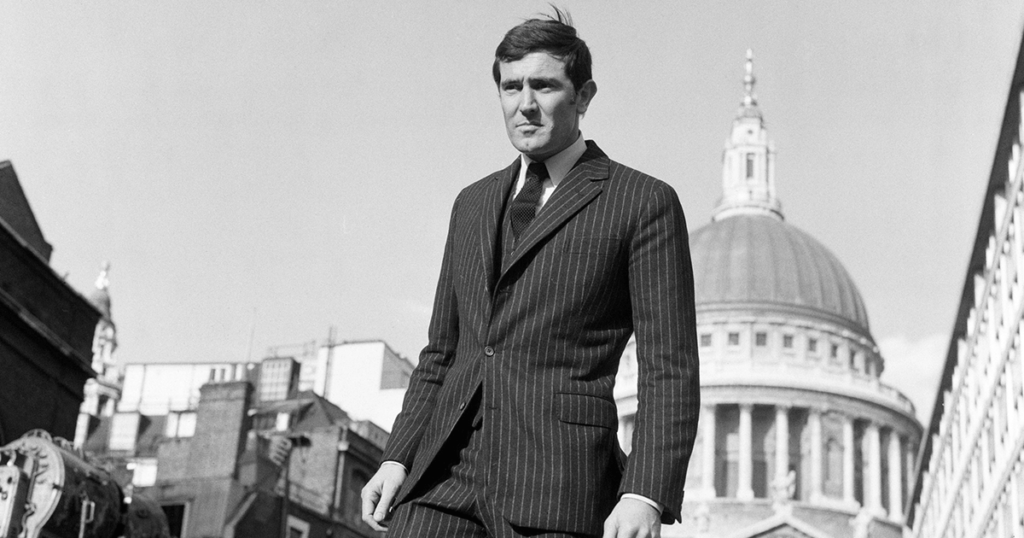

Two weeks ago, Thomas Vinciguerra published an article in The New York Times in praise of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, arguing that the movie ought to be recognized as one of the finest in the James Bond canon. Several friends of mine mentioned the article, having heard me, time and time again, make a case for this often overlooked film. To my taste, it isn’t even close: On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is the best Bond movie, even if it features the weakest Bond actor (George Lazenby, who had the seemingly impossible task of replacing Sean Connery). It’s stylish, emotionally layered, finely written, and filled with beguiling Alpine and Portuguese locations. Nowhere else is 007 so vulnerable, so human, and in no other picture is a Bond Girl as complex, independent, and formidable as Diana Rigg’s Tracy di Vincenzo. Among the movie’s most beautiful scenes are two that are distinctly un-Bond-like—the ending, for one, so utterly heartbreaking and unexpected, and the earlier montage depicting Bond’s courtship of Tracy, with Louis Armstrong singing “We Have All the Time in the World” in all his heartfelt, gravelly splendor. Armstrong was ill at the time, and he would die less than two years after the film came out, so that particular scene takes on, with the passage of time, an extra, poignant irony.

The reason I mention the film here, however, is because of another scene, one that makes use of a technique that I have always associated with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

A pivotal moment arrives about half an hour into On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, when the head of British intelligence, M, seems to lose faith in Bond’s ability to kill Ernst Stavro Blofeld and decides to take him off the mission. In a fit of pique, Bond has Miss Moneypenny draft a letter of resignation, then heads to his office to pack a suitcase. Opening his desk drawer, he begins pulling out, one by one, a series of objects that we recognize from previous Bond films. As he gazes nostalgically at these souvenirs from past adventures, we hear an accompanying snippet of music from their respective movies. First comes the knife belonging to Honey Ryder in Dr. No, as the familiar tune plays: Underneath the mango tree / Me honey and me can watch for the moon … Then we see the wristwatch with the hidden garrote that Bond uses to kill SPECTRE assassin Donald Grant, and as he pulls out the deadly wire, we hear a bit of the theme song from From Russia With Love. Finally Bond inspects a small underwater breathing device used in Thunderball, to the accompaniment of a few jazzy bars from that movie’s score. All of those films, of course, starred Connery, and this scene is meant to pay homage to the past before, in a way, dismissing it, to clear the decks for something new—a new Bond actor, a new adventure, a new era. This is precisely what Beethoven does so brilliantly in the last movement of the Ninth.

Beethoven, who wrote the Ninth Symphony while almost totally deaf, knew very well the degree to which he was breaking musical ground, in terms of structure, emotion, harmony, and scale. The first three movements are all magnificent: the opening Allegro—commencing with 16 hushed and amorphous bars that culminate in an explosion of sound—full of rage and tenderness; the Scherzo both expansive and propulsive; and a theme-and-variations Adagio that is one of the most heavenly things Beethoven ever wrote. Yet as grandly conceived as these movements are, the fourth movement is something else. The likes of that choral finale, set to Schiller’s Ode to Joy, had never been heard before. Who could have conceived of an entire movement lasting longer than many complete symphonies, with chorus and vocal soloists to boot? Who could have imagined such an intricate conflation of styles?

The finale opens with a wild, earth-shaking dissonant chord and a passage of frenetic eighth notes that is answered by a recitative-like line in the lower strings. There’s a reprise of the first tempestuous line, then another recitative. This is when something magical happens. Above the shimmering tremolos of the cellos and second violins, the first violins play a familiar phrase: it’s the same descending figure that opens the symphony. But just when we think that Beethoven is employing some cyclical technique, he interrupts that phrase with another recitative. Ten bars later, we hear another quotation from earlier in the symphony—a bit of the Scherzo played by the woodwinds. It too ends mid-phrase, arrested before really getting started, and is followed by a recitative. This pattern continues with two glorious bars from the Adagio, before that music is also rudely interrupted and quickly dispensed with. It’s as if by summoning up, in turn, each of the previous movements, Beethoven is saying, Yes, these things are nostalgic and good, but they are of the past, and what I am now about to say is decidedly of the future. And so, we hear the movement’s famous theme—simple, quiet, unadorned—which will later be sung by the full heft of the chorus, Schiller’s words giving the music an added dimension of nobility, making it the anthem of universal brotherhood that we know so well.

Without Beethoven’s Ninth, it would be hard to imagine Liszt, Mahler, or Bruckner developing symphonic music in the way they did, exploring ever stranger realms of sound and sense. But what future course was laid out by On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? Alas, George Lazenby decided, soon after the movie was released, that he didn’t want anything more to do with Bond. In the next film in the series, Diamonds Are Forever, the producers hired Sean Connery again.