churchill in The Crisis), or feeling sorrowful for the price northerners had paid (in William Dean Howells’s The Rise of Silas Lapham) and pretending that the Civil War had been about something other than slavery. In Ives’s use of Civil War songs and marching music, the war served as both the substance for musical development and as a symbol of certain eternal verities—about freedom, about race, about the American experience itself. The Civil War music he embedded in his songs and symphonic works were starting points, not afterthoughts, much less amusement. Especially in the “Saint Gaudens,” his uses of Civil War music are not meant to entertain or impress, but to draw the listener into the ideals of the conflict itself, the world of Danbury in the full bloom of abolitionist energy, a world that, through his music, he could ensure would never be lost.